1986年,也就是波莱特·帕尔去世前33年,她曾做过一个时髦而比较常规的手术。当时,35岁的帕尔就职于美国赛克斯顿一家医院的人力资源部,赛克斯顿是密苏州中一个位于圣路易斯和孟菲斯之间的小城,人口仅有1.6万人。帕尔已经结婚了,有两个男孩,对整形手术很感兴趣。这类手术被整形医生称为“妈妈变身术”,通过一系列挤捏、塞入、提拉等方式,让女性重回生孩子前的身材。于是,帕尔首次在体内植入了乳房假体。

在接下来的15年里,帕尔经历了丧偶、再婚,在职场中晋升至医院的采购部,她很满意隆胸为她在外貌和心情方面带来的改变。然而,隆胸手术中用的硅胶材料可能导致自身免疫问题和安全隐患,于1992年被美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)列为禁用材料,帕尔开始担心自己。2002年,帕尔发现植入身体的其中一块硅胶出现断裂,硅胶已流入身体,她接受了手术,将体内的硅胶填充假体替换为盐水填充假体。帕尔体内采用了新式的Biocell乳房假体,其外部包裹了一层毛面硅胶外壳,以减少假体的移动。

但是,帕尔之后健康问题不断,她的丈夫也因此起诉了Biocell乳房假体的制造商艾尔建公司,它是美国三大乳房假体制造商之一。2010年,帕尔体内其中一个盐水填充假体出现渗漏,医生将假体换为另一种Biocell毛面假体产品。这一次植入的假体采用硅胶材质,FDA在2006年重新准许硅胶投入使用。

“这种新的乳房假体制作精良,并且由一名颇受好评的医生操刀。”在波莱特去世数月后,她的丈夫卡尔文·帕尔说道,“我们对假体产品从未有过质疑。”

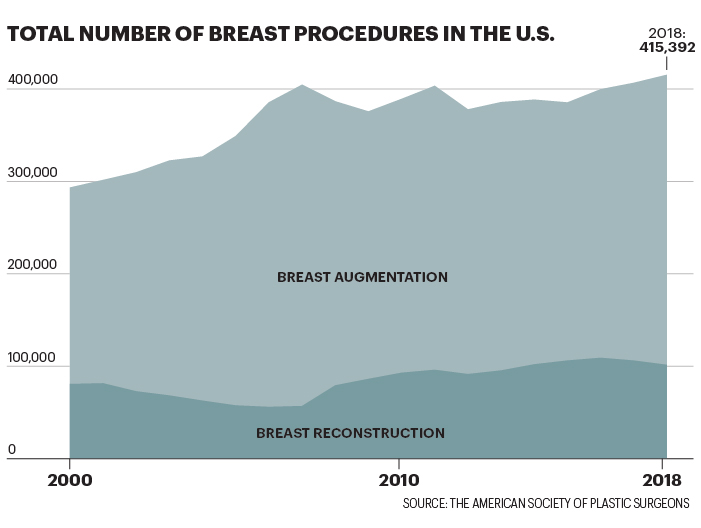

长期以来乳房假体都被视为身材的点睛之笔,人们将它嘲讽为女性的虚荣。而在嘲讽之余,大家却忽视了胸部整形为大量女性顾客带来的严重甚至是致命的健康问题。自2000年,已有超过800万名美国女性曾接受过胸部整形手术;仅在2018年,或为了变美或为了乳房重建,超过40万名女性接受过胸部整形手术。据美国整形外科医生学会统计,隆胸手术是最受欢迎的医美手术。

很多女性非常感激假体的出现,尤其是那些患有乳癌的女性。“接受胸部整形手术是一个非常个人的决定。”现任美国整形外科医生学会主席琳恩·杰弗斯说。她不仅是一名整形医师,还是一位接受过乳房术后重建的癌症康复者。“从我当前的健康数据来看,植入乳房假体没有出现任何不适。”

关于乳房假体产品,虽然曾出现过政府召回、产品责任起诉等问题,但医药公司在销售这类产品时没有太多的顾虑。艾尔建公司于今年5月被艾伯维公司收购,在全球监管部门对其部分产品加以禁止前,该公司在2017年销售过的乳房假体价值总额为3.995亿美元。强生集团旗下的曼托公司是业内的主要竞争者,在销售额方面略逊艾尔建公司一筹。业内还有一家名为Sientra的小型公司,该公司在2019年在乳房假体方面的年收入为4640万美元。

如果拿这些数字与行业巨头艾尔建公司的畅销品保妥适肉毒素瘦脸针的销售额相比,简直相形见绌,保妥适在去年的销售总额为38亿美元。与保妥适瘦脸针相似,乳房假体能为制造商和医生带来可观的重复收入。即使在理想化状态,FDA提醒乳房假体是“不可终生使用的”,每隔10到15年需要更换一次,每次整形手术的价格高达1.2万美元。

关于乳房假体产品,《财富》杂志曾收集过来自医生、患者、律师和公共卫生专家的多方意见,虽然该类产品在数十年来缺乏足够的测试和研究,频繁出现安全问题,监管机制并不完善,但依然被投入到市场中。在许多医疗设备中,无论是用于体外的机器还是植入体内的人造部件,都存在上述问题。然而,由于乳房假体与女性性征和外表相关,它既可用于体态美化,也可作为帮助术后乳癌患者重建正常身材的医疗工具,在近数十年来,减少了乳癌患者的术后困扰。如今,由于监管的缺失而出现越来越多的失败案例,让数百万名女性面临风险。

“有很多女性深受其害。”美国国家卫生研究中心主席戴安娜·扎克曼说,“这些产品被如此广泛地销售着,但每隔几年,我们就会发现产品出现一些新问题。”

乳房假体制造商在设计产品时要兼顾安全和“真实”。目前,市面上的乳房假体主要分为盐水填充式(更易破裂),和硅胶填充式(造型和触感更自然,但常年有安全隐患传闻)。假体的外表分为光面和“毛面”硅胶外壳两种。光面假体在美国更为流行,但医生通常建议乳房切除术后的患者使用毛面假体,因为粗糙的表面更易于组织在假体上生长。

产品因这些差异变化而更易出现问题或副作用,比如:假体出现断裂,疤痕组织会带来疼痛感或使组织硬化;种种症状被统称为“乳房假体疾病”,包括关节疼痛、偏头痛、慢性疲劳,有时免疫系统会出现致命的癌症,这种癌症被称为“乳房假体置入相关的间变性大细胞淋巴瘤”(下文简称淋巴瘤)。

“目前市面上的乳房假体都有问题。”马德里斯·汤姆斯说。她曾是FDA的经理,目前创立Device Events公司,追踪已上报的医疗设备故障。“我不会向任何我在乎的人推荐此类产品。”

人们对于导致乳房假体出现种种问题的原因了解甚少,公共卫生专家将其归咎于缺少测试或缺少研究目的,相关的长期研究没有得到制造商在数据和资金方面的支持。根据FDA的要求,乳房假体制造商需要完整汇报相关数据,在此条件下,硅胶假体在2006年得以重回市场。

从去年起,随着淋巴瘤病例的增多,人们开始意识到有问题的乳房假体产品终将让顾客付出代价。已有903名女性被确诊患有这种罕见肿瘤疾病,33人已因病死亡。预计数十万女性有患病风险,但需要在数十年后出现病症,有研究发现此类病例与毛面乳房假体有关。在接受过胸部整形而罹患淋巴瘤的女性中,她们体内的乳房假体来自于强生、Sientra等不同的生产商。而目前导致最多病例出现的是产自艾尔建公司的Biocell假体。在2018年年底,欧洲监管部门禁止艾尔建公司出售毛面乳房假体。FDA并没有及时应对,但由于淋巴瘤病例的增多,最终在2019年7月要求艾尔建公司召回在售假体产品。艾尔建公司遵守有关规定,暂停相关产品的销售。

截至5月,艾尔建公司已收到48宗起诉,包括与淋巴瘤病例和乳房假体召回相关的共同起诉。这些起诉认为艾尔建公司的Biocell假体存在问题,由此引发人身伤害、经济损失、甚至意外丧命。这些案件已合并为由美国新泽西区法院受理的多区诉讼。

一位艾尔建公司的新闻发言人接受了《财富》杂志的邮件采访,他在邮件中写道,公司不会对暂未判决的诉讼加以评论,还表示“公司始终为患者的健康和安全而努力”,并且“遵照FDA的汇报流程,以透明公开的方式跟进植入过毛面乳房假体顾客的情况。”

在Sientra公司回复《财富》杂志邮件采访时,他们没有将淋巴瘤与毛面假体关联在一起,而强生公司在回复时承认其旗下的曼托公司毛面假体产品引发了“少量淋巴瘤病例”。两家公司均表示患者的安危重于一切。

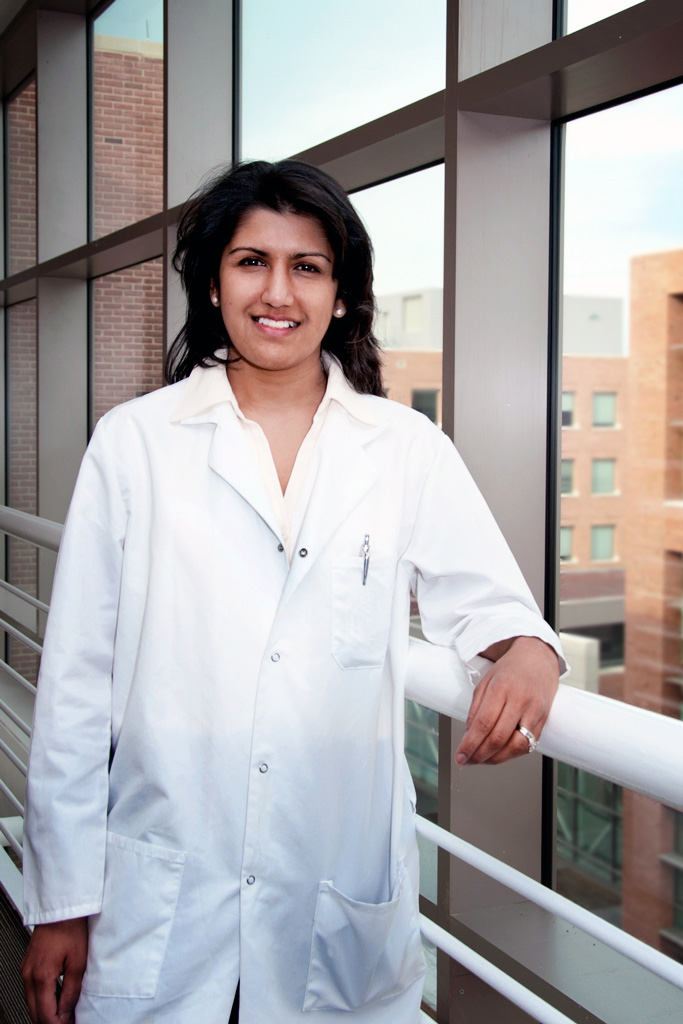

比妮塔·阿沙尔是一名外科医生,同时就职于FDA设备及放射卫生中心,是外科及感染防控设备办公室的主任。她同样认为女性的安全非常重要。“对比十年前,我们现在对乳房假体已经了解了很多,并会继续深入研究。”她说,“为了保护患者的安全,我们必定会进一步采取必要的行动。”

“我的外科医生只是对我说,‘你还记不记得90年代出现过的问题?一切终将得以解决。’”玛丽亚·格米特罗回忆道。医生对乳房假体的风险如此不屑一顾,意味着“患者在做出关于自身健康相关的决定时,没有获得准确的信息。”她说。

格米特罗在2014年植入了曼托公司制造的假体后,出现了皮疹和慢性疲劳的症状,她现在和一大群女性团结在一起,希望医生能对与假体相关的疾病加以重视。淋巴瘤病例的出现让大家开始关注常见的健康问题,比如被统称为“乳房假体疾病”的症状。“乳房假体疾病”暂未有官方的诊断,其症状与自身免疫紊乱相似。脸书中已有10万多人加入一个以乳房假体疾病为主题的群组,组员们一起交流症状,分享移除假体后症状缓解的经历。然而,有患者表示,医生并不理会此类来自于社交平台的医疗信息。

“现在,依然有很多人并不重视乳房假体的问题。”洁梅·库克说。她目前以病人代表的身份与一些整形医生一起加入乳房假体特别研究小组。“但我们能一起探讨,让人们知道我们并没有失去理智,我们是受过教育的女性,同时我们也曾受过伤害。”

这些患者表示,假体已向女性销售多年,但她们并未获得来自生产商或来自医生的适当的提醒,未能让女性行使得知产品风险的权力。现有关于整体医疗设备的追踪非常有限,因为该行业属于分散式管理。FDA仅对生产商进行监管,无法监管医生;生产商将假体销售给整形医生,而患者是假体的终端用户,患者需要自行对体内的假体做好记录。在以前,人们通过一个模拟系统向患者派发一张记录了假体唯一追踪编号的卡片。如果患者将卡片遗失,医生退休,或医生在七年后将记录销毁,很难得知体内究竟植入了哪种假体——该假体是否被召回也不得而知。

人们正在开发一个更好的追踪系统,同时,很多受艾尔建公司召回产品影响的患者表示,她们是通过新闻和社交媒体得知淋巴瘤,而非从医生、艾尔建公司、政府等渠道得知。

“在我买新车时发现车的空气过滤器有问题,汽车销售给我寄了三份保修卡,并打电话提醒我带上保修卡进行售后。”雷琳·霍尔拉说。她是一位乳癌康复者,也是一位曾在2013年被确诊为淋巴瘤的假体患者权益倡导者。“我体内有某种会诱发癌症的东西,FDA已知道这个问题,但我们从未听到相关的提醒吧?”

如果某个医疗设备出现问题,生产商需要将此汇报至美国食品和药物监管局的公开数据库。但在2019年之前,监管局准许公司对设备问题上交一份不公开的“替代性”总结。正因如此,从2009年起,有超过30万例乳房假体问题处于未公开状态,美国食品和药物监管局在去年对此做出承认。“这是一种更高效的方法,当我们发现某个问题,我们直接将它消除。”阿沙尔说。她还补充,那些未公开的报告目前已公之于众。

Device Events公司的汤姆斯说,她曾在2017年与FDA的工作人员会面,告诉他们她发现艾尔建公司偶尔会以“哥斯达黎加”或“圣巴巴拉”的公司名上报设备问题(这两个城市是其工厂的所在地),并非以“艾尔建”这个名字。汤姆斯与《财富》杂志分享了在那次会面中展示的文件,并说道:“如果你是一名医生,你会在FDA的数据库中搜索艾尔建这个名字,而不会搜索哥斯达黎加。他们试图尽可能久地隐瞒问题。”(FDA表示不会对个人会面加以评论。当前的记录已包括公司的名字。)

一名艾尔建公司的新闻发言人表示,公司“一贯遵守FDA的所有要求,其中也包括以不正当形式汇报产品问题”,目前,公司已“对所有瞒报记录提供完整而准确的信息,准确上报公司名称和假体生产地”。

2006年,FDA解除对硅胶乳房假体的禁令,要求生产商对植入硅胶假体的女性进行历时十年的大型研究。去年,强生Mentor和Sientra两家公司因追踪随访的病患人数未能满足标准要求收到了FDA“警告信”。这两家公司获准继续销售其产品;阿沙尔称,FDA“正监督Mentor和Sientra的整改进程”,但不会提供具体细节。强生和Sientra均表示正在努力提高研究过程中的病患参与度。

阿沙尔就此事接受《财富》杂志采访过去一周时间后,FDA又向另外两家乳房假体生产商发出了警告信,称FDA当局“为患者健康不懈努力”。在向艾尔建公司签发的警告信中,FDA指出,艾尔建同样存在召回假体风险研究不充分的缺陷。另一封给私营企业Ideal Implant的警告信中指出,继今年年初FDA对其设施进行检查发现生产和质量控制问题之后,公司采取的整改措施不足;除此之外,公司也未遵守报告假体不良事件的要求。

FDA要求两家公司在警告信发出后15个工作日内作出答复。艾尔建的一位发言人称,公司正在反省警告信指出的缺陷,并“认真重视该问题”。Ideal Implant发言人则表示,公司正在与FDA密切合作,并“坚决支持及时准确地报告产品安全性”。

FDA也在考虑对假体的后期销售进行更积极的监管。去年10月,FDA建议生产商在乳房假体包装上加印更严格的黑框警告,警告内容包括一份清晰的患者决策勾选表格。阿沙尔表示,这份提案收到了1000多条“以赞成为主”的公众评论,她还补充道,“FDA的首要任务就是落实这一指导意见。”

艾尔建的一位女发言人宣称:“女性罹患这种疾病的几率比被雷电击中的概率还低。”这段言论发表于2011年1月,距离第一起乳房假体导致淋巴癌的报道已经过去了十年多。当时,FDA刚刚发布首个公开警告,称植入乳房假体的女性罹患间变性大细胞淋巴瘤(ALCL)“风险可能很小,但几率会增加”。而在密苏里州,波莱特·帕尔刚刚接受了第二套Biocell乳房假体的植入手术。

当时,全球范围内只有大约60起ALCL病例的报道,生产商很快就淡化了假体产品引发的风险。然而,这种威胁(至少威胁到了价格底线)的严重性足以让艾尔建警醒投资者关于该疾病的潜在不良后果,包括负面报道和经济损失。2011年3月,艾尔建发出警告称:“乳房假体产品的生产和销售一直是大量产品责任索赔的对象,这种情况也会持续下去。”

尽管乳房假体业务存在风险,但这并不影响艾尔建作为收购目标的前景。2015年,总部位于都柏林的阿特维斯收购艾尔建,并将艾尔建作为新的公司名称;四年后,首席执行官布伦特·桑德斯同意将合并后的公司出售给修美乐生产商艾伯维。2019年6月,艾伯维宣布收购艾尔建,2020年5月初,艾伯维以630亿美元完成收购。自此,艾伯维的多元化发展深入到了保妥适、乳房假体等其他“医疗美容”领域。桑德斯在接受美国消费者新闻与商业频道(CNBC)旗下知名股评人吉姆·克莱默采访时表示,这是“生物制药领域最好的业务。乳房假体业务持久性极高,在全球范围内都是现金交易,并且受到的监管较少,所以我们不需要和政府采购者打交道。”

随着艾尔建经历多轮并购,接受乳房假体植入手术的女性被诊断出患有乳房植入体相关的间变性大细胞淋巴瘤(BIA-ALCL)的几率也在攀升:从2011年的50万分之一,到2019年的每3800人就有一人患病。Memorial Sloan Kettering癌症中心整形外科医生彼得·科代罗对其患者进行了长达27年的追踪随访,并且他的病患使用的几乎都是艾尔建乳房假体。据他估算,如今他的患者罹患间变性大细胞淋巴瘤的风险为1/355。

但在2018年,这似乎仍未引发FDA担忧,同样不担心这一问题的还有波莱特·帕尔,即便她注意到腋下长了一个痘痘大小的赘生物。做完检查之后,直到11月她才知道自己患上了这种名为BIA-ALCL的癌症。

时年67岁的帕尔已经做了祖母,刚刚退休不久的她利用周末时间短途旅行去往孟菲斯,并期待着自己的第一次纽约之旅。起初,她的诊断结果听起来并没有很严重。医生告诉她,“我给你做6个疗程的化疗,赘生物就会消失。”卡尔文·帕尔回忆说:“这真的让我们松了一口气。”

患有乳腺癌或乳腺癌高风险的女性是一个特别脆弱的群体,而乳房假体问题也使得这一群体的健康状况变得愈发复杂。

每年有超过10万名女性(占与乳房相关的整形手术患者的四分之一)接受乳房“重塑”手术,这类手术多在乳房切除后进行。这些女性并非都是乳腺癌患者;2013年,接受预防性乳房切除手术的人数有所增加,当时,演员安吉丽娜·朱莉检测发现自己携带一种会增加乳腺癌患病风险的基因突变,她投书《纽约时报》专栏,自爆她决定接受预防性双乳房切除手术、植入乳房假体。

如今,这种包含乳房重塑的预防性乳房切除术让众多有恶性癌症家族史、希望降低遗传风险的年轻女性吃了一颗定心丸。对于这些不愿意失去乳房所带来的女性气质或性欲的女性而言,乳房假体已经改变了她们的生活。

纽约市喜剧演员凯特琳·布罗德尼克表示:“作为一个一生都饱受乳腺癌恐惧困扰的人,乳房假体就是一个了不起的安全保障。”她撰写了一本回忆录,讲述她在28岁时决定接受预防性乳房切除和重塑手术。

但颇具讽刺意味的是,许多为了降低患癌风险而接受手术的女性如今却可能会感染这种叫做BIA-ALCL的癌症。

米娅·卡尔根是纽约州韦斯特切斯特县一家幼儿园的主任。她表示:“我们家族的所有女性都死于癌症,这本是一个应该拯救我生命的决定,然后呢,什么!这让我又要面临另一个风险。”她在2014年接受了乳房切除和重塑手术。“压力太大了。生活中的方方面面都受到了影响。“

替换假体,或者哪怕只是移除(“外植”)假体需要再接受一次价格不菲的手术,康复也需要时间。有这样一个备受瞩目的案例:今年3月,曼迪·金斯伯格辞去Match Group首席执行官一职,至于她为什么要离开这家营收高达20亿美元的公司,她表示原因之一在于自己植入的乳房假体产品遭到召回,她刚刚接受了替换假体的手术。

乳房假体还给像波莱特·帕尔这样的女性,以及每年为了美观而接受乳房假体植入手术的数十万女性带来了其他同样严重的影响。对于她们当中的许多人来说,除了巨额的医疗账单外,罹患BIA-ALCL还伴随着自责和别人的指指点点。

米歇尔·福尼是一家金融服务公司的人力资源经理,她如今也患有BIA-ALCL。她表示:“得了这种癌症,别人就会对你评头品足。”米歇尔·福尼是一个乐观开朗的加州人,在谈到对自己的诊断结果感到悔恨时,她的声音变得颤抖,断断续续地说:“这是我自找的。我为了满足虚荣心植入了假体。但我就活该患病吗?”

马克·W·克莱门斯称,淋巴瘤的治疗费用从20万美元到30万美元不等,这还不包括缺勤成本或治疗奔波的路费。作为德克萨斯大学MD安德森癌症中心的整形外科副教授,克莱门斯为许多感染BIA-ALCL的女性提供治疗,同时,他也在准备一项关于该疾病经济影响的研究。他表示:“一些保险公司针对接受隆胸手术的患者制定了保险单除外条款;对被诊断出患有BIA-ALCL的患者做不予承保处理。”

华盛顿州Blue Cross Blue Shield持证保险公司Premera Blue Cross就是其中之一。该保险公司3月出台的一项政策规定,如果患者为了美观植入乳房假体,那么只有在“乳腺间期癌或其他需要切除或部分切除乳房的乳房疾病“的情况下,移除假体的费用才在保险覆盖范围之内。BIA-ALCL不作为乳腺癌或乳房疾病论处。

Premera以患者隐私规定为由拒绝对具体病例发表评论,并指出,目前FDA不建议尚未被诊断出患有BIA-ALCL的女性进行外植手术。Premera补充称,公司会根据具体情况做出决策。Premera首席临床官查德·墨菲在一份电子邮件声明中表示:“每个病例都有其错综复杂之处,这会影响承保范畴的临床决策。“

艾尔建为所有患有BIA-ALCL的女性提供最高7500美元的自费手术费,并承担1000美元的诊断测试费用。对于像福尼和霍尔拉这样已经对艾尔建提起诉讼的女性来说,这些金钱援助远远不够,且为时已晚。福尼表示:“我已经花了数十万美元,并且我有良好的保险保障。癌症就是源源不断的昂贵的‘赐予’。“

2019年初,艾尔建毛面乳房假体在欧洲遭遇禁售后,帕尔移除了她的假体,并继续肿瘤科医生承诺可以消灭她的BIA-ALCL的化疗。她的金色长发开始脱落,最后她让卡尔文用他的理发推子把她的头发都剃光了。

在马里兰州,FDA正在就这种疾病以及乳房假体的整体安全性召开听证会。艾尔建负责假体产品临床开发的副总裁斯蒂芬妮·曼森·布朗博士证实:“有包括毛面假体在内的植入史的患者中已经出现了BIA-ALCL病例的报告。重要的是,该疾病预后良好,早期发现、治疗得当的情况下尤为如此。“

但5月份的时候,FDA表示不会禁止毛面乳房假体,而帕尔的测试结果显示,她的淋巴瘤已经转移。6月份,艾伯维宣布收购艾尔建的计划,此时她已住院一个月,接受了更多的治疗。最终,她的医生告诉她,她的健康状况太差,已经无法接受似乎对其他BIA-ALCL患者有效的实验性治疗。

“她受了很多苦。”卡尔文说,他的南方口音变得更加拖沓。“她的腿非常肿,甚至都无法并拢;胳膊也肿胀起来……然后我们就只能听天由命。“

最终,7月24日,FDA要求艾尔建召回其Biocell毛面乳房假体。FDA随后将此次召回升级为最严重的“I级”,并警告称“使用这些假体可能会造成严重伤害或致死”。

对波莱特·帕尔来说,这一切来得太晚了。召回事件发生29天后,她在圣路易斯医院的病床上度过了68岁生日,然后与世长辞。

对于帕尔的丈夫和他的律师、来自纳什维尔的大卫·兰道夫·史密斯来说,她死于BIA-ALCL就是乳房假体生产商过失行为的证据。但结合其他患者的情况来看,这表明了这样一个从未将患者安全放在首位的全球性行业存在着系统性的问题。

除了帕尔的诉讼外,艾尔建和现在的艾伯维还面临着更多由Biocell引发的多地诉讼。正如1990年代假体生产商道康宁被卷入诉讼的情况一样,针对大型制药公司的大规模诉讼有时可能会导致数十亿美元的赔偿。行业专家表示,现在估算艾伯维的潜在风险还为时过早,但瑞穗高级分析师瓦米尔·迪旺表示,“这绝对是我们正在关注的一个议题。”

但就连原告律师也承认,针对医疗器械制造商的诉讼很难进行,因为个体索赔往往会被FDA的既定产品批准先发制人。艾尔建诉讼案中原告律师詹妮弗·伦茨在描述抢占论点时表示:“即便产品存在问题,你也无权提起诉讼,因为产品已经通过了严格的联邦审批程序。”

无论最终的法律结果如何,乳房假体问题显然对销售造成了影响。甚至在新冠疫情叫停非必要手术之前,整形外科医生的报告就显示隆胸需求出现下降。美国整形外科医生协会前主席斯科特·格拉斯伯格称,在FDA 2019年听证会之后的一年里,“隆胸手术的数量下降了大约10%”,而“移除”手术却出现了大约15%的增长。

3月,比佛利山整形外科医生凯文·布伦纳表示:“我做的假体移除手术比我做的植入手术还要多。”艾尔建召回事件发生后,他的许多患者担心自己会患上淋巴瘤,同时也提高了对于BII的认识。

乳房假体业务最终能否复苏还有待观察,特别是在当下,疫情和随之而来的经济低迷也放大了乳房假体问题。随着消费者削减不必要的支出,隆胸手术继上一次经济衰退后有所下降。在艾伯维5月份的业绩电话会议上,首席执行官理查德·冈萨雷斯承认,他预计隆胸手术数量收缩将对艾尔建的医疗美容业务产生“显著”影响(假设这种影响是“暂时”的话)。

对于卡尔文·帕尔来说,疫情意味着他要一个人住在这个如今空荡荡的房子里,他需要努力适应波莱特离去后所带来的更长久的孤独。他的一个女儿住在街对面,所以他可以去看望孙辈来打发时日。但有时他会半夜醒来,抚摸妻子曾经躺过的那半张床,这才想起来妻子已然辞世。他说:“我没有可以依靠的人了。”

一年前,他还在和波莱特一起规划晚年退休生活。他说:“这辈子我所有的安排都是想要确保波莱特能过得很好。我们知道我会是先离开的那个。但他们害死了她,那该死的假体害了她。”

乳房假体发展简史

围绕乳房假体的争议已有近半个世纪之久。

1976

国会授权FDA监管医疗器械领域。自1962年问世以来,硅胶乳房假体一直沿用至今。

1984

玛丽亚·斯特恩声称因使用道康宁硅胶假体引发疾病,获得150万美元惩罚性损害赔偿。

1992

随着乳房假体诉讼案增多,在国会听证会结束之后,FDA呼吁暂停使用绝大多数硅胶假体产品。

1995

面对高达两万多件官司,道康宁启动美国破产法第11章的破产保护(之后同意以32亿美元达成和解)。乳房假体生产商百时美施贵宝公司、Baxter Healthcare和3M分别为植入硅胶假体受损的女性设立了和解基金。

2006

FDA允许硅胶乳房假体重返美国市场。

2010

一次政府突击检查曝光法国乳房假体生产商PIP公司非法使用工业级硅胶;公司倒闭,创始人被判入狱。

2018

艾尔建毛面乳房假体在欧洲遭遇禁售。

2019年7月

FDA要求艾尔建召回其乳房假体。(财富中文网)

本文刊载于《财富》杂志2020年6/7月刊,文章标题:《存在风险的乳房假体业务》。

译者:杨超 唐尘

1986年,也就是波莱特·帕尔去世前33年,她曾做过一个时髦而比较常规的手术。当时,35岁的帕尔就职于美国赛克斯顿一家医院的人力资源部,赛克斯顿是密苏州中一个位于圣路易斯和孟菲斯之间的小城,人口仅有1.6万人。帕尔已经结婚了,有两个男孩,对整形手术很感兴趣。这类手术被整形医生称为“妈妈变身术”,通过一系列挤捏、塞入、提拉等方式,让女性重回生孩子前的身材。于是,帕尔首次在体内植入了乳房假体。

在接下来的15年里,帕尔经历了丧偶、再婚,在职场中晋升至医院的采购部,她很满意隆胸为她在外貌和心情方面带来的改变。然而,隆胸手术中用的硅胶材料可能导致自身免疫问题和安全隐患,于1992年被美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)列为禁用材料,帕尔开始担心自己。2002年,帕尔发现植入身体的其中一块硅胶出现断裂,硅胶已流入身体,她接受了手术,将体内的硅胶填充假体替换为盐水填充假体。帕尔体内采用了新式的Biocell乳房假体,其外部包裹了一层毛面硅胶外壳,以减少假体的移动。

但是,帕尔之后健康问题不断,她的丈夫也因此起诉了Biocell乳房假体的制造商艾尔建公司,它是美国三大乳房假体制造商之一。2010年,帕尔体内其中一个盐水填充假体出现渗漏,医生将假体换为另一种Biocell毛面假体产品。这一次植入的假体采用硅胶材质,FDA在2006年重新准许硅胶投入使用。

“这种新的乳房假体制作精良,并且由一名颇受好评的医生操刀。”在波莱特去世数月后,她的丈夫卡尔文·帕尔说道,“我们对假体产品从未有过质疑。”

长期以来乳房假体都被视为身材的点睛之笔,人们将它嘲讽为女性的虚荣。而在嘲讽之余,大家却忽视了胸部整形为大量女性顾客带来的严重甚至是致命的健康问题。自2000年,已有超过800万名美国女性曾接受过胸部整形手术;仅在2018年,或为了变美或为了乳房重建,超过40万名女性接受过胸部整形手术。据美国整形外科医生学会统计,隆胸手术是最受欢迎的医美手术。

很多女性非常感激假体的出现,尤其是那些患有乳癌的女性。“接受胸部整形手术是一个非常个人的决定。”现任美国整形外科医生学会主席琳恩·杰弗斯说。她不仅是一名整形医师,还是一位接受过乳房术后重建的癌症康复者。“从我当前的健康数据来看,植入乳房假体没有出现任何不适。”

关于乳房假体产品,虽然曾出现过政府召回、产品责任起诉等问题,但医药公司在销售这类产品时没有太多的顾虑。艾尔建公司于今年5月被艾伯维公司收购,在全球监管部门对其部分产品加以禁止前,该公司在2017年销售过的乳房假体价值总额为3.995亿美元。强生集团旗下的曼托公司是业内的主要竞争者,在销售额方面略逊艾尔建公司一筹。业内还有一家名为Sientra的小型公司,该公司在2019年在乳房假体方面的年收入为4640万美元。

如果拿这些数字与行业巨头艾尔建公司的畅销品保妥适肉毒素瘦脸针的销售额相比,简直相形见绌,保妥适在去年的销售总额为38亿美元。与保妥适瘦脸针相似,乳房假体能为制造商和医生带来可观的重复收入。即使在理想化状态,FDA提醒乳房假体是“不可终生使用的”,每隔10到15年需要更换一次,每次整形手术的价格高达1.2万美元。

关于乳房假体产品,《财富》杂志曾收集过来自医生、患者、律师和公共卫生专家的多方意见,虽然该类产品在数十年来缺乏足够的测试和研究,频繁出现安全问题,监管机制并不完善,但依然被投入到市场中。在许多医疗设备中,无论是用于体外的机器还是植入体内的人造部件,都存在上述问题。然而,由于乳房假体与女性性征和外表相关,它既可用于体态美化,也可作为帮助术后乳癌患者重建正常身材的医疗工具,在近数十年来,减少了乳癌患者的术后困扰。如今,由于监管的缺失而出现越来越多的失败案例,让数百万名女性面临风险。

“有很多女性深受其害。”美国国家卫生研究中心主席戴安娜·扎克曼说,“这些产品被如此广泛地销售着,但每隔几年,我们就会发现产品出现一些新问题。”

乳房假体制造商在设计产品时要兼顾安全和“真实”。目前,市面上的乳房假体主要分为盐水填充式(更易破裂),和硅胶填充式(造型和触感更自然,但常年有安全隐患传闻)。假体的外表分为光面和“毛面”硅胶外壳两种。光面假体在美国更为流行,但医生通常建议乳房切除术后的患者使用毛面假体,因为粗糙的表面更易于组织在假体上生长。

产品因这些差异变化而更易出现问题或副作用,比如:假体出现断裂,疤痕组织会带来疼痛感或使组织硬化;种种症状被统称为“乳房假体疾病”,包括关节疼痛、偏头痛、慢性疲劳,有时免疫系统会出现致命的癌症,这种癌症被称为“乳房假体置入相关的间变性大细胞淋巴瘤”(下文简称淋巴瘤)。

“目前市面上的乳房假体都有问题。”马德里斯·汤姆斯说。她曾是FDA的经理,目前创立Device Events公司,追踪已上报的医疗设备故障。“我不会向任何我在乎的人推荐此类产品。”

人们对于导致乳房假体出现种种问题的原因了解甚少,公共卫生专家将其归咎于缺少测试或缺少研究目的,相关的长期研究没有得到制造商在数据和资金方面的支持。根据FDA的要求,乳房假体制造商需要完整汇报相关数据,在此条件下,硅胶假体在2006年得以重回市场。

从去年起,随着淋巴瘤病例的增多,人们开始意识到有问题的乳房假体产品终将让顾客付出代价。已有903名女性被确诊患有这种罕见肿瘤疾病,33人已因病死亡。预计数十万女性有患病风险,但需要在数十年后出现病症,有研究发现此类病例与毛面乳房假体有关。在接受过胸部整形而罹患淋巴瘤的女性中,她们体内的乳房假体来自于强生、Sientra等不同的生产商。而目前导致最多病例出现的是产自艾尔建公司的Biocell假体。在2018年年底,欧洲监管部门禁止艾尔建公司出售毛面乳房假体。FDA并没有及时应对,但由于淋巴瘤病例的增多,最终在2019年7月要求艾尔建公司召回在售假体产品。艾尔建公司遵守有关规定,暂停相关产品的销售。

截至5月,艾尔建公司已收到48宗起诉,包括与淋巴瘤病例和乳房假体召回相关的共同起诉。这些起诉认为艾尔建公司的Biocell假体存在问题,由此引发人身伤害、经济损失、甚至意外丧命。这些案件已合并为由美国新泽西区法院受理的多区诉讼。

一位艾尔建公司的新闻发言人接受了《财富》杂志的邮件采访,他在邮件中写道,公司不会对暂未判决的诉讼加以评论,还表示“公司始终为患者的健康和安全而努力”,并且“遵照FDA的汇报流程,以透明公开的方式跟进植入过毛面乳房假体顾客的情况。”

在Sientra公司回复《财富》杂志邮件采访时,他们没有将淋巴瘤与毛面假体关联在一起,而强生公司在回复时承认其旗下的曼托公司毛面假体产品引发了“少量淋巴瘤病例”。两家公司均表示患者的安危重于一切。

比妮塔·阿沙尔是一名外科医生,同时就职于FDA设备及放射卫生中心,是外科及感染防控设备办公室的主任。她同样认为女性的安全非常重要。“对比十年前,我们现在对乳房假体已经了解了很多,并会继续深入研究。”她说,“为了保护患者的安全,我们必定会进一步采取必要的行动。”

“我的外科医生只是对我说,‘你还记不记得90年代出现过的问题?一切终将得以解决。’”玛丽亚·格米特罗回忆道。医生对乳房假体的风险如此不屑一顾,意味着“患者在做出关于自身健康相关的决定时,没有获得准确的信息。”她说。

格米特罗在2014年植入了曼托公司制造的假体后,出现了皮疹和慢性疲劳的症状,她现在和一大群女性团结在一起,希望医生能对与假体相关的疾病加以重视。淋巴瘤病例的出现让大家开始关注常见的健康问题,比如被统称为“乳房假体疾病”的症状。“乳房假体疾病”暂未有官方的诊断,其症状与自身免疫紊乱相似。脸书中已有10万多人加入一个以乳房假体疾病为主题的群组,组员们一起交流症状,分享移除假体后症状缓解的经历。然而,有患者表示,医生并不理会此类来自于社交平台的医疗信息。

“现在,依然有很多人并不重视乳房假体的问题。”洁梅·库克说。她目前以病人代表的身份与一些整形医生一起加入乳房假体特别研究小组。“但我们能一起探讨,让人们知道我们并没有失去理智,我们是受过教育的女性,同时我们也曾受过伤害。”

这些患者表示,假体已向女性销售多年,但她们并未获得来自生产商或来自医生的适当的提醒,未能让女性行使得知产品风险的权力。现有关于整体医疗设备的追踪非常有限,因为该行业属于分散式管理。FDA仅对生产商进行监管,无法监管医生;生产商将假体销售给整形医生,而患者是假体的终端用户,患者需要自行对体内的假体做好记录。在以前,人们通过一个模拟系统向患者派发一张记录了假体唯一追踪编号的卡片。如果患者将卡片遗失,医生退休,或医生在七年后将记录销毁,很难得知体内究竟植入了哪种假体——该假体是否被召回也不得而知。

人们正在开发一个更好的追踪系统,同时,很多受艾尔建公司召回产品影响的患者表示,她们是通过新闻和社交媒体得知淋巴瘤,而非从医生、艾尔建公司、政府等渠道得知。

“在我买新车时发现车的空气过滤器有问题,汽车销售给我寄了三份保修卡,并打电话提醒我带上保修卡进行售后。”雷琳·霍尔拉说。她是一位乳癌康复者,也是一位曾在2013年被确诊为淋巴瘤的假体患者权益倡导者。“我体内有某种会诱发癌症的东西,FDA已知道这个问题,但我们从未听到相关的提醒吧?”

如果某个医疗设备出现问题,生产商需要将此汇报至美国食品和药物监管局的公开数据库。但在2019年之前,监管局准许公司对设备问题上交一份不公开的“替代性”总结。正因如此,从2009年起,有超过30万例乳房假体问题处于未公开状态,美国食品和药物监管局在去年对此做出承认。“这是一种更高效的方法,当我们发现某个问题,我们直接将它消除。”阿沙尔说。她还补充,那些未公开的报告目前已公之于众。

Device Events公司的汤姆斯说,她曾在2017年与FDA的工作人员会面,告诉他们她发现艾尔建公司偶尔会以“哥斯达黎加”或“圣巴巴拉”的公司名上报设备问题(这两个城市是其工厂的所在地),并非以“艾尔建”这个名字。汤姆斯与《财富》杂志分享了在那次会面中展示的文件,并说道:“如果你是一名医生,你会在FDA的数据库中搜索艾尔建这个名字,而不会搜索哥斯达黎加。他们试图尽可能久地隐瞒问题。”(FDA表示不会对个人会面加以评论。当前的记录已包括公司的名字。)

一名艾尔建公司的新闻发言人表示,公司“一贯遵守FDA的所有要求,其中也包括以不正当形式汇报产品问题”,目前,公司已“对所有瞒报记录提供完整而准确的信息,准确上报公司名称和假体生产地”。

2006年,FDA解除对硅胶乳房假体的禁令,要求生产商对植入硅胶假体的女性进行历时十年的大型研究。去年,强生Mentor和Sientra两家公司因追踪随访的病患人数未能满足标准要求收到了FDA“警告信”。这两家公司获准继续销售其产品;阿沙尔称,FDA“正监督Mentor和Sientra的整改进程”,但不会提供具体细节。强生和Sientra均表示正在努力提高研究过程中的病患参与度。

阿沙尔就此事接受《财富》杂志采访过去一周时间后,FDA又向另外两家乳房假体生产商发出了警告信,称FDA当局“为患者健康不懈努力”。在向艾尔建公司签发的警告信中,FDA指出,艾尔建同样存在召回假体风险研究不充分的缺陷。另一封给私营企业Ideal Implant的警告信中指出,继今年年初FDA对其设施进行检查发现生产和质量控制问题之后,公司采取的整改措施不足;除此之外,公司也未遵守报告假体不良事件的要求。

FDA要求两家公司在警告信发出后15个工作日内作出答复。艾尔建的一位发言人称,公司正在反省警告信指出的缺陷,并“认真重视该问题”。Ideal Implant发言人则表示,公司正在与FDA密切合作,并“坚决支持及时准确地报告产品安全性”。

FDA也在考虑对假体的后期销售进行更积极的监管。去年10月,FDA建议生产商在乳房假体包装上加印更严格的黑框警告,警告内容包括一份清晰的患者决策勾选表格。阿沙尔表示,这份提案收到了1000多条“以赞成为主”的公众评论,她还补充道,“FDA的首要任务就是落实这一指导意见。”

艾尔建的一位女发言人宣称:“女性罹患这种疾病的几率比被雷电击中的概率还低。”这段言论发表于2011年1月,距离第一起乳房假体导致淋巴癌的报道已经过去了十年多。当时,FDA刚刚发布首个公开警告,称植入乳房假体的女性罹患间变性大细胞淋巴瘤(ALCL)“风险可能很小,但几率会增加”。而在密苏里州,波莱特·帕尔刚刚接受了第二套Biocell乳房假体的植入手术。

当时,全球范围内只有大约60起ALCL病例的报道,生产商很快就淡化了假体产品引发的风险。然而,这种威胁(至少威胁到了价格底线)的严重性足以让艾尔建警醒投资者关于该疾病的潜在不良后果,包括负面报道和经济损失。2011年3月,艾尔建发出警告称:“乳房假体产品的生产和销售一直是大量产品责任索赔的对象,这种情况也会持续下去。”

尽管乳房假体业务存在风险,但这并不影响艾尔建作为收购目标的前景。2015年,总部位于都柏林的阿特维斯收购艾尔建,并将艾尔建作为新的公司名称;四年后,首席执行官布伦特·桑德斯同意将合并后的公司出售给修美乐生产商艾伯维。2019年6月,艾伯维宣布收购艾尔建,2020年5月初,艾伯维以630亿美元完成收购。自此,艾伯维的多元化发展深入到了保妥适、乳房假体等其他“医疗美容”领域。桑德斯在接受美国消费者新闻与商业频道(CNBC)旗下知名股评人吉姆·克莱默采访时表示,这是“生物制药领域最好的业务。乳房假体业务持久性极高,在全球范围内都是现金交易,并且受到的监管较少,所以我们不需要和政府采购者打交道。”

随着艾尔建经历多轮并购,接受乳房假体植入手术的女性被诊断出患有乳房植入体相关的间变性大细胞淋巴瘤(BIA-ALCL)的几率也在攀升:从2011年的50万分之一,到2019年的每3800人就有一人患病。Memorial Sloan Kettering癌症中心整形外科医生彼得·科代罗对其患者进行了长达27年的追踪随访,并且他的病患使用的几乎都是艾尔建乳房假体。据他估算,如今他的患者罹患间变性大细胞淋巴瘤的风险为1/355。

但在2018年,这似乎仍未引发FDA担忧,同样不担心这一问题的还有波莱特·帕尔,即便她注意到腋下长了一个痘痘大小的赘生物。做完检查之后,直到11月她才知道自己患上了这种名为BIA-ALCL的癌症。

时年67岁的帕尔已经做了祖母,刚刚退休不久的她利用周末时间短途旅行去往孟菲斯,并期待着自己的第一次纽约之旅。起初,她的诊断结果听起来并没有很严重。医生告诉她,“我给你做6个疗程的化疗,赘生物就会消失。”卡尔文·帕尔回忆说:“这真的让我们松了一口气。”

患有乳腺癌或乳腺癌高风险的女性是一个特别脆弱的群体,而乳房假体问题也使得这一群体的健康状况变得愈发复杂。

每年有超过10万名女性(占与乳房相关的整形手术患者的四分之一)接受乳房“重塑”手术,这类手术多在乳房切除后进行。这些女性并非都是乳腺癌患者;2013年,接受预防性乳房切除手术的人数有所增加,当时,演员安吉丽娜·朱莉检测发现自己携带一种会增加乳腺癌患病风险的基因突变,她投书《纽约时报》专栏,自爆她决定接受预防性双乳房切除手术、植入乳房假体。

如今,这种包含乳房重塑的预防性乳房切除术让众多有恶性癌症家族史、希望降低遗传风险的年轻女性吃了一颗定心丸。对于这些不愿意失去乳房所带来的女性气质或性欲的女性而言,乳房假体已经改变了她们的生活。

纽约市喜剧演员凯特琳·布罗德尼克表示:“作为一个一生都饱受乳腺癌恐惧困扰的人,乳房假体就是一个了不起的安全保障。”她撰写了一本回忆录,讲述她在28岁时决定接受预防性乳房切除和重塑手术。

但颇具讽刺意味的是,许多为了降低患癌风险而接受手术的女性如今却可能会感染这种叫做BIA-ALCL的癌症。

米娅·卡尔根是纽约州韦斯特切斯特县一家幼儿园的主任。她表示:“我们家族的所有女性都死于癌症,这本是一个应该拯救我生命的决定,然后呢,什么!这让我又要面临另一个风险。”她在2014年接受了乳房切除和重塑手术。“压力太大了。生活中的方方面面都受到了影响。“

替换假体,或者哪怕只是移除(“外植”)假体需要再接受一次价格不菲的手术,康复也需要时间。有这样一个备受瞩目的案例:今年3月,曼迪·金斯伯格辞去Match Group首席执行官一职,至于她为什么要离开这家营收高达20亿美元的公司,她表示原因之一在于自己植入的乳房假体产品遭到召回,她刚刚接受了替换假体的手术。

乳房假体还给像波莱特·帕尔这样的女性,以及每年为了美观而接受乳房假体植入手术的数十万女性带来了其他同样严重的影响。对于她们当中的许多人来说,除了巨额的医疗账单外,罹患BIA-ALCL还伴随着自责和别人的指指点点。

米歇尔·福尼是一家金融服务公司的人力资源经理,她如今也患有BIA-ALCL。她表示:“得了这种癌症,别人就会对你评头品足。”米歇尔·福尼是一个乐观开朗的加州人,在谈到对自己的诊断结果感到悔恨时,她的声音变得颤抖,断断续续地说:“这是我自找的。我为了满足虚荣心植入了假体。但我就活该患病吗?”

马克·W·克莱门斯称,淋巴瘤的治疗费用从20万美元到30万美元不等,这还不包括缺勤成本或治疗奔波的路费。作为德克萨斯大学MD安德森癌症中心的整形外科副教授,克莱门斯为许多感染BIA-ALCL的女性提供治疗,同时,他也在准备一项关于该疾病经济影响的研究。他表示:“一些保险公司针对接受隆胸手术的患者制定了保险单除外条款;对被诊断出患有BIA-ALCL的患者做不予承保处理。”

华盛顿州Blue Cross Blue Shield持证保险公司Premera Blue Cross就是其中之一。该保险公司3月出台的一项政策规定,如果患者为了美观植入乳房假体,那么只有在“乳腺间期癌或其他需要切除或部分切除乳房的乳房疾病“的情况下,移除假体的费用才在保险覆盖范围之内。BIA-ALCL不作为乳腺癌或乳房疾病论处。

Premera以患者隐私规定为由拒绝对具体病例发表评论,并指出,目前FDA不建议尚未被诊断出患有BIA-ALCL的女性进行外植手术。Premera补充称,公司会根据具体情况做出决策。Premera首席临床官查德·墨菲在一份电子邮件声明中表示:“每个病例都有其错综复杂之处,这会影响承保范畴的临床决策。“

艾尔建为所有患有BIA-ALCL的女性提供最高7500美元的自费手术费,并承担1000美元的诊断测试费用。对于像福尼和霍尔拉这样已经对艾尔建提起诉讼的女性来说,这些金钱援助远远不够,且为时已晚。福尼表示:“我已经花了数十万美元,并且我有良好的保险保障。癌症就是源源不断的昂贵的‘赐予’。“

2019年初,艾尔建毛面乳房假体在欧洲遭遇禁售后,帕尔移除了她的假体,并继续肿瘤科医生承诺可以消灭她的BIA-ALCL的化疗。她的金色长发开始脱落,最后她让卡尔文用他的理发推子把她的头发都剃光了。

在马里兰州,FDA正在就这种疾病以及乳房假体的整体安全性召开听证会。艾尔建负责假体产品临床开发的副总裁斯蒂芬妮·曼森·布朗博士证实:“有包括毛面假体在内的植入史的患者中已经出现了BIA-ALCL病例的报告。重要的是,该疾病预后良好,早期发现、治疗得当的情况下尤为如此。“

但5月份的时候,FDA表示不会禁止毛面乳房假体,而帕尔的测试结果显示,她的淋巴瘤已经转移。6月份,艾伯维宣布收购艾尔建的计划,此时她已住院一个月,接受了更多的治疗。最终,她的医生告诉她,她的健康状况太差,已经无法接受似乎对其他BIA-ALCL患者有效的实验性治疗。

“她受了很多苦。”卡尔文说,他的南方口音变得更加拖沓。“她的腿非常肿,甚至都无法并拢;胳膊也肿胀起来……然后我们就只能听天由命。“

最终,7月24日,FDA要求艾尔建召回其Biocell毛面乳房假体。FDA随后将此次召回升级为最严重的“I级”,并警告称“使用这些假体可能会造成严重伤害或致死”。

对波莱特·帕尔来说,这一切来得太晚了。召回事件发生29天后,她在圣路易斯医院的病床上度过了68岁生日,然后与世长辞。

对于帕尔的丈夫和他的律师、来自纳什维尔的大卫·兰道夫·史密斯来说,她死于BIA-ALCL就是乳房假体生产商过失行为的证据。但结合其他患者的情况来看,这表明了这样一个从未将患者安全放在首位的全球性行业存在着系统性的问题。

除了帕尔的诉讼外,艾尔建和现在的艾伯维还面临着更多由Biocell引发的多地诉讼。正如1990年代假体生产商道康宁被卷入诉讼的情况一样,针对大型制药公司的大规模诉讼有时可能会导致数十亿美元的赔偿。行业专家表示,现在估算艾伯维的潜在风险还为时过早,但瑞穗高级分析师瓦米尔·迪旺表示,“这绝对是我们正在关注的一个议题。”

但就连原告律师也承认,针对医疗器械制造商的诉讼很难进行,因为个体索赔往往会被FDA的既定产品批准先发制人。艾尔建诉讼案中原告律师詹妮弗·伦茨在描述抢占论点时表示:“即便产品存在问题,你也无权提起诉讼,因为产品已经通过了严格的联邦审批程序。”

无论最终的法律结果如何,乳房假体问题显然对销售造成了影响。甚至在新冠疫情叫停非必要手术之前,整形外科医生的报告就显示隆胸需求出现下降。美国整形外科医生协会前主席斯科特·格拉斯伯格称,在FDA 2019年听证会之后的一年里,“隆胸手术的数量下降了大约10%”,而“移除”手术却出现了大约15%的增长。

3月,比佛利山整形外科医生凯文·布伦纳表示:“我做的假体移除手术比我做的植入手术还要多。”艾尔建召回事件发生后,他的许多患者担心自己会患上淋巴瘤,同时也提高了对于BII的认识。

乳房假体业务最终能否复苏还有待观察,特别是在当下,疫情和随之而来的经济低迷也放大了乳房假体问题。随着消费者削减不必要的支出,隆胸手术继上一次经济衰退后有所下降。在艾伯维5月份的业绩电话会议上,首席执行官理查德·冈萨雷斯承认,他预计隆胸手术数量收缩将对艾尔建的医疗美容业务产生“显著”影响(假设这种影响是“暂时”的话)。

对于卡尔文·帕尔来说,疫情意味着他要一个人住在这个如今空荡荡的房子里,他需要努力适应波莱特离去后所带来的更长久的孤独。他的一个女儿住在街对面,所以他可以去看望孙辈来打发时日。但有时他会半夜醒来,抚摸妻子曾经躺过的那半张床,这才想起来妻子已然辞世。他说:“我没有可以依靠的人了。”

一年前,他还在和波莱特一起规划晚年退休生活。他说:“这辈子我所有的安排都是想要确保波莱特能过得很好。我们知道我会是先离开的那个。但他们害死了她,那该死的假体害了她。”

乳房假体发展简史

围绕乳房假体的争议已有近半个世纪之久。

1976

国会授权FDA监管医疗器械领域。自1962年问世以来,硅胶乳房假体一直沿用至今。

1984

玛丽亚·斯特恩声称因使用道康宁硅胶假体引发疾病,获得150万美元惩罚性损害赔偿。

1992

随着乳房假体诉讼案增多,在国会听证会结束之后,FDA呼吁暂停使用绝大多数硅胶假体产品。

1995

面对高达两万多件官司,道康宁启动美国破产法第11章的破产保护(之后同意以32亿美元达成和解)。乳房假体生产商百时美施贵宝公司、Baxter Healthcare和3M分别为植入硅胶假体受损的女性设立了和解基金。

2006

FDA允许硅胶乳房假体重返美国市场。

2010

一次政府突击检查曝光法国乳房假体生产商PIP公司非法使用工业级硅胶;公司倒闭,创始人被判入狱。

2018

艾尔建毛面乳房假体在欧洲遭遇禁售。

2019年7月

FDA要求艾尔建召回其乳房假体。(财富中文网)

本文刊载于《财富》杂志2020年6/7月刊,文章标题:《存在风险的乳房假体业务》。

译者:杨超 唐尘

Thirty-three years before her death, Paulette Parr visited her doctor for a popular and relatively routine procedure. It was 1986, and Parr was 35, working in human resources at the local hospital in Sikeston, a 16,000-person Missouri enclave midway between St. Louis and Memphis. A married mother of two young boys, she was interested in what plastic surgeons still call a “mommy makeover,” a catchall for the various procedures that nip, tuck, and lift women back to a pre-childbirth shape. For Parr, that meant getting her first set of breast implants.

For the next 15 years, through losing her first husband and remarrying and getting promoted to her hospital’s purchasing department, Parr was mostly happy with her implants, and with how they made her look and feel. But they were silicone-based, a type the U.S. Food and Drug Administration banned in 1992 over concerns that they were causing autoimmune and safety problems, and Parr eventually started to worry about them. So by 2002, when she learned that one of her implants had ruptured and was leaking silicone into her body, Parr’s surgeon replaced them with saline-filled versions. Her new Biocell implants were covered in a roughly textured silicone shell, designed to reduce movement of the device.

That’s when Parr’s implant-related health problems really began, according to a lawsuit her husband has filed against pharmaceutical company Allergan, the maker of Biocell products and one of three major manufacturers of American breast implants. In 2010, after one of her saline implants started leaking, her plastic surgeon replaced them with yet another set of Biocell textured implants, this time filled with silicone, which the FDA had allowed back onto the market in 2006.

“They were gorgeous, and they were put in by a reputable doctor,” says Paulette’s widower, Calvin Parr, months after her death. “We never gave it a second thought.”

Breast implants have long been a punch line, mocked as frivolous markers of female vanity. But that dismissive attitude overlooks a business with a serious and sometimes deadly impact on the health of its overwhelmingly female customer base. More than 8 million American women have undergone breast-related plastic surgeries since 2000; in 2018 alone, more than 400,000 women chose one for either cosmetic or reconstructive reasons. Breast augmentation is the most popular cosmetic procedure tracked by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

Many women, especially those affected by breast cancer, say they are grateful to have implants as an option. “It’s a decision that’s personal,” says Lynn Jeffers, the society’s current president, a plastic surgeon, and a cancer survivor who’s getting post-mastectomy reconstruction. “With the data that I have now, I’m comfortable having implants.”

And pharmaceutical companies have been very comfortable selling them, despite a long history of government recalls and product-liability lawsuits. Allergan, which was acquired by AbbVie in May, sold $399.5 million worth of implants in 2017, before regulators around the globe started banning some of its products. Its main rival, Johnson & Johnson, doesn’t break out results for its Mentor Worldwide breast implant business. Smaller specialist Sientra reported annual “breast products” revenues of $46.4 million in 2019.

Those numbers pale in comparison to blockbusters like Allergan bestseller Botox, which raked in $3.8 billion last year. But like Botox, breast implants can have attractive recurring revenue built in for manufacturers and the doctors who use their products. Even under ideal circumstances, breast implants “are not lifetime devices,” the FDA warns, and will likely need to be replaced every 10 to 15 years, for a cost of up to $12,000 per cosmetic procedure.

Yet as doctors, patients, lawyers, and public health experts tell Fortune, breast implants have remained on the market despite decades of inadequate testing and study, recurrent safety concerns, and poor regulatory oversight. Those problems plague many medical devices, which range from machines used outside the body to artificial parts implanted within it. But breast implants are unique in their affiliation with female sexuality and physical appearance, their intersecting roles as elective beauty products and clinical tools that can help cancer survivors feel more like themselves—and the degree to which patients’ mounting concerns about them have been dismissed for decades. Now, that accumulated failure of oversight has created sweeping, sometimes tragic crises for potentially millions of women.

“There are a lot of women who are really suffering,” says Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research. “You have these products that are widely, widely sold, and every few years we learn something new about the problems they cause.”

Breast implant makers walk a particularly fine line when it comes to creating a product that is both safe and “realistic.” Today’s implants are either filled with saline (more likely to break) or silicone (more natural looking and feeling but plagued by a history of safety concerns). Their exteriors can be either smooth or made of a “textured” silicone shell. Smooth implants are more popular in the U.S., but surgeons working with mastectomy patients sometimes prefer textured versions, because the products’ rougher surface enables tissue to grow onto the implant more easily.

All of these variations are prone to malfunctions or side effects, which can include ruptured implants; a buildup of scar tissue that can cause pain and tissue hardening; a large collection of symptoms often known as “breast implant illness,” which can include joint pain, migraines, and chronic fatigue; and, increasingly, a sometimes fatal cancer of the immune system known as ¬BIA-ALCL, for “breast implant–¬associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma.”

“The breast implants that are on the market right now all have issues,” says Madris Tomes, a former FDA manager who tracks reported medical device failures at her Device Events firm. “I wouldn’t recommend them to anyone that I care about.”

The causes of the various problems with breast implants are still poorly understood, which public health experts blame on a lack of testing or objective, long-term studies that do not rely on manufacturer-provided data or funding. Device makers also have yet to fully report the data the FDA required as a condition of allowing silicone implants back on the market in 2006.

The cost of embracing such troubled devices became painfully clear last year, after a surge in cases of BIA-ALCL. More than 903 women have now been diagnosed with that once-rare lymphoma, and more than 33 have died. Hundreds of thousands of others are estimated to be at risk of developing the disease, which can take decades to surface and has been linked to textured implants in academic studies. Cases of the lymphoma have been reported in women with implants from various manufacturers, including Johnson & Johnson and Sientra. But Allergan’s Biocell implants have by far the worst record of affected patients. By the end of 2018, European regulators stopped Allergan from selling textured implants. The FDA was slower to respond, but in July 2019 it finally asked Allergan to recall those devices from the market, citing BIA-ALCL. The company complied and suspended future sales.

By May, Allergan was facing about 48 lawsuits, including some class action claims, related to BIA-ALCL and its recalled implants. Alleging that problems with Allergan Biocell implants have caused injury, financial losses, and wrongful death, these cases have now been consolidated in a multi-district litigation in the U.S. District of New Jersey.

An Allergan spokesperson told Fortune via email that the company does not comment on pending litigation, adding that it “has a demonstrated history of dedication to the health and safety of patients” and “has followed FDA regulatory reporting procedures and acted transparently with patients about textured breast implants.”

In emailed statements to Fortune, Sientra did not address the linkages of BIA-ALCL to its textured implants, while Johnson & Johnson acknowledged “a low number of BIA-ALCL cases reported” in Mentor textured implants. Both companies said they prioritized the safety of their patients.

Binita Ashar, a general surgeon and director of the FDA’s Office of Surgical and Infection Control Devices in the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, also calls women’s safety a priority. “We know more about breast implants today than we did 10 years ago, and we continue to learn more,” she says. “We will not hesitate to take further action if necessary to protect patients.”

“My surgeon basically told me, ‘Remember all the issues from the ’90s? They fixed all that,’ ” recalls Maria Gmitro. Such dismissals of the risks involved with breast implants mean “patients do not have accurate information to make informed choices about our health,” she says.

Gmitro, who says she developed rashes and chronic fatigue after buying Mentor implants in 2014, is part of a growing cohort of women trying to get doctors to take implant-related health complaints more seriously. BIA-ALCL has drawn attention to more common health issues, including the constellation of symptoms known as “breast implant illness.” BII does not have an official diagnosis; some of its symptoms resemble autoimmune disorders. One Facebook group devoted to BII has more than 100,000 members, who trade symptoms and stories of relief after removing their implants—but patients say many doctors are quick to dismiss medical information that comes from such sources.

“Even now there’s a large part of the community that’s not taken seriously,” says Jamee Cook, a patient advocate who’s now on a breast implant task force with plastic surgeons. “But we’ve been able to sit at the table and have people realize that we’re not crazy, we’re educated women, and we have been harmed.”

At the very least, these patients say, implants have been marketed to women for years without adequate warnings from either manufacturers or surgeons, denying women their right to informed consent about the risks involved. Little tracking of medical devices exists in general, owing in part to the decentralized nature of the business. The FDA regulates manufacturers, not doctors; manufacturers sell their implants to plastic surgeons, yet patients are the end users and the ones in charge of keeping track of which implants they have. Historically, this was done through the extremely analog system of giving patients a card with their implants’ unique tracking number on it. If you lose that piece of paper, and your surgeon retires or destroys records after seven years, good luck figuring out which breast implants you got—or whether they’ve been recalled.

While better tracking systems are being developed, many patients affected by the Allergan recall say they found out about BIA-ALCL from the news or social media rather than from their doctors, Allergan, or the government.

“When I bought a new car that turned out to have a faulty air filter, my car dealer sent me three postcards and followed up with a phone call reminding me to bring it in,” says Raylene Hollrah, a breast cancer survivor and implant patient advocate who was diagnosed with BIA-ALCL in 2013. “But I have something in my body that causes a cancer that the FDA knew about—and hear nothing?”

When a medical device malfunctions, manufacturers are required to report it to the FDA’s publicly available database. But until 2019, the agency also allowed companies to file private “alternative” summaries of malfunctions. These allowed more than 300,000 reports of breast implant problems to remain hidden since 2009, the FDA acknowledged last year. “This was an approach to be more efficient, and when we recognized that there was a concern, we eliminated it,” says Ashar, adding that the reports are now public.

Tomes of Device Events says she met with the FDA in 2017 to discuss her findings that Allergan had, in some instances, reported problems with devices under the company name “Costa Rica” or “Santa Barbara” (locations where their implants were made), but not under “Allergan.” She shared documents from the meeting with Fortune, saying: “If you’re a physician, you go to the FDA database, and you’re going to look up the name Allergan, not Costa Rica. They were putting off the identification of the problems as long as they could.” (The FDA says it does not comment on individual meetings. The records now include the company name.)

An Allergan spokesperson says the company has “always worked to fully meet all FDA requirements, including our adverse event reporting obligations” and that it currently sends “all adverse event reports to FDA with full and accurate information using the company name and manufacturing location of the implant.”

When the FDA lifted its ban on silicone implants in 2006, it required manufacturers to conduct large, 10 year studies of the women who have their implants. Last year, Mentor and Sientra received “warning letters” from the FDA over their failure to track enough women over time. Both have been allowed to continue selling their products; Ashar says the FDA is “monitoring Mentor and Sientra’s progress” but would not provide specifics. J&J and Sientra both say they are working to increase patient participation in their studies.

A week after Ashar spoke with Fortune for this story, the FDA sent two more warning letters to breast implant manufacturers, citing its “ongoing efforts to protect patients.” One letter, to Allergan, said the company also failed to adequately study the risks of its now-recalled implants once they were on the market. The other letter, to privately-held Ideal Implant, said the company has failed to fix manufacturing and quality-control problems the FDA discovered during an inspection earlier this year. Ideal is also violating requirements for reporting problems with its implants, according to the letter.

The FDA gave both companies 15 working days to respond to its warnings. An Allergan spokesperson said the company is reviewing the letter and “takes this matter seriously.” A spokesperson for Ideal Implant said the company is working closely with the FDA and “strongly supports timely and accurate reporting on product safety.”

The agency is also considering more proactive regulation of future implant sales. In October, the FDA proposed adding a more severe black-box warning label to breast implants, along with an explicit patient-decision checklist. The proposal received more than 1,000 “mostly favorable” public comments, according to Ashar, who adds that “finalizing the guidance is a top priority for the agency.”

“A woman is more likely to be struck by lightning than get this condition,” an Allergan spokeswoman declared. It was January 2011, more than a decade after the first reported case of lymphoma tied to breast implants. The FDA had just issued its first public warning that women with breast implants “may have a very small but increased risk of developing” a disease then called anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). And in Missouri, Paulette Parr had just gotten her second set of Biocell implants.

At the time, there had been only about 60 cases of ALCL reported worldwide, and manufacturers were quick to downplay the risks. Yet the danger—at least to its bottom line—was grave enough for Allergan to warn investors about the potential negative consequences of the disease, including bad press and financial losses. “The manufacture and sale of breast implant products has been and continues to be the subject of a significant number of product liability claims,” the company warned in March 2011.

The risks of the breast implant business hasn’t dented the company’s prospects as an acquisition target. In 2015, Dublin-based Actavis bought Allergan and assumed its name; four years later, CEO Brent Saunders agreed to sell the combined company to AbbVie, maker of Humira. The $63 billion deal, announced in June 2019 and closed in early May, enables AbbVie to diversify into Botox, breast implants, and the other “medical aesthetics” which, Saunders told CNBC’s Jim Cramer, is “the best business in the biopharmaceuticals space. It’s highly durable, it’s cash pay all over the world, and it’s less regulated, so we don’t have to deal with government payers,” he said.

As Allergan rode the M&A merry-go-round, the chances that a woman with breast implants would be diagnosed with BIA-ALCL climbed from one in 500,000 in 2011 to one in 3,800 in 2019. Peter Cordeiro, a Memorial Sloan Kettering plastic surgeon who followed his patients for 27 years and almost exclusively used Allergan implants, estimates that his patients now have a one in 355 chance of developing the cancer.

But in 2018, the FDA still didn’t seem worried and neither was Paulette Parr—even when she noticed a pimple-size growth under her arm. She went in to have it checked, only to learn in November that she had this thing called BIA-ALCL.

Parr was 67 then, a newly retired grandmother, taking weekend jaunts to Memphis and looking forward to visiting New York City for the first time. And at first, her diagnosis didn’t sound so dire. The doctor told her, “You give me six sessions of chemo, it’ll be gone,” Calvin Parr recalls. “That relieved us really well.”

Problems with implants have increasingly complicated the health of one particularly vulnerable community: women with or at high risk of developing breast cancer.

Every year, more than 100,000 women—a quarter of breast-related plastic surgery patients—have “reconstructive” procedures, mostly after mastectomies. They don’t all have the disease; preventive mastectomies got a boost in 2013, when actor Angelina Jolie, who has a gene mutation that puts her at increased risk for breast cancer, wrote a New York Times op-ed about her decision to preventively remove her breasts and replace them with implants.

Today, such prophylactic mastectomies with reconstruction have become a reassurance for many young women who have seen their mothers and aunts and grandmothers die from aggressive cancers and who want to reduce their own hereditary risks. For these women, who don’t want to lose the femininity or sexuality associated with having breasts, implants have been life-changing devices.

“As somebody who was plagued with a fear of breast cancer my whole life, there was this amazing safety net,” says Caitlin Brodnick, a New York City comedian and the author of a memoir about her decision to have a preventive mastectomy and reconstructive surgery at age 28.

But one terrible irony of ¬BIA-ALCL is that many women who had the surgery to reduce their risk of cancer could now contract a new type.

“To lose all the women in my family to cancer, to make this decision that is supposed to save my life—and then, just kidding! This put me at a whole other risk,” says Mia Kargen, a nursery school director in Westchester County, N.Y., who underwent the double procedure in 2014. “It was so stressful. It affects every part of life.”

Replacing implants or even simply removing (“explanting”) them requires another expensive surgery and time for recovery. In one high-profile instance, Match Group CEO Mandy Ginsberg in March stepped down from her $2-billion-in-revenue company, citing in part the surgery she had just undergone to replace her recalled breast implants.

There are separate, equally devastating effects for women like Paulette Parr and the hundreds of thousands of others who still get implants every year for cosmetic reasons. For many of them, developing BIA-ALCL has come with a side of self-recrimination and external criticism—not to mention massive medical bills.

“With this cancer, you’re judged,” says Michelle Forney, an HR manager at a financial services company who has now developed BIA-ALCL. A briskly upbeat Californian, her voice falters and breaks as she talks about the guilt she felt about her diagnosis: “I gave it to myself. I put these implants in for vanity. But do I deserve this?”

Costs for treating the lymphoma can run from $200,000 to $300,000, not including the costs of missing work or traveling for treatment, according to Mark W. Clemens. An associate professor of plastic surgery at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Clemens is treating many of the women who have contracted BIA-ALCL and preparing a study of its financial impact. “For patients who received a cosmetic augmentation, some insurers have policy exclusions; they will not cover a patient who’s been diagnosed,” he says.

One such insurer is Premera Blue Cross, a Washington State licensee of Blue Cross Blue Shield. A policy from March states that if a patient’s implants were placed for cosmetic purposes, removing them is covered only “if there has been interval development of breast cancer or other breast disease that requires mastectomy or partial mastectomy.” BIA-ALCL is not considered a breast cancer or disease.

Premera declined to comment on specific cases, citing patient privacy rules, and noted that the FDA does not currently recommend explantation if women have not been diagnosed with BIA-ALCL. The insurer added that it makes decisions on a case-by-case basis. “Each case has its own intricacies that guide the clinical decision of coverage,” Chad Murphy, Premera’s chief clinical officer, said in an emailed statement.

Allergan has offered up to $7,500 to cover out-of-pocket surgery costs to any woman who has developed BIA-ALCL, and $1,000 toward diagnostic testing. That’s too little, too late for women like Forney and Hollrah, who have filed suit against Allergan. “It has cost me thousands and thousands of dollars, and I have good insurance,” says Forney. “Cancer is an expensive gift that keeps on giving.”

In early 2019, after Europe halted sales of Allergan’s textured implants, Parr had hers removed and continued the chemo her oncologist promised would eliminate her BIA-ALCL. Her long blond hair started to fall out, and she eventually asked Calvin to cut it all off with his barber clippers.

In Maryland, the FDA was convening hearings to discuss the disease and the overall safety of breast implants. “Cases of BIA-ALCL have been reported in patients with an implant history that includes textured implants,” Dr. Stephanie Manson Brown, Allergan’s VP of clinical development for devices, testified. “What is important is that the prognosis is excellent, especially when identified early and treated appropriately.”

But in May, as the FDA said it would not ban textured breast implants, Parr’s tests showed that her lymphoma had metastasized. In June, as AbbVie announced its plans to buy Allergan, she spent the month hospitalized and undergoing more treatments. Eventually, her doctors told her that her health was too poor for her to qualify for an experimental treatment that seems to be effective for other patients with BIA-ALCL.

“She suffered an awful lot,” Calvin says, his Southern drawl thickening. “Her legs got so big that she couldn’t even put them together, her arms swelled up … and then we were just sitting and waiting for the end.”

Finally, on July 24, the FDA asked Allergan to recall its Biocell textured implants. The agency would later upgrade the recall to its most serious “Class I” designation, warning that “use of these devices may cause serious injuries or death.”

It all came too late for Paulette Parr. Twenty-nine days after the recall, after spending her 68th birthday in a St. Louis hospital bed, she died.

To Parr’s husband and his lawyer, Nashville-based David Randolph Smith, her death from BIA-ALCL is evidence of one implant-maker’s negligence. But when grouped with others, it suggests a systemic failure in a global industry that had never put patient safety first.

Parr’s lawsuit is part of the Biocell-related multi-district litigation Allergan, and now AbbVie, are facing. Large-scale suits against big pharma companies can sometimes result in multibillion-dollar payouts, as happened in the 1990s against implant maker Dow Corning. Industry experts say it’s too early to estimate AbbVie’s potential exposure, but “it’s definitely an issue we’re watching,” says Mizuho senior analyst Vamil Divan.

But even the plaintiffs’ lawyers acknowledge that lawsuits against medical device manufacturers are difficult to pursue, because individual claims filed are often preempted by the FDA’s preexisting approval of the products. “Even if there is something wrong with this product, you are not entitled to bring this action, because it has already gone through this strict federal approval process,” is how Jennifer Lenze, a lawyer representing the plaintiffs in the Allergan litigation, describes the preemption argument.

Whatever the eventual legal outcome, the problems with breast implants are clearly affecting their sales. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down elective procedures, plastic surgeons were reporting a drop in demand. Scot Glasberg, a former president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, says that in the year following the FDA’s 2019 hearings, “we have seen the number of breast augmentations go down about 10%,” with “explants” up about 15%.

“I’ve been taking out more implants than I’ve been putting in,” Kevin Brenner, a Beverly Hills plastic surgeon, said in March. The Allergan recall made many of his patients concerned about developing the lymphoma, but also raised awareness about BII, he says.

Whether the breast implant business will eventually recover remains to be seen—especially now that its problems have been amplified by the pandemic and resulting economic downturn. Breast augmentations fell after the last recession, as consumers cut back on nonessential spending. During AbbVie’s May earnings call, CEO Richard Gonzalez acknowledged that he expects the contraction to have a “pronounced” if “transient” impact on Allergan’s medical aesthetics business.

For Calvin Parr, the pandemic means rattling around the house he shared with Paulette and trying to get used to a more permanent sort of isolation. One of his daughters lives across the street, so he’s able to break up the days with visits from his grandchildren. But sometimes he wakes up at night and feels the bed for his wife, before remembering she is gone. “I’ve got nobody to hang on to,” he says.

A year ago, he and Paulette were still planning the rest of their retirement together. “All of our life, I was the one making arrangements to make sure Paulette would be taken care of. We knew I’d be going first,” he says. “But then they killed her. The damn implants killed her.”

A brief history of breast implants

The devices are approaching a half-century of controversy.

1976

Congress gives the FDA the authority to regulate medical devices. Silicone breast implants, on the market since 1962, are grand¬fathered in.

1984

Maria Stern, who claims her Dow Corning silicone implants made her sick, wins $1.5 million in punitive damages.

1992

After more lawsuits and congressional hearings, the FDA calls for a moratorium on most silicone implants.

1995

Dow Corning, facing more than 20,000 lawsuits, files for Chapter 11 (it would later agree to a $3.2 billion settlement). Separately, manufacturers Bristol-Myers Squibb, Baxter Healthcare, and 3M establish a settlement fund for women with damaged silicone implants.

2006

The FDA allows silicone breast implants back on the U.S. market.

2010

A government raid uncovers French implant maker Poly Implant Prothese’s use of an unapproved industrial-grade silicone; it shutters and its founder is jailed.

2018

Europe halts sales of Allergan’s textured implants.

July 2019

The FDA asks Allergan to recall the devices.

A version of this article appears in the June/July 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline "The Risky Business of Breast Implants."