去年秋天,奥黛丽•格尔曼似乎登上了商界顶峰——至少也是为商界增添了一抹色彩。

32岁那年,这位来自纽约、人脉甚广的前政治活动家为the Wing募集了超过1.17亿美元的风险投资。The Wing是奥黛丽在2016年与同伴合作成立的高档女性俱乐部兼联合办公企业。

来自洛杉矶和伦敦等地的女性纷纷涌向the Wing色调柔和的办公室和众星云集的晚会。在这里,影视明星和总统候选人们谈论着“追求自己想要的”和“开辟自己的道路”等话题。

2019年9月,格尔曼登上了某期专门介绍女性创业者的《Inc.》杂志封面,庆祝事业和个人生活双丰收。

照片中的她怀孕八个月,气场全开。

“我希望所有女性都看到这个封面,鼓起信心面对更多职业风险,同时也不要放弃她们做母亲和组建家庭的梦想,”格尔曼在该封面发行当日的早晨对《今日秀》说道。

之后,事态走向了崩塌。一些黑人顾客在社交媒体和新闻中称,对the Wing和那里“白人居多”的场合感到不适。

今年三月,《纽约时报杂志》发表长篇报道,谈及the Wing内部员工口中的“有毒文化”,包括对钟点工收入和调度的投诉,以及对管理层不作为的抱怨等内容。例如,有一名顾客称黑色和棕色皮肤员工为“有色女孩”。

之后,the Wing的实体办公场所因新冠疫情关闭停摆,经营前景陷入困境。明尼阿波利斯市警方致乔治•弗洛伊德死亡事件又掀起了全国抵制种族歧视的热潮,放大了女性对the Wing的不满之声。她们声称the Wing未能践行其“姐妹情深”的女权主义说辞。一些在职和离职员工,包括很多疫情期间遭解雇的员工,均抵制该公司对“黑人的命也是命”运动做出的回应,并质疑格尔曼的领导能力。

六月中旬,顶着不断增加的压力和审视目光,格尔曼辞去了CEO一职。

“最终,公司的成长凌驾于文化之上,这是以牺牲有色女性获得力量的权利为代价的,”她在Instagram上写道,“我没能践行自己设立的价值观。”

格尔曼的瞬间失宠极具戏剧性,但并非个例。每当员工控诉管理不善或遭受虐待时,媒体通常会进行放大,每一位深陷其中的创始人都会在18个月内辞职或被迫离开公司。

运动服初创公司Outdoor Voices创始人泰勒•哈尼;箱包公司Away创始人斯蒂芬•科里;女性数字出版商Refinery29总编克莉丝汀•巴巴里克;制衣和服装品牌Reformation创始人雅艾尔•阿夫拉洛;零售品牌Ban.do创始人珍•高奇;工作场所福利平台Cleo创始人香农•斯帕哈克以及心理健康平台Crisis Text Line创始人南希•卢布林等女性,都遭遇了类似情况。

虽然每个人的卸任经历各有曲折,但这些公司和创始人有很多共同之处——这类公司都是快速成长型初创企业,强调女权主义或肩负着社会驱动使命。它们获得了风险资本的支持,或是已出售给了私有企业主。多数公司推出了面向消费者的产品。它们绝大多数都是由年轻富有的白人或亚裔创立的,且创始人已经成为了公司的“形象代言”。

对了,有人认为最重要的一点,是这些公司都是由女性成立的。

对于众多硅谷人士来说,业内多位杰出女性创始人的下台,这是令人不安的事情。

Winnie联合创始人兼CEO萨拉•莫斯科普夫称,“只有极少数女性能够真正得到媒体和众人的关注,但她们通常会在某一时刻黯然消失。”Winnie是一家成立于旧金山的儿童托育平台,已募集到1550万美元。

除此之外,其他一些女性创始人虽然掌管着公司,其管理风格和文化模式却面临着严苛的审视,包括皮肤护理初创企业Glossier、零售商Rent the Runway,交友应用软件Bumble和内衣公司ThirdLove的几名CEO。

很难不令人疑惑,正如莫斯科普夫说的那样:“到底怎么了?为什么只有女性出事?”

为了理解莫斯科普夫和其他24位接受《财富》杂志专访的创始人、投资者、高管和初创企业员工中多数人的担忧,应当从女性领导的初创企业现状着手,全局性地分析问题。

女性创始人的成功有迹可循。一项2018年波士顿咨询公司(BCG)的研究发现,女性创立的企业每投资一美元获取的收益是男性创立企业的两倍,但绝大多数投资者却会避开她们。2019年,初创企业获得的风险资本总额中,成员均为女性的创业团队仅获得了2.6%。2018和2019两年中,黑人女性获得的风投资金还不足0.3%。女性募集的资金数量仅为男性的三分之一左右,且不太可能在后续几轮中再次拿到资金。女性在公司中持有的股本较少,致使她们将更多的控制权让给了那些有权解雇或保护她们的投资者。

Crunchbase公司的数据显示,在价值超过10亿美元的“独角兽”初创企业中,只有4%是由女性创始人兼CEO经营的。这意味着,就比例来说,拥有创业资本支持的成功女性创始人甚至比《财富》500强女性CEO还罕见,而全美国7.4%的大型公司是由后者经营的。

显而易见,本次新冠疫情给女性创业者带来了经济灾难,使得本就困难的局面雪上加霜。

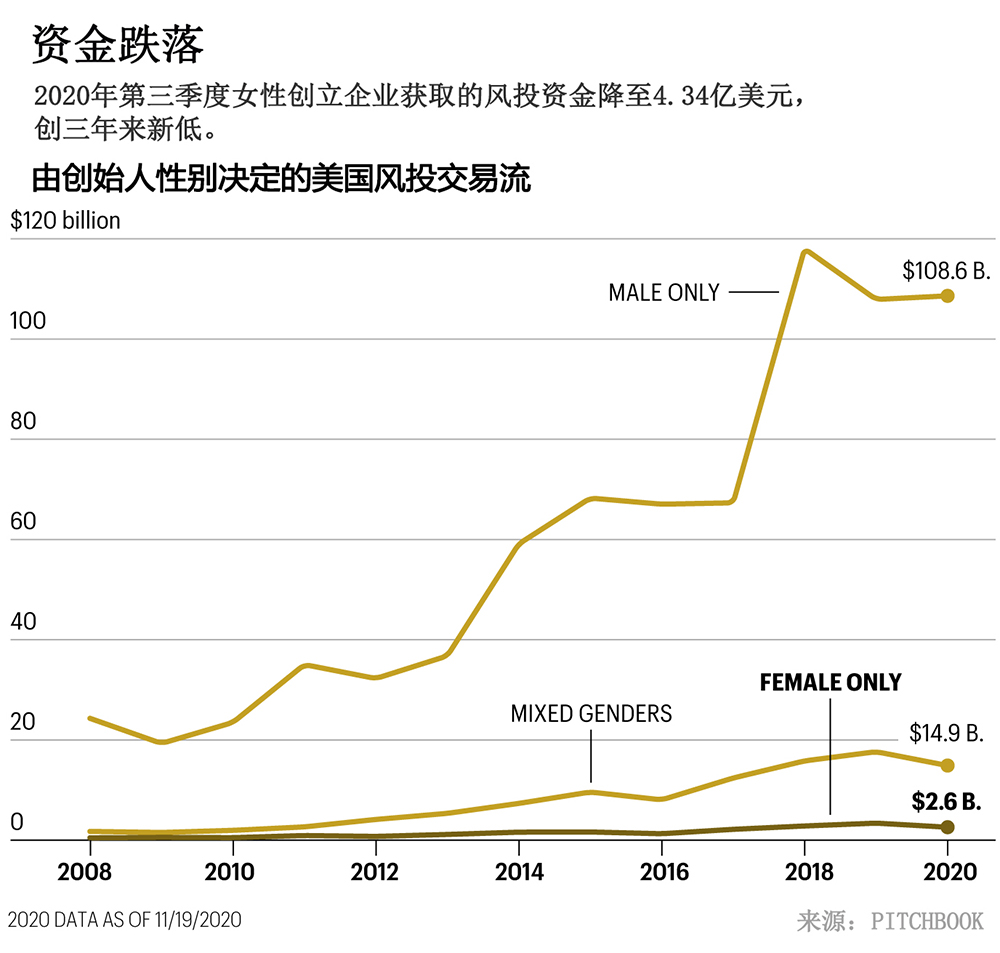

十月份,数据公司PitchBook报告称,第三季度女性创立企业获取的风投资金降至4.34亿美元,创三年来新低。同时期初创企业获得的投资总额378亿美元中,女性初创企业仅获得约1%。

投资者和企业家称,目前全球的不确定性又进一步强化了风险资本孤立和注重模式匹配的实质。在这些风险投资中,88%的投资决策者是男性,男性成立的公司被视为默认“安全”的赌注。

硅谷资深高管帕姆•科斯克塔称,“困难时期,一些人不过是回归到固有的模式识别上,他们的标准操作行为就是投给男性创始人。”科斯克塔目前经营着非盈利组织 All Raise,致力于女性风投和帮助女性创始人。

上述趋势,与一连串备受关注的女性创始人下台事件相结合,正引发一场初创企业业内人士愈演愈烈的讨论:女性创始人是否正遭到抵制,使得她们更容易受到公众的监督,最终导致,与男性同僚相比,她们被迫离开公司的可能性更大。

The Coven是一家位于明尼阿波利斯市的女性联合办公初创企业。其联合创始人兼CEO亚历克斯•韦斯特•斯坦曼称,“显然,女性面临着双重标准,”大量社会学研究和随处可见的现实经验也证明,“我们无论何时都背负着目标,但人们总希望我们失败。”

商界女性面临着所谓的“双重束缚”,她们会因“不像女人”的行为而受到谴责,但这些行为在男性领导身上却是值得期待和赞赏的。2007年,纽约大学研究人员领导的一项研究发现,当使用同样的人格特征描述两名性别相异的管理人员时,“女性显然更不讨喜”且“更易被视为不受欢迎的老板。”男女领导拥有同样行为时,男性总是被视为是坚强、坚决和果断的,而女性则被认为是激进、粗暴或无理取闹的。

不过,也不是每个人都认为初创企业中存在的性别歧视。

“创业者很难做,但竞争环境还是相对公平的,”31岁的亚历克莎•冯•托贝尔说道。她将自己的金融规划服务初创公司LearnVest卖给了西北互助人寿保险公司(Northwestern Mutual)。目前,亚历克莎正经营着刚成立不久的风险投资公司Inspired Capital。

对于莫斯科普夫所提出的商界的失势“只会发生在女性身上” 这种说法,亚历克莎持反对意见,并举例比如令人震惊的WeWork联合创始人亚当•诺依曼和优步(Uber)联合创始人特拉维斯•卡兰尼克下台事件,以及最近发生的尼古拉(Nikola)创始人特雷弗•米尔顿辞职事件。

同时,今年有几家公司的员工在新闻媒体、社交媒体和几场诉讼案中,就男性创始人兼CEO的领导能力和职场文化问题也进行了投诉。这些公司包括社交网站Pinterset,服饰品牌埃韦兰斯(Everlane)和股权服务公司Carta(至少到目前为止,这几名创始人仍然在职)。

保险科技公司Policygenius联合创始人兼CEO詹妮弗•菲茨杰拉德称,“面试时,人们首先提及的就是文化,”她的保险公司已从私人投资者处筹资超过1.62亿美元。她表示,当员工在社交媒体或新闻中苛责CEO时,“与其说是性别问题,不如说是人们脾气变得更加暴躁、平台变大以及员工的容忍度降低了。”

现实情况可能更微妙些,但并不意外。在许多此类事件中,值得询问的是,这些女性创始人是否本身也设置了陷阱,让自己往里跳。

例如,Outdoor Voices创始人泰勒•哈尼于2014年成立了在Instagram上颇受欢迎的运动服饰公司,并于五年内筹资超过6000万美元。她似乎走着和格尔曼相同的路线:在众多杂志封面上亮相;2019《纽约客》刊登了她的大篇幅介绍,将她评为“最佳品牌典范”;在七月的《早安美国》节目中,她宣布自己怀孕了,并激励女权主义者;“作为一名年轻的女性创始人兼CEO,你不必在事业和家庭间做选择,这真是太棒了。”

但今年2月,还在休产假的哈尼透露她正准备离开公司。不久后,有报道称,在她的监管下,Outdoor Voices不仅烧钱、延迟门店开张,还失去了富有经验的高管。员工向BuzzFeed新闻匿名投诉,声称虽然跟着号称“鼓舞人心”的年轻女性创始人工作,却发现哈尼引领着一种不正常的偏袒文化。

哈尼在Outdoor Voices的地位降低了。她在接受《Inc.》杂志采访时承认,该品牌“在适当的情况下确实会抛出‘女创始人’的故事......我们就是靠这个来发展品牌的,而且我们成了新闻媒体的宠儿。但直到它失效前,一切都很好,因为我们也成为了新闻媒体重点关注的对象。”

正如哈尼和格尔曼一样,许多离职或最近备受指责的女企业家们似乎都在走同一条路——创立以消费者为导向的品牌,并使自己成为公司的公众面孔。如果创立的品牌出售的是打底裤,而非云计算公司的软件,这种模式就更常见了。

Acrew Capital创始合伙人特蕾莎•格武称这类企业“更受新闻媒体青睐,因为更适合一般读者,这是两全其美的。”虽然确有女性成立高端技术公司,但也只是少数。

PitchBook和All Raise数据显示,去年,零售和消费类公司风险投资金额中,有30%流向了至少由一位女性创始人设立的初创企业。但在科技初创企业中,该份额降至19%。

零售/消费领域人满为患,因此,抱着将创始人当成明星的想法,并采用宣扬女权主义崛起的营销方式,一直是由女性领导的初创企业应对质疑的方法。但这也公然将女性创始人与公司的失败联系在了一起,尤其体现在承诺为代表性不足的顾客发声,和为雇员创造更良好空间方面。

“在女权主义基础上建立独角兽规模的公司,这个领域是很难涉足的。一旦看上去不够真诚,那就很危险了,”连续创业家凯瑟琳•康纳斯说道。她现在是网络创业公司League of Badass Women的CEO。

几位企业家告诉我,这种视创始人为中心、打着“女性创业为女性”旗号的营销方式,经常是受到初创企业风险投资方的“指令”,投资者迫使创业者选择将其创业公司打造成“女性生活方式”企业,否则就得不到融资。

“我们是粉红投资组合,”康纳斯说道。“我们假定,利用女权主义和女性客户保证盈利,在公司的估值达到10亿美元的时候,我们就可以套现离场。”

莫斯科普夫称,就在她和她的女性联合创始人为其软件平台集资时,一位潜在投资人问她们为何“不经常上新闻”,以及她们是否能尝试“创立一个类似TheSkimm的品牌”。 TheSkimm是一家媒体公司,除了创始人也是两位女性以外,和Winnie几乎没有共同点。“我们只希望人们能使用Winnie,”莫斯科普夫说。“顾客不需要考虑我和我的联合创始人。”

这就要谈到科技行业和媒体之间的爱恨情仇了。

很多创业生态系统内部人士斥责道,记者“打造”出年轻美丽的女性创始人,只是为了最后毁掉她们。这些女性的崛起的确在一定程度上得益于包括《财富》杂志在内的商业出版物,和主要报道商业女性的女记者,比如我。(在加入《财富》杂志前,我为《Inc.》编辑了与格尔曼封面孕肚照相关的女性创始人系列章节)。我们也有责任报道这些公司的失败,但当掌权者是一位女性时,这类报道常会遭到口诛笔伐,说我们带有偏见或是骗点击量。

2019年12月,科技媒体the Verge报道Away CEO斯蒂芬•科里深夜向员工发送言辞激烈、带有“侮辱性”的Slack信息,并希望员工取消假期回来加班。报道刊登后,科里暂时辞职。今年夏天她在Instagram上强烈反抗:“我不并想说究竟发生了什么,只想在社交媒体上写点东西给大家看,”她写道。“为何总针对女性?因为读者看她们登高跌重的故事看得津津有味。”

科里于今年1月重新担任公司的联合CEO,而后又于10月再次辞职,她拒绝评论此事。但许多初创企业业内人士则声称,男性领导人做出类似或更糟糕的行为时,却往往能侥幸逃脱。(详见《财富》2020年度商业人物埃隆•马斯克。)

“成长期的公司并不适合所有人,这是个不可告人的秘密。很多这类公司的文化都有问题,” Female Founders Alliance创始人莱斯莉•芬扎格说道。

相反,很少有女性能确保募集到大量风投资金,无论她们是否愿意这么想,她们都无可避免地被推上了All Raise科斯克塔口中的“完美基座”上,受到媒体、员工和投资者的密切注视。众目睽睽之下,她们本能地害怕自己变成下一个倒霉蛋。

“每次有人倒下,我就会收到女性创业者发来的信息,写的都是,‘什么鬼东西?’以及,‘何时会轮到我?’等等”风险投资公司NEA合伙人瓦妮莎•拉克说道,“这太可怕了,根本不公平。”

甚至一些把创始人投诉至辞职的初创公司员工也承认,他们对女性创始人有更多的诉求。部分原因在于,少数登上“完美基座”的女性通常是享有特权的白人,她们经常承诺,企业终将为黑皮肤和棕色皮肤的钟点工提供更好的机会。

“女性肩负着更沉重的责任。在男性主导的社会中,这就是女性要面对的。”莱斯利安•艾力•圣地亚哥说道。她是一名波多黎各黑人,也是Reformation的前商店经理助理,“但创立并非只为白人女性服务的企业,也是她们的职责”。

2020年反种族主义抗议不仅加剧了对女性创业者的强烈抵制,也让人们更清楚地看到性别双重标准的真容。

直接对比男性和女性领导的公司不易得出结论,不过Reformation的案例却很相近。这家由前模特雅艾尔•阿夫拉洛创立的“永续时尚”初创企业深受名人青睐。2019年该公司声称其收益有望超过1.5亿美元。去年7月,阿夫拉洛向私募股权公司Permira Advisers出售了多数股权。她告诉《纽约时报》,她的公司很适合“既想拥有品牌和风格意识,又想做个好人的强大客户。”

但今年6月,就在Reformation在社交媒体上对“黑人的命也是命”运动表示支持后,圣地亚哥在Instagram上对她进行了猛烈抨击,声称阿夫拉洛觉得黑人雇员“很恶心”,并拒绝向他们提供Reformation白人员工拥有的职业机会,包括升职和旅行等。

一周后,阿夫拉洛道歉,并称其“辜负了大家”。之后,她辞去了CEO一职。(Reformation称,后来,第三方调查澄清了阿夫拉洛是“种族主义者”的说法,她留在了董事会。)

而由男性领导者领导的埃韦兰斯的结局则稍有不同。这也是一家风投支持的零售商,曾做出过“高透明度”的承诺。今年夏季,这家公司也因“放任反黑人言论和行为”遭遇了员工指控。6月,联合创始人兼CEO迈克尔•普雷斯曼在Instagram上承认自己“没能处理好公司内部的种族问题,和我们在该问题上向世人展示的态度。”

他依然任职CEO,三个月后,酩悦•轩尼诗-路易•威登集团(LVMH)旗下的私募股权巨头L Catterton向该公司注入了8500万美元新资本。

Pinterest创始人本•希伯尔曼以及Carta创始人亨利•沃德今年也遭遇了歧视指控,这也证明了依靠宣传公司的社会使命来进行营销的男性创始人也很容易遭遇伪善指控。

但和阿夫拉洛不同的是,他们并没有面临严重后果。

前Pinterest公共政策经理伊芙娜•欧佐玛称,“女性创业者百分之百会因为可怕的行为而遭到免职,但经营公司的男性却毫发无损,这真是太疯狂了。”伊芙娜曾因种族言论而遭到广泛报道,“如果本是一名女性的话,我无法想象她还能待在这里。”(一名Pinterset发言人表示,公司正对其文化展开独立审查。)

优步前CEO特拉维斯•卡兰尼克和WeWork前CEO亚当•纽曼最常反驳女性创业家更有可能被赶下台的说法。这两位都是在爆出不良行为期间被公司扫地出门的,但仅用了几个月或几年就摆脱了指控,还是在“有毒文化”和虐待员工范畴之外的情况下。

卡兰尼克的公司在2014年就遭到了监管和顾客投诉,但直到2017年,前员工苏珊•福勒爆料公司性骚扰猖獗的博客文章被疯传几个月后,他才辞去了CEO一职。而在WeWork中,已有内外部报道提及纽曼“花天酒地”的领导能力和培养“兄弟会文化”之事,但都没有起到作用。倒是停滞不前的首次公开募股(IPO)使得WeWork董事会终于在2019年9月把他赶下了台。(优步没有回应置评请求;WeWork拒绝评论。)

卡兰尼克和纽曼事件尖锐地指出,仅凭负面新闻报道和发酵的公众言论是无法解雇创始人的。归根结底,投资者,尤其是组成公司董事会的投资者,才掌握着决定创始人去留的生杀大权。

“董事会要履行义务和责任,”All Raise创始人科斯克特说道,“只不过标准不同。一旦发生了某些事,董事会会留给男性更多证据和时间。”

令事情更加复杂的是,创始人将股票出售给投资者后,还能保留多大控制权。卡兰尼克和纽曼从那些勉强同意“创始人友好”条件的投资者那里募资,在整个募资过程中掌握着公司控股权,但很少有女性能对上述条件提出要求。(去年一项研究表明,男性创始人每拥有一美元股本时,女性创始人平均只拥有48美分。)这意味着女性在筹集资本时遭遇的偏见,可能会在之后再次伤害她们,比如任凭董事会摆布她们。

对于多数目睹女性创业家辞职的人来说,真正的问题是,今后会发生什么。

投资者往往会给不怎么体面的男性创始人再度注资,比如卡兰尼克就为其新成立的风险企业CloudKitchens筹集了7亿多美元资本。相比之下,尽管在过去18个月内辞去CEO职位的女性再次以较低身份回到公司,却还没有任何一人升任要职。

而且没有人通过正式发言来表达得知自己正被严密审视时所感到的恐惧和脆弱。

“这种经历可不像‘掸掉裤子上的灰尘’这么简单。这是实打实的心理恐惧,”一位被迫离职的创始人说道。

虽然这位创始人还未透露其接下来的行动,但和其他在不利于自己的环境中打拼事业的女性一样,她称自己担心公众形象的坍塌会带来长远的影响。

如果投资人将女性领导者视为风险赌注的话,她们仅剩的一点资本也会弹尽粮绝。而且这对潜在的企业家本身也构成了影响。

“目睹这些是否会让想创业的女性感到巨大的阻碍呢?”这位创始人问道。“她们会一边看着这些女性,一边思考:‘如果这就是创业的代价,那我为何还要投身其中?’”(财富中文网)

本篇文章另一版本刊登于《财富》杂志2020年12月/2021年1月期,标题为“女性创业者备受攻击:聚光灯下的灼热。”

翻译:郝秀

审校:汪皓

编辑:徐晓彤

去年秋天,奥黛丽•格尔曼似乎登上了商界顶峰——至少也是为商界增添了一抹色彩。

32岁那年,这位来自纽约、人脉甚广的前政治活动家为the Wing募集了超过1.17亿美元的风险投资。The Wing是奥黛丽在2016年与同伴合作成立的高档女性俱乐部兼联合办公企业。

来自洛杉矶和伦敦等地的女性纷纷涌向the Wing色调柔和的办公室和众星云集的晚会。在这里,影视明星和总统候选人们谈论着“追求自己想要的”和“开辟自己的道路”等话题。

2019年9月,格尔曼登上了某期专门介绍女性创业者的《Inc.》杂志封面,庆祝事业和个人生活双丰收。

照片中的她怀孕八个月,气场全开。

“我希望所有女性都看到这个封面,鼓起信心面对更多职业风险,同时也不要放弃她们做母亲和组建家庭的梦想,”格尔曼在该封面发行当日的早晨对《今日秀》说道。

之后,事态走向了崩塌。一些黑人顾客在社交媒体和新闻中称,对the Wing和那里“白人居多”的场合感到不适。

今年三月,《纽约时报杂志》发表长篇报道,谈及the Wing内部员工口中的“有毒文化”,包括对钟点工收入和调度的投诉,以及对管理层不作为的抱怨等内容。例如,有一名顾客称黑色和棕色皮肤员工为“有色女孩”。

之后,the Wing的实体办公场所因新冠疫情关闭停摆,经营前景陷入困境。明尼阿波利斯市警方致乔治•弗洛伊德死亡事件又掀起了全国抵制种族歧视的热潮,放大了女性对the Wing的不满之声。她们声称the Wing未能践行其“姐妹情深”的女权主义说辞。一些在职和离职员工,包括很多疫情期间遭解雇的员工,均抵制该公司对“黑人的命也是命”运动做出的回应,并质疑格尔曼的领导能力。

六月中旬,顶着不断增加的压力和审视目光,格尔曼辞去了CEO一职。

“最终,公司的成长凌驾于文化之上,这是以牺牲有色女性获得力量的权利为代价的,”她在Instagram上写道,“我没能践行自己设立的价值观。”

格尔曼的瞬间失宠极具戏剧性,但并非个例。每当员工控诉管理不善或遭受虐待时,媒体通常会进行放大,每一位深陷其中的创始人都会在18个月内辞职或被迫离开公司。

运动服初创公司Outdoor Voices创始人泰勒•哈尼;箱包公司Away创始人斯蒂芬•科里;女性数字出版商Refinery29总编克莉丝汀•巴巴里克;制衣和服装品牌Reformation创始人雅艾尔•阿夫拉洛;零售品牌Ban.do创始人珍•高奇;工作场所福利平台Cleo创始人香农•斯帕哈克以及心理健康平台Crisis Text Line创始人南希•卢布林等女性,都遭遇了类似情况。

虽然每个人的卸任经历各有曲折,但这些公司和创始人有很多共同之处——这类公司都是快速成长型初创企业,强调女权主义或肩负着社会驱动使命。它们获得了风险资本的支持,或是已出售给了私有企业主。多数公司推出了面向消费者的产品。它们绝大多数都是由年轻富有的白人或亚裔创立的,且创始人已经成为了公司的“形象代言”。

对了,有人认为最重要的一点,是这些公司都是由女性成立的。

对于众多硅谷人士来说,业内多位杰出女性创始人的下台,这是令人不安的事情。

Winnie联合创始人兼CEO萨拉•莫斯科普夫称,“只有极少数女性能够真正得到媒体和众人的关注,但她们通常会在某一时刻黯然消失。”Winnie是一家成立于旧金山的儿童托育平台,已募集到1550万美元。

除此之外,其他一些女性创始人虽然掌管着公司,其管理风格和文化模式却面临着严苛的审视,包括皮肤护理初创企业Glossier、零售商Rent the Runway,交友应用软件Bumble和内衣公司ThirdLove的几名CEO。

很难不令人疑惑,正如莫斯科普夫说的那样:“到底怎么了?为什么只有女性出事?”

为了理解莫斯科普夫和其他24位接受《财富》杂志专访的创始人、投资者、高管和初创企业员工中多数人的担忧,应当从女性领导的初创企业现状着手,全局性地分析问题。

女性创始人的成功有迹可循。一项2018年波士顿咨询公司(BCG)的研究发现,女性创立的企业每投资一美元获取的收益是男性创立企业的两倍,但绝大多数投资者却会避开她们。2019年,初创企业获得的风险资本总额中,成员均为女性的创业团队仅获得了2.6%。2018和2019两年中,黑人女性获得的风投资金还不足0.3%。女性募集的资金数量仅为男性的三分之一左右,且不太可能在后续几轮中再次拿到资金。女性在公司中持有的股本较少,致使她们将更多的控制权让给了那些有权解雇或保护她们的投资者。

Crunchbase公司的数据显示,在价值超过10亿美元的“独角兽”初创企业中,只有4%是由女性创始人兼CEO经营的。这意味着,就比例来说,拥有创业资本支持的成功女性创始人甚至比《财富》500强女性CEO还罕见,而全美国7.4%的大型公司是由后者经营的。

显而易见,本次新冠疫情给女性创业者带来了经济灾难,使得本就困难的局面雪上加霜。

十月份,数据公司PitchBook报告称,第三季度女性创立企业获取的风投资金降至4.34亿美元,创三年来新低。同时期初创企业获得的投资总额378亿美元中,女性初创企业仅获得约1%。

投资者和企业家称,目前全球的不确定性又进一步强化了风险资本孤立和注重模式匹配的实质。在这些风险投资中,88%的投资决策者是男性,男性成立的公司被视为默认“安全”的赌注。

硅谷资深高管帕姆•科斯克塔称,“困难时期,一些人不过是回归到固有的模式识别上,他们的标准操作行为就是投给男性创始人。”科斯克塔目前经营着非盈利组织 All Raise,致力于女性风投和帮助女性创始人。

上述趋势,与一连串备受关注的女性创始人下台事件相结合,正引发一场初创企业业内人士愈演愈烈的讨论:女性创始人是否正遭到抵制,使得她们更容易受到公众的监督,最终导致,与男性同僚相比,她们被迫离开公司的可能性更大。

The Coven是一家位于明尼阿波利斯市的女性联合办公初创企业。其联合创始人兼CEO亚历克斯•韦斯特•斯坦曼称,“显然,女性面临着双重标准,”大量社会学研究和随处可见的现实经验也证明,“我们无论何时都背负着目标,但人们总希望我们失败。”

商界女性面临着所谓的“双重束缚”,她们会因“不像女人”的行为而受到谴责,但这些行为在男性领导身上却是值得期待和赞赏的。2007年,纽约大学研究人员领导的一项研究发现,当使用同样的人格特征描述两名性别相异的管理人员时,“女性显然更不讨喜”且“更易被视为不受欢迎的老板。”男女领导拥有同样行为时,男性总是被视为是坚强、坚决和果断的,而女性则被认为是激进、粗暴或无理取闹的。

不过,也不是每个人都认为初创企业中存在的性别歧视。

“创业者很难做,但竞争环境还是相对公平的,”31岁的亚历克莎•冯•托贝尔说道。她将自己的金融规划服务初创公司LearnVest卖给了西北互助人寿保险公司(Northwestern Mutual)。目前,亚历克莎正经营着刚成立不久的风险投资公司Inspired Capital。

对于莫斯科普夫所提出的商界的失势“只会发生在女性身上” 这种说法,亚历克莎持反对意见,并举例比如令人震惊的WeWork联合创始人亚当•诺依曼和优步(Uber)联合创始人特拉维斯•卡兰尼克下台事件,以及最近发生的尼古拉(Nikola)创始人特雷弗•米尔顿辞职事件。

同时,今年有几家公司的员工在新闻媒体、社交媒体和几场诉讼案中,就男性创始人兼CEO的领导能力和职场文化问题也进行了投诉。这些公司包括社交网站Pinterset,服饰品牌埃韦兰斯(Everlane)和股权服务公司Carta(至少到目前为止,这几名创始人仍然在职)。

保险科技公司Policygenius联合创始人兼CEO詹妮弗•菲茨杰拉德称,“面试时,人们首先提及的就是文化,”她的保险公司已从私人投资者处筹资超过1.62亿美元。她表示,当员工在社交媒体或新闻中苛责CEO时,“与其说是性别问题,不如说是人们脾气变得更加暴躁、平台变大以及员工的容忍度降低了。”

现实情况可能更微妙些,但并不意外。在许多此类事件中,值得询问的是,这些女性创始人是否本身也设置了陷阱,让自己往里跳。

例如,Outdoor Voices创始人泰勒•哈尼于2014年成立了在Instagram上颇受欢迎的运动服饰公司,并于五年内筹资超过6000万美元。她似乎走着和格尔曼相同的路线:在众多杂志封面上亮相;2019《纽约客》刊登了她的大篇幅介绍,将她评为“最佳品牌典范”;在七月的《早安美国》节目中,她宣布自己怀孕了,并激励女权主义者;“作为一名年轻的女性创始人兼CEO,你不必在事业和家庭间做选择,这真是太棒了。”

但今年2月,还在休产假的哈尼透露她正准备离开公司。不久后,有报道称,在她的监管下,Outdoor Voices不仅烧钱、延迟门店开张,还失去了富有经验的高管。员工向BuzzFeed新闻匿名投诉,声称虽然跟着号称“鼓舞人心”的年轻女性创始人工作,却发现哈尼引领着一种不正常的偏袒文化。

哈尼在Outdoor Voices的地位降低了。她在接受《Inc.》杂志采访时承认,该品牌“在适当的情况下确实会抛出【女创始人】的故事......我们就是靠这个来发展品牌的,而且我们成了新闻媒体的宠儿。但直到它失效前,一切都很好,因为我们也成为了新闻媒体重点关注的对象。”

正如哈尼和格尔曼一样,许多离职或最近备受指责的女企业家们似乎都在走同一条路——创立以消费者为导向的品牌,并使自己成为公司的公众面孔。如果创立的品牌出售的是打底裤,而非云计算公司的软件,这种模式就更常见了。

Acrew Capital创始合伙人特蕾莎•格武称这类企业“更受新闻媒体青睐,因为更适合一般读者,这是两全其美的。”虽然确有女性成立高端技术公司,但也只是少数。

PitchBook和All Raise数据显示,去年,零售和消费类公司风险投资金额中,有30%流向了至少由一位女性创始人设立的初创企业。但在科技初创企业中,该份额降至19%。

零售/消费领域人满为患,因此,抱着将创始人当成明星的想法,并采用宣扬女权主义崛起的营销方式,一直是由女性领导的初创企业应对质疑的方法。但这也公然将女性创始人与公司的失败联系在了一起,尤其体现在承诺为代表性不足的顾客发声,和为雇员创造更良好空间方面。

“在女权主义基础上建立独角兽规模的公司,这个领域是很难涉足的。一旦看上去不够真诚,那就很危险了,”连续创业家凯瑟琳•康纳斯说道。她现在是网络创业公司League of Badass Women的CEO。

几位企业家告诉我,这种视创始人为中心、打着“女性创业为女性”旗号的营销方式,经常是受到初创企业风险投资方的“指令”,投资者迫使创业者选择将其创业公司打造成“女性生活方式”企业,否则就得不到融资。

“我们是粉红投资组合,”康纳斯说道。“我们假定,利用女权主义和女性客户保证盈利,在公司的估值达到10亿美元的时候,我们就可以套现离场。”

莫斯科普夫称,就在她和她的女性联合创始人为其软件平台集资时,一位潜在投资人问她们为何“不经常上新闻”,以及她们是否能尝试“创立一个类似TheSkimm的品牌”。 TheSkimm是一家媒体公司,除了创始人也是两位女性以外,和Winnie几乎没有共同点。“我们只希望人们能使用Winnie,”莫斯科普夫说。“顾客不需要考虑我和我的联合创始人。”

这就要谈到科技行业和媒体之间的爱恨情仇了。

很多创业生态系统内部人士斥责道,记者“打造”出年轻美丽的女性创始人,只是为了最后毁掉她们。这些女性的崛起的确在一定程度上得益于包括《财富》杂志在内的商业出版物,和主要报道商业女性的女记者,比如我。(在加入《财富》杂志前,我为《Inc.》编辑了与格尔曼封面孕肚照相关的女性创始人系列章节)。我们也有责任报道这些公司的失败,但当掌权者是一位女性时,这类报道常会遭到口诛笔伐,说我们带有偏见或是骗点击量。

资金跌落

2020年第三季度女性创立企业获取的风投资金降至4.34亿美元,创三年来新低。

由创始人性别决定的美国风投交易流

2019年12月,科技媒体the Verge报道Away CEO斯蒂芬•科里深夜向员工发送言辞激烈、带有“侮辱性”的Slack信息,并希望员工取消假期回来加班。报道刊登后,科里暂时辞职。今年夏天她在Instagram上强烈反抗:“我不并想说究竟发生了什么,只想在社交媒体上写点东西给大家看,”她写道。“为何总针对女性?因为读者看她们登高跌重的故事看得津津有味。”

科里于今年1月重新担任公司的联合CEO,而后又于10月再次辞职,她拒绝评论此事。但许多初创企业业内人士则声称,男性领导人做出类似或更糟糕的行为时,却往往能侥幸逃脱。(详见《财富》2020年度商业人物埃隆•马斯克。)

“成长期的公司并不适合所有人,这是个不可告人的秘密。很多这类公司的文化都有问题,” Female Founders Alliance创始人莱斯莉•芬扎格说道。

相反,很少有女性能确保募集到大量风投资金,无论她们是否愿意这么想,她们都无可避免地被推上了All Raise科斯克塔口中的“完美基座”上,受到媒体、员工和投资者的密切注视。众目睽睽之下,她们本能地害怕自己变成下一个倒霉蛋。

“每次有人倒下,我就会收到女性创业者发来的信息,写的都是,‘什么鬼东西?’以及,‘何时会轮到我?’等等”风险投资公司NEA合伙人瓦妮莎•拉克说道,“这太可怕了,根本不公平。”

甚至一些把创始人投诉至辞职的初创公司员工也承认,他们对女性创始人有更多的诉求。部分原因在于,少数登上“完美基座”的女性通常是享有特权的白人,她们经常承诺,企业终将为黑皮肤和棕色皮肤的钟点工提供更好的机会。

“女性肩负着更沉重的责任。在男性主导的社会中,这就是女性要面对的。”莱斯利安•艾力•圣地亚哥说道。她是一名波多黎各黑人,也是Reformation的前商店经理助理,“但创立并非只为白人女性服务的企业,也是她们的职责”。

2020年反种族主义抗议不仅加剧了对女性创业者的强烈抵制,也让人们更清楚地看到性别双重标准的真容。

直接对比男性和女性领导的公司不易得出结论,不过Reformation的案例却很相近。这家由前模特雅艾尔•阿夫拉洛创立的“永续时尚”初创企业深受名人青睐。2019年该公司声称其收益有望超过1.5亿美元。去年7月,阿夫拉洛向私募股权公司Permira Advisers出售了多数股权。她告诉《纽约时报》,她的公司很适合“既想拥有品牌和风格意识,又想做个好人的强大客户。”

但今年6月,就在Reformation在社交媒体上对“黑人的命也是命”运动表示支持后,圣地亚哥在Instagram上对她进行了猛烈抨击,声称阿夫拉洛觉得黑人雇员“很恶心”,并拒绝向他们提供Reformation白人员工拥有的职业机会,包括升职和旅行等。

一周后,阿夫拉洛道歉,并称其“辜负了大家”。之后,她辞去了CEO一职。(Reformation称,后来,第三方调查澄清了阿夫拉洛是“种族主义者”的说法,她留在了董事会。)

而由男性领导者领导的埃韦兰斯的结局则稍有不同。这也是一家风投支持的零售商,曾做出过“高透明度”的承诺。今年夏季,这家公司也因“放任反黑人言论和行为”遭遇了员工指控。6月,联合创始人兼CEO迈克尔•普雷斯曼在Instagram上承认自己“没能处理好公司内部的种族问题,和我们在该问题上向世人展示的态度。”

他依然任职CEO,三个月后,酩悦•轩尼诗-路易•威登集团(LVMH)旗下的私募股权巨头L Catterton向该公司注入了8500万美元新资本。

Pinterest创始人本•希伯尔曼以及Carta创始人亨利•沃德今年也遭遇了歧视指控,这也证明了依靠宣传公司的社会使命来进行营销的男性创始人也很容易遭遇伪善指控。

但和阿夫拉洛不同的是,他们并没有面临严重后果。

前Pinterest公共政策经理伊芙娜•欧佐玛称,“女性创业者百分之百会因为可怕的行为而遭到免职,但经营公司的男性却毫发无损,这真是太疯狂了。”伊芙娜曾因种族言论而遭到广泛报道,“如果本是一名女性的话,我无法想象她还能待在这里。”(一名Pinterset发言人表示,公司正对其文化展开独立审查。)

优步前CEO特拉维斯•卡兰尼克和WeWork前CEO亚当•纽曼最常反驳女性创业家更有可能被赶下台的说法。这两位都是在爆出不良行为期间被公司扫地出门的,但仅用了几个月或几年就摆脱了指控,还是在“有毒文化”和虐待员工范畴之外的情况下。

卡兰尼克的公司在2014年就遭到了监管和顾客投诉,但直到2017年,前员工苏珊•福勒爆料公司性骚扰猖獗的博客文章被疯传几个月后,他才辞去了CEO一职。而在WeWork中,已有内外部报道提及纽曼“花天酒地”的领导能力和培养“兄弟会文化”之事,但都没有起到作用。倒是停滞不前的首次公开募股(IPO)使得WeWork董事会终于在2019年9月把他赶下了台。(优步没有回应置评请求;WeWork拒绝评论。)

卡兰尼克和纽曼事件尖锐地指出,仅凭负面新闻报道和发酵的公众言论是无法解雇创始人的。归根结底,投资者,尤其是组成公司董事会的投资者,才掌握着决定创始人去留的生杀大权。

“董事会要履行义务和责任,”All Raise创始人科斯克特说道,“只不过标准不同。一旦发生了某些事,董事会会留给男性更多证据和时间。”

令事情更加复杂的是,创始人将股票出售给投资者后,还能保留多大控制权。卡兰尼克和纽曼从那些勉强同意“创始人友好”条件的投资者那里募资,在整个募资过程中掌握着公司控股权,但很少有女性能对上述条件提出要求。(去年一项研究表明,男性创始人每拥有一美元股本时,女性创始人平均只拥有48美分。)这意味着女性在筹集资本时遭遇的偏见,可能会在之后再次伤害她们,比如任凭董事会摆布她们。

对于多数目睹女性创业家辞职的人来说,真正的问题是,今后会发生什么。

投资者往往会给不怎么体面的男性创始人再度注资,比如卡兰尼克就为其新成立的风险企业CloudKitchens筹集了7亿多美元资本。相比之下,尽管在过去18个月内辞去CEO职位的女性再次以较低身份回到公司,却还没有任何一人升任要职。

而且没有人通过正式发言来表达得知自己正被严密审视时所感到的恐惧和脆弱。

“这种经历可不像‘掸掉裤子上的灰尘’这么简单。这是实打实的心理恐惧,”一位被迫离职的创始人说道。

虽然这位创始人还未透露其接下来的行动,但和其他在不利于自己的环境中打拼事业的女性一样,她称自己担心公众形象的坍塌会带来长远的影响。

如果投资人将女性领导者视为风险赌注的话,她们仅剩的一点资本也会弹尽粮绝。而且这对潜在的企业家本身也构成了影响。

“目睹这些是否会让想创业的女性感到巨大的阻碍呢?”这位创始人问道。“她们会一边看着这些女性,一边思考:‘如果这就是创业的代价,那我为何还要投身其中?’”(财富中文网)

本篇文章另一版本刊登于《财富》杂志2020年12月/2021年1月期,标题为“女性创业者备受攻击:聚光灯下的灼热。”

翻译:郝秀

审校:汪皓

编辑:徐晓彤

Last fall, Audrey Gelman seemed to be on top of the business world—or at least one pale-pink corner of it. At 32 years old, the former political operative and well-connected New Yorker had raised more than $117 million in venture capital for the Wing, the upscale women’s club and coworking startup she had cofounded in 2016. Women from Los Angeles to London flocked to the Wing’s pastel-painted offices and star-studded events, where movie stars and presidential candidates alike talked about “asking for what you want” and “blazing your own trail.”

By September 2019, Gelman was celebrating her professional and personal triumphs by appearing, eight months pregnant and unquestionably powerful, on the cover of an issue of Inc. magazine devoted to female startup founders. “My hope is that women see this and feel the confidence to take greater professional risks, while also not shelving their dreams of becoming a mother and starting a family,” she told the Today show on the morning that the cover was released.

Then it started to crumble. Some Black customers were already sharing on social media and in the press the discomfort they sometimes felt at the Wing and its “majority-white” space. And in March, The New York Times Magazine published a long feature about what employees called the Wing’s “toxic culture,” including complaints about pay and scheduling for hourly workers and Wing managers’ poor handling of incidents, such as one in which a customer referred to Black and brown employees as “colored girls.” Then, as COVID-19 shut down the Wing’s physical locations and threw its business future into question, George Floyd’s killing by Minneapolis police sparked a national reckoning over racism—amplifying the voices of women who said the Wing had failed to live up to its feminist rhetoric of sisterhood for all. Current and former workers, including many laid off amid the pandemic, protested the company’s attempted response to the Black Lives Matter movement and Gelman’s leadership.

By mid-June, amid mounting pressure and scrutiny, Gelman stepped down as CEO. “Ultimately the prioritization of growth over culture came at the expense of women of color feeling empowered,” she later wrote on Instagram. “I didn’t live up to the values I set."

Gelman’s fall from grace was dramatic—but not singular. Amid employee allegations of mismanagement or mistreatment—often amplified by the press—each of these founders has stepped down or been forced out of her company in the past 18 months: Tyler Haney of activewear startup Outdoor Voices; Steph Korey of luggage company Away; Christene Barberich of women’s digital publication Refinery29; Yael Aflalo of dressmaker and fashion brand Reformation; Jen Gotch of retailer Ban.do; Shannon Spanhake of workplace-benefits platform Cleo; and Nancy Lublin of mental-health platform Crisis Text Line.

While each ouster has its own twists and turns, there’s a lot that unites these companies and founders. All are fast-growing startups that emphasized feminist or socially driven missions. All have venture capital backing or have been sold to private owners. Most provide consumer-facing products. The vast majority were started by young, wealthy, white, or Asian founders who had become the celebrity faces of their businesses. And—some would argue, most crucially—all were founded by women.

To many in Silicon Valley, the toppling of so many of the industry’s most prominent female founders signals something much bigger and more disconcerting than the usual game of startup musical chairs. “There are very few women leaders who rise to the level where they get press and attention, and at some point, they’re all disappearing,” says Sara Mauskopf, the cofounder and CEO of Winnie, a San Francisco-based childcare platform that has raised $15.5 million. Throw in a slew of other female founders who remain atop their companies but who have faced pointed scrutiny of their management styles and cultures—including the CEOs of skin care startup Glossier, retailer Rent the Runway, dating app Bumble, and lingerie company ThirdLove—and it’s hard not to wonder, as Mauskopf does: “What the heck is going on? And why is this only happening to women?”

******

To understand the alarm expressed by Mauskopf and many of the 24 other founders, investors, executives, and startup employees who spoke to Fortune for this story, it helps to start with a big-picture view of the state of women-led startups. Female founders have a track record of success—one 2018 BCG study found that women-owned businesses earn twice as much revenue per dollar invested as male-owned businesses do—but the overwhelming majority of investors shun them. Women-only founding teams received only 2.6% of all venture capital invested in startups in 2019, with Black women receiving less than 0.3% of VC in 2018 and 2019. Women who do get funding raise about a third of the amount that men do, on average, and are less likely to raise subsequent rounds. They also retain less equity in their companies, thus ceding more control to the investors who have the power to fire or protect them.

Female founder-CEOs run only 4% of the “unicorn” startups valued at more than $1 billion, according to Crunchbase. Which means that, proportionally, these successful venture-backed female founders are even more rare than female Fortune 500 CEOs, who currently run 7.4% of the country’s largest companies.

The pandemic, which has created an economic catastrophe for women writ large, has made this challenging situation still more difficult. In October, data firm PitchBook reported that VC funding for companies founded by women dropped to $434 million in the third quarter, its lowest level in three years—and about 1% of the $37.8 billion invested in all startups during the same period.

Investors and entrepreneurs say the current global uncertainty has reinforced the insular, pattern-matching nature of venture capital, in which 88% of those making investing decisions are male and male-founded companies are seen as the default “safe” bet. “In a time of stress, there are people who are just falling back to pattern recognition and their standard operating behavior” of investing in male founders, says Pam Kostka, a veteran Silicon Valley executive who now runs All Raise, a nonprofit devoted to female VCs and founders.

These trends, married with the cascade of high-profile founder ousters, are fueling a growing debate among startup industry insiders over whether female founders are facing a backlash—one that makes them more subject to public scrutiny and, ultimately, more likely to be forced out of their companies than their male counterparts.

“There’s absolutely a double standard for women,” says Alex West Steinman, the cofounder and CEO of the Coven, a ¬Minneapolis-based women’s coworking startup. “We do walk around with a target on our backs, and people are looking for us to fail.” There’s copious social science research—and widespread real-world experience—that agrees. Women in the business world face what’s been dubbed the “double bind,” which penalizes them for “unfeminine” behaviors that are expected and often applauded in male leaders. One 2007 study led by a New York University researcher found that when two managers were described using identical personality traits but different genders, “women are decidedly more disliked” and “are found to be less desirable as bosses.” Where male leaders are seen as strong, determined, and decisive, women who behave the same way are judged to be aggressive, abrasive, or strident.

Still, not everyone sees a gender backlash at startups. “Being a founder is so hard, but the playing field felt relatively fair,” says Alexa von Tobel, who at age 31 sold her financial planning startup, LearnVest, to Northwestern Mutual and who now runs her own early stage venture capital firm, Inspired Capital. Naysayers dispute the idea that, as Mauskopf put it, such falls from grace “happen only to women,” pointing to the high-profile exits of WeWork cofounder Adam Neumann and Uber cofounder Travis Kalanick, and the more recent departure of Nikola founder Trevor Milton. Meanwhile, employees have complained this year in the press, on social media, and in a couple of lawsuits about the leadership of and workplace cultures created by the male founder-CEOs of companies including Pinterest, Everlane, and Carta (all of whom have, at least thus far, retained their jobs).

“Culture is top of mind for anybody interviewing now,” says Jennifer Fitzgerald, the cofounder and CEO of Policygenius, whose insurance company has raised more than $162 million from private investors. She argues that when workers criticize CEOs on social media or in the press, it’s “less of a gender thing and more that there’s just a shorter fuse and a bigger public platform, and a lower tolerance for it among employees.”

******

The reality of the situation may—not surprisingly—be a little more nuanced. In many of these cases, it’s worth asking whether the female founder in question helped set the very traps she walked into. Outdoor Voices founder Tyler Haney, for example, started her Instagram-friendly activewear company in 2014 and within five years raised more than $60 million. She seems to have been reading from the same playbook as Gelman, sitting for multiple magazine covers, participating in a long 2019 New Yorker profile that anointed her the “brand’s best model,” and announcing her pregnancy that July on Good Morning America with her own message of feminist empowerment: “As a young female founder and CEO, it’s so cool to show that you don’t have to choose career or family.”

But in February, while still on maternity leave, Haney revealed she was leaving the company. Soon after came the reports that under her watch, Outdoor Voices had been burning through cash, delaying store openings, and losing seasoned executives. Employees complained, anonymously, to BuzzFeed News that having come to work for a young female founder one called “so inspiring,” they instead found Haney presiding over a dysfunctional culture of favoritism.

Haney, who returned to a diminished role at Outdoor Voices, has acknowledged in an interview with Inc. that the brand “definitely pulled that [female founder] narrative out when it suited us … We really leaned into that story to grow this thing, and we became press darlings. But that’s all great until it’s not, because we also made ourselves targets.”

Like Haney and Gelman, many of the female entrepreneurs who have resigned or come under criticism recently founded consumer-oriented brands and became the very public faces of their companies in a way that’s more common if you’re selling leggings than, say, cloud-based enterprise software. These businesses often “get more press, because they’re more relatable to the general reader,” says Theresia Gouw, founding partner of Acrew Capital. “That can cut both ways.” And while there are certainly women who start hard-tech companies, they are in the minority: Last year, 30% of the VC investments in retail and consumer companies went to startups with at least one female founder, according to data from PitchBook and All Raise. Among tech startups, that share drops to 19%.

The retail/consumer space is a crowded one, so embracing the idea of founder as star and adopting a marketing message that preaches feminist uplift has been one way for women-led startups to cut through the noise. But it also publicly ties female founders to their companies’ failings, especially around promises of creating better spaces for underrepresented customers and employees. “It’s a very, very difficult territory to walk, to build a unicorn-scale business based on feminism. To be seen as inauthentic around that is dangerous,” says Catherine Connors, a serial entrepreneur who's currently the CEO of the League of Badass Women, a networking startup.

Several entrepreneurs told me that this sort of founder-centric, by-women-for-women marketing is often a mandate from the VCs who invest in startups—forcing founders to choose between pitching their startups as another girly lifestyle business or not getting funding at all. “We’re the pink portfolio,” Connors says. “The assumption is that we’ll use femininity and access to the female customer for the bottom line—and to get to the $1 billion exit.”

Mauskopf says that while she and her female cofounder were raising money for their software platform, one potential investor asked why they “weren’t out there in the press more” and asked if they could try “to build a brand like TheSkimm”—a media company with little in common with Winnie, aside from its being founded by two women. “We just need people to use Winnie,” Mauskopf says. “They don’t need to care about me or my cofounder.”

Which brings us to the tech industry’s love/hate relationship with the press. Many in the startup ecosystem blame reporters for building up young, photogenic female founders only to eventually tear them down. And it’s true that the rise of these women has been partially enabled by business publications including Fortune and by the largely female journalists who cover women in business, including me. (Before joining Fortune, I edited the Inc. package on female founders tied to Gelman’s pregnant cover photo.) It’s also our responsibility to report on the failings of these companies—but when a woman is in charge, such reporting often draws accusations of bias or clickbait.

)

In December 2019, after the Verge reported on intense and “bullying” Slack messages that Away CEO Steph Korey sent to employees late at night and her expectations that they cancel holiday vacations to work, Korey briefly stepped down. This summer she hit back on Instagram: “The incentive isn’t to report what’s happening. It’s to write things that will be shared on social media,” she wrote. “Why are women being targeted specifically? Because readers find their takedowns even juicier."

Korey, who in January returned as co-CEO and in October stepped back again, declined to comment. But many startup insiders argue that male leaders get away with similar demanding behavior—or worse—all the time. (See also Elon Musk, Fortune’s 2020 Businessperson of the Year.) “The dirty secret is that being in a growth-stage company, it’s not for everyone. And a lot of these companies have problematic cultures,” says Leslie Feinzaig, founder of the Female Founders Alliance, a startup community.

Instead, the rare women who secure significant VC money—whether they opt to lean in to the idea or not—are inevitably put on what All Raise’s Kostka calls “the perfection pedestal,” closely scrutinized by media, workers, and investors. With that spotlight comes the visceral fear that they could be next.

“Every time there’s a teardown, I get text messages from female founders that are just like, ‘What the hell?’ And, ‘When is it going to be me?’” says Vanessa Larco, a partner at venture capital firm NEA. “It’s scary—and it’s just not fair."

Even some of the startup employees whose complaints have led to founder resignations acknowledge that they expect more from female founders—in part because the few who do reach the “perfection pedestal” tend to be privileged white women who often promise that their business will be the one to finally provide better opportunities to the Black and brown hourly workers they employ.

“Women are a lot more harshly held accountable. That’s part of being a woman in a male-dominated society,” says Leslieann Elle Santiago, a former assistant store manager at Reformation who is a Black-identifying Puerto Rican. “But they have a responsibility to create businesses that are not only for white women."

The anti-racist reckoning of 2020 has both accelerated the female founder backlash and provided more of a window into how the gender double standard plays out. Direct comparisons between male- and female-led companies aren’t easy to make, but the case of Reformation comes close. Founded by former model Yael Aflalo, the “sustainable fashion” startup is a celebrity favorite that in 2019 claimed it was on track to post more than $150 million in revenue. Last July, Aflalo sold a majority stake to private equity firm Permira Advisers, telling the New York Times that her company catered to “a powerful customer who wants to be both brand- and style-conscious but also be a good person.”

But in June, after Reformation expressed social media support for Black Lives Matter, Santiago responded fiercely on Instagram, alleging that Aflalo had treated Black employees with “disgust” and denied them professional opportunities, including promotions and travel, that were offered to white Reformation employees. A week later, after Aflalo apologized and said she had “failed all of you,” she resigned as CEO. (Reformation says a third-party investigation later cleared Aflalo of being “racist”; she remains on the board.)

The outcome was a bit different at Everlane, another venture-backed retailer that promises “radical transparency” and that this summer also faced employee allegations that it had allowed anti-Black language and behavior. In June, cofounder and CEO Michael Preysman acknowledged on Instagram that he had “fallen short of addressing issues of institutional racism both inside the company and in how we present ourselves to the world.” He remained CEO and, three months later, LVMH-backed private equity giant L Catterton led a new $85 million investment in the company.

Preysman—like Pinterest’s Ben Silbermann and Carta’s Henry Ward, both of whom have also weathered allegations of discrimination this year—is proof that male founders who rely on marketing that touts their companies’ social missions are also vulnerable to damaging charges of hypocrisy. But unlike Aflalo, none faced significant consequences.

“Female founders 100% deserve to be removed from their posts for horrific behavior, but the fact that there are no repercussions for men who are running these companies is crazy,” says Ifeoma Ozoma, a former Pinterest public policy manager whose claims of racism have been widely reported. “I can’t imagine a situation where a woman in Ben’s position would still be there.” (A Pinterest spokesperson says the company is conducting an independent review of its culture.)

The two men most often trotted out to refute claims that women founders are more likely to be ousted are former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick and former WeWork CEO Adam Neumann. Both were pushed out of their companies in the midst of reports of bad behavior, but only after months or years of being able to shrug off the allegations—and amid circumstances that went beyond claims of “toxic culture” or employee mistreatment. Kalanick, whose company was the subject of well-chronicled regulatory and customer complaints by 2014, didn’t step down as CEO until 2017, months after former employee Susan Fowler’s blog post about the company’s rampant sexual harassment went viral. At WeWork, a stalled IPO did what internal and external reports of Neumann’s hard-partying leadership and fostering of a “frat-boy culture” couldn’t, and WeWork’s board finally pushed him out in September 2019. (Uber did not respond to a request for comment; WeWork declined to comment.)

The cases of Kalanick and Neumann are a harsh reminder that it takes more than some bad press and a soured public opinion to fire a founder. Ultimately, the most power to purge or protect lies with investors, especially those who make up the company’s board of directors. “Boards do have an accountability and a responsibility here,” says All Raise’s Kostka. “There’s just a different standard. When something does happen, it seems like they will allow more evidence and more time for a man.”

Further complicating the issue is the question of how much control a founder has managed to retain after selling stakes to investors. Both Kalanick and Neumann maintained controlling stakes in their companies throughout fundraising, from investors willing to grant “founder-friendly” terms that few women say they feel able to ask for. (According to a study last year, the average female founder owns 48¢ in equity for every dollar owned by a male founder.) That means the bias women face while raising money¬ can come back to bite them later by placing them at the mercy of their board.

For many of those watching the female-founder shakeout, the real question is what comes next. Investors have a long history of giving disgraced men—including Kalanick, who has raised more than $700 million for his new venture, CloudKitchens—another shot. But while some of the women who have left their CEO roles in the past 18 months have rejoined their companies in some less influential form, none have yet moved on to their next big thing.

And none would speak on the record, expressing fear and fragility about how closely they now know they’re being watched. “This is not just a ‘dust off your pants’ experience. It’s really psychologically scarring,” says one founder who was forced to resign from her company.

While this founder wasn’t ready to discuss her next move, she, like many of the other women who have spent their careers trying to navigate a system stacked against them, says she’s worried about the long-term implications of her public downfall. If women leaders come to be seen as a risky bet for funders, what little money is going their way could dry up. And then there’s the effect on would-be entrepreneurs themselves.

“Is watching all of this go down this ¬massive deterrent for women to start companies?” this founder asks. “They’re watching all these other women and wondering: ‘If that’s the price of admission, why do I want to do it?’”

A version of this article appears in the December 2020/January 2021 issue of Fortune with the headline, "Female founders under fire: It's hot in the spotlight."