通用汽车公司已准备好迎接“后汽车”时代

|

约一百年前,美国到达“马匹顶峰”。1920年,有近2500万匹马穿行于全国的平原、大道、胡同、竞技场、饲养场、港口、农场和脏暗的小巷,负责驮运货物、耕地、打仗,以及拖着马车搭载乘客,脏乱不堪。《美国传统》(American Heritage)杂志称,1900年纽约州罗切斯特市(Rochester, N.Y.)卫生部门的官员估计,全市15000匹马每年产生的粪便足以堆起方圆一英亩、高175英尺的大粪堆。到1930年,美国的马匹数减至1900万。再到1960年,全国只剩下300万匹马。马儿作为昔日主要的交通工具,终于被一项更强劲、更无粪便之忧的新技术彻底取代——“无马之车”,也就是汽车。 一个世纪后,像通用汽车(General Motors,本年度《财富》美国500强排名第10)和福特(Ford,排名第11)一类的汽车制造商面临的难题则是,各自的“无马之车”是否即将赴马儿的后尘。我们或已到达甚至越过了“汽车顶峰”。美国乘用车成交量于2016年创历史新高,为1750万辆,但于2017年跌至1720万辆。十几或二十多岁的人群中,考驾照的人少了:1983年,20至24岁人群中注册比例高达92%,2014年只有77%。 使用汽车不再意味着需要拥有汽车。2017年,Uber全球载客40亿乘次。新一代乘客热衷于拼车——在Lyft提供拼车(Line)功能的城市,40%的乘次由两名以上乘客共享。而且,从五花八门的发布和铺天盖地的报道来看,汽车共享、电动并自动驾驶的科技具有不逊于当年第一批“无马之车”的前景,其发展方兴未艾。 |

About a hundred years ago, the United States reached “peak horse.” In 1920 some 25 million horses roamed the plains, boulevards, cul-de-sacs, rodeos, stockyards, ports, farms, and dingy alleys of America—toting freight, plowing fields, fighting wars, carrying passengers on buggy rides, and making a complete mess. According to American Heritage magazine, in 1900 health officials in Rochester, N.Y., estimated that the city’s 15,000 horses produced enough manure to make a 175-foot-high, one-acre-round pile every year. By 1930 the American horse population had dropped to 19 million. And by 1960 the country had just 3 million horses. The horse had been fully displaced as the dominant mode of transportation by a new technology that was both more powerful and less prone to produce manure—the horseless carriage, a.k.a., the car. A century later, the question facing automakers like General Motors (No. 10 on this year’s Fortune 500) and Ford (No. 11) is whether their horseless carriages are about to go the way of the horse. We may well have reached, or even passed, “peak car.” A record 17.5 million passenger vehicles were sold in the U.S. in 2016, but that number dipped to 17.2 million in 2017, and it could fall under 17 million this year. Fewer teens and twenty¬somethings get their driver’s licenses: While 92% of 20-to-24-year-olds were registered in 1983, just 77% were in 2014. Alternatives to ownership are taking off. In 2017, Uber provided 4 billion rides worldwide. The new generation of passengers has embraced ride-sharing—in cities where Lyft has launched its Line service, 40% of its rides are shared by two or more passengers. And gauged by myriad announcements and breathless media coverage, a world of shared electric, autonomous cars—a technology with all the promise of those first “horseless vehicles”—is just around the corner. |

|

毫不夸张地说,对于通用汽车这样的传统汽车制造商,汽车销量的减少似乎带来了挑战。近一个世纪以来,通用汽车所为无非造车,然后再把车卖给客户。未来短期内,公司仍将如此,但长期局面远不够明朗。汽车生产商、芯片制造商、拼车网络运营商和自动驾驶软件提供方都在不断变化,交织在一起,使得最终形势的预测极为困难。高德纳(Gartner)调研公司的分析人员迈克·拉姆齐长期关注这一领域,他告诉我:“未知因素太多了。”通用汽车公司内部和外人皆知的是:这家110年老牌汽车企业的安稳日子早已不再,未来谁都能坐庄。 再来说说玛丽·巴拉。她于2014年1月担任通用汽车公司CEO,成为美国汽车制造界第一位女掌门人。不同于百视达(Blockbuster)和柯达(Kodak)这类此前受灾企业的领导人,巴拉不否认当前面临的剧变。“我相信改变。”她于5月上旬一次采访中对我说。 我们在帕洛阿尔托市(Palo Alto)四季酒店(Four Seasons hotel)一间名为“协同”(Synergy)的朴素的会议室内面对面坐着。酒店矗立于101国道旁,看似一台巨大的玻璃结构苹果HomePod智能音箱。而巴拉身披一件黑色皮夹克,笑容或有些许戒备,但也很热情。她既显得平易近人,又表现出对通用汽车公司及其员工相当的偏护。 她刚从底特律飞来,要前往曾授予她MBA学位的斯坦福商学院,为劳拉·阿里利亚加-安德森的学生讲一堂课。“自动驾驶较之人为驾驶更安全,该技术正在来临,并且,再加上人工智能和机器学习,前景会越来越好。”她说道。 巴拉与通用汽车公司有很深的渊源。她就出生在底特律附近,毕业于当时的通用汽车学院(General Motors Institute)——一个为公司提供毕业生人才的校企合作项目,并获得电机工程学位。她的父亲雷·马戈拉曾在旁蒂克(Pontiac)一间工厂担任39年的制模工。 |

A world that buys fewer cars seems to pose a challenge, to say the least, to a traditional auto manufacturer like General Motors. For almost a century, GM has engaged in a single process: building cars and selling them to individuals. It will continue to do that in the short term, but the long term is much less clear. Predicting the ultimate shape of this evolving mashup of auto manufacturers, chipmakers, ride-share network operators, and autonomous software providers is immensely difficult. As Mike Ramsey, an analyst at research firm Gartner who follows this space closely, tells me: “There are a lot of unknowns.” One thing that everyone acknowledges, inside and outside of GM: The 110-year-old automaker’s halcyon days are long gone, and the future is up for grabs. Enter Mary Barra, who took over as CEO of GM in January 2014, becoming the first woman to run a U.S. automaker. Unlike the leaders of past victims of disruption like Blockbuster and Kodak, Barra isn’t in denial about the radical change that’s afoot. “I believe in it,” she tells me in an interview in early May. We are seated across from each other in the anodyne “Synergy” conference room of Palo Alto’s Four Seasons hotel, which rises above Route 101 like a great glass Apple HomePod. Barra, sporting a black leather jacket, has a warm if guarded smile. She comes across as both approachable and extremely protective of GM and its people. She has just flown in from Detroit to speak to a class taught by Laura Arrillaga-Andreessen at Stanford’s B-school, where Barra got her MBA. “Autonomous technology that’s safer than a car with a human driver is coming,” she explains, “and it’s going to get better and better and better with technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning.” Barra has GM in her bones. She was born just outside Detroit and graduated with a degree in electrical engineering from what was then called the General Motors Institute, a co-op university program that fed graduates into the company. Her father, Ray Mäkelä, was a diemaker who worked for 39 years in a Pontiac factory. |

|

现在她必须让这家汽车巨头急剧转变发展轨迹。她的挑战是要在维持乃至优化旧模式从而创收的同时,再造通用汽车公司,使之领跑当下疾速演变的出行交通产业。借用该公司高层和管理专家钟爱的一个词——通用汽车必须做到“胆大心细”(ambidextrous)。一方面,巴拉必须协助核心业务取得卓越并不断提升;100%的营业额和利润都来源于此。但对于边缘项目,她也必须在通用汽车公司自动驾驶的电动汽车的研发上予以推动并投入资金。此项工作由Cruise Automation的凯尔·沃格特及其500人团队主导。通用汽车公司于2016年初以10亿美元收购了这家旧金山初创企业。 “胆大心细”管理法由斯坦福商学院的查尔斯·奥莱理在《领导与干扰》(Lead and Disrupt)一书中提出,他与哈佛大学的迈克尔·塔什曼合著此书。“我还没有见过哪个公司因为有了技术而倒闭的。公司要么自己有技术,要么没技术就去买技术。这是决策的问题。”奥莱理就着早餐说道。奥莱理任教于斯坦福为通用汽车公司培养主管的一个项目,他认为巴拉已成功开启了通用汽车公司在未来参与竞争所必需的转型。“在我看来,通用汽车目前的做法相较于其众对手更可能取得成功,尽管没人能够保证。”他说。 |

Now she must prepare the auto giant for a radical lane change. Barra’s challenge is to reinvent General Motors as a leader in the rapidly evolving transportation world, while simultaneously delivering great profits by doing what GM has always done—only better than it ever has. To use a term that is much favored by the company’s leaders and by management gurus, GM must be ambidextrous. On the one hand, Barra must help the core business to excel and continually improve; that’s where 100% of the company’s revenues and profits come from. On the edge, however, she must accelerate and invest in GM’s effort to develop autonomous electric cars, an effort led by Kyle Vogt and the 500 employees of Cruise Automation, the San Francisco startup that GM purchased in early 2016 for around $1 billion. Charles O’Reilly is a Stanford B-school professor who laid out the concepts of ambidextrous management in Lead and Disrupt, a book he wrote with Harvard’s Michael Tushman. “I’ve yet to find a company that failed because of technology,” O’Reilly explains over breakfast. “They either had it or they could buy it. It’s a leadership issue.” O’Reilly, who teaches in a program Stanford runs for GM execs, believes that Barra has successfully driven changes that GM must make to compete in the future. “I think what GM is doing is more likely than their competitors to be successful,” says O’Reilly. “Although there’s no guarantee.” |

|

两年前,我第一次采访玛丽·巴拉。她对我说:“要改变企业文化,首先必须改变人们的行为。关键不在于你说什么,而在于你做什么。” 当时的通用汽车经历了一次点火开关工程纰漏事件,涉及一百多人遇难。还在事后的余波中挣扎。巴拉这话在公司内部引起相当共鸣。此前几十年来,公司因踢皮球的官僚作风而受到诟病。后来调查上述灾难事件的起因,就直接声讨了这“与我何关”的作风。巴拉以这次调查为契机,加紧从公司内部发动转型。而到2016年,效果开始显现。几百项内部改革的着力点——统称为“通用汽车2020”(GM 2020)——开始收获成效。完成了第一次为期两年的“转型领导人”(Transformational Leaders)计划后,70位主管开发出了一系列新项目,例如汽车共享服务Maven。在密歇根州沃伦市的通用汽车技术中心,一整层楼为Maven腾出,有十多个小隔间,几间带门的办公室,一片铺着地毯的宣传和营销用地,以及许多空余场所。 今年春季,我回沃伦参观通用汽车技术中心的大幅整修。从底特律市区的通用汽车总部往北半小时车程,就是技术中心,于20世纪50年代由埃罗·沙里宁设计,是通用汽车公司真正的大心脏。约2000名工程师、设计师和IT专家在此处38幢楼里工作。 迈克尔·阿里纳是一名工业工程师,曾在麻省理工学院(MIT)学习人际网络和创新,现在是通用汽车的人才主任。“两年前你所看到的只是开始,”他说,“现在,这一切已经在公司的血脉里了。” 阿里纳所指的是文化变革,但用来形容我们目前所在的汽车工程中心大楼也很贴切。大堂宽敞,有两层楼高,通风良好,四周墙面是玻璃。大堂内有一家星巴克,各种舒适的沙发长椅,和电影《警察与卡车强盗》(Smokey and the Bandit)中的一辆特兰斯艾姆 (Trans Am)。我们在一张极其低调的前台办公桌前登记,上了二楼。“都是为了大家的工作,”阿里纳说。“为了创建适合大家不同工作方式的空间。” 针对性格内向的员工和喜好安静的员工,办公室里配备了一些 Steelcase公司生产的便携式Brody办公隔间。几排白色桌子用临时墙隔离出来,墙上有冷灰色和明亮的三原色嵌板,这是团队任务的场所。还有一处配有一台大型平板电视的休息区,以及用来鼓励随意交流的宽敞开放空间。餐区的桌面由老旧别克和雪佛兰的引擎盖凿成。这一切都自大楼的玻璃外墙往回收,从而留出一道622英尺的长廊,向外就能眺望极具年代感的园区,而楼层的地面则铺满了自然光。我一时想起苹果在库比蒂诺(Cupertino)新建的总部大楼沿弧形玻璃外墙足足一英里的长廊。 确实,无论在谷歌(Google)、Facebook、赫曼米勒(Herman Miller)、或是其他任何一家我们所熟知的所谓创新企业,沃伦新园区的任何元素都不会显得格格不入。通用汽车高管走访所有上述企业的园区,捕捉灵感,以实现与公司全新工作流程相匹配的全新设计。“重点不在于装修,”巴拉说道,“而在于创造协作环境,并为人们高效工作提供所需资源。我们怎样才能确保员工所处的工作环境起到赋能和赋权的作用,而不是压抑和限制才能?” |

Two years ago, when I first interviewed Mary Barra, she told me, “To change a culture, you have to change behaviors. It’s not what you say, it’s what you do.” Back then, those words had a particular resonance at GM, which was still wrestling with the aftermath of an ignition switch engineering flaw that was linked to the deaths of over 100 people. For decades, the company had been known for its pass-the-buck bureaucracy. That “not my problem” behavior was directly implicated in the study GM commissioned to examine the causes of the debacle. Barra used the study as a cudgel to accelerate her efforts to change GM from within, and in 2016 she was just starting to see the impact. An internal collection of a few hundred change agents, operating under the moniker “GM 2020,” was beginning to make its mark. The 70 executives who had been through the first two yearlong “Transformational Leaders” programs were spinning out new programs like Maven, a car-sharing service. At GM’s technology center in Warren, Mich., one floor had been cleared out for Maven. It had around a dozen cubicles, a few offices with doors, a carpeted area that was used for publicity and marketing, and a lot of empty space. This spring I went back to Warren to see GM’s radical overhaul of the tech center. A half-hour drive north of GM headquarters in downtown Detroit, the tech center, designed by Eero Saarinen in the 1950s, is the real heart of the company. Twenty thousand engineers, designers, and IT specialists work here in 38 buildings. “What you saw two years ago was just the beginning,” says chief of talent Michael Arena, an industrial engineer who studied human networks and innovation at MIT “Now,” he continues, “it’s in the blood of the company.” Arena is describing the culture shift, but he might as well be referring to the building we are in, the Vehicle Engineering Center. The spacious lobby, an airy, two-story-high glass enclosure, features a Starbucks, a variety of comfortable couches, and the Trans Am from Smokey and the Bandit. We checked in at a surprisingly unobtrusive security desk and went to the second floor. “This is all about the work,” says Arena. “It’s all about creating spaces for the different ways people choose to work.” Introverts and others in search of quiet are served by a smattering of Steelcase’s portable Brody cubicles. Group work is often done at rows of white desks set off by temporary walls with panels in cool grays and bright primary colors. There’s a lounge area with a large flat-screen TV, and lots of open space to encourage random interactions. The tabletops in the dining area are hammered hoods of old Buicks and Chevys. Everything is set back from the building’s glass exterior, creating 622-foot-long corridors that look out onto the historic campus, and the floors are flooded with natural light. I’m reminded of the mile-long paths along the curved glass of Apple’s new headquarters in Cupertino. Indeed, nothing about the new Warren campus would look out of place at Google, Facebook, Herman Miller, or any other company we more readily recognize as innovative. Top executives visited the campuses of all those companies for inspiration on a redesign that would suit GM’s new workflows. “This isn’t about furniture,” Barra explains. “It’s about creating an environment for collaboration and giving people tools they need to work effectively. How can we make sure you really have a work environment that’s enabling and empowering, instead of constricting?” |

|

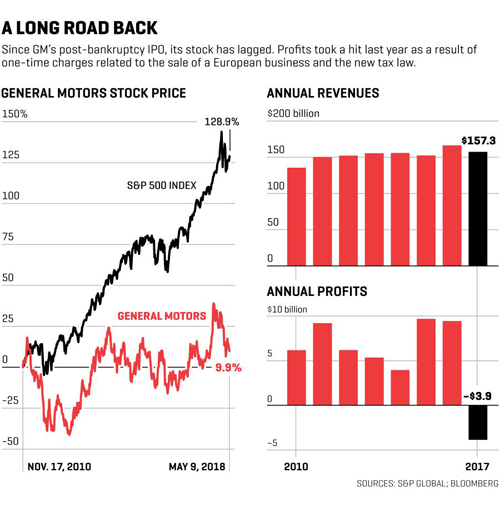

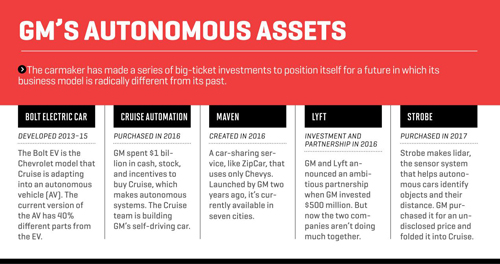

巴拉的问题很合时宜。人们可能轻易会把这家公司想象成工业时代的遗迹,但她的通用汽车面貌绝非如此。77000名领薪员工中,近40%都在公司工作少于五年。“这部分人的加入是自下而上转变的催化剂。”阿里纳说。 年轻员工全新的需求和期望正协助巴拉在全公司上下发动思维的转变。“他们引入的技术和价值,他们在社交媒体方面的专长,都在公司上下产生着深远影响。”巴拉解释道。“一些情况下,实际上是由下至上的状态。” 巴拉也有方法自上而下撬动革新。她带领全公司一同制定了七条行为准则,以引导组织上下所有人的做法——从中国的一位车间工人到巴西的一名营销专员。为了保证“敢想敢做”(Be Bold)、“创新在当下”(Innovate Now)、“让我来”(It’s on Me)以及其他口号不仅仅是口号,她与阿里纳还有人事团队协同整改员工培训,使之侧重于任务导向的设计思维,而少了说教。10月,她提出一项颇具勇气和志向的目标,为所有人设定了几个长期方针:零事故,零排放,零拥堵。 巴拉对这“三零”倡议充满激情。“一百多年来,一直为人们提供交通便利,我们很自豪。”她对我说。“汽车改变了人们的生活方式、工作地点,也促成了城市间紧密联系。它带来一种人们至今仍热爱着的自由。那么,随之而来的有什么?安全隐患、车祸、环境问题,还有堵车的烦恼。有了新技术,我们现在有能力解决这些问题。” 这一计划也为通用汽车公司年轻一代人带来了他们渴求的集体目标意识。“我们知道,如果员工的个人目标与团队的目标不契合,他们在第一年离开的几率就高出86%。”阿里纳说。 当今企业管理方面值得注意的一个趋势是,CEO必须亲自管理人才:员工问题不能再“外包”给人事了。巴拉贯彻了这一点。她将自己的核心角色描述为“制定策略,管控风险,授权他人去执行,以及确保人员负起责任。”她将很大一部分时间花在最后两点上。4月至6月下旬,她将以15或20人为一组,会面公司270位最高主管,讨论他们在推动行为改变方面取得的进展。每个季度,她都会带领14位核心主管进行短期出差,以“关注我们如何建立恰当程度的信任和对未来的共同目标,以及如何应对冲突”。她的人事理念不妨称为“涓滴效应”:只要她与核心团队之间保持公开互信的关系,这些团队成员就可能努力与他们的直接下属建立同样的关系,然后一级一级往下。 但要让这一切都不至落空,巴拉还必须做出清晰、艰难的决策,并实现成果。她也确实一直如此。4月,她解雇了凯迪拉克(Cadillac)总裁,原因是:“我们希望发展的步伐再快一些。”她说。但她最艰难的抉择还是为精简公司规模以期增加利润而做出的一系列举措。巴拉一反几十年来公司对市场份额的渴求,关闭了在印度和南非的运营项目,并将欧宝(Opel)和沃克斯豪尔(Vauxhall)卖给了标致集团(Groupe PSA)——标致汽车(Peugeot)和雪铁龙(Citroën)的母公司。4月,她保留了通用汽车在韩国的项目,但那也是就繁杂的协议与该国多个势力强大的工会重新谈判后才做出的决定。 正是这些决策,加上公司SUV以及轻卡的市场需求,才为通用汽车这家又病又不靠谱、不得不靠政府救助的公司实现了健康发展和持续创收。2015年和2016年,通用汽车汇报利润均超过90亿美元。2017年,由于出售欧宝和沃克斯豪尔的相关费用一次性支付,再加上新税法的影响,公司亏损39亿美元。不过,许多分析人士相当看好通用汽车本年度的前景。前两年北美地区毛利率均超过10%,而公司于各地的利润率目前均在上涨。这样的成就使公司有资格在下一波出行交通浪潮中争抢头筹。“未来每个季度都按照计划做好工作,我们就能做到两者(短期与长期)兼顾。”巴拉说。 斯坦福的奥莱理指出,一家旧时代的公司想要转型以适应新的科技时代,必须做好三个方面:设想、孵化,以及规模化。“每个人都能有所设想,”他对我说。“每个CEO都在创新方面投钱,这也很好。一些企业在孵化阶段做得不错。但难点在于规模化。当你必须将产业和产能从当前可盈利的业务中抽离出来,并投入到利润有限、甚至可能蚕食当前业务的新项目中去的时候,才是真正见分晓的时刻。” 巴拉持相同观点。“我们的资金配置框架表明我们要再次投资于企业,在长期范围内带动股东价值。我们的资产负债表将维持在投资级别。其他的资金,我们将适当回报给股东。”她说。“但首要的支柱,就是我们要为公司的长远发展做新一轮投资。” 通用汽车公司一方面在核心业务中不盈利的项目上削减开支,另一方面为研发自动驾驶的电动汽车提供充裕的资金支持。2016年初,公司投入5亿美元用于Lyft项目——一项被认为比Uber更“友好”的拼车服务。两个月后,通用汽车收购Cruise。去年10月,公司就收购了Strobe。这家11人的初创公司在做的激光探测与测量系统(lidar)能为自动驾驶的汽车分辨障碍物并判断距离。该类系统和汽车蓄电池高昂的成本必须大幅下降,自动驾驶的汽车才能达到与当前汽车相近的售价。 巴拉和通用汽车公司总裁丹·阿曼一直谨慎对待Cruise,唯恐束缚其原有风格,或阻滞了它作为一家初创公司的发展速度。道格·帕克斯是雪佛兰Bolt电动汽车研发工作的领导者,他负责监督通用汽车公司驾驶自动化的工作,并作为关键渠道连接底特律和旧金山。他的部分职责就是确保Cruise不受母公司侵害。“Cruise的人可以来母公司,需要什么就拖走。”巴拉说。“但母公司不能去那边,除非道格·帕克斯知道个中原因。这样,我们既能保证一家初创公司传统的特点,又能让母公司的支持成为他们强大的优势。” Cruise正在大规模招贤纳士,而员工数已从被收购时的40人扩充至现在的500人。其中多数在旧金山一座平凡而不起眼的工业大楼里办公,大楼前拦着一组铁门,8英寸厚,而且看似有保安监控。然而,我造访的时候,外面却没有一人执勤,内部也没人回应对讲机。我在想是否来错了地方。当我看到停车场有几辆白色雪佛兰Bolt电动汽车,车上带着Cruise标志和自动驾驶设备,终于有一名保安过来让我进去。 Cruise确实给人以初创公司的感觉,有各种员工福利:开放空间、谷物食品自助机、鲜有拘束的工作氛围。此外其发展速度看来也确实不愧为一家初创公司。短短两年间,Cruise研发出了四款大幅升级后的Bolt自动驾驶电动汽车。最原始的版本中,Cruise的感应器和电脑由人工栓在车顶,而一些线路仅仅用胶带固定,车也只有最基本的自动驾驶能力。但最新一款车在通用汽车公司一家工厂完成装配:40%的原件都是Bolt自动驾驶汽车独有的配置,此外也除去了方向盘以及其他人工操作。 Cruise和通用汽车公司的高管都认为如此高效的更新证明了两家企业已成功融合。正如其他汽车制造商,通用汽车公司一般需要几年才能研发一款新车,部分原因是每项系统的安全性能都需要反复验证。一款车一旦投入生产,通常在至少一年内不会再去修改。然而,对于Cruise的软件团队,一天发布多项更新是常态。“你得想办法把这两个极端结合起来。”阿曼在一次电话采访中对我说。“表面上看,两个过程完全没有交集,但实际上我们已经找到法子让两方面协同发展。我们造好了自动驾驶汽车的整体构架,使之能适应必要的更新节奏,不管是软件的每日更新、一些部件的每月更新,还是其他部件永久不再更新。” |

Barra’s question is timely. It’s easy to think of the company as a relic of the industrial age, but her GM doesn’t look like that. Some 40% of its 77,000 salaried workers have been with the company less than five years. “That influx is the catalyst for change from below,” says Arena. 2 The different needs and expectations of that younger workforce are helping Barra drive a mindset change throughout the company. “The skills and assets they bring, their expertise in social media, all these things are having a real impact throughout the company,” Barra explains. “In some cases, there’s reverse mentoring going on.” Barra also has levers she uses to drive change from above. She led a companywide effort to define a set of seven behaviors to inform the actions of anyone anywhere in the organization, from a factory worker in China to a marketer in Brazil. To ensure that “Be Bold,” “Innovate Now,” “It’s on Me,” and the others are more than catchphrases, she has worked with Arena and her HR team to shape training sessions that are heavy on task-oriented design thinking and light on exhortation. In October she unveiled an audacious aspirational goal to focus everyone on a set of long-term targets: zero accidents, zero emissions, and zero congestion. Barra is passionate about the Zero Zero Zero initiative. “We’re very proud that we’ve been providing mobility to people for over 100 years,” she tells me. “Cars changed the way people lived, where they work, how cities came together. It gave people a freedom that they still love. Well, what came with that? Safety issues, crashes, environmental concerns, and the frustration of congestion. With the new technologies, we’re now equipped to solve those problems.” The program also provides the kind of collective sense of purpose that GM’s younger generation yearns for. “We know that people are 86% more likely to leave in their first year if their purpose doesn’t align with the purpose of the organization,” says Arena. A noteworthy trend in management circles these days is that CEOs must take charge of their company’s talent: They can’t outsource personnel issues to HR anymore. Barra embodies this. She describes her key roles as “creating strategy, managing risk, empowering people to execute, and making sure we hold people accountable.” She spends a remarkable amount of time on the last two. Between April and late July, she will meet with the company’s top 270 executives in groups of 15 or 20 people to discuss their progress at pushing behavioral change. Every quarter she leads her top team of 14 executives at offsites to “focus on how we build the right level of trust and a shared vision of the future, and on how we manage conflict.” She has what might be called a kind of trickle-down personnel theory: If she works to have an open, trusting relationship with her top team, then those people are likely to put in the effort to have the same with their direct reports, and so on down through the ranks. None of this would matter if Barra didn’t also make clear, tough decisions and deliver results. But she does and has. In April she fired the president of the Cadillac division, because, she says, “We were looking to pick up the pace.” Her toughest decisions, however, have been a set of moves that shrank the company with the goal of increasing profitability. Reversing decades of hungry pursuit of market share, Barra shuttered operations in India and South Africa, and removed the company from Europe by selling Opel and Vauxhall to Groupe PSA, the parent company of Peugeot and Citroën. In April she decided to keep GM in South Korea, but only after renegotiating onerous deals with the country’s powerful unions. Those decisions, combined with demand for the company’s SUVs and light trucks, have turned a sick and unreliable company that the government had to save into a healthy, consistent earner. GM reported more than $9 billion in profits in both 2015 and 2016. For 2017 the automaker took a $3.9 billion loss, thanks to one-time charges related to the sale of Opel-Vauxhall and the new tax law. But many analysts are bullish on GM’s outlook for this year. Gross margins in North America exceeded 10% in each of the past two years, and margins are now rising across the company. That success has earned the company the right to contend for leadership in the next big wave of transportation. “Doing what we’ll say we’ll do quarter by quarter gives us the right to work on both [the short-term and the long-term],” says Barra. Legacy companies trying to make the transition to a new technological era, argues Stanford’s O’Reilly, must succeed at three disciplines: ideation, incubation, and scale. “Everyone ideates,” he tells me. “Every CEO spends money on innovation, and that’s great. Some companies are okay at incubation. But scaling is the hard part. The rubber hits the road when you have to take assets and capabilities away from an existing profitable business and allocate them to new businesses that have lower margins and may cannibalize your existing business.” Barra agrees. “Our capital allocation framework says we’re going to reinvest in the business to drive shareholder value over the long term, we’re going to maintain an investment grade balance sheet, and we’ll return the rest to shareholders in some fashion,” she says. “But the first pillar is that we’re going to reinvest in the business for the long term.” As GM has cut back on unprofitable ventures in its core business, it has put real money behind its effort to develop an autonomous electric vehicle. In early 2016 the company made a $500 million investment in Lyft, the ride-sharing service known for being “nicer” than Uber. Two months later, GM acquired Cruise. Last October it bought Strobe, an 11-person startup that makes the “lidar” laser systems that help an autonomous car identify objects and discern its distance to them. The high cost of lidar systems and electric batteries will have to go way down for AVs to reach price points comparable today’s cars. Barra and GM president Dan Ammann have been careful not to crimp Cruise’s style, or its startup speed. Doug Parks, who led the development of the electric Chevy Bolt, oversees GM’s autonomous efforts and serves as the critical conduit between Detroit and San Francisco. Part of his role is to protect Cruise from the mothership. “People at Cruise can go into the big company and pull out what they need,” Barra explains, “but the big company can’t come in unless Doug Parks knows what’s going on. It’s allowed us to keep the traditional things about a startup while giving them the great assets of a large company.” Cruise has been on a hiring spree and now has more than 500 employees, up from 40 when it was acquired by GM. Most work from an unmarked, nondescript industrial building in San Francisco, behind a set of eight-inch-thick steel gates that are, in theory, monitored by security guards. When I arrive for a visit, however, no one is posted outside, and no one inside answers the intercom. I wonder if I’ve come to the right place. Just when I’m noticing that the parking lot has a couple of white Chevy Bolt EVs with the Cruise logo and autonomous hardware on them, a guard finally comes out to let me in. Cruise does still feel like a startup, with all the trappings: open spaces, cereal dispensers, a visible informality. And it certainly seems to be moving at startup pace. In two years Cruise has developed four significantly upgraded versions of the autonomous Bolt EV. On the first version, the Cruise sensors and computers were bolted by hand to the roof, some wiring was simply taped into place, and the car had only rudimentary autonomous capabilities. The latest version, however, was built in a GM plant: 40% of its parts are unique to the autonomous Bolt, and it has no steering wheel or other human controls. Both Cruise and GM executives point to this rapid iteration as proof that the two companies have successfully integrated. GM, like other auto manufacturers, typically takes years to develop a new car, in part because every system must be validated repeatedly for safety. When that car finally goes into production, nothing typically gets changed for at least a year. The Cruise software team, however, is accustomed to releasing new iterations multiple times a day. “Those are the two extremes you’re trying to bring together,” Ammann tells me in a phone interview. “On the surface, the processes seem completely orthogonal, but we have actually figured out how to have the two things work together. We’ve constructed the whole architecture of the AV to accommodate the necessary rates of change, whether it’s daily on software or monthly on some other components or never on others.” |

|

同阿曼对话的时候,身处布鲁克林(Brooklyn)的我正坐在停着的车内,等待傍晚六点整的到来——那时我就能把车停入泊位而不用收到纽约市警察局的罚单了。这种停车游戏就是传统汽车带来的诸多附属效应中我相当乐意摆脱的一点。 去年11月,驾驶自动化方面的进展终于让巴拉有足够信心做出她迄今为止最大胆的声明:通用汽车公司将在2019年以Cruise汽车的形式发布一款自动驾驶拼车服务,车辆没有方向盘,也没有其他人工操作。公司没有透露该服务将在哪里发布,只说会在美国的某个城市。我问阿曼,Cruise正在绘制曼哈顿中心区域的地图,发布地是否选在了纽约。比如在华尔街附近发布该项服务,或许能刺激公司的股票价格。“我们还没有针对这个问题有所讨论。”他却说。阿曼是新西兰裔,带一种冷静的幽默,他听了会儿又继续说道:“我倒是可以这么说。我们目前相当一部分研究都在旧金山开展,所以——就是说——可以算是一条线索。” 华尔街不厌其烦地追捧行车自动化的各项发布。原因又是什么?多数投资者关注的是长期回报,而在任何一家公司利用自动驾驶载客服务实现可观营业额之前,我们还需等许多年,要创造利润就更遥远了。正如通用汽车公司,奥迪(Audi)、福特、大众(Volkswagen)以及其他汽车生产商也做出了五花八门的承诺,要在某个日期之前将或这或那的自动驾驶服务投入使用。“这些汽车公司大都能‘达成’其目标,”迈克·拉姆齐说。“但影响可能并不大。 说要在2021年之前推出完全自动驾驶的汽车。可万一最高时速只有40英里,并且只能在市中心行驶呢?”与我聊过的通用汽车公司以外的人当中,没有一个相信这家公司能在明年发布任何有分量的相关产品,旧金山也好,其他地方也罢。 我将这些人的说法告诉巴拉,并问她是否担心一旦自己的承诺落了空,公司将会受罚。“我们认为公司正走在正轨上,”她说。“我想,越来越多的人正渐渐明白,研发真正的无人驾驶汽车是相当困难的。我们的技术开发是走在正轨上的。车子的安全性能是我们的一大保障。并且,我们在做我们该做的。当然也有监管的层面,我们也在做相关工作。目前我们仍是不偏不倚,朝这个方向去做,我也相信我们能做到。这是我所要关注的。我不去想‘万一不行怎么办?’——我只关注怎样才能把事情完成。” 这样谨慎地声明了通用汽车公司的决心之后,她笑了笑。总被问到未来怎样怎样,也是相当令人疲惫的一件事吧,我想。 深刻的技术创新需要长时间孕育。所谓“服务型出行交通”(transportation as a service)的发展正处于最坎坷的阶段。最终的愿景很明确,即在全球范围内以安全、共享、自动驾驶的电动汽车取代当前的汽车,从而创造一个事故和污染更少的世界。但明确的目标并不意味着前方清晰的道路。当前,疑问和矛盾远远多于答案。找到这些答案所需要的时间越久,最终的愿景也就离我们越远。 |

While Ammann and I talk, I’m sitting in my parked minivan in Brooklyn and waiting for 6 p.m. to arrive, so I can leave my vehicle in its spot without getting a ticket from the NYPD. The parking game is one of those collateral effects of traditional cars that I’ll be happy to give up. By last November, Barra felt confident enough about the self-driving effort to make her boldest announcement yet: GM would launch an autonomous ride-sharing service featuring Cruise vehicles without steering wheels or other manual controls in 2019. The company didn’t disclose where the service would launch, other than allowing that it would be in a U.S. city. I ask Ammann if New York might be the site, since Cruise is currently mapping downtown Manhattan. A service in, say, the Wall Street area might juice the company’s stock price. “We haven’t commented on this,” he says. Ammann, a Kiwi with a dry sense of humor, pauses for a moment before continuing: “I will say this. We’re doing a significant majority of our testing in San Francisco, and so, you know, there’s a clue.” Wall Street routinely cheers autonomous announcements. But why? Most investors are making long-term bets, and we are years away from anyone generating serious revenue by providing autonomous rides—and even further away from profits. Like GM has, Audi, Ford, Volkswagen, and other carmakers have made an array of promises about having one form of autonomy or another on the roads by a certain date. “Most of these car companies will ‘meet’ their goals,” says Mike Ramsey, “but the impact may not be great. Ford says they’ll have a fully autonomous vehicle by 2021. But what if the top speed is only 40 miles per hour and it’s limited to the urban core?” Nobody I spoke with outside of GM believes the company can launch anything of meaningful scale next year, in San Francisco or anywhere else. I share with Barra what I’ve heard and ask if she worries that the company could be penalized for not delivering on her promise. “We believe we’re on track,” she says. “I think more and more people are understanding the difficulty of developing true autonomous vehicles that take the driver out. We are on track with our technology development. We will be gated by safety. And we’re going to do the right thing. Clearly, there’s regulatory aspects, and we’re working on those. We are still on track, we are still working to that, and I believe that we will. That’s where my focus is. I don’t focus on ‘What if we don’t?’—I’m focused on what will it take to do it.” After that cautious affirmation of GM’s commitment, she smiles, and it occurs to me that it must be exhausting to have people constantly ask you to predict the future. Radical new technologies take time to emerge. The development of what’s come to be called “transportation as a service” is in a particularly frustrating stage. The ultimate vision—a world where safe, shared, self-driving electric cars replace the ones we drive now, making the world safer and less polluted—is clear. But clarity about the destination doesn’t mean there’s an obvious path ahead. Right now, there are far more questions and contradictions than answers. The longer it takes to get those answers, the longer it will take to achieve the vision. |

|

举个例子,不少很有头脑的人物都认为这将会带来巨大的市场。Benchmark的比尔·古尔利是Uber早期的风险投资人,他曾告诉我:“这一市场可能比硅谷追逐过的任何市场都要巨大。”通用汽车公司的阿曼和巴拉都告诉我,这一发展“将改变世界”。Lyft的战略部主任拉兹·卡普尔认为,光是边缘效应就能瓦解价值5万亿美元的产业——他所指的包括汽车保险、贷款、加油站,甚至房地产。(卡普尔指出:“城市14%的房地产都是停车场。未来我们需要一些停车用地,但远不需要这么多。”) 但凭什么认为这些人就是正确的?目前电动汽车产业尚不具备有一定规模并且可持续的市场;Lyft和Uber都在拼命砸钱;而要保障自动驾驶汽车时刻都能安全、可靠地行驶于几乎所有道路,还需要许多年的努力和几十亿美元的投资。“我们不了解的不是技术,”拉姆齐指出。“我们不了解的是这一切是否真正值得。” 于是就产生了这样的疑问:如果一切努力都有了结果,市场价值又在哪里?Lyft和Uber都认为网络是关键。我问卡普尔, Lyft是否像通用汽车公司一样觉得前路充满了各种不确定。“我们觉得是很明朗的,”他回答。“我们不需要去推翻任何一个现有产业——比如一家传统的汽车制造商。汽车销量在减少,人们越来越将出行交通当作服务来消费,这一显著变化已经被证实。我们以为,未来多少也是如此。在美国,当前全部汽车行驶里程中只有0.5%来自拼车公司。我们还有很大的成长空间。” 通用汽车公司和其他汽车制造商持不同意见。“谁掌控了自动驾驶技术,掌控了研发的速度,谁就会处于一个非常微妙的地位,”阿曼说。“我们认为那将会是一个很重要的控制点。” 这些截然相反的观点也解释了为什么通用汽车公司和Lyft之间的伙伴关系——借用一位内部人士的话——“萎缩”了。两家公司已经不在任何项目上协作了。 伙伴关系确实不容易,但也越来越常见——部分原因是,当今的探索一旦产生什么新成果,各个企业就急迫渴望在相关领域站住脚跟。“无马之车”还方兴未艾的年代,就有几百家团体抢着想把生意做起来。通用汽车公司本身就是在这趟风波中由多家企业合并而崛起的。 眼下这场私人出行方式新时代的争霸赛中会出现怎样的黑马?有几位竞争者的出现让人倍感意外。德尔福集团(Delphi Automotive)曾是汽车制造企业的一家主要供应商,后来更名为安波福(Aptiv),开发自己的自动驾驶汽车。谷歌分出Waymo公司,其自动驾驶汽车已在加州行驶超过500万英里。还有中国的百度——一家搜索引擎和科技公司,想要成为自动驾驶汽车界的“安卓”,并已同国内外130多家公司结成联盟。 这一番排兵布阵大概只能算作一场小小的赛前切磋。“市场价值的拔河比赛还没真正开始,”阿曼说道。“等到无人驾驶汽车即将投入使用,好戏才算上演。” 玛丽·巴拉掌舵四年来,成功重塑了通用汽车公司。公司的核心业务蓬勃发展,有势头在未来几年创造丰厚利润——即使自动驾驶汽车登入各大城市早于预期。“我们的核心业务将在相当一段时间内保留其核心地位——向中美洲出售大型卡车,并在能耗和安全性能方面不断优化。 通用汽车公司兼顾核心业务和边缘项目,在两方面都有不俗的发展速度。Bolt电动汽车从模型到生产只花了一年,初次亮相时,充一次电跑了238英里,表现优于预期。此外还有Cruise公司在自动驾驶方面的突破。“你不得不服。两年半以前,没人会谈论通用汽车。这家公司完全无关痛痒,很落后。”另一家自动驾驶行业竞争者的某位主管对我说。 任职早期,巴拉让所有高层主管做了MBTI(Myers-Briggs Type Indicator)性格测试。CEO本人是一位ISTJ,相对的人格类型就是“负责,真诚,善分析,务实,有序,勤奋,可信赖,在实际问题上能做出可靠判断”。看来,通用汽车公司要把握“无马之车”的未来,所需的正是这样的品质。(财富中文网) 本文最先刊载于《财富》2018年6月1日刊。 译者:沈昕宇 |

For example, many very smart people believe this is going to be a huge market. Bill Gurley of Benchmark, an early venture investor in Uber, once told me, “This is probably bigger than any market Silicon Valley has gone after.” GM’s Ammann and Barra both tell me it “will change the world.” Raj Kapoor, chief of strategy at Lyft, believes the side effects alone could disrupt $5 trillion of business—he’s thinking of such things as car insurance, loans, service stations, and even real estate. (Notes Kapoor: “14% of real estate in a city is parking. We’ll need some, but not nearly as much.”) But what proof do we have that these people are right? There currently isn’t a viable mass market for electric vehicles; Lyft and Uber still lose money hand over fist; and it will take years and billions of dollars more investment to get self-driving cars to the point where they are safe and reliable on virtually all roads at all times. “What we don’t know isn’t the technology,” Ramsey points out. “What we don’t know is whether it will all be worth it.” Then there’s this question: If all this effort does pay off, where will the real value lie? Lyft and Uber believe the network is what matters. I ask Kapoor whether Lyft, like GM, sees a lot of uncertainty ahead. “It feels really clear to us,” he says. “We don’t have an incumbent business that is about to be disrupted, like a traditional auto manufacturer. The big change that’s already been documented is people buying fewer cars and consuming transportation as a service. For us, the future is more of the same. In the U.S., just 0.5% of all the vehicle miles traveled are with ride-sharing companies. We have so much room to grow.” GM and the automakers disagree. “The person who controls the autonomous technology, and the rate of development, will be in a very interesting position,” says Ammann. “We think that will be an important control point.” Those diametrically opposed views help explain why GM’s partnership with Lyft has “dwindled,” in the words of one participant. The two companies are not working on anything together now. Partnerships are really hard, but they are proliferating, in part because companies are desperate to secure some kind of foothold in whatever emerges from today’s explorations. In the early days of the horseless carriage, hundreds of outfits vied to establish themselves. General Motors itself rose from that morass, an amalgam of several companies. What beast will come out of today’s scrum to battle for primacy in the new world of personal transportation? There are several unlikely contenders. Delphi Automotive, historically a key supplier to carmakers, has renamed itself Aptiv and is testing its own self-driving cars. Google has spun off Waymo, whose AVs have driven more than 5 million miles in California. Baidu, the Chinese search engine and technology company, wants to become the “Android” of autonomy and has formed an alliance with over 130 companies in China and around the world. It’s likely that all this maneuvering is merely a very preliminary tussle. “The tug of war over value hasn’t started in earnest,” Ammann says. “This starts to get much more interesting when the driverless cars are about to begin operation.” In four years at the helm, Mary Barra has remade GM. The core business is strong and in position to deliver solid profits for years to come, even if autonomous cars arrive in cities sooner than most people anticipate. “Our core business is going to be our core business for a long time,” she says. “Selling full-size trucks to Middle America, with increasingly better performance from a fuel-economy and safety perspective.” GM is moving at an impressive pace, both in the core and on the edge of its business. The Bolt EV went from prototype to production in just one year. It debuted with a better-than-expected range of 238 miles per charge. And then there’s the autonomous progress at Cruise. “You’ve got to be impressed,” one executive at a self-driving competitor told me. “Two and a half years ago, GM was in no one’s conversation. They were totally irrelevant, a laggard.” Early in her tenure, Barra asked all of her top execs to take the Myers-Briggs personality test. The CEO herself is an ISTJ, which the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator describes as, “Responsible, sincere, analytical, reserved, realistic, systematic. Hardworking and trustworthy with sound practical judgment.” It turns out that may be just what General Motors needs to figure out the future of horseless carriages. This article originally appeared in the June 1, 2018 issue of Fortune. |