美国中产阶级面面观:收入越来越低,人数越来越少

|

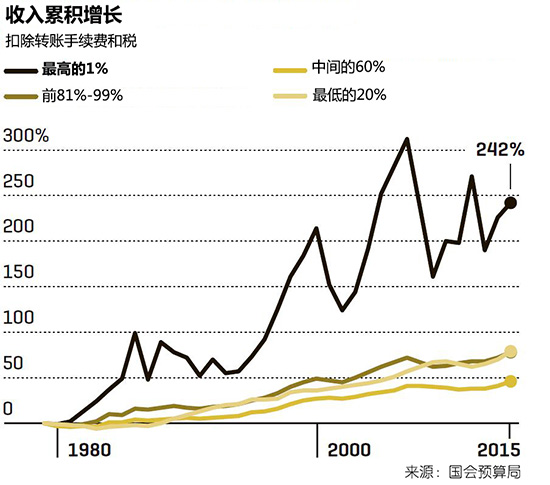

绝大多数的美国人自视为“中产阶层”。但这意味着什么却众说纷纭。理查德·里夫斯和布鲁金斯学会的同事们已经用过十几个经济公式来定义这个弹性很大的群体,其基本标准是人们的年收入:居民收入介于X和Y之间;个人收入和全国平均值之差在百分之几以内;和贫困线的距离,等等。综合而言,中产阶层的范围非常大——有年收入为1.3万美元的兼职酒吧侍者,也有住在郊区、一年赚23万美元的“强力”夫妇,它覆盖了90%的美国居民。 其他经济学家和社会科学家从不同的层面来为这个群体划定界限,比如富裕程度或消费能力、专业或受教育水平、居住在怎样的社区,甚至是非常美国式的想法——自我定位,也就是说,如果你觉得自己是中产阶层,你就是。 作为布鲁金斯学会的高级研究员兼中产阶层未来项目负责人,里夫斯说:“有时候我觉得有多少被称为中产阶层的美国人,就有多少中产阶层的定义。”他迅速拿出了自己最喜欢的非经济定义:“有两台冰箱的人是中产阶层。新冰箱放在厨房里,旧的在车库或地下室,用来放啤酒。” 他还说,美国是一个中产阶层国家,就建立在中产阶层的理想上。因此,自行定义为中产阶层从某些角度来说很励志,这可能和常见的观点相悖。“美国人不喜欢被视为上层人士、势利小人、傲慢者、贵族、上流阶层等等。”作为经济学家,里夫斯自称为“复苏的英国人”。他有本新书叫做《Dream Hoarders》,对象正是这个越发稀少的美国上层群体。“人们也不喜欢自认为穷人,甚至不喜欢打工族这个称号。要说美国有阶层意识,那它往往就是以中产阶层为核心。” 所有这些都成了进行衡量的障碍。如果说估算中产阶层的规模已经够难了,要断言这个群体内的环境已经发生变化更是难上加难。而这正是我们的专题报告要探讨和展示的内容。近年来,数百万中产阶层的生活变得更加艰难了。简单来说就是,对太多的人来说,美国梦已经离他们远去。 这样的判断似乎和最近的经济数据向悖,甚至和之前的长期上行趋势背道而驰。经常被引用的美联储的消费者财务状况调查报告指出,2013年至2016年,美国家庭的平均收入上升了10%。同时,失业率处于1969年,也就是人类登月那一年以来的最低点,原因是2010年以来的民营行业创造了大约2000万个就业机会。工资终于也在长期停滞后开始上涨。所有这些都是千真万确的好消息,不是吗? 但差不多所有表现良好的近期经济指标都有一个前提,或者说注释,那就是一个巨大而且可能仍在增长的群体被放到了统计范围之外。大家可以考虑一下最基本的因素——工资。皮尤研究中心的数据显示,2018年11月,非管理人员的小时工资已接近23美元,而考虑到通胀因素后,如今上班族的购买力略低于1973年1月的水平(按2018年价格水平计算为23.68美元)。 |

The vast majority of Americans consider themselves “middle class.” No one can quite agree, though, on what that means. Richard Reeves, along with colleagues at the Brookings Institution, has cataloged no fewer than a dozen economic formulas that seek to define this elastic cohort largely by what people earn each year: household income between X and Y; personal income that’s within some percentage of the national median; distance from the poverty line; and so on. Combine the lot, and the range of who might be considered middle class is extraordinarily expansive—including anyone from a single, part-time bartender scratching by on $13,000 a year to a suburban power couple pulling in $230,000, or 90% of American households in all. Other economists and social scientists stretch the boundaries of membership in different dimensions, based on degrees of wealth or spending power, professional status or education level, what neighborhood you live in, or even on that very American of conceits, self-determination—which is to say, if you think you’re middle class, you are. “I sometimes think there are as many definitions of the middle class as there are Americans claiming to be middle class,” says Reeves, a senior fellow at Brookings and director of its Future of the Middle Class Initiative, who quickly throws in one of his favorite noneconomic definitions: “You’re middle class if you have two refrigerators. You have a new one in your kitchen, and you have your old one in the garage or basement, where you keep your beer.” The U.S. is a middle-class nation—it was founded on middle-class ideals, he continues. And so defining one’s self as middle class is, perhaps counterintuitively, aspirational in some ways. “Americans don’t like the idea of seeing themselves as upper crust, snobs, snooty, aristocrats, upper class, et cetera,” says Reeves, an economist and self-described “recovered Brit” who has written a new book, Dream Hoarders, precisely on that rarefied American upper crust. “People also don’t like to think of themselves as poor, or even as working class. To the extent that the U.S. has a class consciousness, it tends to be around the middle class.” All of which creates a challenge of measurement. If sizing up the middle class is difficult enough, it’s that much harder to say that circumstances within this group have changed. And yet that is precisely what we’ve devoted the 28 pages in this special report to saying—and showing. Life has gotten harder in recent years for millions of people within the middle class. Put simply: For too many, the American dream has been fading. Such an assertion may seem to fly in the face of recent economic data and even the long upward slope of history. Between 2013 and 2016, after all, the median income for U.S. families grew 10%, according to the Federal Reserve Board’s oft-cited Survey of Consumer Finances. The unemployment rate, meanwhile, is at its lowest level since 1969—the year of the moon landing—as the private sector has generated some 20 million new jobs since 2010. Wages, too, are at last starting to climb after a long stretch of stagnation. All really good signs, no? And yet for nearly every rah-rah measure in the economy of late, there is an asterisk: a footnote that suggests that a huge and perhaps growing subset of Americans is being left off the dance floor. Consider the most basic: wages. For non-supervisors, average hourly earnings hit nearly $23 in November—a fact that, according to data from the Pew Research Center, gives today’s workers slightly less purchasing power than those in January 1973, once inflation is factored in ($23.68 in 2018 dollars). |

|

这些年来,就业信息及咨询公司CareerBuilder一直在通过哈里斯民意调查机构对美国工商界就业者进行大规模调查。2017年,在近3500名受访者中,表示自己总是或经常过的“紧巴巴”的人多达40%,和2013年相比上升了4个百分点。 这样的数据在一定程度上解释了纽约联储最近的一项研究结果,那就是美国家庭的负债余额达13.5万亿美元。2018年9月,家庭债务余额连续第17个季度上升,目前水平已经超出2008年的前期高点8000多亿美元。以美联储为数据来源的贷款信息网站LendingTree称,从50年前开始统计的美国人非房贷债务占可支配收入的百分比处于历史最高点。该网站表示,总而言之,我们的消费债务占收入的26%以上。 利率较低时,尽管此项负担不会让人痛心疾首,但仍让许多人感到如坐针毡。不过和直线上升的联邦债务不同,这项连绵不绝的债务完全属于个人性质,而且人们每个月都会得到账单邮件的提醒。2018年12月,个人财务网站NerdWallet报道称,负债居民的平均信用卡循环余额,或者说从一个账期到另一个账期不断出现的“应还款金额”为6929美元。 就连那些没有信用卡债务或者高额学生贷款的人也发现自己每个月都有反复出现的开支。医疗保险和看病的费用增长的速度要比工资快得多。凯泽家庭基金会指出,过去10年中,由于保险免赔额上调,上班族自行承担开支的上涨幅度是工资的8倍。美联储则表示,2017年逾四分之一的成年患者没有接受所需的治疗,原因是他们负担不起费用。 没错,整个美国的住房成本全面回落,但要点在于,房价下跌的地方缺乏就业机会。想在硅谷的初创企业或者波士顿的生物科技公司工作吗?哈佛大学的住房研究联合中心指出,在圣何塞,60%的年薪不超过7.5万美元的租房者要把超过30%的收入交给房东。 |

For years, the company CareerBuilder has conducted, via the Harris poll, a large survey of U.S. workers across the business landscape. In 2017, a striking 40% of the nearly 3,500 respondents said they either always or usually live “paycheck to paycheck”—a level that was up four percentage points from the company’s 2013 poll. Such data is explained in part by recent research by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which reveals the $13.5 trillion IOU that American families have kept locked inside their desk drawers. This past September, aggregate household debt balances jumped for the 17th straight quarter, with the debt now more than $800 billion higher than it was at its previous peak in 2008. The loan comparison site LendingTree, drawing on data from the Federal Reserve, reports that as a percentage of disposable income, Americans’ non-housing-related debt is higher than it has been since measurement began a half-century ago. Collectively speaking, our outstanding consumer debt, says the site, is equivalent to more than 26% of our income. With interest rates low, that burden is still a pinch for many, rather than a gouging bite—but unlike with our skyrocketing federal debt, this cascading obligation is still achingly personal, with reminders coming in the mail month after month. In December, the personal finance site NerdWallet reported that average revolving credit card balances for households with debt—the “You Owe This Amount” figure that carries over from one billing statement to the next—totaled $6,929. Even those without a credit card overhang, or massive student loan debt, find themselves facing a gauntlet of recurring charges each month. The cost of health insurance and medical care have each risen much faster than paychecks have. Over the past decade, out-of-pocket costs to workers from higher insurance deductibles have climbed eight times as much as wages, notes the Kaiser Family Foundation. More than a quarter of adults did without needed medical care in 2017 because they couldn’t afford it, says the Fed. Yes, housing costs nationwide have moderated—but, importantly, not in the places where the jobs are. Want to work for a Silicon Valley startup or a biotech firm in Boston? Six in 10 renters making up to $75,000 a year will pay upwards of 30% of their income in rent in San Jose; four in 10 will do so in Boston, according to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. |

|

对非常多的美国人来说,住房、医疗保健和大学费用是目前超级通胀影响最明显的领域。布鲁金斯学会的里夫斯说:“要定义中产阶层的生活水平,这三个消费领域最合适不过,那就是承担得起一幢不错的房子、有能力送孩子上大学以及无论家里谁病了都有钱去治。”也许正是这样的三重障碍让许多较年轻的美国人觉得他们再也无法达到《Great American Journey》这本书中提到的一个关键里程碑,那就是比父辈生活的更好。美联社-全国民意研究中心公众事务研究部最近的一次调查显示,在15至26岁的美国人中,只有一半人相信自己能做到这一点。 对于这样的历史性倒退,哈佛大学的经济学家拉兹·切提有一些最受称赞的论述。2016年,切提和同事们指出,剔除通胀因素的影响后,收入超过其父母当年水平的80后不到一半。相比之下,做到这一点的40后在90%以上。哈佛大学的一位知名经济史学家和劳动力经济学家克劳迪亚·戈尔丁说:“我们可以看到,跨代际流动出现了崩溃。” 数百万美国人都感到自己被落在了后面——中产阶层和极富有者的差距似乎不断扩大……经济引力法则似乎不再起作用让这样的感觉更令人受挫。 此外,还有一种担心让人更不得安宁,那就是目前速度极快的科技变化正在接二连三地引发行业颠覆——皮尤研究中心认为,人工智能加持的自动化革命将彻底改变一件事,而几乎所有人都认为它是中产阶层的关键标志,那就是一份稳定的工作。 当然,此前的每次工业革命都会引发同样的担忧。里夫斯认为“一个好的起点是对‘这次不同’的说法持怀疑态度。”但他说,对于当前这场革命,有两点值得一问:“一是这次在速度上会不一样吗?二是这次的不同和以前有区别吗?” 让里夫斯略感紧张的是第一个问题——当然,每次自动化横扫之后,商业模式都会改变,会出现新的工作,而且在两个阶段之间会有一个过渡期。里夫斯指出:“经济一定会调整,会有新的就业机会,但得到这些就业机会的人会取代原有的就业者吗?他们上手的速度够快吗?我们说的可不是用20、30、40或者50年从方法A过渡到方法B。我们说的是两年、三年。也就是说人们要以人类历史上前所未有的速度掌握新技能和新工具。” 里夫斯说,最接近这种情况的场景应该是战时动员。那就让它来吧——许多美国人觉得他们已经置身于其中了。(财富中文网) 本文最初刊登在2019年1月出版的《财富》杂志上。 译者:Charlie 审校:夏林 |

Here—in housing, health care, and the cost of college, too—is where the super-inflation hits hardest for a significant share of the nation today. “And it’s quite hard to find three areas of consumption that define the middle class standard of living more than affording a decent home, or being able to send your kids to college or cover health care costs should any of your family fall sick,” says Reeves of Brookings. This tripartite gap, in particular, may well be what has convinced many younger Americans that they won’t ever reach one critical milestone in the Great American Journey—living better than their parents did. (Only half of the 15- to 26-year-olds in a recent poll by the Associated Press–NORC Center for Public Affairs Research thought they would.) Harvard economist Raj Chetty has done some of the most acclaimed work on this historic decline. In 2016, Chetty and colleagues showed that fewer than half of those born in the 1980s earned more than their parents had at the same age, adjusting for inflation. By contrast, of those born in 1940, more than 90% had accomplished the feat. “We can see that there has been a collapse of intergenerational mobility,” says Claudia Goldin, a leading economic historian and labor economist at Harvard. It’s all part of the feeling, for millions of Americans, of falling behind—a feeling made all the more frustrating by the sense that the gap between the middle class and the superrich keeps widening … that the laws of economic gravity no longer seem to apply. And compounding that is one more nagging concern: that the breakneck speed of technological change now disrupting one industry after another—a revolution of A.I.-infused automation—will uproot the one thing that, according to the folks at Pew, virtually everyone agrees is critical to middle-class membership: a secure job. Each previous era’s industrial revolution has, of course, raised the same fears. Reeves thinks “a good starting position is to be skeptical about the claim that this time is different.” But the two things worth asking about the current revolution, he says, are: “One, will it be differently quick this time? And two, will it be differently different?” It’s question No. 1 that makes him a little nervous: Yeah, sure, with every grand sweep of automation, business models change and new positions get created, and there’s a transitional time in between them. “So surely the economy will adjust and new jobs will be created,” he says, “but will those people who are displaced be the ones to get those jobs? And will they get them fast enough? You’re not talking about 20, 30, 40, 50 years of transition between approach A and approach B. You’re talking about two, three years. What it means is people need to reskill, retool at a pace that has never before been witnessed in human history.” The closest thing to it, says Reeves, would be like a mobilization during war. So be it: Many Americans feel like they’re already in one. This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of Fortune. |