业绩持续不振,宝洁走向拆分之路?

|

今年10月宝洁举行历史性的股东大会,也经历了公司治理史上规模最大也最昂贵的一场代理权之争,最终双方握手言和。“我们会继续谈,”首席执行官戴怀德(David Tylor)表示,他认为自己稍胜一筹,虽然大概五星期之后详细计票结果显示其实他输了。对此激进投资者纳尔逊·佩尔茨回应称,“‘我们’可以谈,但‘我们’不会听!”(编者注:这里的“我们”指的是宝洁高层领导和董事,佩尔茨用戴怀德的话反讽他)。戴怀德则回应称,“不不不,你说的不对。” 表面上来看,我们看的是一场胜负难分的董事会席位大战,但实际上关系着美国最大企业之一宝洁的命运。现在这场代理权大战结果已揭晓,但特利安基金管理公司的佩尔茨究竟能不能推动宝洁走上巨大变革之路还是未知数。虽然佩尔茨手握35亿美元的股票,多少说话有些分量,但从戴怀德“我们可以谈”的口气就能感觉到,佩尔茨在11或12个人的董事会里必将单打独斗。从两人简短交谈情况也能看出,哪怕只说几句也会因为根本理念不同吵起来,也说明两人对宝洁未来的看法存在巨大的冲突。佩尔茨为了进董事会花了至少2500万美元,宝洁为了阻止他花了至少3500万美元。现在双方终于搁置了争议,但佩尔茨还是进了董事会。 说实话,戴怀德跟佩尔茨在很重要的一点上还是有共识的,就是宝洁需要改。只是两人属意的方式不一样。佩尔茨一直在指责“宝洁持续十年表现不佳。”戴怀德则更强调正面因素,即“我们处于巨大转型过程中。”但背后的现实是宝洁已持续低迷多年。 |

At the end of Procter & Gamble’s historic annual shareholders’ meeting in October, the climax of the biggest, most expensive proxy fight in corporate history, the two antagonists shook hands. “We’ll talk,” said CEO David Taylor, who thought he had won by a slim margin, though a careful count of paper ballots showed some five weeks later that he’d lost. To which activist investor Nelson Peltz replied, “We’ll talk, but we don’t listen!” (the “we” referring to P&G’s top leaders and directors). Taylor responded, “No, no, no, that’s not true.” And there we have in microcosm the surprisingly inconclusive outcome of a bitter battle ostensibly over a single board seat, but in reality over the future of one of America’s greatest companies. We know who won the proxy fight, but we have no idea whether Trian Fund Management’s Peltz will succeed in his campaign for major change at P&G. Though his $3.5 billion of company stock gives his views extra heft, as Taylor’s “We’ll talk” indicates, Peltz will be only one director on a board of 11 or 12. The two men’s brief conversation suggests they can’t exchange even a few words without disagreeing fundamentally—reflecting the larger conflict between their sharply different views of P&G’s future. Peltz spent at least $25 million to get himself elected to the board, and P&G spent at least $35 million trying to keep him off. Now they’ll resume their dispute, but with Peltz in the boardroom. Truth be told, Taylor and Peltz agree on one big thing: P&G needs fixing. They spin it differently. Peltz rails about “P&G’s decade-long history of underperformance.” Taylor sells the upside—that “we’re in a major transformation.” But the underlying reality is that this company has been sputtering for years. |

|

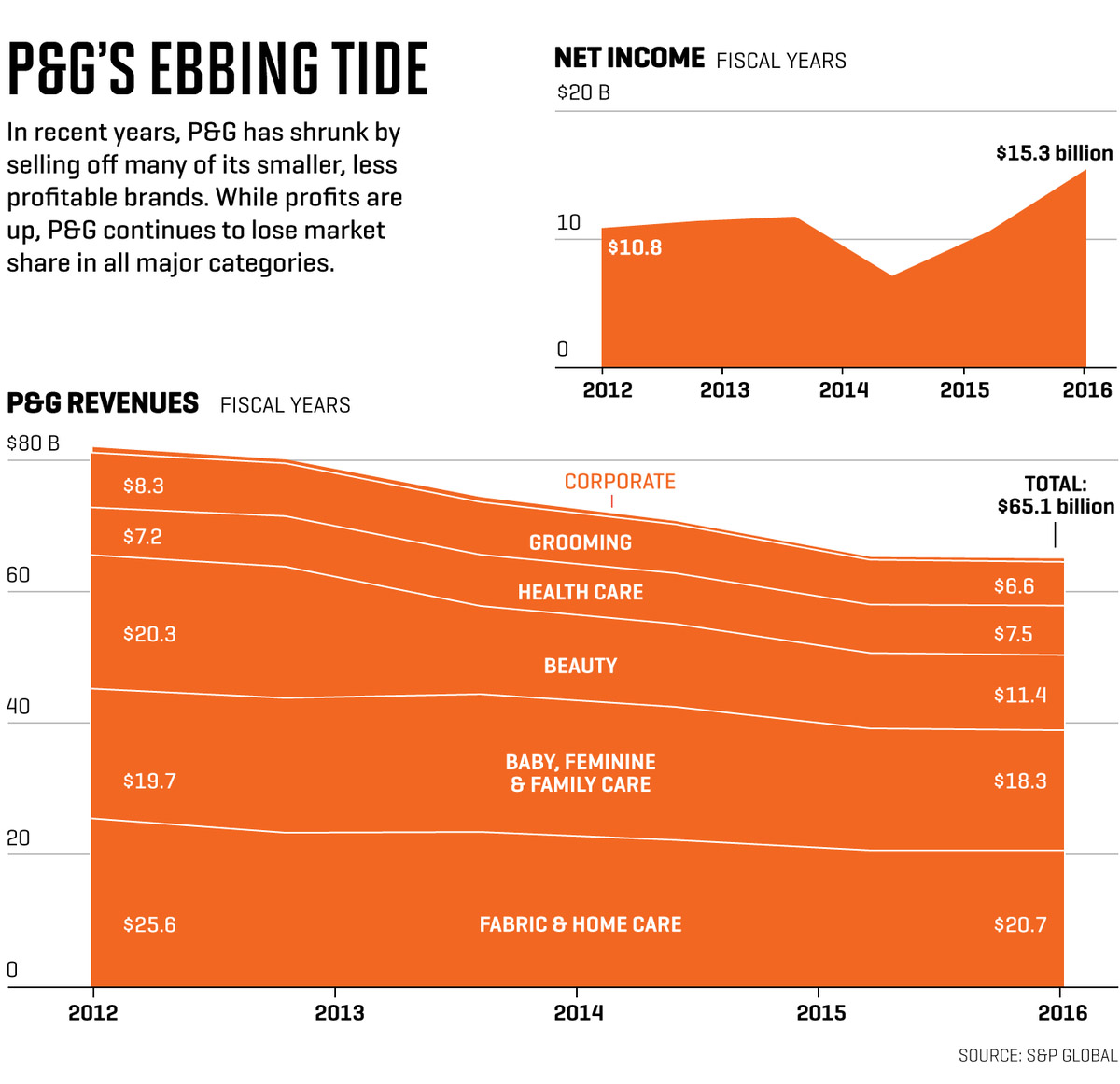

宝洁的问题不只是业务低迷。之前我们也见过类似情况,即鼎盛的美国企业仿佛过了气,面临着追回往日荣光还是步入长期衰退的问题。大概25年前,IBM、通用汽车、希尔斯和柯达也面临过类似的转折点。重返高峰并非不可能,IBM就做到了,至少有段时间做到了,但历史经验证明机会真的很小。戴怀德现在59岁,纳尔逊·佩尔茨75岁,两人都很清楚自己在做什么,虽然策略相差很大。所有证据都表明,至少未来几年里两人都会坚持自己的计划。所以就要看,到底谁能拯救公司? 首先分析下挑战的难度。自从美国经济达到衰退前顶点以来,宝洁的股价(也包括股利)表现一直比标普500指数企业平均水平差。随着大众消费品整体增速放缓,行业内最大的巨头宝洁也渐渐落在竞争对手身后——包括联合利华、高露洁、德国汉高等等。宝洁旗下很多大品牌,包括吉列、佳洁士和潘婷市场份额都在下跌。过去一个财年里(截至6月30日)五大主要品类市场份额都出现大幅下降。上个财年里自然增长率,即不考虑收购、剥离资产和外汇兑换等因素的增长率仅为2%,预计今年增长率为2%至3%。该数字低于大部分竞争对手,如果算上通胀调整因素的话,宝洁实际自然增长率几乎为零。 数字看起来很差,非财务指标则更不妙。现在的年轻人找工作时,宝洁的吸引力远比不上过去。一位宝洁出身的人士就对其如今的颓势非常难过,他回忆道,“我进公司的时候,宝洁就像现在的谷歌和亚马逊,是当时最光鲜的地方。让人感觉‘我们是全世界最强的企业,我们的产品是最好的,我们改善人们的生活,而且培养出全世界最优秀的领导者。’想进宝洁非常难。面试的时候就会镇住你。当时公司真的很强。现在再也没有那样的气势了。” 数据也能证明这点。1996年《财富》杂志调研企业领导、董事会成员和股票分析师排出年度榜单里,宝洁是美国最受尊重的企业(仅次于可口可乐)。2009年,宝洁还能排第六,之后一路下滑,如今已经落到第19名,就在佩尔茨发动代理权大战之前做的调研。 当然了,对很多企业来说,能在全世界最受尊重的企业榜单上排名第19,市值2200亿美元,还能当上道琼斯成分股已经很不错。这些都是成功的标志,但也孕育着巨大的问题,因为可以得出以下结论:宝洁没有遇到危机。如果屈从惯性思维,宝洁完全可以像所有走下坡路的企业一样安慰自己,只想着维护现状,不用太考虑趋势。宝洁可以列举出在各个国家做得非常好的产品当证据。然而事实摆在眼前,刚刚结束的三年里,董事会给高管层定下的指标都没有完成。接下来的三年,董事会称自然增长率要达到年均2.8%,虽然戴怀德表示市场增速可能为3%到3.5%。感觉就是落水之人勉强挣扎而已。正如一位宝洁前高管总结的,“按他们制定的目标,市场份额只会越来越低。” |

P&G (PG, +1.16%) isn’t just a business in the doldrums. It’s in a troubling situation we’ve seen before—an aristocrat of American enterprise seemingly past its prime, now facing the profound question of whether it can regain lost glory or continue into a long, slow decline. IBM, General Motors, Sears, and Kodak were at that same turning point about 25 years ago; some would put General Electric in that category today. A comeback isn’t impossible—IBM did it, for a while at least—but history says the odds are heavily against it. David Taylor, 59, and Nelson Peltz, 75, both think they know what needs doing, though their strategies are radically different. All evidence suggests they’ll both remain on this project for a long time to come, maybe several years. So who, if either, can save this company? Consider the magnitude of the challenge. Since the U.S. economy’s pre-recession peak, P&G stock (including dividends) has badly underperformed the S&P 500. As the whole consumer packaged goods business slows down, P&G, the industry’s biggest player, has been falling behind major competitors—Unilever, Colgate-Palmolive, Henkel, and others. Dozens of major P&G brands, including Gillette, Crest, and Pantene, have been losing market share; all five of its product categories lost significant share in the past fiscal year (ended June 30). Organic growth, a company-calculated measure that strips out the effects of acquisitions, divestitures, and foreign currency translation, was just 2% last fiscal year, and the company forecasts 2% to 3% this year. Those numbers are below most competitors’, and since they aren’t adjusted for inflation, they mean P&G’s actual organic growth is around zero. The numbers are damning, and nonfinancial indicators are even more ominous. Today’s best young people might never imagine that P&G was once as glamorous an employer as any company in the world. An alumnus, one of many distressed by its slide, recalls, “When I joined, it was the Google, the Amazon, the Goldman of its day. Its message was, ‘We’re the best company in the world. We create the best products, we improve people’s lives, we export great leaders to the whole world.’ It was hard to get into. They crushed you in the interviews. It was just great. They don’t have that edge anymore.” Data supports the assertion. Back in 1996, P&G was America’s second-most-admired company (after Coca-Cola) in Fortune’s annual survey of corporate leaders, board members, and stock analysts. As recently as 2009, it was the sixth-most-admired company in the world. It has been falling steadily since, today ranking 19th based on a survey conducted before Peltz launched his proxy fight. Of course most companies would be thrilled to rank 19th among the world’s most admired, to boast a market cap of $220 billion, to be a Dow component. These are the marks of a champion—and that’s a big problem, which can be summarized as follows: P&G is not in crisis. It can, if it succumbs to the temptation, console itself the way declining organizations have always consoled themselves, by focusing on its current state rather than on the trends. It can point to a hundred ways in which it’s doing well with various products in various countries. The fact remains, however, that the company missed most of the targets the board set for top executives in the just-ended three-year performance period. For the next three-year bonus period, the board declared an organic growth target of 2.8% a year, though Taylor has said he expects market growth of 3% to 3.5% a year. That’s barely treading water. As one former P&G executive sums up, “They set a goal to lose market share.” |

|

文化不再是加速器,反而成了制动闸。 宝洁称四年前就意识到挑战存在,从那时起就开始转型。戴怀德发誓大力推动,举措之一就是引入更多外部人才加入高层。很有道理,但会陷入第22条军规的困境:宝洁的企业文化向来拒绝外来者,基本只招聘初级员工,原因就是再往上级别的外人就没法接受企业文化。近年来宝洁通过收购引入了部分外人,但很少有管理层能留下。“宝洁文化排斥他们,”一位前高管称,他口中的“宝洁文化”是指完全同化的宝洁员工。实际上,佩尔茨说戴怀德在去年春天一次会上告诉他,“我们没法请层级较高的外人,他们肯定待不下去。”宝洁并未否认这句话,只是表示单独看有些断章取义。一位发言人列举了几位外部请来的高管,但外部人士还是极少。总体来看,宝洁称去年从外部聘请了200位初级以上员工,几年前还只有50位。 然而,聘请外部人士由内部高层领导没什么用。“光是招聘销售人员改变不了文化,”1998年至2008年曾担任首席执行官的克莱顿·达利表示,他现在跟佩尔茨合作。“宝洁得从外部聘请高管才行。如果过去十年美妆业务没起色,为什么不从欧莱雅或者联合利华挖人呢?” |

P&G claims it recognized the challenge four years ago and has been transforming its culture since then. Taylor vows to turbocharge the change, in part by bringing in more outsiders at high levels. Makes sense, except for a perfect catch-22: The culture has a long history of rejecting outsiders brought in much above entry level—because they don’t understand the culture. P&G has brought in hordes of outsiders over the years through acquisitions, especially its biggest one, Gillette, but few executives remain. “The Proctoids rejected them,” recalls a former exec, using the term for thoroughly acculturated employees. In fact, Peltz says Taylor told him at a meeting last spring that “we cannot bring in outside people at too senior a level or they will fail.” P&G doesn’t deny the quote but says it was taken out of context. A spokesman points to several senior staff executives who have been brought in from outside, though few high-level line managers are outsiders. Overall, P&G says it brought in 200 outsiders above entry level last year, up from 50 a few years ago. Yet bringing them in below senior levels achieves little. “You don’t change the culture by hiring salespeople,” says Clayton Daley, the company’s CFO from 1998 through 2008, who is now working with Peltz. “The company must hire senior line management from the outside. If your beauty line has been suffering for a decade, why wouldn’t you want to get someone from L’Oréal or Unilever?” |

|

还有一点很重要,跟企业文化也差不多,就是组织架构。宝洁内部一直像个大迷宫,布满各种枝枝蔓蔓,如果画出来可能就像东京地铁图一样复杂。几十年来,宝洁首席执行官以下没有一个人全盘掌控过,或者负责过盈亏。既然没有责任,业绩也就没有那么重要,人们更愿意逃避。佩尔茨称现在仍是如此,但戴怀德表示在简化“复杂架构”,就是内部周知几乎不可穿透的组织结构。他让业务部门负责人“全盘”负责盈亏,虽然相关负责人对支出和推广决策并不能全面掌控。在小一些的市场里,团队可以“在一定框架内自由决定”支出和定价。与此同时,戴怀德也将业绩奖金发放权下移,鼓励更多担责。这是个过程。至于够不够还有待观察。 如果戴怀德真能理顺企业文化和架构,就有机会解决宝洁最头疼的问题之一:创新文化衰退。宝洁有全球闻名的两板斧,一是经过多年研究发明新产品,二是打造强势品牌并大力推广。最突出的例子就是汰渍,这是世界上第一个合成洗衣粉,也是最畅销的洗衣粉,仅2017年预计销售额就超过60亿美元。 但突破性创新和新的强势品牌现在越来越少了。宝洁最近两个大突破是速易洁产品线下的拖把、清扫机、抹布等产品,另一个就是纺必适系列家庭除臭剂,都是1998年研发的。(2012年推出的汰渍洗衣丸是很成功的品牌延伸。)为了回应质疑,戴怀德还引入了“精简创新”系统,现在很多公司都在积极应用。这也是个好主意,只要企业文化能容下就行。 更重要的是戴怀德承认了宝洁存在问题,还表示正在积极解决。他引用了股价为证,在图A可以看到。他担任首席执行官两年来,宝洁股价加股利已经回升20.4%,还是比不上标普500的23%涨幅。业绩平平可能没什么好吹嘘,但比起之前两年表现已经好多了。 问题在于,最近股价表现回升部分原因是佩尔茨的积极参与,还有他作为激进投资者擅长提升公司业绩的名声。2月佩尔茨宣布持股时股价上升,6月传出佩尔茨提名自己加入董事会时股价上扬幅度更大。不管宝洁愿不愿意接受,佩尔茨还是帮了忙,然后宝洁又用股价上扬为自己辩解。 此外,宝洁为了支撑股价也使用了不少财技。上次公布收益情况时,宝洁骄傲地称上一季度持续经营每股收益增幅达5.8%。但只要深挖一点就能发现实际上持续经营每股收益没有增长。宝洁只是回购了不少股份,所以每股收益数字看上去涨了。如果看过去四个季度也差不多: 持续经营每股收益上升6%,但根本原因是股份数降低;实际持续经营每股收益只上升了0.6%。 用小招数提升每股收益并不能提升公司价值。最后还是要借来数十亿美元还给股东,公司资本结构改变,但对业绩毫无影响。这种做法本身并无问题。多年来宝洁一直在回购股票。但十年前二十年前实际年增长率能达到10%甚至更多,回购只会小幅影响收益情况。现在却成了提升持续经营每股收益唯一的手段。 这种行为并不可持续,宝洁自己也打算收手,表示希望本财年通过“核心业务利润增长”,而不是通过股份回购,“推动核心业务每股收益增长”。与此同时,宝洁还承诺以股利形式向股东发放更多现金,很多股东都非常虔诚地多年追随。127年来宝洁每年都派发股利,而且61年来持续提升。“我们现金的主要用途就是派发股利,”宝洁在提交美国证券交易委员会的文件中称。此举并无错,但前提是不要影响将钱用在更有效率的地方,比如收购创新型新品牌,毕竟竞争对手都在这么做,佩尔茨就很支持收购。过去四个季度里,宝洁的现金流超过100%以股份回购和股利形式流回股东手中。 实际上,戴怀德的转型计划是渐进的,虽然用的语言比较激进,说什么打造“面目全新的企业。”像大多数需要创新的优秀老企业首席执行官一样,他似乎最担心催得太紧导致崩溃。这可以理解,但像宝洁一样文化根深蒂固的企业其实非常善于排斥根本性变化。佩尔茨的计划显然更激进,但比起他对其他企业的手段还是比较克制,对宝洁他比其他激进投资者更注重长期发展。他都没有建议换掉戴怀德,也没提削减研发计划或发债。 有些投资者称,不管是戴怀德还是佩尔茨都没搞清宝洁真正的问题。他们认为唯一的解决方案就是激进投资者(包括佩尔茨)经常提出的建议:拆分公司。 桑福德·C·伯恩斯坦公司明星分析师阿里·迪巴迪最近被《机构投资者》评为全美顶尖研究团队,近两年他一直呼吁拆分宝洁。“我认为戴怀德为了宝洁已经拼劲全力,”他表示。“不幸的是,宝洁十年前就应该大转型。我相信对股东来说拆分仍然是最佳选择。” 大企业总是称通过结合多项业务可以实现价值协同和规模经济,但迪巴迪表示所谓的优势“看来不过是幻觉。”大企业拆分出来的品牌,例如宝洁卖给科蒂的美妆品牌(伊卡璐、威娜、封面女郎等等)在小集团里活得一样很好。“如果仔细算算利润和成本的话,宝洁并不比规模小些的竞争对手更高效。反而更复杂。对当下的宝洁来说是并无协同效果的规模经济。” 宝洁内部人士怀疑,虽然佩尔茨没有提到拆分,但私下里可能也在考虑。他希望宝洁重整10项全球业务部门,变成“一家简洁高效控股公司”旗下三家“独立”业务。从这种架构走向拆分只是一步之遥。总部位于英国的利洁时是宝洁竞争对手之一,旗下有来苏儿和护丽洗涤剂等品牌,最近宣布明年1月1日起将采用精简架构(分成两个部门而不是三个),分析师推测此举是为全面拆分铺路。 分拆可能会推动创新和提升效率。但现在来看除非业绩进一步下滑,否则可能性并不大。不管对宝洁来说最佳方案可能是什么,业绩都是最大的问题,因为业绩下滑是缓慢衰退的根本原因。大型成功企业跟不上变化时很少会突然倒闭,更常见的是停滞不前。这些企业也会改,但力度不够。他们也会制定策略解决问题,但效率不高,要么就是没法执行。“我最担心的是他们把自然销售增长率提升回3%的水平,然后宣布转型成功,”一位前宝洁员工表示。不过宝洁坚称其雄心壮志不会这么小。 两年前的年度股东大会上,就在戴怀德出任首席执行官几个星期前,一位名叫凯伦·梅耶尔的股东问当时即将卸任的首席执行官雷富礼,“您如何向我这样的股东保证,曾将企业带入泥潭的主管和负责人能成功将企业拽出泥潭?”今年的股东大会上,凯伦的丈夫彼得提醒了戴怀德这个问题,还给出了自己的答案:“从当前的数据看答案已经很明显。他们做不到。” 彼得这个答案也不一定对。戴怀德再次肯定了近几年全公司付出的艰苦努力,向梅耶尔保证领导者和董事们都在努力追求优秀的业绩。即便宝洁无法重现往日荣光,也可以说戴怀德获得了成功。“我认为宝洁成不了未来的谷歌或亚马逊,”迪巴迪表示,“但为了股东宝洁也得奋起。” 然而,凯伦·梅耶尔的问题到现在仍有意义,未来几年就能得出分晓。现在宝洁还在努力挣扎没有彻底没落,对改变的需求虽然强大但还没到生死关头,也正是做出关键决策影响命运的时刻。宝洁并没有出现危机。很快我们就会知道宝洁是不是真的需要来一场危机来推动变革。但如果真到那一步,恐怕为时已晚。(财富中文网) 本文另一版本将发表于2017年12月1日出版的《财富》杂志,标题是《宝洁是不是该拆分了?》本文已根据最新消息更新。 译者:Pessy 审校:夏林 |

Closely related, and just as important, is the organizational structure, which at P&G has long been impossibly Byzantine, a sprawling matrix of dotted lines that would look like a map of the Tokyo subway if anyone charted the whole thing. For decades, virtually no one below the CEO held full control and responsibility for any profit-and-loss result. And without accountability, performance became less important than blame-shifting. Peltz says it’s still that way, but Taylor says he is thinning “the thicket,” as the near-¬impenetrable structure is known internally. He has given business unit heads “end-to-end” responsibility for profit and loss, though they still lack full control over spending and marketing decisions. In small markets, teams have “freedom within a framework” to control spending and pricing. Accordingly, Taylor is extending performance bonuses further down into the organization to enforce accountability. That’s progress. Whether it’s enough remains to be seen. If Taylor can fix the culture and structure, he has a shot at reversing one of P&G’s most vexing problems: the decline of its vaunted innovation machine. The company was long the world’s greatest at the twin skills of creating new consumer products, often after years of scientific research, and then building superpowerful brands under which to market them. The outstanding example is Tide, the first synthetic detergent and the global bestselling detergent by a mile with estimated 2017 sales of over $6 billion. But breakthrough innovations and new blockbuster brands have been getting rarer. P&G’s last two major hits were the Swiffer line of mops, sweepers, dusters, and related products, and the Febreze brand of household odor eliminators, both introduced in 1998. (Tide Pods, introduced in 2012, have been a highly successful brand extension.) Taylor is responding in part by introducing the “lean innovation” system, which many companies are using enthusiastically. It’s another good idea—if the culture doesn’t reject it. More broadly, Taylor acknowledges P&G’s problems and says the company is fixing them. Exhibit A in his argument is the stock price. In the two years since he became CEO, P&G stock including dividends has returned 20.4%, not quite matching the S&P 500’s 23%. Middling performance may not seem like much to crow about, but it’s a great deal better than the stock had been doing over the previous two years. The trouble with this argument is that at least some of the stock’s recent vim is a response to Peltz’s involvement and his reputation as an activist who spurs better performance. The stock price jumped in February when Peltz disclosed his stake, and it jumped even more in June when word leaked that Peltz had nominated himself for the P&G board. The company seems to be getting help from Peltz whether it wants it or not, then citing the stock’s rise in its own defense. In addition, P&G has been performing financial acrobatics to buoy the stock. The company reported proudly in its latest earnings release that earnings per share from continuing operations had risen a respectable 5.8% in the most recent quarter. But a bit of digging shows that actual earnings from continuing operations hadn’t risen at all. P&G simply bought back a large number of shares, so the per-share number increased. It’s a similar story over the past four quarters: Earnings per share from continuing operations rose 6%, but virtually all of that increase merely reflects a shrunken share count; actual earnings from continuing operations rose just 0.6%. Increasing EPS in this way does not make the company more valuable. It returns billions of dollars, much of it borrowed, to the shareholders, and the company’s capital structure changes, but that change has no effect on operating performance. There’s nothing improper about any of this. P&G has been buying back stock for many years. But a decade or two ago, when actual annual earnings growth reached 10% or more, buybacks added just a smidgen of extra EPS. Now they’re virtually the only source of increased EPS from continuing operations. That practice isn’t sustainable, and the company plans to scale it back, saying it expects “core operating profit growth”—not share buybacks—“to be the primary driver of core EPS” this fiscal year. At the same time, it has promised to send even more cash back to shareholders in the form of dividends, to which it is almost religiously devoted. The dividend has been paid annually for 127 years and increased annually for 61 years. “Our first discretionary use of cash is dividend payments,” P&G states in an SEC filing. That’s fine unless it interferes with more productive uses of money, such as the acquisition of innovative new brands, a move that competitors are making and that Peltz advocates. Over the past four quarters, P&G has sent more than 100% of its free cash flow back to shareholders via share buybacks and dividends. The truth is that Taylor’s transformation plan is incremental, despite the bold language about creating “a profoundly different company.” Like most insider CEOs of great, old companies in need of renovation, he seems concerned about breaking the organization by pushing too hard. That’s understandable, but cultures like P&G’s are astoundingly effective at repelling fundamental change. Peltz’s plan certainly pushes harder, yet it’s restrained, even by comparison with his own proposals at other companies, which have typically been more long-term-oriented than other activists’. He is not suggesting that Taylor be replaced or R&D be cut or debt be taken on. Some investors argue that neither Taylor nor Peltz understands how troubled P&G really is. They say the only solution is a remedy that activists (including Peltz) have often demanded elsewhere: breaking up the company. Ali Dibadj, a star analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein who was recently named to Institutional Investor’s All-America Research Team, has been advocating a breakup for over two years. “I think David Taylor is doing his best to change the company,” he says. “Unfortunately, he’s been given a company that should have been changed 10 years ago. I believe breaking up is still the best option for shareholders.” Big companies argue that they achieve valuable synergies and economies of scale by combining many businesses, but Dibadj says those advantages “appear to be illusory.” Brands that giant companies divest, such as the beauty brands (Clairol, Wella, Covergirl, and others) that P&G sold to Coty last year, do just as well in smaller organizations, he says. “If one does the math on their margins and costs, and compares with smaller competitors, P&G is not more lean. It’s more complex. There are dissynergies of scale for P&G at this point.” P&G insiders suspect that while Peltz hasn’t called for a breakup, he may secretly favor one. He wants P&G reorganized from 10 global business units into just three “stand-alone” businesses within “a lean holding company.” From that structure to a breakup would be only a small step. A P&G competitor, U.K.-based Reckitt Benckiser, marketer of Lysol, Woolite, and other brands, recently announced it will adopt just such a structure (with two parts rather than three) as of Jan. 1, and analysts speculate the move was a prelude to full separation. A breakup might well unleash waves of innovation and productivity. But for now, it looks unlikely to happen unless performance gets much worse. That’s a problem regardless of what the best solution for P&G may be, because it supports the slow-decline scenario. Big, successful incumbents rarely flame out when they fail to adapt. More often they stagnate. They change, but not enough. They usually have a strategy for addressing their issues, but it isn’t sufficient, or they can’t execute it. “My biggest fear is that they’ll get organic sales growth back to 3% and will declare victory,” says one alum. P&G insists its ambitions are far greater than that. At the annual shareholders’ meeting two years ago, a few weeks before Taylor took over as CEO, a shareholder named Karen Meyer asked outgoing P&G chief A.G. Lafley, “What assurance can you give me, the shareholder, that the officers and directors who drove the company bus into the ditch are the ones to get us out?” At this year’s meeting, her husband, Peter, reminded Taylor of that question and then gave his own response to it: “I think the answer has been made abundantly clear by the current data. They can’t.” That answer may not be correct. Taylor, repeatedly acknowledging the company’s travails of the past several years, assured Meyer that the leaders and directors are utterly committed to outstanding results. And Taylor can succeed even without returning P&G to its full former glory. “I don’t think it can be the Google or Amazon of tomorrow,” says Dibadj. “But it owes it to shareholders to get better.” Nonetheless, Karen Meyer’s question is undoubtedly the right one, and the answer will become clear in just the next couple of years. Now, when P&G is treading water but not sinking—when the need for change is powerful but not desperate—is when this great institution’s fate is being determined. Procter & Gamble is not in a crisis. We’ll know soon whether it requires one in order to make the needed changes. If it does, it will be too late. A version of this article appears in the Dec. 1, 2017 issue of Fortune under the headline “Is It Time for P&G to Break Up?” The story has been updated to reflect breaking news. |