英特尔与微软的差距为何越来越大?

那是在2006年,作为全球计算机芯片领域的领导者,英特尔凭借在需求最高的个人电脑芯片和数据中心芯片领域的主导地位,营收和利润双双创下历史纪录。乔布斯希望英特尔为当时还没有问世的一款产品,也就是后来的iPhone手机,生产一种不同类型的芯片。

欧德宁知道,手机和平板设备的芯片将成为下一个热门领域,但英特尔必须把大量资本和最优秀的人才,投入到公司现有的利润丰厚的业务。此外,他在七年后对《大西洋》表示:“没有人知道iPhone会有什么影响。他们对一款芯片感兴趣,希望为它支付特定的价格,但不愿意多支付一美元。这个价格低于我们的预期成本。我无法接受。”他在不久之后卸任CEO。

欧德宁在2017年去世。从许多方面来看,他都是一位非常成功的CEO。但如果英特尔做了相反的决定,它可能已经成为后PC世代的芯片业巨头。它曾尝试成为一个重要的市场参与者,但却亏损了数十亿美元,于是2016年,英特尔放弃了手机芯片业务。欧德宁在离开公司时,似乎意识到他的决定的重要影响:“如果我们接受了苹果的要求,世界将会变得截然不同。”

与此同时,在英特尔以北约800英里的西雅图,微软在互联网、移动设备、社交媒体和搜索主导的科技领域,正在努力寻找自己的定位。它的努力并没有打动投资者。没有人能够预见,几年后,微软做出的几个关键决策,让公司变成了人工智能领域的巨头,并使股价暴涨。

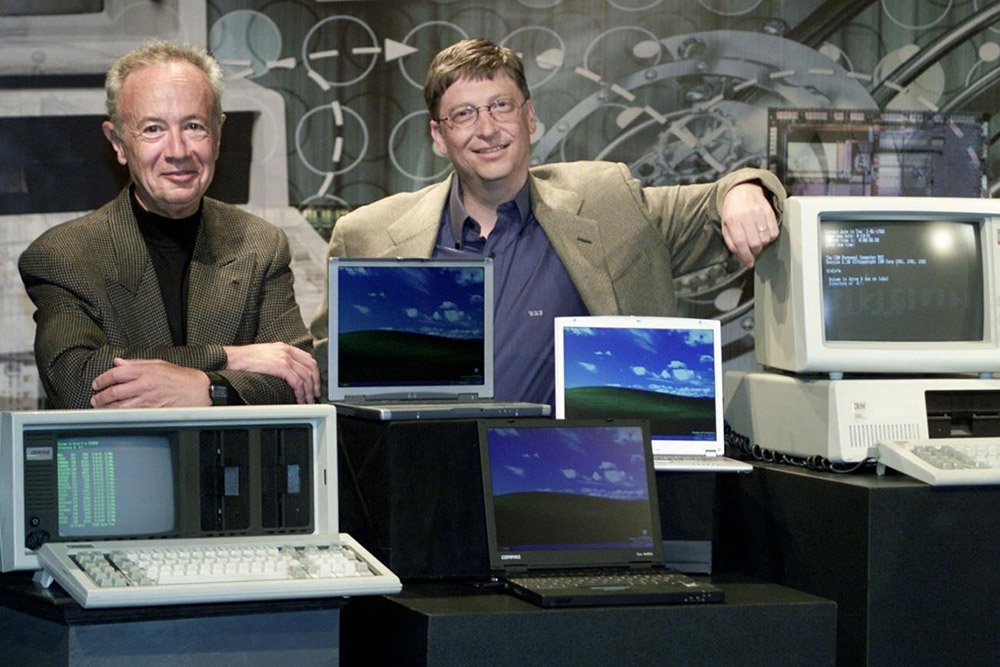

不久之前,微软和英特尔曾经雄霸科技界。它们彼此既不是竞争对手,也不是重要客户,但纽约大学(New York University)的亚当·布兰登伯格和耶鲁大学(Yale)的巴里·纳莱巴夫认为两家公司是“互补的”。多年来,微软凭借在使用英特尔芯片的电脑上运行的Windows操作系统赚得盆满钵满,而英特尔则设计运行Windows系统的新芯片(因此,它们组成了所谓的“Wintel”)。两家公司的联盟,促进了20世纪90年代领先的科技产品个人电脑的蓬勃发展。微软的比尔·盖茨成为一名著名的书呆子亿万富翁,而英特尔CEO安迪·格罗夫被《时代》杂志评为1997年年度人物。

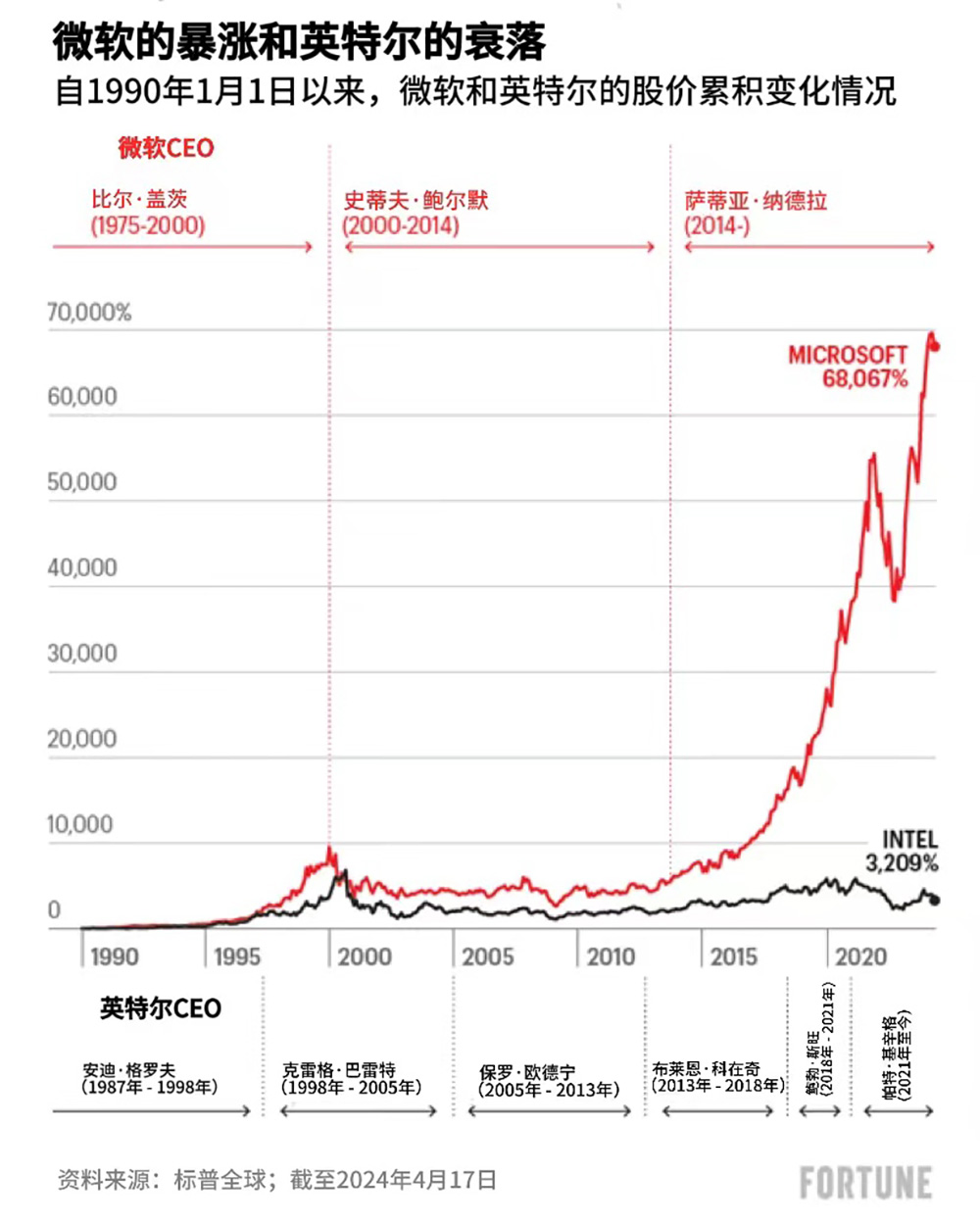

但后来两家公司的发展方向却大相径庭。2000年,微软是全世界最有价值的公司,而且在失去这个称号多年之后,微软现在已重回巅峰。2000年,英特尔的市值排在全球第6位,而且是全球最大的半导体厂商;现在其市值排在第69位,在半导体行业营收排在第2位,远远落后于排在首位的台积电(TSMC)(在某些年份还落后于三星(Samsung))。

一位《财富》500强公司的CEO,在职业生涯中要做出数千个决策,其中有些决策会产生重大影响。有些事情在事后很容易解释,比如微软成为人工智能领域的先驱,谷歌(Google)变成庞然大物,影碟租赁公司Blockbuster销声匿迹,但这些事情并非上天的安排。决定命运的决策往往在事后才会被确定。微软和英特尔的故事就是最好的佐证。这两家巨头公司成功和失败的研究案例,不仅为谷歌、OpenAI、亚马逊(Amazon)等目前领先的公司提供了商业战略的典范,也为希望在未来十年生存并繁荣发展的《财富》500强公司领导者提供了一堂商业战略大师课。

Wintel的起源

这两家公司的创办时间仅相隔了七年。英特尔创建于1968年,创始人包括计算机芯片的共同发明者罗伯特·诺伊斯和戈登·摩尔。摩尔在一篇开创性的文章中预言,芯片上的晶体管数量每年会翻一番,后来修正为每两年翻一番,这就是后人所说的“摩尔定律”。安迪·格罗夫是英特尔的三号员工。这三人至今仍被视为行业巨头。

众所周知,比尔·盖茨从哈佛大学(Harvard)肄业后,与童年好友保罗·艾伦共同创立了微软。他们对为个人计算机(也被称为微型计算机)这个新概念开发软件的前景感到兴奋。他们在1975年创建了微软。

1980年,IBM决定生产一款PC,为了迅速推进,决定使用其他公司开发的现有芯片和现有操作系统,于是这两家公司的发展道路交织在一起。IBM选择了英特尔的芯片和微软的操作系统,这深刻改变了这两家公司和公司的经营者。IBM的规模和声誉使其设计成为行业标准,因此后来几十年,无论哪家厂商的PC,全部都使用了英特尔的芯片和微软的操作系统。随着PC席卷美国和全球,英特尔和微软成了科技胜利、魅力、成功和1982年至2000年历史性牛市的象征。

后来,一切都发生了改变。

盖茨和格罗夫的“统治”结束

2000年10月,《财富》杂志发表了一篇文章,文章的插图将盖茨和格罗夫描绘成埃及不朽的狮身人面像。文章标题是《他们的统治结束了》。

文章解释道:“盖茨和格罗夫抓住了计算机架构中的两个关键节点——操作系统和PC微处理器,从而获得了霸权地位。但在由通用互联网协议连接起来的更多样化的新IT世界,没有这种明显的关键节点可以抢占。”

因此,这两家公司开始了长达数年的身份危机。英特尔的PC芯片和微软的PC操作系统和应用程序仍然是利润丰厚的业务,但这两家公司及其投资者都知道这并非未来之路。未来到底是什么?谁将引领新时代?

2000年1月,盖茨在担任CEO 25年后卸任,由微软总裁、盖茨的大学好友史蒂夫·鲍尔默接任;盖茨仍任董事长。两天后,微软股价暴跌。当天,微软的市值为6,190亿美元,在之后的近18年它都没有再达到这个水平。

2000年时,格罗夫已不再担任英特尔CEO,该职位在1998年就已经由长期担任公司高管的克雷格·巴雷特接任。但作为英特尔富有远见卓识和最成功的CEO,格罗夫仍担任董事会主席,发挥着重要作用。他的健康状况成了问题;1995年,他被诊断出患有前列腺癌,2000年又被诊断出患有帕金森氏病。英特尔的股价一路飙升,直到8月,公司市值达到5,000亿美元的最高峰。从那以后,公司股价再也没能重回巅峰。

最重要的是,2000年的互联网似乎开始让Wintel变得无关紧要。

在英特尔,巴雷特进行了一系列收购,其中许多收购对象来自电信和无线技术领域。在概念上,这是明智之举。手机正在走向主流,需要新型芯片。哈佛商学院(Harvard Business School)教授、时任英特尔董事会成员的大卫·约菲表示:“克雷格试图通过收购新业务,大力推动英特尔业务多元化。但我想说那并不是他的专长,这些收购都以失败告终。我们花费了120亿美元,结果回报为零或负数。”

在互联网泡沫破灭后的萧条时期,巴雷特继续投入数十亿美元新建芯片工厂(即晶圆厂)和开发新生产技术,以便在需求反弹时英特尔能够占据有利地位。这就引出了在Wintel的传奇历程背后最重要的经验教训之一:即使在转型时期,公司几乎也会不由自主地保护现有业务。这样做通常听起来很合理,但却存在让公司未来陷入困境的危险。正如伟大的管理作家彼得·德鲁克所说:“如果领导者无法摆脱昨天,放弃昨天,他们就无法创造明天。”

“我们搞砸了”

2005年至2010年担任微软高管的雷·奥兹表示,在2000年代的微软,“关于PC的形状和体积、操作系统的利润率,以及Word或Excel等应用程序未来会发生哪些变化,情况并不明朗。未来PC将会消亡,还是会继续增长和蓬勃发展,微软内部以及整个行业都就此展开了激烈讨论。”也许Word、Excel和那些安装在硬盘上的其他应用程序,会迁移到互联网上,类似于2006年初推出的Google Docs。在这种情况下,微软需要一种新的商业模式。微软应该开发一个新商业模式吗?一些高管这样认为。但没有人知道确切答案。

在这段时期,微软不再是企业创新的典范,而是陷入了成功的公司被颠覆时经常会发生的状况。奥兹解释道:“当你拥有丰富的资源且面临多个生存威胁时,保护公司最自然的做法就是采取并行发展策略。更加困难的是坚持己见做出选择,并全力以赴。不幸的是,采取并行发展策略会在各个部门之间造成隔阂和内部冲突,这会导致公司经营失灵。”

随着团队之间相互争抢主导地位,微软错过了自PC时代以来最赚钱的两个业务:搜索和手机。这些失误并不致命,因为微软仍然拥有两个可靠且高利润的业务:Windows操作系统和Office系列应用程序。但用德鲁克的话来说,这些都是过时的业务。投资者没有看到实质性的未来业务,这就是为什么多年来微软的股价持续低迷。错失搜索和手机业务并未威胁到微软的生存,却影响到微软在日新月异的新时代的相关性和重要性,这最终可能损害公司在投资者和全球最优秀员工中的吸引力。这些关键失误背后的原因很有教育意义。

2000年,谷歌还是一家名不见经传的互联网搜索初创公司,没有明确的商业模式,但它有一种大致的理念,认为卖广告有利可图。最后的结果人尽皆知:谷歌在2023年的广告收入高达2,380亿美元。这对于微软而言是一种完全陌生的模式,微软的收入依赖的是开发和高价出售软件。向用户免费?卖广告?微软从来没有经营过与谷歌类似的业务。当谷歌的模式得到验证时,微软已经远远落后。据网络流量分析公司StatCounter称,如今微软的必应(Bing)搜索引擎在全球各平台上的市场份额仅为3%。而谷歌的市场份额为92%。

微软在手机领域也遭遇了基本类似的失败,等到微软完全理解了手机业务的结构已经为时已晚。微软以为手机行业的发展会与PC行业类似,就像戴尔(Dell)等PC销售商用英特尔的芯片和微软的软件组合成最终产品一样。但是苹果与众不同的iPhone商业模式大获成功,苹果自己设计芯片并编写软件。手机行业的另一大赢家是谷歌的安卓智能手机操作系统,它同样无视了PC模式。谷歌并不出售操作系统,而是将其免费提供给三星、摩托罗拉(Motorola)等手机制造商。谷歌的收入来自在每部手机上安装其搜索引擎,并在用户购买应用时,向应用开发者收取一笔费用。

比尔·盖茨承认,微软在手机领域的失误改变了公司的命运。他在2020年回顾自己的职业生涯时表示:“这是我在明显在我们技能范围以内的事情上犯下的最大错误。”

英特尔同样以类似的方式,错失了手机行业的巨大商机。它无法适应变化。英特尔意识到手机行业的机会,早在2000年代初,就为备受欢迎的黑莓(BlackBerry)手机供应芯片。问题是,这些芯片的设计者并非英特尔,而是英国公司Arm。Arm设计芯片,但并不生产芯片。Arm设计的一种芯片架构,功耗低于其他芯片,这对于手机至关重要。英特尔负责生产芯片,并向Arm支付专利费。

英特尔更愿意使用自己的x86架构生产手机芯片,这可以理解。保罗·欧德宁决定停止生产Arm芯片,并为手机开发一款x86芯片——约菲认为,事后来看,“这是一个重大战略错误”。他回忆道:“当时的计划是,我们将在一年内开发出一款竞争产品,结果十年过去了也没有实现这个计划。并不是我们错过了手机带来的机遇,而是我们搞砸了。”

探索巨大潮流

2000年是英特尔和微软的转折点,2013年也是如此。广义上说,它们陷入了同样的困境:曾令它们伟大的业务仍在给公司创造收入;它们想要参与下一个大机遇却为时已晚或不成功;它们都在努力寻找下一个可以主导的巨大潮流。它们的股价在至少十年内或多或少陷入低迷。2013年5月,保罗·欧德宁不再担任英特尔CEO。8月,史蒂夫·鲍尔默宣布将辞去微软CEO的职务。

接班计划是董事会的头等大事,这比起董事会的其他所有任务加起来都更为重要。这其中总是会存在较高的风险。英特尔和微软董事会相隔9个月处理公司接班人问题的方式,在很大程度上可以解释为什么两家公司会戏剧性地走上不同发展道路。

在欧德宁的接班人布赖恩·科在奇的领导下,英特尔始终无法按时交付新芯片——讽刺的是,英特尔甚至无法像竞争对手一样,跟上摩尔定律,而且公司的市场份额萎缩。该公司放弃了智能手机芯片。一项调查发现科在奇与一名员工有过两厢情愿的亲密关系,于是担任了五年CEO的科在奇突然辞职。首席财务官鲍勃·斯旺接任CEO,而生产问题持续到2021年,英特尔在其历史上首次面临其芯片比竞争对手落后两代的窘境。这些竞争对手是中国台湾的台积电(TSMC)和韩国的三星。

在危机中,英特尔董事会召回了从公司离职11年的工程师帕特·基辛格。基辛格曾在公司工作了30年,辞职后曾担任EMC的高管,后来成为VMware首席执行官。作为英特尔的CEO,基辛格宣布了一个雄心勃勃且成本高昂的计划,旨在夺回公司在芯片技术领域的世界领导地位。

微软董事会花了近六个月时间,在全球范围内寻找鲍尔默的继任者。外界公开讨论的候选人至少有17人。英国和拉斯维加斯的博彩商对最终的胜出者开出了赔率;最近担任CEO满十年的萨提亚·纳德拉,当时的赔率是14赔1,并不被看好。

纳德拉可以说是多年来乃至数十年来,各行各业最好的公司接班人选择。在他的领导下,微软股价最终突破了14年的交易区间并大幅上涨,涨幅超过1,000%。微软再次成为全球市值最高的公司,最近的市值高达3.1万亿美元。基辛格担任英特尔CEO刚满三年,因此还无法全面评价;业内专家们都在猜测他是否能成为英特尔的纳德拉。但这两位CEO都为公司如何走出过去、迈向未来,提供了有用范例。

纳德拉以外来者的视角审视公司,推动公司转型,在没有引起太大轰动的情况下进行大刀阔斧的改革。他首先让Office应用程序(Word,Excel)与苹果的iPhone和iPad兼容——这在微软看来是异端邪说,因为微软把苹果视为主要敌人。但纳德拉意识到,这两家公司之间没有太多竞争,为什么不让更多人依赖Office应用程序呢?这一举措向公司和全世界传递了一个信息:微软文化中根深蒂固的傲慢将大为减少。现在微软可以接受与其他公司实现互操作。

这对微软而言是一种全新的商业模式,未来还会有更多新的模式出现。例如,纳德拉收购了LinkedIn,LinkedIn在微软已经彻底错过的社交媒体领域占有一席之地。然后,微软又收购了曾不屑一顾的开源代码库GitHub。这两笔交易以及其他几笔交易都大获成功。

总的来说,纳德拉为新环境带来了一种全新的领导风格。在一家以恶意内斗而著称的公司,可能因为内讧让行动陷入瘫痪,但他却解决了长期以来围绕重大项目的辩论。例如,2016年,他出售了微软在他成为CEO前一年收购的诺基亚(Nokia)手机业务,承认公司已经输掉了手机战。一位前高管表示:“人们不太理解为什么微软在萨蒂亚的领导下能够一片欣欣向荣。他的超能力在于做出选择,消除冲突,让业务蓬勃发展。”

在英特尔,基辛格也掀起了挑战公司文化的改革。该公司凭借设计尖端芯片和具备行业领先的制造技术而树立了行业主导地位。带着这种强烈的自豪感,单独创建一家代工厂,生产他人设计的芯片,被视为大逆不道。然而,在基辛格的领导下,英特尔创立了新代工业务,同时更多地依赖其他代工厂生产自己的芯片,包括全球最大的芯片制造商台积电——这对公司文化来说是双重冲击。

让一家有悠久文化传统的老牌公司,像纳德拉和基辛格一样接受貌似很陌生的商业模式,可能是一个痛苦的艰难过程。通常只有新CEO才能带来开放的心态,实现这种转变。当一家公司需要更新其企业战略时,也会出现同样的问题。微软多年来一直在寻找和讨论下一个热门领域,但纳德拉认为公司没有必要去寻找一个可能潜力巨大的、面向未来的新业务。它已经有了一个这样的业务:云计算服务Azure。Amazon Web Services无论过去还是现在都业内领先,但Azure已经成为势头强劲的第二名,因为纳德拉为该业务投入了充足的资本和一些公司最聪明的员工。他还在ChatGPT的开发者OpenAI进行了一笔非同寻常的投资,早在该公司名声大噪之前就承诺向其投资130亿美元。现在Azure向其客户提供OpenAI的技术。按照德鲁克的说法,这就是一项蓬勃发展的未来业务。

基辛格对英特尔战略的改革更加激进。他大胆利用美国政府的数十亿美元,并大获成功。通过《芯片与科学法案》(CHIPS and Science Act),英特尔可以获得多达440亿美元的援助,用于未来几年在美国新建芯片工厂。他对《财富》杂志表示:“我喜欢开玩笑地说,为了推动《芯片法案》,没有人比我投入的精力更多。我见过大量参议员、众议员和各州的政治团体。我为了它付出了很多努力。”

一个关键的观点是,对于微软和英特尔这种有过成功经历的大公司,要摆脱过时的战略并全面拥抱新战略难度巨大,有时候甚至是不可能的。多年来,这两家公司一直在尝试却未能成功。还有一个相关的观点是:对于纳德拉和基辛格来说,这样做更容易,因为他们具有“内部外来”领导者的优势,对公司有深刻了解,但没有深度参与公司的战略。纳德拉在成为CEO之前长期从事Azure工作,而不是Windows操作系统或Office应用程序,而基辛格曾离开英特尔11年,这让他有机会重新思考一切。

一个更重要的教训是,在这两家伟大公司的发展历程中,接班计划是最重要的因素。过去24年,微软的整体表现优于英特尔,在此期间,微软只有两位CEO,而英特尔却经历了多达5位CEO。大多数人在解释一家公司的业绩时会研究CEO,但他们首先应该研究的是选择CEO的人,也就是公司的董事会。

回顾这些故事,我们禁不住会问“如果……会怎么样”这样的问题。如果保罗·欧德宁同意了史蒂夫·乔布斯的要求会怎么样?如果英特尔或微软的任何一位CEO另有其人会怎么样?如果在另一位CEO的领导下,英特尔开发出一款成功的GPU,也就是如今驱动人工智能引擎的芯片(它曾进行过尝试)——你还会听说过英伟达(Nvidia)吗?比尔·盖茨在2019年表示:“我们差一点点就成为主流手机操作系统。”如果这一点点稍微发生了偏移会怎么样?你今天会用哪个品牌的手机?

这些问题会令人陶醉其中无法自拔,当然不会有任何答案。回顾历史和思考这些假设问题的价值在于,提醒我们领导者每天都在创造未来,如果他们不能从历史中总结经验教训,那就是失职。

Wintel研究案例的五个启示

1. 成功可能是一家公司最大的敌人。伟大的管理作家彼得·德鲁克曾说过,每家公司必须“抛弃昨天”,才能“创造明天”。但在一家成功的公司中,领导者会不由自主地保护“昨天”。英特尔和微软为创造明天努力了多年。

2. 领导者必须愿意接受貌似奇怪的商业模式。无论是免费提供软件还是将生产他人设计的芯片作为一项独立业务,微软和英特尔都在改变经营策略,应对竞争对手。

3. 统一思想。辩论在一定程度上是健康的,但在微软,辩论持续了太长时间,直到纳德拉成为CEO并明确了优先事项才结束。在英特尔,接连更换的CEO们支持不同解决方案来应对其业务下滑的问题,这导致公司长期处于战略混乱的状态。

4. 接班计划是董事会的头等大事,这比起董事会的其他所有任务加起来都更为重要。每个人都知道这一点,但一些董事会依旧没有做好这项工作。如果他们犯了错,其他所有教训都无关紧要。过去24年,微软的整体表现优于英特尔,在此期间,微软只有两位CEO,而英特尔却经历了多达5位CEO。

5. 失败不会致命。Wintel的故事提醒我们,所有公司,包括最优秀的公司,都会遭遇失败并陷入危机。没有公司能够幸免。任何公司的领导者,甚至是最杰出的公司,都必须时刻准备运用组织救援技能,并且知道这也是一家伟大公司的一部分。(财富中文网)

译者:刘进龙

审校:汪皓

史蒂夫·乔布斯不喜欢听到别人说“不”。但英特尔(Intel)CEO保罗·欧德宁就曾这样回复乔布斯。

那是在2006年,作为全球计算机芯片领域的领导者,英特尔凭借在需求最高的个人电脑芯片和数据中心芯片领域的主导地位,营收和利润双双创下历史纪录。乔布斯希望英特尔为当时还没有问世的一款产品,也就是后来的iPhone手机,生产一种不同类型的芯片。

欧德宁知道,手机和平板设备的芯片将成为下一个热门领域,但英特尔必须把大量资本和最优秀的人才,投入到公司现有的利润丰厚的业务。此外,他在七年后对《大西洋》表示:“没有人知道iPhone会有什么影响。他们对一款芯片感兴趣,希望为它支付特定的价格,但不愿意多支付一美元。这个价格低于我们的预期成本。我无法接受。”他在不久之后卸任CEO。

欧德宁在2017年去世。从许多方面来看,他都是一位非常成功的CEO。但如果英特尔做了相反的决定,它可能已经成为后PC世代的芯片业巨头。它曾尝试成为一个重要的市场参与者,但却亏损了数十亿美元,于是2016年,英特尔放弃了手机芯片业务。欧德宁在离开公司时,似乎意识到他的决定的重要影响:“如果我们接受了苹果的要求,世界将会变得截然不同。”

1981年推出的IBM电脑,让英特尔的芯片和微软(Microsoft)的软件,走进了全世界的家庭和企业。

与此同时,在英特尔以北约800英里的西雅图,微软在互联网、移动设备、社交媒体和搜索主导的科技领域,正在努力寻找自己的定位。它的努力并没有打动投资者。没有人能够预见,几年后,微软做出的几个关键决策,让公司变成了人工智能领域的巨头,并使股价暴涨。

不久之前,微软和英特尔曾经雄霸科技界。它们彼此既不是竞争对手,也不是重要客户,但纽约大学(New York University)的亚当·布兰登伯格和耶鲁大学(Yale)的巴里·纳莱巴夫认为两家公司是“互补的”。多年来,微软凭借在使用英特尔芯片的电脑上运行的Windows操作系统赚得盆满钵满,而英特尔则设计运行Windows系统的新芯片(因此,它们组成了所谓的“Wintel”)。两家公司的联盟,促进了20世纪90年代领先的科技产品个人电脑的蓬勃发展。微软的比尔·盖茨成为一名著名的书呆子亿万富翁,而英特尔CEO安迪·格罗夫被《时代》杂志评为1997年年度人物。

但后来两家公司的发展方向却大相径庭。2000年,微软是全世界最有价值的公司,而且在失去这个称号多年之后,微软现在已重回巅峰。2000年,英特尔的市值排在全球第6位,而且是全球最大的半导体厂商;现在其市值排在第69位,在半导体行业营收排在第2位,远远落后于排在首位的台积电(TSMC)(在某些年份还落后于三星(Samsung))。

这两家科技巨头的股票曾一度有类似的走势,直到微软开始进行大胆的尝试。

一位《财富》500强公司的CEO,在职业生涯中要做出数千个决策,其中有些决策会产生重大影响。有些事情在事后很容易解释,比如微软成为人工智能领域的先驱,谷歌(Google)变成庞然大物,影碟租赁公司Blockbuster销声匿迹,但这些事情并非上天的安排。决定命运的决策往往在事后才会被确定。微软和英特尔的故事就是最好的佐证。这两家巨头公司成功和失败的研究案例,不仅为谷歌、OpenAI、亚马逊(Amazon)等目前领先的公司提供了商业战略的典范,也为希望在未来十年生存并繁荣发展的《财富》500强公司领导者提供了一堂商业战略大师课。

Wintel的起源

这两家公司的创办时间仅相隔了七年。英特尔创建于1968年,创始人包括计算机芯片的共同发明者罗伯特·诺伊斯和戈登·摩尔。摩尔在一篇开创性的文章中预言,芯片上的晶体管数量每年会翻一番,后来修正为每两年翻一番,这就是后人所说的“摩尔定律”。安迪·格罗夫是英特尔的三号员工。这三人至今仍被视为行业巨头。

众所周知,比尔·盖茨从哈佛大学(Harvard)肄业后,与童年好友保罗·艾伦共同创立了微软。他们对为个人计算机(也被称为微型计算机)这个新概念开发软件的前景感到兴奋。他们在1975年创建了微软。

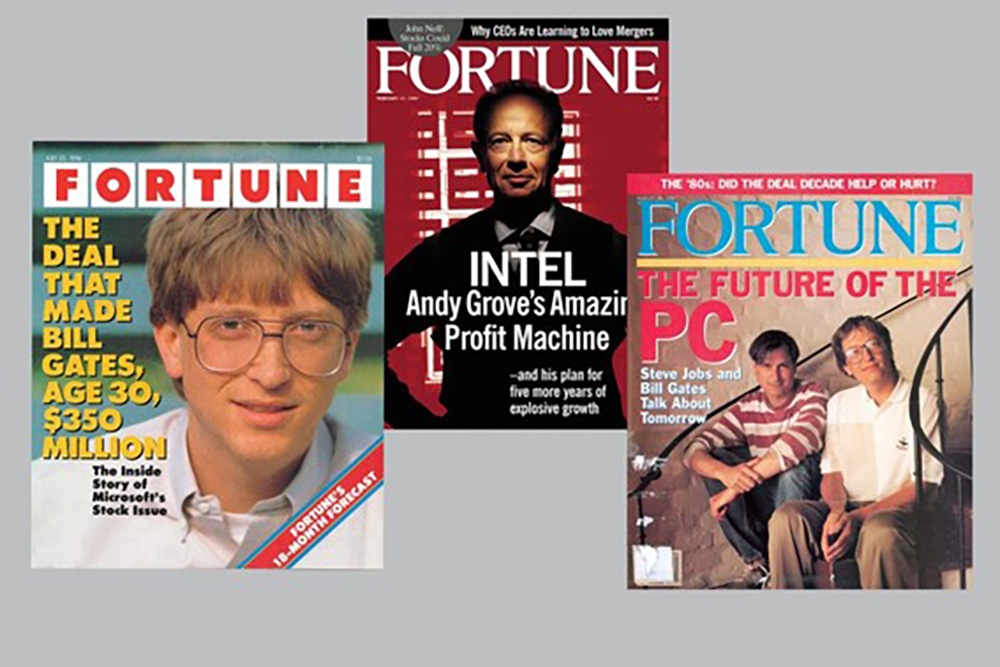

过去数十年,《财富》杂志封面上的盖茨和格罗夫。

1980年,IBM决定生产一款PC,为了迅速推进,决定使用其他公司开发的现有芯片和现有操作系统,于是这两家公司的发展道路交织在一起。IBM选择了英特尔的芯片和微软的操作系统,这深刻改变了这两家公司和公司的经营者。IBM的规模和声誉使其设计成为行业标准,因此后来几十年,无论哪家厂商的PC,全部都使用了英特尔的芯片和微软的操作系统。随着PC席卷美国和全球,英特尔和微软成了科技胜利、魅力、成功和1982年至2000年历史性牛市的象征。

后来,一切都发生了改变。

盖茨和格罗夫的“统治”结束

2000年10月,《财富》杂志发表了一篇文章,文章的插图将盖茨和格罗夫描绘成埃及不朽的狮身人面像。文章标题是《他们的统治结束了》。

文章解释道:“盖茨和格罗夫抓住了计算机架构中的两个关键节点——操作系统和PC微处理器,从而获得了霸权地位。但在由通用互联网协议连接起来的更多样化的新IT世界,没有这种明显的关键节点可以抢占。”

因此,这两家公司开始了长达数年的身份危机。英特尔的PC芯片和微软的PC操作系统和应用程序仍然是利润丰厚的业务,但这两家公司及其投资者都知道这并非未来之路。未来到底是什么?谁将引领新时代?

2000年1月,盖茨在担任CEO 25年后卸任,由微软总裁、盖茨的大学好友史蒂夫·鲍尔默接任;盖茨仍任董事长。两天后,微软股价暴跌。当天,微软的市值为6,190亿美元,在之后的近18年它都没有再达到这个水平。

2000年时,格罗夫已不再担任英特尔CEO,该职位在1998年就已经由长期担任公司高管的克雷格·巴雷特接任。但作为英特尔富有远见卓识和最成功的CEO,格罗夫仍担任董事会主席,发挥着重要作用。他的健康状况成了问题;1995年,他被诊断出患有前列腺癌,2000年又被诊断出患有帕金森氏病。英特尔的股价一路飙升,直到8月,公司市值达到5,000亿美元的最高峰。从那以后,公司股价再也没能重回巅峰。

最重要的是,2000年的互联网似乎开始让Wintel变得无关紧要。

在英特尔,巴雷特进行了一系列收购,其中许多收购对象来自电信和无线技术领域。在概念上,这是明智之举。手机正在走向主流,需要新型芯片。哈佛商学院(Harvard Business School)教授、时任英特尔董事会成员的大卫·约菲表示:“克雷格试图通过收购新业务,大力推动英特尔业务多元化。但我想说那并不是他的专长,这些收购都以失败告终。我们花费了120亿美元,结果回报为零或负数。”

在互联网泡沫破灭后的萧条时期,巴雷特继续投入数十亿美元新建芯片工厂(即晶圆厂)和开发新生产技术,以便在需求反弹时英特尔能够占据有利地位。这就引出了在Wintel的传奇历程背后最重要的经验教训之一:即使在转型时期,公司几乎也会不由自主地保护现有业务。这样做通常听起来很合理,但却存在让公司未来陷入困境的危险。正如伟大的管理作家彼得·德鲁克所说:“如果领导者无法摆脱昨天,放弃昨天,他们就无法创造明天。”

“我们搞砸了”

2005年至2010年担任微软高管的雷·奥兹表示,在2000年代的微软,“关于PC的形状和体积、操作系统的利润率,以及Word或Excel等应用程序未来会发生哪些变化,情况并不明朗。未来PC将会消亡,还是会继续增长和蓬勃发展,微软内部以及整个行业都就此展开了激烈讨论。”也许Word、Excel和那些安装在硬盘上的其他应用程序,会迁移到互联网上,类似于2006年初推出的Google Docs。在这种情况下,微软需要一种新的商业模式。微软应该开发一个新商业模式吗?一些高管这样认为。但没有人知道确切答案。

在这段时期,微软不再是企业创新的典范,而是陷入了成功的公司被颠覆时经常会发生的状况。奥兹解释道:“当你拥有丰富的资源且面临多个生存威胁时,保护公司最自然的做法就是采取并行发展策略。更加困难的是坚持己见做出选择,并全力以赴。不幸的是,采取并行发展策略会在各个部门之间造成隔阂和内部冲突,这会导致公司经营失灵。”

随着团队之间相互争抢主导地位,微软错过了自PC时代以来最赚钱的两个业务:搜索和手机。这些失误并不致命,因为微软仍然拥有两个可靠且高利润的业务:Windows操作系统和Office系列应用程序。但用德鲁克的话来说,这些都是过时的业务。投资者没有看到实质性的未来业务,这就是为什么多年来微软的股价持续低迷。错失搜索和手机业务并未威胁到微软的生存,却影响到微软在日新月异的新时代的相关性和重要性,这最终可能损害公司在投资者和全球最优秀员工中的吸引力。这些关键失误背后的原因很有教育意义。

2000年,谷歌还是一家名不见经传的互联网搜索初创公司,没有明确的商业模式,但它有一种大致的理念,认为卖广告有利可图。最后的结果人尽皆知:谷歌在2023年的广告收入高达2,380亿美元。这对于微软而言是一种完全陌生的模式,微软的收入依赖的是开发和高价出售软件。向用户免费?卖广告?微软从来没有经营过与谷歌类似的业务。当谷歌的模式得到验证时,微软已经远远落后。据网络流量分析公司StatCounter称,如今微软的必应(Bing)搜索引擎在全球各平台上的市场份额仅为3%。而谷歌的市场份额为92%。

谷歌创始人谢尔盖·布林(左)和拉里·佩奇让微软陷入了身份危机。

微软在手机领域也遭遇了基本类似的失败,等到微软完全理解了手机业务的结构已经为时已晚。微软以为手机行业的发展会与PC行业类似,就像戴尔(Dell)等PC销售商用英特尔的芯片和微软的软件组合成最终产品一样。但是苹果与众不同的iPhone商业模式大获成功,苹果自己设计芯片并编写软件。手机行业的另一大赢家是谷歌的安卓智能手机操作系统,它同样无视了PC模式。谷歌并不出售操作系统,而是将其免费提供给三星、摩托罗拉(Motorola)等手机制造商。谷歌的收入来自在每部手机上安装其搜索引擎,并在用户购买应用时,向应用开发者收取一笔费用。

比尔·盖茨承认,微软在手机领域的失误改变了公司的命运。他在2020年回顾自己的职业生涯时表示:“这是我在明显在我们技能范围以内的事情上犯下的最大错误。”

英特尔同样以类似的方式,错失了手机行业的巨大商机。它无法适应变化。英特尔意识到手机行业的机会,早在2000年代初,就为备受欢迎的黑莓(BlackBerry)手机供应芯片。问题是,这些芯片的设计者并非英特尔,而是英国公司Arm。Arm设计芯片,但并不生产芯片。Arm设计的一种芯片架构,功耗低于其他芯片,这对于手机至关重要。英特尔负责生产芯片,并向Arm支付专利费。

2006年,史蒂夫·乔布斯在莫斯克尼中心发表主题演讲,并宣布在Mac电脑中使用英特尔的处理器。右侧为英特尔CEO保罗·欧德宁。

英特尔更愿意使用自己的x86架构生产手机芯片,这可以理解。保罗·欧德宁决定停止生产Arm芯片,并为手机开发一款x86芯片——约菲认为,事后来看,“这是一个重大战略错误”。他回忆道:“当时的计划是,我们将在一年内开发出一款竞争产品,结果十年过去了也没有实现这个计划。并不是我们错过了手机带来的机遇,而是我们搞砸了。”

探索巨大潮流

2000年是英特尔和微软的转折点,2013年也是如此。广义上说,它们陷入了同样的困境:曾令它们伟大的业务仍在给公司创造收入;它们想要参与下一个大机遇却为时已晚或不成功;它们都在努力寻找下一个可以主导的巨大潮流。它们的股价在至少十年内或多或少陷入低迷。2013年5月,保罗·欧德宁不再担任英特尔CEO。8月,史蒂夫·鲍尔默宣布将辞去微软CEO的职务。

接班计划是董事会的头等大事,这比起董事会的其他所有任务加起来都更为重要。这其中总是会存在较高的风险。英特尔和微软董事会相隔9个月处理公司接班人问题的方式,在很大程度上可以解释为什么两家公司会戏剧性地走上不同发展道路。

在欧德宁的接班人布赖恩·科在奇的领导下,英特尔始终无法按时交付新芯片——讽刺的是,英特尔甚至无法像竞争对手一样,跟上摩尔定律,而且公司的市场份额萎缩。该公司放弃了智能手机芯片。一项调查发现科在奇与一名员工有过两厢情愿的亲密关系,于是担任了五年CEO的科在奇突然辞职。首席财务官鲍勃·斯旺接任CEO,而生产问题持续到2021年,英特尔在其历史上首次面临其芯片比竞争对手落后两代的窘境。这些竞争对手是中国台湾的台积电(TSMC)和韩国的三星。

在危机中,英特尔董事会召回了从公司离职11年的工程师帕特·基辛格。基辛格曾在公司工作了30年,辞职后曾担任EMC的高管,后来成为VMware首席执行官。作为英特尔的CEO,基辛格宣布了一个雄心勃勃且成本高昂的计划,旨在夺回公司在芯片技术领域的世界领导地位。

微软董事会花了近六个月时间,在全球范围内寻找鲍尔默的继任者。外界公开讨论的候选人至少有17人。英国和拉斯维加斯的博彩商对最终的胜出者开出了赔率;最近担任CEO满十年的萨提亚·纳德拉,当时的赔率是14赔1,并不被看好。

纳德拉可以说是多年来乃至数十年来,各行各业最好的公司接班人选择。在他的领导下,微软股价最终突破了14年的交易区间并大幅上涨,涨幅超过1,000%。微软再次成为全球市值最高的公司,最近的市值高达3.1万亿美元。基辛格担任英特尔CEO刚满三年,因此还无法全面评价;业内专家们都在猜测他是否能成为英特尔的纳德拉。但这两位CEO都为公司如何走出过去、迈向未来,提供了有用范例。

纳德拉以外来者的视角审视公司,推动公司转型,在没有引起太大轰动的情况下进行大刀阔斧的改革。他首先让Office应用程序(Word,Excel)与苹果的iPhone和iPad兼容——这在微软看来是异端邪说,因为微软把苹果视为主要敌人。但纳德拉意识到,这两家公司之间没有太多竞争,为什么不让更多人依赖Office应用程序呢?这一举措向公司和全世界传递了一个信息:微软文化中根深蒂固的傲慢将大为减少。现在微软可以接受与其他公司实现互操作。

这对微软而言是一种全新的商业模式,未来还会有更多新的模式出现。例如,纳德拉收购了LinkedIn,LinkedIn在微软已经彻底错过的社交媒体领域占有一席之地。然后,微软又收购了曾不屑一顾的开源代码库GitHub。这两笔交易以及其他几笔交易都大获成功。

总的来说,纳德拉为新环境带来了一种全新的领导风格。在一家以恶意内斗而著称的公司,可能因为内讧让行动陷入瘫痪,但他却解决了长期以来围绕重大项目的辩论。例如,2016年,他出售了微软在他成为CEO前一年收购的诺基亚(Nokia)手机业务,承认公司已经输掉了手机战。一位前高管表示:“人们不太理解为什么微软在萨蒂亚的领导下能够一片欣欣向荣。他的超能力在于做出选择,消除冲突,让业务蓬勃发展。”

在英特尔,基辛格也掀起了挑战公司文化的改革。该公司凭借设计尖端芯片和具备行业领先的制造技术而树立了行业主导地位。带着这种强烈的自豪感,单独创建一家代工厂,生产他人设计的芯片,被视为大逆不道。然而,在基辛格的领导下,英特尔创立了新代工业务,同时更多地依赖其他代工厂生产自己的芯片,包括全球最大的芯片制造商台积电——这对公司文化来说是双重冲击。

让一家有悠久文化传统的老牌公司,像纳德拉和基辛格一样接受貌似很陌生的商业模式,可能是一个痛苦的艰难过程。通常只有新CEO才能带来开放的心态,实现这种转变。当一家公司需要更新其企业战略时,也会出现同样的问题。微软多年来一直在寻找和讨论下一个热门领域,但纳德拉认为公司没有必要去寻找一个可能潜力巨大的、面向未来的新业务。它已经有了一个这样的业务:云计算服务Azure。Amazon Web Services无论过去还是现在都业内领先,但Azure已经成为势头强劲的第二名,因为纳德拉为该业务投入了充足的资本和一些公司最聪明的员工。他还在ChatGPT的开发者OpenAI进行了一笔非同寻常的投资,早在该公司名声大噪之前就承诺向其投资130亿美元。现在Azure向其客户提供OpenAI的技术。按照德鲁克的说法,这就是一项蓬勃发展的未来业务。

基辛格对英特尔战略的改革更加激进。他大胆利用美国政府的数十亿美元,并大获成功。通过《芯片与科学法案》(CHIPS and Science Act),英特尔可以获得多达440亿美元的援助,用于未来几年在美国新建芯片工厂。他对《财富》杂志表示:“我喜欢开玩笑地说,为了推动《芯片法案》,没有人比我投入的精力更多。我见过大量参议员、众议员和各州的政治团体。我为了它付出了很多努力。”

一个关键的观点是,对于微软和英特尔这种有过成功经历的大公司,要摆脱过时的战略并全面拥抱新战略难度巨大,有时候甚至是不可能的。多年来,这两家公司一直在尝试却未能成功。还有一个相关的观点是:对于纳德拉和基辛格来说,这样做更容易,因为他们具有“内部外来”领导者的优势,对公司有深刻了解,但没有深度参与公司的战略。纳德拉在成为CEO之前长期从事Azure工作,而不是Windows操作系统或Office应用程序,而基辛格曾离开英特尔11年,这让他有机会重新思考一切。

一个更重要的教训是,在这两家伟大公司的发展历程中,接班计划是最重要的因素。过去24年,微软的整体表现优于英特尔,在此期间,微软只有两位CEO,而英特尔却经历了多达5位CEO。大多数人在解释一家公司的业绩时会研究CEO,但他们首先应该研究的是选择CEO的人,也就是公司的董事会。

回顾这些故事,我们禁不住会问“如果……会怎么样”这样的问题。如果保罗·欧德宁同意了史蒂夫·乔布斯的要求会怎么样?如果英特尔或微软的任何一位CEO另有其人会怎么样?如果在另一位CEO的领导下,英特尔开发出一款成功的GPU,也就是如今驱动人工智能引擎的芯片(它曾进行过尝试)——你还会听说过英伟达(Nvidia)吗?比尔·盖茨在2019年表示:“我们差一点点就成为主流手机操作系统。”如果这一点点稍微发生了偏移会怎么样?你今天会用哪个品牌的手机?

这些问题会令人陶醉其中无法自拔,当然不会有任何答案。回顾历史和思考这些假设问题的价值在于,提醒我们领导者每天都在创造未来,如果他们不能从历史中总结经验教训,那就是失职。

Wintel研究案例的五个启示

1. 成功可能是一家公司最大的敌人。伟大的管理作家彼得·德鲁克曾说过,每家公司必须“抛弃昨天”,才能“创造明天”。但在一家成功的公司中,领导者会不由自主地保护“昨天”。英特尔和微软为创造明天努力了多年。

2. 领导者必须愿意接受貌似奇怪的商业模式。无论是免费提供软件还是将生产他人设计的芯片作为一项独立业务,微软和英特尔都在改变经营策略,应对竞争对手。

3. 统一思想。辩论在一定程度上是健康的,但在微软,辩论持续了太长时间,直到纳德拉成为CEO并明确了优先事项才结束。在英特尔,接连更换的CEO们支持不同解决方案来应对其业务下滑的问题,这导致公司长期处于战略混乱的状态。

4. 接班计划是董事会的头等大事,这比起董事会的其他所有任务加起来都更为重要。每个人都知道这一点,但一些董事会依旧没有做好这项工作。如果他们犯了错,其他所有教训都无关紧要。过去24年,微软的整体表现优于英特尔,在此期间,微软只有两位CEO,而英特尔却经历了多达5位CEO。

5. 失败不会致命。Wintel的故事提醒我们,所有公司,包括最优秀的公司,都会遭遇失败并陷入危机。没有公司能够幸免。任何公司的领导者,甚至是最杰出的公司,都必须时刻准备运用组织救援技能,并且知道这也是一家伟大公司的一部分。(财富中文网)

译者:刘进龙

审校:汪皓

Bill Gates and Andy Grove saw their companies follow very different trajectories after they each stepped down.

REUTERS

Steve Jobs wasn’t accustomed to hearing “no.” But that was the answer from Paul Otellini, CEO of Intel.

It was 2006, and Intel, the global king of computer chips, was bringing in record revenue and profits by dominating the kinds of chips in hottest demand—for personal computers and data centers. Now Jobs wanted Intel to make a different type of chip for a product that didn’t even exist, which would be called the iPhone.

Otellini knew chips for phones and tablets were the next big thing, but Intel had to devote substantial capital and its best minds to the fabulously profitable business it already possessed. Besides, “no one knew what the iPhone would do,” he told The Atlantic seven years later, just before he stepped down as CEO. “There was a chip that they were interested in, that they wanted to pay a certain price for and not a nickel more, and that price was below our forecasted cost. I couldn’t see it.”

Otellini, who died in 2017, was a highly successful CEO by many measures. But if that decision had gone the other way, Intel might have become a chip titan of the post-PC era. Instead, it gave up on phone chips in 2016 after losing billions trying to become a significant player. As he left the company, Otellini seemed to grasp the magnitude of his decision: “The world would have been a lot different if we’d done it.”

The IBM computer, introduced in 1981, rocketed Intel’s chips and Microsoft’s software to households and businesses around the globe.

SSPL/GETTY IMAGES

Meantime, some 800 miles north, in Seattle, Microsoft was struggling to find its role in a tech world dominated by the internet, mobile devices, social media, and search. Investors were not impressed by its efforts. No one could have foreseen that years later, a few key decisions would set the company up as an AI powerhouse and send its stock soaring.

There was a time not so long ago that Microsoft and Intel were both atop the tech world. They were neither competitors nor significant customers of each other, but what New York University’s Adam Brandenburger and Yale’s Barry Nalebuff deemed “complementors.” Microsoft built its hugely profitable Windows operating system over the years to work on computers that used Intel’s chips, and Intel designed new chips to run Windows (hence “Wintel”). The system fueled the leading tech product of the 1990s, the personal computer. Microsoft’s Bill Gates became a celebrity wonk billionaire, and Intel CEO Andy Grove was Time’s 1997 Man of the Year.

Since then their paths have diverged sharply. Microsoft in 2000 was the world’s most valuable company, and after losing that distinction for many years, it’s No. 1 again. Intel was the world’s sixth most valuable company in 2000 and the largest maker of semiconductors; today it’s No. 69 by value and No. 2 in semiconductors by revenue, far behind No. 1 TSMC (and in some years also behind Samsung).

The two tech giants saw their stocks track each other for a while—till Microsoft went on a moonshot.

A Fortune 500 CEO makes thousands of decisions in a career, a few of which will turn out to be momentous. What’s easy to explain in hindsight—that Microsoft would be at the forefront of AI, that Google would become a behemoth, that Blockbuster would fade into obscurity—is never preordained. Often the fateful decisions are identifiable only in retrospect. Nothing more vividly illustrates this than the parallel stories of Microsoft and Intel. The case study of what went right and wrong at those two giant corporations offers a master class in business strategy not just for today’s front-runners at the likes of Google, Open AI, Amazon, and elsewhere—but also for any Fortune 500 leader hoping to survive and thrive in the coming decade.

Wintel’s origin story

The two companies were founded a mere seven years apart. Intel’s founders in 1968 included Robert Noyce, coinventor of the computer chip, and Gordon Moore, who had written the seminal article observing that the number of transistors on a chip doubled every year, which he later revised to two years—Moore’s law, as others later called it. Andy Grove was employee No. 3. All three are still regarded as giants of the industry.

Bill Gates famously dropped out of Harvard to cofound Microsoft with Paul Allen, a childhood friend. They were excited by the prospects of creating software for a new concept, the personal computer, also called a microcomputer. They launched Microsoft in 1975.

Gates and Grove Fortune covers through the decades.

FORTUNE

The two companies’ paths crossed when IBM decided in 1980 to produce a PC and wanted to move fast by using existing chips and an existing operating system developed by others. It chose Intel’s chips and Microsoft’s operating system, profoundly transforming both companies and the people who ran them. IBM’s size and prestige made its design the industry standard, so that virtually all PCs, regardless of manufacturer, used the same Intel chips and Microsoft operating system for decades thereafter. As PCs swept America and the world, Intel and Microsoft became symbols of technology triumphant, glamour, success, and the historic bull market of 1982 to 2000.

Then everything changed.

The reign of Gates and Grove peters out

In October, 2000, Fortune ran an article with an illustration depicting Gates and Grove as monumental Egyptian sphinxes. The headline: “Their Reign Is Over.”

The reasoning: “Gates and Grove attained hegemony by exploiting a couple of key choke points in computer architecture—the operating system and the PC microprocessor,” the article explained. “But in the new, more diverse IT world wired together by universal internet protocols, there are no such obvious choke points to commandeer.”

Thus began a multiyear identity crisis for both companies. Intel’s PC chips and Microsoft’s PC operating system and applications remained bountifully profitable businesses, but both companies and their investors knew those were not the future. So what was? And who would lead this new era?

In January of 2000, Gates stepped down as CEO after 25 years, and Steve Ballmer, Microsoft’s president and a college friend of Gates, took his place; Gates remained chairman. Two days later, Microsoft’s stock rocket ran out of fuel. On that day the company’s market value hit $619 billion, a level it would not reach again for almost 18 years.

Grove was no longer Intel’s CEO in 2000, having handed the job to Craig Barrett, a longtime company executive, in 1998. But as Intel’s visionary and most successful CEO, Grove remained an important presence as chairman of the board. His health was becoming an issue; he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1995, and in 2000 he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Intel’s stock roared until August, when the company’s market value peaked at $500 billion. It has never reached that level since.

But most significantly, 2000 was the year that the internet began to seem like it just might make Wintel irrelevant.

At Intel, Barrett responded with acquisitions, many of which were in telecommunications and wireless technology. In concept, that made great sense. Cell phones were going mainstream, and they required new kinds of chips. “Craig tried to very aggressively diversify Intel by acquiring his way into new businesses,” says David Yoffie, a Harvard Business School professor who was on Intel’s board of directors at the time. “I would say that was not his skill set, and 100% of those acquisitions failed. We spent $12 billion, and the return was zero or negative.”

In the lean years after the dotcom balloon popped, Barrett continued to invest billions in new chip factories, known as fabs, and in new production technologies, so Intel would be well positioned when demand rebounded. That is a hint to one of the most important lessons of the Wintel saga and beyond: Protecting the incumbent business, even in a time of transition, is almost impossible to resist. That course usually sounds reasonable, but it holds the danger of starving the company’s future. As the great management writer Peter Drucker said: “If leaders are unable to slough off yesterday, to abandon yesterday, they simply will not be able to create tomorrow.”

‘We screwed it up’

At Microsoft in the 2000s, “it was not at all obvious what would happen with the shape and volume of PCs, with operating system margins, or the future of applications like Word or Excel,” says Ray Ozzie, a top-level Microsoft executive from 2005 to 2010. “There was significant internal debate at Microsoft and in the industry on whether, in the future, the PC was dead, or if it would continue to grow and thrive.” Maybe Word, Excel, and those other applications that resided on your hard drive would move to the internet, like Google Docs, introduced in early 2006. In that case Microsoft would need a new business model. Should it develop one? Some executives thought so. But no one knew for sure.

During this period, Microsoft was hardly a model of corporate innovation, and succumbed to what often happens when successful companies are disrupted. Ozzie explains: “When you are rolling in resources and there are multiple existential threats, the most natural action to protect the business is to create parallel efforts. It’s more difficult to make a hard opinionated choice and go all in. Unfortunately, by creating parallel efforts, you create silos and internal conflict, which can be dysfunctional.”

As competing teams fought for primacy, Microsoft missed the two most supremely profitable businesses since the PC era: search and cell phones. Those misses were not fatal because Microsoft still had two reliable, highly profitable businesses: the Windows operating system and the Office suite of apps. But in Drucker’s terms, those were yesterday businesses. Investors didn’t see substantial tomorrow businesses, which is why the stock price went essentially nowhere for years. Missing search and cell phones didn’t threaten Microsoft’s existence, but it threatened Microsoft’s relevance and importance in a changing world, which could eventually damage the company’s appeal among investors and the world’s best employees. The reasons for those crucial misses are instructive.

In 2000 Google was an insignificant internet search startup with no clear business model, but it had an inkling that selling advertising could be profitable. We know how that turned out: Google’s 2023 ad revenue was $238 billion. The model was entirely foreign to Microsoft, which made tons of money by creating software and selling it at high prices. Charging users nothing? Selling ads? Microsoft had never run a business at all like Google’s. By the time Google’s model had proved itself, Microsoft was hopelessly far behind. Today its Bing search engine has a 3% market share across all platforms worldwide, says the StatCounter web-traffic analysis firm. Google’s share is 92%.

Google founders Sergey Brin, left and Larry Page threw Microsoft into an identity crisis.

RICHARD KOCI HERNANDEZ—MEDIANEWS GROUP/THE MERCURY NEWS/GETTY IMAGES

Microsoft’s failure in cell phones was, in a large sense, similar—the company didn’t fully grasp the structure of the business until it was too late. The company assumed the cell phone industry would develop much like the PC industry, in which sellers like Dell combined Intel’s chips and Microsoft’s software in a final product. But Apple’s starkly different iPhone business model, in which it designs its own chips and writes its own software, was an enormous hit. The other big winner in the industry, Google’s Android smartphone operating system, likewise ignored the PC model. Instead of selling its operating system, Google gives it away to phone makers like Samsung and Motorola. Google makes money by putting its search engine on every phone and by charging app makers a fee when users buy apps.

Bill Gates acknowledges that Microsoft’s miss in cell phones was life-changing for the company. Looking back on his career in 2020, he said: “It’s the biggest mistake I made in terms of something that was clearly within our skill set.”

Intel also lost the mammoth cell phone opportunity, and in a similar way. It couldn’t adapt. Intel understood the opportunity and was supplying chips for the highly popular BlackBerry phone in the early 2000s. The trouble was, Intel hadn’t designed the chips. They were designed by Arm, a British firm that designs chips but doesn’t manufacture them. Arm had developed a chip architecture that used less power than other chips, a critical feature in a cell phone. Intel was manufacturing the chips and paying a royalty to Arm.

Steve Jobs announces using the Intel processor in Mac computers in his keynote speech at the Moscone Center in 2006. At right is CEO Paul Otellini of Intel.

LIZ HAFALIA—THE SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE/GETTY IMAGES

Understandably, Intel preferred to make phone chips with its own architecture, known as x86. Paul Otellini decided to stop making Arm chips and to create an x86 chip for cell phones—in retrospect, “a major strategic error,” says Yoffie. “The plan was that we would have a competitive product within a year, and we ended up not having a competitive product within a decade,” he recalls. “It wasn’t that we missed it. It was that we screwed it up.”

Groping for a megatrend

Just as 2000 was a turning point for Intel and Microsoft, so was 2013. Broadly they were in the same fix: still raking in money from the businesses that made them great; getting into the next big opportunities too late or unsuccessfully; groping for a megatrend they could dominate. Their stock prices had more or less flatlined for at least a decade. Then, in May 2013, Paul Otellini stepped down as Intel’s CEO. In August, Steve Ballmer announced he would step down as Microsoft’s CEO.

Succession is the board of directors’ No. 1 job, more important than all its other jobs combined. The stakes are always high. How the Intel and Microsoft boards handled their successions, nine months apart, largely explains why the two companies’ storylines have diverged so dramatically.

Under Otellini’s successor, Brian Krzanich, Intel kept missing new-chip deadlines—ironically failing to keep up with Moore’s law even as competitors did so—and lost market share. The company gave up on smartphone chips. After five years as CEO, Krzanich resigned abruptly when an investigation found he had had a consensual relationship with an employee. CFO Bob Swan stepped in as CEO, and the production troubles continued until, by 2021, for the first time in Intel’s existence, its chips were two generations behind competitors’. Those competitors were Taiwan’s TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung.

In crisis mode, Intel’s board brought back Pat Gelsinger, an engineer who had spent 30 years at Intel before leaving for 11 years to be a high-level executive at EMC and then CEO of VMware. As Intel’s CEO he has announced an extraordinarily ambitious and expensive plan to reclaim the company’s stature as the world leader in chip technology.

Microsoft’s board spent almost six months finding Ballmer’s successor under worldwide scrutiny. At least 17 candidates were publicly speculated upon. British and Las Vegas bookies offered odds on the eventual winner; Satya Nadella, who recently marked 10 years as CEO, was a 14-to-1 long shot.

Nadella has arguably been the best corporate succession choice, regardless of industry, in years or perhaps decades. Under his leadership the stock finally broke out of its 14-year trading range and shot upward, rising over 1,000%. Microsoft again became the world’s most valuable company, recently worth $3.1 trillion. Gelsinger, with just over three years in the job, can’t be fully evaluated; industry experts wonder if he’ll be Intel’s Nadella. But both CEOs offer useful examples of how to move a company from the past to the future.

Nadella orchestrated Microsoft’s dramatic turnaround by taking an outsider’s look at the company and making big changes with little drama. He began by making Office apps (Word, Excel) compatible with Apple iPhones and iPads—heresy at Microsoft, which regarded Apple as an archenemy. But Nadella realized the two companies competed very little, and why not let millions more people rely on Office apps? The move sent a message to the company and the world: The Microsoft culture’s endemic arrogance would be dialed down considerably. Interoperating with other companies could now be okay.

That was largely a new business model at the company, with many more to follow. For example, Nadella bought LinkedIn, a player in social media, which Microsoft had entirely missed, and later bought GitHub, a repository of open-source code, which Microsoft had previously despised. Both deals and several others have been standout successes.

More broadly, Nadella brought a new leadership style for a new environment. In a company known for vicious infighting that could paralyze action, he settled long-running debates over major projects. For example, in 2016 he sold the Nokia cell phone business that Microsoft had bought a year before he became CEO, acknowledging that the company had lost the battle for phones. “People don’t quite grok why things have blossomed under Satya,” says a former executive. “His superpower is to make a choice, eliminate conflict, and let the business blossom.”

At Intel, Gelsinger also introduced culture-defying changes. The company had risen to dominance by designing leading-edge chips and manufacturing them with industry-leading skill. Amid that intense pride, the idea of creating a separate foundry business—manufacturing chips designed by others—was anathema. Yet under Gelsinger, Intel has created a new foundry business while also relying more on other foundries, including TSMC, the world’s largest chipmaker, for some of its own chips—a double shock to the culture.

Getting a long-established company with a titanium-strength culture to adopt seemingly strange business models as Nadella and Gelsinger did can be painfully hard. Often only a new CEO can bring the openness necessary to make it happen. The same problem arises when a company needs to update its corporate strategy. Microsoft had been seeking and debating the next big thing for years, but Nadella saw that the company didn’t need to find a potentially huge new future-facing business. It already had one: Azure, its cloud computing service. Amazon Web Services was and is the industry leader, but Azure has grown to a strong No. 2 because Nadella has given it abundant capital and some of the company’s brightest workers. He also made an unorthodox investment in OpenAI, creator of ChatGPT, commiting $13 billion to the company starting before it was famous. Now Azure offers its customers OpenAI technology. In Drucker’s terms, it’s a big, thriving tomorrow business.

Gelsinger changed Intel’s strategy even more radically. He bet heavily and successfully on billions of dollars from the U.S. government. Via the CHIPS and Science Act, Intel could receive up to $44 billion in aid for new U.S. chip factories the company is building in coming years. “As I like to joke, no one has spent more shoe leather on the CHIPS Act than yours truly,” he tells Fortune. “I saw an awful lot of senators, House members, caucuses in the different states. It’s a lot to bring it across the line.”

A key insight is that for a major company with a history of success, like Microsoft and Intel, moving beyond an outmoded strategy and fully embracing a new one is traumatically difficult and sometimes impossible. For years both companies tried and failed to do it. A related insight: Doing it is easier for Nadella and Gelsinger because they have the advantage of being “insider outsiders,” leaders with deep knowledge of their organization but without heavy investment in its strategy; Nadella was working on Azure, not the Windows operating system or Office apps, long before he became CEO, and Gelsinger’s 11-year absence from Intel gave him license to rethink everything.

A larger lesson is that, in the stories of these two great companies, succession is the most important factor. Considering that Microsoft on the whole has fared better than Intel over the past 24 years, it’s significant that over that period, Microsoft has had only two CEOs and Intel has had five. Most people study the CEO when explaining a company’s performance, but they should first examine those who choose the CEO, the board of directors.

Looking back at these stories, asking “what if” is irresistible. What if Paul Otellini had said yes to Steve Jobs? What if any of Intel’s or Microsoft’s CEOs had been someone else? What if Intel, under a different CEO, had developed a successful GPU, the kind of chip that powers today’s AI engines (it tried)—would you ever have heard of Nvidia? Bill Gates said in 2019, “We missed being the dominant mobile operating system by a very tiny amount.” What if that tiny amount had shifted slightly? Whose phone would you be using today?

It’s all endlessly tantalizing but of course unknowable. The value of looking back and asking “what if,” is to remind us that every day leaders are creating the future—and neglecting their duty if they don’t learn from the past.

________________________________________

5 lessons from the Wintel case study:

1. Success can be a company’s worst enemy. The great management writer Peter Drucker said every company must “abandon yesterday” before it can “create tomorrow.” But in a successful company, every incentive pushes leaders to protect yesterday. Intel and Microsoft struggled for years to create their tomorrows.

2. Leaders must be open to business models that seem strange. Whether giving away software or manufacturing chips designed by others as a separate business, both Microsoft and Intel faced competitors doing things differently.

3. Get everyone on the same page. Debate is healthy up to a point, but at Microsoft it continued far too long until Nadella became CEO and set clear priorities. At Intel a series of CEOs backed differing solutions to its declining business, which prolonged a muddled strategy.

4. Succession is the board’s No. 1 job, more important than all its other jobs combined. Everyone knows it, but some boards still do their job poorly. If they make a mistake, none of the other lessons matter. Considering that Microsoft has come through the past 24 years better than Intel, it may be significant that Microsoft has had only two CEOs in that period while Intel has had five.

5. Failure isn’t fatal. The Wintel story is a pointed reminder that all companies, including the best, suffer failures and fall into crises. There are no exceptions. The leaders of any company, even the grandest, must always be ready to engage the skills of organizational rescue, and know that even that can be part of greatness.