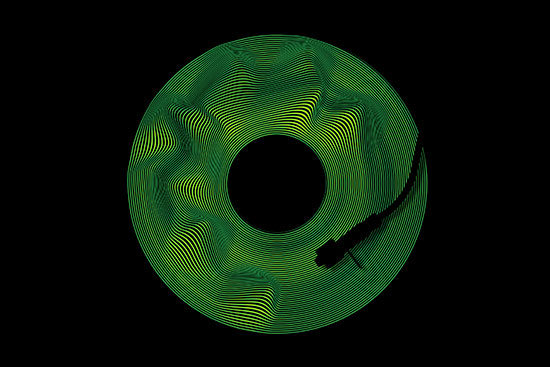

这家公司拯救了音乐行业,现在要拯救自己了

|

谁能想像泰勒·斯威夫特也犯过错误?这位乡村流行音乐界的女王在2014年突然公开宣布与其知名的追求者Spotify分手,此举让粉丝震惊不已。就在10月新专辑《1989》发布数天之后,斯威夫特从这家领先的音乐流媒体服务下架了其所有歌单,并用有说服力的证据解释了为什么Spotify会威胁音乐行业的发展。 斯威夫特当时在抨击Spotify所谓的免费商业模式时说:“我个人觉得这个实验性项目没有给词作者、制作人、艺人以及作曲人支付公允的报酬,我不愿意把我毕生的心血交给它,而且它们宣传的理念是:音乐没有价值,应该是免费的,对此我真的无法赞同。” 斯威夫特的决绝赢得了全球唱片艺人的赞许,他们认为流媒体音乐服务正在蚕食其已然微薄的收益。毕竟,由于CD销量的断崖式下跌,唱片行业的营收在近15年来一直处于下滑状态。Spotify的联合创始人兼首席执行官丹尼尔·艾克发布了一篇长文来捍卫其公司。(他写道:“最近所有有关Spotify靠剥削艺人来赚钱的传言让我感到愤怒不已。”)但从销量来看,斯威夫特的举措被证明是一场胜利。在获选成为公告牌(Billboard)年度收入最高的音乐艺人之后,尽管没有Spotify服务器的帮助,但斯威夫特的专辑连续三周的周销量都达到了100万张。尼尔森音乐称,这是历史上首位获此成就的唱片艺人。 斯威夫特对Spotify:1比0。 然而,尽管泰勒一时之间风光无限,但Spotify从长期来看并没有遭受多少损失。事实上,2014年是音乐销售的低谷,也是Spotify引领的音乐流媒体崛起的开端。 自斯威夫特脱离Spotify的那一年起,全球唱片业的整体销量逐年递增,从2014年的143亿美元增至2018年的181亿美元。国际唱片业联合会(IFPI)称,这主要归功于付费流媒体服务。如今,付费和植入广告的流服务共计贡献了半数的全球唱片业营收。(实物CD和唱片的销售量依然贡献着25%的营收;其余的则来自于其他营收,例如演出权。)英国市场研究公司Midia估计,Spotify在流媒体服务行业处于领先地位,占据着三分之一强的流媒体市场,其月用户达到了2.32亿,全球付费注册会员为1.08亿。 即便是斯威夫特也在为Spotify带来收益的同时收获了听众的赞誉。如今,斯威夫特《Shake It Off》整张专辑的曲目均可以通过该应用程序收听,包括专辑《1989》和最新专辑《Lover》。 Spotify和艾克从其平台的崛起获益良多。艾克与马丁·洛伦宗于2006年在斯德哥尔摩共同创建了Spotify,并于2018年4月通过直接挂牌(而不是传统的首次公开募股)的形式让公司上市。如今,Spotify的市值约为210亿美元,而艾克自己的净财富值接近20亿美元。分析师估计,公司2019年的销售额将达到70亿美元。波士顿咨询公司(BCG)称,Spotify的整体前景异常强劲,它在今年的《财富》全球未来50强榜单中名列第五位,上榜者均为在实现长期增长方面有着最佳优势的公司。 但没有人可以保证Spotify能够一直在该榜单中名列前茅。受音频流业务增长的激励,科技巨头苹果和亚马逊也杀入了这一市场,而且这两家都是财大气粗的主,更何况它们都有着各自的优势——iPhone和Echo音箱,众多听众都通过这两款设备来收听音乐。与此同时,美国、英国等国主流音乐流媒体市场的成熟也在迫使Spotify和其竞争对手在巴西、墨西哥、印度以及德国和日本等“后来者”市场争夺新兴机遇。 Spotify早已发现,盈利实非易事。在2018年第三和第四季度首次出现季度盈利之后,公司在今年上半年再次出现亏损,也让一些投资者对其股票失去了信心。自Spotify上市以来,其股价下跌了30%,而纳斯达克则上涨了15%。Spotify费尽唇舌与主流唱片公司(该服务提供的大部分流媒体音乐都来自于环球、索尼和华纳,以及独立机构Merlin的授权)达成的协议也没有给自身利润率的提升预留多大的空间。 Spotify是音乐行业的救星。如今,该公司需要证明自己并非只是昙花一现。 |

Imagine, for a moment, that Taylor Swift was wrong. The reigning queen of country-tinged pop shocked fans in 2014 by abruptly and publicly breaking up with a prominent suitor: Spotify. Mere days after the October release of her album 1989, Swift yanked her entire back catalog from the leading music-streaming service—and made a compelling case why Spotify was a threat to her industry. “I’m not willing to contribute my life’s work to an experiment that I don’t feel fairly compensates the writers, producers, artists, and creators of this music,” Swift said at the time, taking a swipe at Spotify’s so-called freemium business model. “And I just don’t agree with perpetuating the perception that music has no value and should be free.” Swift’s bold move won her acclaim from recording artists around the world who believed that streaming music services were cutting into their already meager bottom lines. After all, revenues for recorded music had been falling for a decade and a half thanks to plummeting CD sales. Spotify cofounder and CEO Daniel Ek countered by publishing a lengthy essay defending his company. (“All the talk swirling around lately about how Spotify is making money on the backs of artists upsets me big-time,” he wrote.) And Swift’s scheme proved to be a triumph once the receipts rolled in. Named America’s highest-earning musician that year by Billboard, Swift went on to sell a million copies a week of her album for three weeks straight—the first such recording artist to do so, according to Nielsen SoundScan—without the work ever landing on Spotify servers. Swift 1, Spotify 0. But while Taylor may have won the day, Spotify hardly suffered in the long run. In fact, 2014 was the low point for music sales—and the start of a resurgence for the business, led by Spotify. Since the year of Swift’s Spotify defection, the global recorded music industry has seen overall sales grow every year—from $14.3 billion in 2014 to $18.1 billion in 2018. That’s predominantly thanks to paid streaming, according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, or IFPI. Today, paid and ad-supported streaming together represent almost half of all global recorded music revenue. (Physical sales of CDs and records still account for 25%; the rest comes from other avenues, like performance rights.) And Spotify—with 232 million monthly users and 108 million paying subscribers globally—leads the pack with more than a third of the streaming market, estimates U.K. market researcher Midia. Even Swift has gained an appreciation for the benefits of Spotify. Today, the entirety of the “Shake It Off” singer’s catalog is available to stream on the app, including 1989 and her latest album, Lover. Spotify and Ek have reaped the benefits of his platform’s rise. Ek took the company—which he cofounded with Martin Lorentzon in 2006 in Stockholm—public via a direct listing (rather than a traditional IPO) in April 2018. Today, Spotify has a market value of about $21 billion, and Ek himself has an estimated net worth of nearly $2 billion. Analysts estimate that the company will reach $7 billion in sales for 2019. Spotify’s overall prospects are so robust, according to BCG, that it ranks No. 5 on this year’s Fortune Future 50 list of the companies best positioned to generate long-term growth. But there’s no guarantee that Spotify will hold its position at the top of the charts. Encouraged by streaming audio’s growth, tech giants Apple and Amazon have entered the fray. Each has extraordinarily deep pockets—not to mention a home court advantage as the makers of the iPhones and Echo devices on which so many listeners access their music. Meanwhile, the maturation of major streaming music markets such as the U.S. and the U.K. has Spotify and its rivals chasing emerging opportunities in Brazil, Mexico, India, and “late adopter” nations like Germany and Japan. Already, Spotify has found profits hard to come by. After reporting its first-ever quarterly profits in the third and fourth quarters of 2018, the company returned to losses in the first half of this year, leading some investors to sour on the stock. Since Spotify’s listing, its shares are down 30% versus a 15% gain for the Nasdaq. And the painstakingly negotiated agreements that Spotify has with the major labels—the majority of the music streamed on the service is licensed from Universal, Sony, and Warner plus indie agency Merlin—don’t leave the company much room to boost its profit margins. Spotify has been a savior for the music business. Now it needs to prove that it’s not a one-hit wonder. |

****

|

Spotify对唱片行业的影响到底有多大?不妨先看看这个行业在世纪之交的情况。1999年,全球唱片行业的营收达到了创纪录的252亿美元,均来自于实体媒介的销售,例如黑胶唱片、磁带,以及最为重要的CD。(作为对比,星巴克去年的销售额不到250亿美元。) 随后,Napster横空出世。同一年推出的臭名昭著的文件分享平台让本土盗版现象泛滥成灾,不过这个现象在音乐行业倒是从未消失过。翻过这一页之后:国际唱片业联合会的数据显示,在苹果于2003年推出其 iTunes Music Store之际,音乐行业的年营收额下降了40亿美元。 在2006年Spotify面世之际,唱片业销售额又下滑了10亿美元。然而,唱片公司依然对流媒体服务充满了顾虑,艾克则将这一服务描绘为打击盗版的解决方案。该行业于2008年在美国本土之外与Spotify达成了音乐授权协议,但直到2011年Spotify才通过谈判拿到了美国市场的授权。受其业务被突然侵蚀的警报,所有大型唱片公司终于与Spotify签署了授权协议,并低调地联合购买了该公司14%的股份。(环球、华纳和索尼拒绝对本文置评。) |

Just how hard has Spotify rocked the record industry? Consider where the business was at the turn of the millennium. In 1999, still riding a multi-decade wave of growth, the global recorded music industry logged a record $25.2 billion in revenues, all of it via sales of physical media like vinyl records, cassette tapes, and above all, compact discs. (For perspective, Starbucks had just under $25 billion in sales last year.) Then Napster came along. The launch of the notorious file-sharing platform that very same year took the homegrown piracy that has always been part of the music industry and put it on steroids. Cue the slide: By the time Apple launched its iTunes Music Store in 2003, annual music industry revenues had dropped by some $4 billion, according to the IFPI. By the time Spotify launched in 2006, music sales had fallen another $1 billion. But the record companies were still wary of the streaming service, which Ek was pitching as a solution to piracy. The industry cut a deal with Spotify for music rights outside the U.S. in 2008, but it took until 2011 for Spotify to negotiate its way into the U.S. market. Alarmed by the sudden erosion of their business, all of the major record labels finally signed licensing deals with Spotify and quietly took an estimated 14% combined stake in the company. (Universal, Warner, and Sony declined to comment for this story.) |

|

唱片品牌Astralwerks前负责人、纽约大学克莱夫·戴维斯唱片学院教授埃罗尔·克洛斯尼说:“主流唱片公司对于流媒体的出现持观望态度。唱片行业曾几何时对这一行业并不是很看好,因为它们对流媒体的生命力存在质疑。然而,这个行业如今已经站稳了脚跟。” 唱片行业掌握的部分事实依据在于,它们意识到Spotify可以提供卓越的用户体验,而且是客户如今所渴求的体验,尤其是在这个智能手机和高速Wi-Fi无处不在的时代。纽约音乐工作室音乐人、制作人和音乐老师杰夫·培瑞茨说:“它为听众提供的服务简直棒极了,而且可以获取各种各样的音乐。”培瑞茨此前共事过的艺人包括马克·隆森和拉娜·德雷。 但给予听众如此多的自主权意味着必须彻底重新构建艺人和唱片公司的盈利模式。培瑞茨表示:“普通听众并不关心资金在行业如何流动以及最终的去向。” Spotify通过两种方式盈利。第一种是在免费收听服务中插播广告,听众可以获取有限的曲库点播权限。这一方式在今年上半年创造了2.91亿美元的收入,占其总收入的比例不到10%。剩余大部分的营收,也就是今年上半年91%的营收——28.9亿美元,则来自于付费订阅服务收入,该服务可以为听众提供点播任何音频的权限。公司一直认为,其免费服务是通往付费服务的输送通道,而且这一理论有数据作为支撑:Spotify超过60%的新付费用户都是由免费用户升级而来。公司大部分的业绩增长都源于公司在这两个领域的努力,也就是更有效地利用免费客户群来捞金,同时吸引更多用户加入付费行列。这两个领域的年增速均超过了30%,而且公司还对固定成本进行严格的管控,为的是不让其超过营收增速。 然而,行业观察家本·汤普森去年在他的新闻稿《Stratechery》中指出,Spotify的优势受到了其边际成本的限制,也就是公司向唱片公司支付的版权费(公司借此获得其海量音乐内容的授权)。汤普森写道,尽管其用户和营收都出现了大幅增长,但Spotify的利润率却“掌握在唱片公司的手中”,而且按绝对价值计算,其亏损正在扩大。 华尔街对此也是越来越担心,不止一名分析师认为公司需要降低其版权费来支撑其市值。德意志银行的分析师劳埃德·沃尔姆斯里说:“我们都觉得Spotify某一天可能会在其业务中推出高更利润率的产品,但我们一直都没有看到有任何现实迹象表明公司做到了这一点。”Spotify和各大唱片公司正在探讨其今后两年的交易,而且这些对话必然是火药味十足。尽管Spotify的规模比以往任何时候都要大,但来自于亚马逊、苹果和其他对手的日趋激烈竞争也给唱片公司提供了新的议价筹码。 正如一名与Spotify依然有关联的音乐行业高管说的那样:“只要出现一次失败,Spotify就会与市场脱节。” |

“The major labels kind of sat on their hands at the advent of streaming,” says Errol Kolosine, former head of the record label Astralwerks and a professor at New York University’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music. “The music industry went through a period of relative uncertainty, driven by not understanding the permanence of streaming. That reality has set in now.” Part of the industry’s reality check was to realize that Spotify, especially in the era of smartphones and speedy Wi-Fi, offered a superior experience—one that customers would now demand. “What it provides for the listener is amazing,” says Jeff Peretz, a studio musician, producer, and music teacher in New York who has worked with acts such as Mark Ronson and Lana Del Rey. “They have access to everything.” But giving listeners so much control meant that the way artists and labels made money had to be completely rethought. Adds Peretz: “The average listener doesn’t care about how money moves through the industry and where it winds up.” Spotify makes its money in just two ways. It generates less than a tenth of its revenue, or $291 million in the first half of this year, by selling advertising against its free listening service, which offers limited, on-demand access to its audio catalog. It generates the vast remainder—91% in the first half of the year, or $2.89 billion—from fees for its paid subscription service, which offers unlimited access to the catalog, online and off. The company has long held that its free service serves as a funnel to its paid counterpart, and it has the data to back up the claim: More than 60% of new paid subscribers to Spotify upgraded from its free tier. Most of the company’s growth has been the result of working within these two categories: more effectively monetizing its free customers, and attracting more paid subscribers. Annual growth in both categories tops 30%, and the company keeps a tight enough lid on fixed costs so as not to outpace revenue growth. But, as industry observer Ben Thompson pointed out last year in his Stratechery newsletter, Spotify’s upside is limited by its marginal costs—that is, the royalties it pays the record labels from which it licenses the vast majority of its music catalog. Despite its impressive continued growth in terms of users and revenue, Spotify’s margins are “at the mercy of the record labels,” Thompson wrote, and its losses are growing in absolute terms. Wall Street has grown concerned as well, with more than one analyst arguing that the company needs to lower royalty rates to justify its market value. “We can all contemplate ways that Spotify could one day add in higher margin products to their business,” says Deutsche Bank analyst Lloyd Walmsley. “We just haven’t seen any real signs of that coming to fruition.” Spotify and the labels are in the middle of negotiating their next two-year deal, and the talks promise to be intense. While Spotify is bigger than ever, the increasingly fierce competition it faces from Amazon, Apple, and others gives the labels new leverage As one music industry executive with continued ties to the company puts it: “Spotify is one fail away from becoming less relevant.” |

****

|

西西里亚·科维斯特从未来打来的这个电话似乎很是应景。担任Spotify全球市场负责人的科维斯特在日本通过视频与我进行了对话。日本是全球第二大音乐市场,但在流媒体领域却是一个后来者。当时她在东京,早上6:30,朝阳的光芒洒在她像素化的肩上。科维斯特解释了为什么日本对于Spotify来说是一个巨大的机遇。 她说:“日本一直是一个非常依赖于实体的市场。我们有能力和机会向这里的人们展示他们以前从未见过的事物。” 这个日出国度并非是Spotify认为自己可以俘获新用户芳心的唯一市场。音乐界认为,在全球十大顶级音乐市场之中,至少有三分之一在流媒体服务采用方面并不成熟,要么是因为人们依然对CD青睐有加(日本),要么是缺乏技术基础设施(巴西)。 这对于Spotify来说是个好消息,因为公司目前正面临着巨大压力,而且迫不及待地希望向外界展示:公司如今已经成为了这一领域的主导者,因此可以可靠地将听众转化为利润。科维斯特受命开展的工作包括国际扩张和产品本土化,他认为增长之路取决于如何平衡地开展“三位一体”策略。 她说:“要实现增长,摆在我们面前的有这样几条道路:在现有市场内实现增长;开拓新领域;提升我们的产品服务。这并不只是一件事情,你必须有足够多的鸡蛋,并把它们放在足够多的篮子中。” 到目前为止,Spotify将鸡蛋放在了79个篮子中,比亚马逊音乐的30多个国家要多得多,但比苹果的110多个国家则逊色不少。为了拓展其覆盖范围,Spotify在7月宣布了其所为的Spotify Lite,这是其标志性流媒体服务的“袖珍快速精简版”,它针对老旧型号电脑硬件和较慢的手机网络进行了优化,并覆盖了36个新兴市场,包括阿根廷、巴西、加拿大、印度和墨西哥。 科维斯特说:“全球共有近50亿部智能手机。由此可见,现有的潜力是巨大的。” 是不是明显漏掉了谁?中国。Spotify还未正式登陆这个全球人口数量最多的国家,不过它在2017年年底与腾讯音乐交换了少数股权,也让其获得了间接的立足之处。市场研究公司Midia估计,腾讯音乐于12月在纽交所上市,其市值达到了220亿美元,该公司占据着全球8%的流媒体音乐市场,落后于Spotify、苹果和亚马逊。在全球音乐流媒体市场,Spotify和腾讯共计拥有接近多数的市场份额,也为其应对科技巨头对手的竞争提供了坚实的壁垒。(苹果和亚马逊均未回复《财富》杂志有关本文的置评请求。) 这并不是在说科维斯特对这个问题感到寝食难安。这位Spotify高管以蔑视的口吻说:“相信人们会感到惊讶的是,我们基本没有花时间去研究如何竞争,而是专注于独立完成我们能够做的事情。我们是一家全球性的服务公司,到目前为止是这一领域的老大。我们仅关注音频,这里的区别还是很大的。” |

It seems appropriate that Cecilia Qvist is calling from the future. Qvist, who serves as Spotify’s global head of markets, is speaking to me via videochat from Japan, the world’s second-largest music market but a late bloomer when it comes to streaming adoption. It’s 6:30 a.m. in Tokyo; fledgling rays of sunlight peek over her pixelated shoulders. Qvist explains why Japan represents such a big opportunity for Spotify. “Japan has been a very physical market,” she says. “We have the ability and opportunity to show them things they haven’t seen before.” The land of the rising sun isn’t the only place where Spotify believes it can dazzle new users. The music industry considers at least a third of the top 10 global music markets to be immature when it comes to streaming adoption, either because of a lingering love of CDs (Japan) or lagging technical infrastructure (Brazil). That’s good news for Spotify, which is under great pressure to show that, category dominance now achieved, it can reliably turn listeners into profits. Qvist, whose mandate includes international expansion and product localization, believes the path to growth lies in balancing a trio of strategies. “There are a few ways for us to grow,” she says. “Growth within existing markets. Expanding into new territories. Enhancing our product offering. It’s not just one thing. You have to have enough bets in enough buckets.” To date, Spotify has bets in 79 buckets—far more than Amazon Music, which is available in about three dozen countries, but well behind Apple Music, which operates in more than 110. To broaden its reach, Spotify announced in July what it dubs Spotify Lite, “a small, fast, and simplified version” of its signature streaming service that’s optimized for older computer hardware and slower cellular networks. It launched Lite in three dozen emerging markets, including Argentina, Brazil, Canada, India, and Mexico. “There are almost 5 billion smartphones around the globe,” Qvist says. “Just look at the potential that exists.” One notable omission? China. Spotify doesn’t officially operate in the most populous country in the world, though in late 2017 it swapped minority stakes with Tencent Music, giving it an indirect foothold. Midia, the market research firm, estimates that Tencent Music—which went public on the New York Stock Exchange in December and carries a market capitalization of $22 billion—claims about 8% of the global streaming music market, behind Spotify, Apple, and Amazon. Together, Spotify and Tencent control a near-majority of the world’s music streaming business, providing a bulwark against competition from its Big Tech rivals. (Neither Apple nor Amazon responded to Fortune’s inquiries for this story.) Not that Qvist is terribly concerned about it. “You would be surprised how little time we spend looking at competition versus what we can do on our own,” the Spotify executive says with an air of defiance. “We are a global service, by far the biggest. We are solely focused on audio, and that’s a big difference.” |

****

|

这为我们带来了播客。如果Spotify通过其他形式的音频内容来进行扩张,我们可能并不会感到惊讶。这完全是另外一回事,而且Spotify心甘情愿地为两家播客内容制作商支付了溢价。 2月,Spotify宣布,公司以2.3亿美元收购了纽约Gimlet Media,后者因其播客系列《回复所有人》(Reply All)和《犯罪之城》(Crimetown)知名。一个月后,Spotify又斥资5600万美元收购了Parcast,该公司因其真实犯罪作品而闻名,包括《悬而未决的谋杀案》(Unsolved Murders)。这些举措背后的事实在于,Spotify已经成为了坐上了播客行业的第二把交椅(仅次于位于加州库比蒂诺的已知的竞争对手)。这些举措还凸显了Spotify通过打破音乐合约限制来改善业绩增长的必要性。 第二位要求匿名的音乐行业高管在评论其雇主与Spotify的商业关系时表示:“向播客转变——我们对这一领域的现状十分了解。” 尽管播客越来越受欢迎,但播客的业务规模与音乐相比依然要小得多。此外,这位音乐高管还表示,播客的盈利模式与音乐不同。版权费规模不同,受众本身也不一样。这位高管说:“精于播客之道并不能解决与[Spotify]音乐业务地位相关的所有问题。这是一个十分有趣的机会,我能理解Spotify为什么会选择这条道路。但它并不能力挽狂澜,还是个未知数。” Spotify的首席内容官多恩·奥斯特洛夫对此持有不同意见。这位在电视行业摸爬滚打了多年的高管(曾经担任CW和UPN电视网总裁多年)从位于世贸中心4号楼的Spotify新美国总部给我打来电话,解释了播客对于公司的重要性。Spotify充满乐趣的纽约总部共有十几层楼,面积达56.4万平方英尺,它更像是一个垂直园区,而不是办公室。这里的各种待遇,包括免费餐饮以及如海般的站立式办公桌,彰显了公司的增长速度。 奥斯特洛夫表示,播客业务的格局类似于Spotify在00年代音乐行业的际遇。对于Spotify来说,播客这个十分诱人的机遇也是吸引新一代消费者Z一代的另一把利器,他们收听播客的热情在不断攀升。奥斯特洛夫说,2017年,27%的Z一代至少每个月收听播客一次,今年这个数字已经达到了40%。 她说:“播客已经面世多年,但它们在某些方面依然处于发展初期,这块业务异常碎片化。我们看到,播客听众正在呈爆炸式增长,因此它为Spotify打造和统一这个行业提供了一个机会。” 这也为Spotify将其内容收入麾下节目单提供了机会,这样就不用再去购买版权。播客并非是公司在这一方面的唯一尝试。去年,Spotify试推行了一项服务,允许独立艺人将其作品直接上载至平台,类似于流媒体同行SoundCloud的做法,以越过中间人,也就是唱片公司。可以预见的是,音乐行业对这一举措颇有微词。7月,Spotify关闭了这个项目,称公司希望专注于为艺人和唱片公司提供服务。第二名行业高管说:“我依然认为[直接上载]可能是其长远规划的一部分,但难以改变现状。” 所有这一切都十分重要,因为Spotify没有抵御苹果和亚马逊的杀手锏:硬件。苹果自身的数据显示,公司在全球拥有超过14亿iPhones、iPads、TVs和 Macs活跃用户,而这些用户亦是Apple Music可以开发的对象。亚马逊已经售出1亿台配备Alexa个人助理的设备,而且拥有1亿多Prime会员,这两类人群均可以访问其音乐内容。作为对比,Spotify必须通过别人家的设备尽可能多地吸引用户的眼球,然而其财大气粗的竞争对手在一夜间便能组建一支用户大军。Spotify的继续增长证明了其强大的用户数量,但其未来前景面临的威胁依然存在。 |

Which brings us to podcasts. It was perhaps unsurprising that Spotify might look to other kinds of audio as a way to expand; it was another matter entirely that it was willing to pay a premium for a pair of podcast producers. In February, Spotify announced that it had acquired New York–based Gimlet Media, known for its podcast series Reply All and Crimetown, for $230 million; the following month the company shelled out $56 million for Parcast, known for true-crime shows like Unsolved Murders. The moves capitalized on the fact that Spotify has become the second-largest player in podcasting (behind a certain competitor in Cupertino, Calif.). They also underscored Spotify’s need to break free from the constraints of its music contracts to see improved growth. “The shift to podcasting—we understand what’s going on there,” says a second music industry executive, who requested anonymity, citing his employer’s business relationship with Spotify. Despite its booming popularity, however, podcasting is still a much smaller business than music. In addition, the music executive adds, podcast economics aren’t the same as those for music. The royalty pool is different, and the audience itself is different. “Being really great at podcasting does not solve all the issues with respect to [Spotify’s] position in the music business,” the executive says. “It’s an interesting opportunity; I understand why they’re going after it. But it’s not a game-changer. The jury’s out.” Dawn Ostroff, Spotify’s chief content officer, begs to differ. The longtime television industry executive (she was for years president of the CW and UPN networks) calls me from Spotify’s new U.S. headquarters at 4 World Trade Center to explain why podcasts hold promise for the company. At 564,000 square feet across more than a dozen floors, Spotify’s playful NYC digs are more of a vertical campus than an office, and the perks within—including free meals and an ocean of standing desks—signal the company’s rapid ascent. Ostroff says the landscape for podcasts mirrors the one that Spotify encountered in music in the 2000s. They’re also an attractive opportunity for Spotify to gain additional leverage over the next generation of consumers: Generation Z, which is listening with increasing enthusiasm. In 2017, 27% of the cohort listened to a podcast at least once per month, Ostroff says; this year, 40% tuned in. “Podcasts have been around for years, but they’re still nascent in other ways—the business has been incredibly fragmented,” she says. “It’s an opportunity for Spotify to build and unify the industry at a time when we’re seeing listenership explode.” It’s also a chance for Spotify to own the content in its catalog, rather than license it. Podcasts haven’t been the company’s only attempt at this. Last year, Spotify experimented with a service that would allow independent artists to upload their work directly to its platform, à la streaming peer SoundCloud, and cut out the middlemen—that is, record labels. Predictably, the initiative was met with some complaints from the music industry. In July, Spotify shuttered the program, saying it wanted to focus on serving artists and labels. “I still think [direct uploads] might be part of their long-term perspective,” says the second industry executive. “But it wasn’t moving the needle.” All of this is important because Spotify lacks a key tool to fend off Apple and Amazon: hardware. According to its own count, Apple has more than 1.4 billion active iPhones, iPads, TVs, and Macs around the globe to leverage for Apple Music; Amazon has sold more than 100 million devices with its Alexa personal assistant and counts more than 100 million members of Prime, both of which allow for access to its music catalog. Whereas Spotify must fight for every eyeball on someone else’s device, its well-heeled rivals can activate a customer base overnight. That Spotify continues to grow is a testament to its strong engagement figures, but the threat to its future prospects remains. |

****

|

丹尼尔·艾克不安地环顾着四周。哥伦比亚广播公司《This Morning》节目的主持人盖勒·金刚刚在直播现场向他问道,在经历了三年冰冻期之后,他如何成功地修复了Spotify与泰勒·斯威夫特已然破裂的关系。金笑着说:“泰勒有首歌《Love Story》,里面唱道‘宝贝,答应我吧。’你是不是就是这样说的?” 这位首席执行官笑着说:“比这个稍微复杂点。”他还说自己去了很多次纳什维尔,才说服这位流行明星流媒体重新考虑这个已经颇具规模的流媒体行业。 事实上,艾克一直都是优势在握。对于已经与大型唱片公司签约的艺人来说,包括已经与环球签订了全球合约的斯威夫特,进驻所有拥有其听众的平台符合其个人利益。Spotify自与斯威夫特分手之后一直都在致力于培养听众群体。在这期间,实物唱片专辑的销量一落千丈。经济压力会迫使斯威夫特重回Spotify的怀抱,这只是迟早的问题。 这并非是说Spotify已经解决了长期以来一直困扰它的问题:艺人薪酬。根据公司自己的计算,其总营收的三分之二还多流向了艺人、唱片公司、出版商和发行商的腰包中。然而,流媒体收入中各单项收益实在是低的令人沮丧。 Spotify一直对具体的数字和付费比率避而不谈,而这些都取决于与唱片公司的协议。但有报告指出,单次播放量的付费比率在十分之三到十分之八之间,也就是100万次播放量可能高达8000美元。其中大部分进入了歌曲总版权方的腰包。词曲作家自己拿到的要少一些。(美国版税委员会去年做出的一项决定意欲将词曲作家的收入提升近一半;目前该动议徘徊于申诉中。) 这些费率并非只针对Spotify。行业消息人士称,苹果和亚马逊的付费比率与Spotify相当。由多名知名艺人和Sprint共同持有的Tidal当前的日子并不好过,但其付费比率更高。SiriusXM旗下先驱电台服务Pandora的付费比率则要少得多。 然而如果将它们看作一个整体,流媒体服务事实上是听众发现艺人的强大引擎,也是唱片公司正在直茁壮成长的摇钱树。正如一名音乐公司高管说的那样:“我们是亦敌亦友的关系。我们都需要对方。从我们的利益角度来说,他们对我们的依赖度越高越好。同时,我们的艺人则需要尽可能多地接触更多的听众。” 为了保住其行业领先地位,Spotify必须继续平衡好与唱片行业之间这种既合作又竞争的关系。当然为了安全起见,Spotify最好还是避免再次交恶泰勒·斯威夫特。(财富中文网) 本文登载于《财富》杂志2019年11月刊。 译者:冯丰 审校:夏林 |

Daniel Ek glances around nervously. Gayle King, the CBS This Morning anchor, has just asked him live on the air how, after three icy years, he managed to mend Spotify’s broken relationship with Taylor Swift. “She’s got a song, ‘Love Story,’ that says, ‘Baby, just say yes,’ ” King offers with a smile. “Is that what you did?” “It was slightly more complicated than that,” the CEO says with a chuckle, adding that it took several trips to Nashville to convince the pop star that streaming had come around enough for her to reconsider. In truth, Ek always had the upper hand. It’s in the interest of artists signed to major labels—including Swift, who has a worldwide deal with Universal Music Group—to be on every platform where they have listeners. Spotify has done nothing but build that base since its spat with Swift; in the interim, physical album sales have fallen off a cliff. It was only a matter of time before economic pressures would push Swift into Spotify’s open arms. That’s not to say that Spotify has solved the one bugaboo that continues to dog it: artist payouts. By the company’s own calculations, more than two-thirds of its total revenues are funneled back to artists, record labels, publishers, and distributors. And yet, the itemized numbers for streaming revenue feel distressingly low. Spotify is cagey about revealing specific figures and payout rates, which depend on label agreements. But reports have pegged rates between three-tenths and eight-tenths of a cent per stream—or up to $8,000 for a million streams. Most of that goes to the master holder of the song rights. The songwriters themselves get less. (A ruling last year by the U.S. Copyright Royalty Board aimed to hike songwriters’ share by almost half; it’s stuck in appeals.) Those figures aren’t unique to Spotify. Apple and Amazon pay similar rates, industry sources say. Tidal, the troubled streaming service co-owned by a roster of famous artists and Sprint, pays a little more; Pandora, the pioneering radio service owned by SiriusXM, pays a lot less. Taken as a group, though, the streaming services have proved to be a powerful engine for listeners to discover artists and a growing revenue generator for labels. As one music executive puts it: “We’re frenemies. We need each other. It’s in our interest for them to be as dependent on us as possible. And our artists need to reach as many customers as possible.” To stay on top, Spotify must keep that balance between partner and adversary with the record industry. And just to be safe, it should probably avoid starting any new fights with Taylor Swift. This article appears in the November 2019 issue of Fortune. |