与优步CEO一起搭车,看他是不是个混蛋

|

无论你是爱他的无畏野心,还是恨他的铁石心肠,特拉维斯•卡兰尼克都是一位长期霸占头条新闻的公司恶棍。自从优步率先通过一个简单的智能手机应用,将寻求打车的都市人与司机相互连接以来,他坐镇旧金山总部运营的这家私人公司已经成为一种全球性现象。2016年,现在进驻76个国家的优步提供了价值200亿美元的出行服务,斩获65亿美元营收。就在这项业务蓬勃发展之际,这家初创公司的投资者继续在卡兰尼克的创作上押下重注。到目前为止,该公司已筹集170亿美元债务和风险投资,并令人咋舌地获得高达690亿美元的估值。与此同时,卡兰尼克本人则变得臭名昭著。在许多人看来,他是一位自以为是,蔑视任何成功法则,不择手段追求胜利的企业家;作为优步的大男子主义者统帅,他催生了一种充斥着性别歧视的企业文化。 在即将出版的新书《狂野之旅:探究优步称霸世界的秘密》(Wild Ride: Inside Uber’s Quest for World Domination)中,《财富》执行主编亚当•拉辛斯基重述了这家公司令人震惊的崛起过程,以及它一路走来遭遇的种种非议。他讲述优步故事的征程,也经历了一个颠簸动荡的开始:在这本书还没有动笔之前,卡兰尼克最初威胁要击沉拉辛斯基的写作计划,他授权另一位作家撰写传记。随着时间的推移,卡兰尼克终于大发慈悲,同意合作,拉辛斯基对他和其他优步高管进行了数小时的访谈。在你即将先睹为快的摘录中,拉辛斯基与他一起漫步旧金山街头,试图搞清楚这位CEO面临的一个纠缠不休的问题:公众对他的看法是否符合现实?他真的是个混蛋吗? 尽管时钟已指向晚上7:30,但旧金山的夏日骄阳仍然普照大地。我准时抵达优步公司总部,准备对CEO特拉维斯•卡兰尼克进行一场内容广泛的采访。鉴于优步向来以工作时间长著称,看到办公室只有零零散散的几个人时,我多少有点惊讶。现在是七月中旬,年轻的员工们或许正在外面享受人生。但也有可能是因为,这家公司的员工团队正在松弛身心——到了2016年的这个时点,历经超过五年的全速飞驰之后,他们想必早已疲惫不堪。 卡兰尼克本人掌控着优步的节奏。再过几天,他将迎来自己的40岁生日。在很大程度上,他仍然过着一位年轻创业者以咖啡因驱动的生活方式。多年来,他一直有固定的女友,但他始终恪守单身主义。多位朋友透露说,不工作的时候,卡兰尼克其实挺恋家的,但他对优步的忠诚度显然要远大于其他任何关系。 预约时间过了几分钟后,卡兰尼克来到他的办公桌旁。我正在那里耐心等候。他在这层楼的远端有一个私人角落,在那里留存着几件衣物,以及一个优步新总部的立体模型——这栋位于使命湾的新总部预计将于2019年投入使用。NBA劲旅金州勇士队正在这条街道的对面建造一座新球馆。卡兰尼克其实并不怎么坐,他的开放式办公桌位于该公司四楼主办公室,一点都不花哨,更谈不上“角落办公室”。 对卡兰尼克、他以前的公司和优步进行了长达一年的研究之后,我深知此次采访需要保持灵活性:他喜欢无拘无束,或者至少喜欢摆出一副率性而为的样子。我们事先并未讨论采访议程,只是说我们将继续谈论一个月前在中国展开的话题:他的职业生涯。他告诉我,开始访谈前,他有一些东西想展示给我看——如果我愿意接受一个非常规建议的话。 “好的,你有两个选择,”他宣布。“我们可以去那个房间。”他指向附近的一间会议室,这是优步进行私人谈话的众多会议室之一。“我会在那里一直来回走动。或者我们可以出去散步。” |

Love him for his audacious ambition or hate him for his tone-deaf ruthlessness, Travis Kalanick is a headline-grabbing corporate villain for the ages. Uber, the privately held company he runs from his base in San Francisco, has become a global phenomenon in the mere six years since it first began connecting ride-seeking urbanites with drivers via a simple smartphone app. Now operating in 76 countries, Uber booked $20 billion worth of rides worldwide in 2016 and brought in $6.5 billion in revenue. As its business has boomed, the startup’s investors have continued to bet big on Kalanick’s creation. To date the company has raised $17 billion in debt and venture capital, and has been accorded a gargantuan market value of $69 billion. At the same time, Kalanick himself has become infamous—seen by many as a brash, win-at-all-costs entrepreneur who’ll flout any rule to succeed, as well as a bro-in-chief enabler presiding over a sexist corporate culture. A new book by Fortune executive editor Adam Lashinsky, Wild Ride: Inside Uber’s Quest for World Domination, recounts the company’s stunning rise—and its headlong plunge into controversy. Lashinsky’s quest to tell the Uber story got off to a bumpy start: Kalanick at first threatened to torpedo his project before it started by hiring a competing author to write an authorized account. Over time, Kalanick relented and agreed to cooperate, and Lashinsky conducted hours of interviews with Kalanick and other Uber executives. In the following excerpt, Lashinsky walks the streets of San Francisco with Kalanick as the CEO confronts a nagging concern: Does the public’s perception of him match reality? Is he really an asshole? I. It is 7:30 p.m. on a sunny summer evening when I arrive at Uber’s San Francisco headquarters for an extended interview with CEO Travis Kalanick. I’m a bit surprised to see so few people in the office, given Uber’s reputation for long hours. It’s mid-July, so perhaps the young staff is out enjoying itself. But it is also possible the company’s workforce is mellowing—fatigued, by this point in 2016, from more than five years of galloping at breakneck speed. Kalanick himself sets the pace. He’s just days away from his 40th birthday and still very much leading the young entrepreneur’s caffeine–fueled lifestyle. Over the years he has often had a steady girlfriend, but has remained resolutely unmarried. Multiple friends describe Kalanick as something of a homebody when not working, yet far more committed to Uber than to any other relationship. A few minutes past the appointed hour, Kalanick arrives at his desk, where I’m waiting. He has a private nook at the far end of one floor, where he keeps some clothes as well as a diorama of Uber’s new headquarters under construction in the Mission Bay section of town. (Scheduled to open in 2019, Uber’s new HQ will be across the street from where the Golden State Warriors basketball team is building a new arena.) But to the extent that Kalanick sits, which isn’t much, it is at an open-plan desk at the edge of the company’s fourth-floor main offices. There’s nothing fancy or “corner office” about it. After a year of researching Kalanick, his past companies, and Uber, I know enough to be flexible: He likes to play it loose, to at least affect an air of spontaneity. We haven’t discussed our agenda ahead of time other than that we’ll continue the conversation about his career that we began a month before in China. He tells me he has a few things he wants to show me before we start talking—that is, if I’m willing to accept an unconventional suggestion. “Okay, you’ve got two choices,” he announces. “We can go in that room,” he says, pointing to a nearby conference room, one of many at Uber used for private meetings, “and I’m going to fucking pace back and forth the entire time. Or we can go for a walk.” |

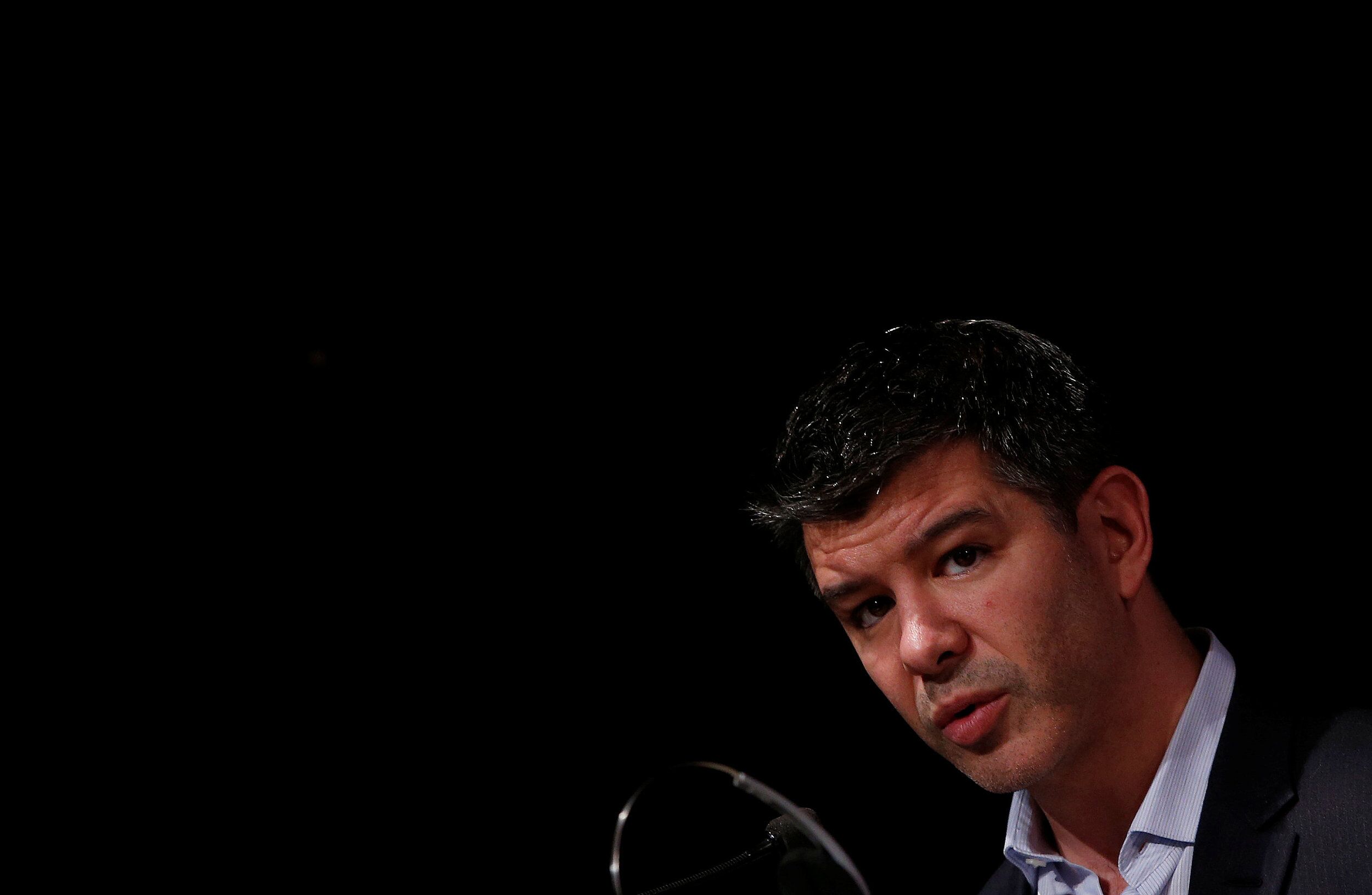

优步CEO特拉维斯•卡兰尼克,拍摄于2013年3月18日。Jeffery Salter — Redux Pictures

|

我知道,真正的选择是,要么“让特拉维斯成为特拉维斯”,要么竭力从受访对象口中撬出尽可能多的信息。我选择散步。 从严格意义上说,优步的故事并不完全等同于卡兰尼克的故事。这家打车服务初创公司,最初并不是他的主意。但毫无疑问的是,他是优步的中心人物。正是卡兰尼克提供的关键洞察力(即启用自由职业者,而不是聘用司机,购买汽车),将其他人“很有意思”的创业想法转化为一种无可争辩的突破性理念。自从优步首次流行开来,并开始向旧金山以外扩张以来,他一直担任CEO,强势推行铁腕政策,几乎无处不在。其结果是,卡兰尼克已经被等同于优步,就像比尔•盖茨之于微软,史蒂夫•乔布斯之于苹果,马克•扎克伯格之于Facebook。 卡兰尼克启动优步的时机几乎无可挑剔。这家公司完美地体现出信息技术行业下一波浪潮的特点。它绝对是一家“移动优先”的企业;要是没有iPhone,优步就不可能诞生。几乎从一开始,它就在全球范围内扩张——在套装软件和笨重的电脑仍然是常态的那个时代,这简直是不可想象的。此外,优步还是所谓的“零工经济”的领导者,巧妙地将自家技术与其他人的资产(他们的汽车)和劳动结合在一起,向他们支付独立承包商费用,而不是更加昂贵的员工福利。 现如今,优步的全职员工超过1.2万人,其中有大约一半常驻湾区。由于我们都拿起各自的夹克(在旧金山,哪怕是晴朗的7月份夜晚也有点干冷),我猜想散步意味着离开大楼。是的,我们会的。但卡兰尼克随即解释说,他想带我参观一下优步的办公室。就像其他亲力亲为的CEO一样,在卡兰尼克看来,优步的办公室不仅反映了该公司的价值观和愿景,同时还是他自身个性的延伸。 乔布斯亦是如此。在他去世前六个月,乔布斯坐在家中客厅的沙发上,向我骄傲地展示苹果新总部园区的一系列建筑图纸——可惜的是,他未能在有生之年目睹这栋大厦。几个月后,他亲自与一位树艺师商议,最终选择在新总部四周栽种杏树。 “这样说吧,你知道一座城市的建造历程是从什么时候开始的?” 卡兰尼克说。“到处都是干净的线条。这就像一座建造出来的城市。所以,这是‘干净的线条”。我们拥有五个品牌支柱:接地、平民主义、鼓舞人心、高度演变性,以及庄严感。这就是优步的个性。” 我们正站在他的办公桌旁,俯瞰优步办公室的神经中枢。通过安检后,一位访客会看到一排排毗邻的办公桌。当卡兰尼克重复这些品牌“支柱”(即接地、平民主义、鼓舞人心、高度演变性,以及庄严感)的时候,我频频点头,以示认可。但我并没有完全理解。对我来说,这些词汇有点晦涩,无论他多么热忱地解释其含义。 他所说的“接地”意指实用性。优步代表着终极意义上的实用性:它利用技术将人们从一个地方转移到另一个地方。但当这种概念出自一位市政工程师的儿子之口时,它就拥有了新的意义。卡兰尼克解释说,“接地就像音调。它是功能性直线。所有的会议室都以城市命名,按字母顺序排列,真的很实用。” 我此前听闻卡兰尼克愿意把无尽的时间投入到表面的细节上。然而,我还没有亲眼看到,他愿意潜心研究这家纷繁复杂的企业中似乎很神秘和飘渺的方面。 作为优步“庄严感”特质的一个例证,卡兰尼克指向会议上的天花板,并解释说它具有声学上的纯净效果。卡兰尼克对安静有着极致的要求:“我不喜欢声音,受不了很多噪音。”他自豪地宣称,一种名为K-13的建筑材料能够达到这种效果。“当这个楼层有800个人的时候,这种噪音消减措施可以让它平静下来。所以我可以轻柔地说话。”他把自己的声音降到一种几乎令人尴尬的轻柔低语。“你仍然可以听清楚。” 办公桌和内墙之间有一条走廊。卡兰尼克邀请我低头看看混凝土地板,那里蚀刻着一个由一系列相交线条构成的复杂图案。“这是旧金山的电网,”他说。“我称之为道路。”在整个工作日期间,他就是在这里来回踱步,经常一边走,一边打电话。“在白天,你会看到我在这里,我每周要走45英里。” 我们随后步入四楼游览。卡兰尼克引领我参观“纽约市”。正是在这间会议室,优步敲定了一笔高达12亿美元的筹资交易,该公司随后搬入市场街办公室。“这是第一笔让许多人为之疯狂的十亿级美元筹资交易。”他自豪地宣称。 我们乘电梯来到11楼。这是优步在这栋大楼占据的少数几个楼层之一。卡兰尼克特意创设了一种简朴的环境,用暴露的干墙和小于正常尺寸的办公桌等方式来模仿创业环境。 “至少99%的企业家不像马克•扎克伯格那样一帆风顺,你总得面临艰苦岁月。所以,我把这里称为洞穴,因为你正在经历困难时刻,你正处于黑暗中,而你真的在一个黑暗的地方。这是个隐喻。”他说。 五楼有几间以科幻小说命名的会议室。卡兰尼克对科幻经典著作如数家珍,就像一位美国内战爱好者能够飞快说出一连串重要战役一样。一间会议室以艾萨克•阿西莫夫的“基地”系列命名,另一间被命名为“火星救援”,第三间以“安得的游戏”命名。他声称科幻主题具有“高度演变性”——这个词意指未来。优步是一家痴迷于未来的公司。还有一个用来让人联想起意大利广场的中心区域。通往这片区域的走廊故意设计得令人困惑。在卡兰尼克的世界观中,迷失方向是好事。“这样一来,如果你是一位居民,你就知道这些走廊通向何处。”这是他设计的平民主义版本。“如果你是一位客人,你就会迷失方向。所以你可以判断谁是居民,谁是客人。” 终于,我们绕过卡兰尼克的办公桌进入他的秘密出口,顺着一段楼梯离开这栋大楼,走到优步办公室入口所在的街道。他告诉我,此行的计划是沿着横穿市中心的主干道市场街,走到旧金山湾堤岸。从那里,我们将前往游客众多的渔人码头,然后去金门大桥。尽管日落的余晖璀璨无比,但气温正在下降。 这是洛杉矶人卡兰尼克不能忍受的。“对于任何洛杉矶人来说,这都是最令人苦恼的。这就是为什么我有时候回到洛杉矶度周末,哪怕只是在海滩上感受一下阳光。” 卡兰尼克看上去满腹心事。一路上,他对各种事情发表即兴评论。比如,我说我最近很少听闻Square公司的消息——Twitter创始人杰克•多西领导的这家支付公司现在与优步同处一栋大楼。尽管优步是一家私营企业,而Square是一家上市公司,但Square变得非常低调。卡兰尼克若有所思地说道:“我们真的无福享受那种状态。” 我们开始谈论卡兰尼克的创业史,包括在2000年代初期绝望地为他的P2P文件共享初创公司Red Swoosh筹集资金。等到我们抵达旧金山湾堤岸的时候,黄昏已经降临。我想知道,在我们散步的时候,他是否会被认出来。不太可能,他说,只要我们在交谈,并且身处户外。 经过渔人码头,我们步入一家In‑N‑Out汉堡店,这家标志性的南加州快餐连锁店是卡兰尼克的最爱。我们开始谈论无人驾驶汽车,卡兰尼克暗示优步即将有大动作,但他还不能详谈。他透露说,这段六英里的路程早已成为他在夏天夜晚的例行事项,In‑N‑Out汉堡店当然是必经的一站。而且,卡兰尼克还有一位他没有说明身份的散步同伴。我后来得知,这位同伴是安东尼•莱万多夫斯基。此君曾在谷歌担任自动驾驶汽车工程师,后来创建了一家名为Otto的自动驾驶卡车公司。就在我与卡兰尼克一起走完这段路程仅仅几周之后,优步就斥资6.8亿美元收购了Otto。卡兰尼克告诉我,他利用与莱万多夫斯基一起散步的机会,吸收自动驾驶汽车的技术和商业计划愿景。 在讨论了卡兰尼克的创业时代之后,我想知道他如何看待优步已经成为一家更大、更成熟的公司这一事实。他的回答显示,他并不愿意以这种方式看待这家公司。他不再认识公司里的每一个人,但他仍然愿意与高级职位申请者进行长达数小时的面谈。卡兰尼克解释说,他喜欢在正式聘用某位员工之前,模拟与他或她一起工作的场景。 我问他是否喜欢运营一家大公司。“我的管理方式使得这家公司感觉并不大。”卡兰尼克再次回归他最喜欢的一个比喻:他把每个工作日视为一系列需要解决的问题。他显然认为自己不仅是首席执行官,而且是首席麻烦终结者。 庞大显然是可怕的。“我想说的是,你需要持续不断地让你的公司感觉很小。你需要创造机制和文化价值观,让你的企业感觉尽可能得小。这是你保持创新和快速发展的方式。但当企业处于不同规模的时候,你实现这种目标的方式是不同的。比如,当你超级小时,你只需要借助部落知识就能保持快速发展。但当企业超级大时,如果你只依靠部落知识,那就变得超级动荡,实际上你就会发展得很慢。所以你必须不断地找到秩序和混乱之间的平衡点。” 鉴于这家公司的员工队伍不再是一群生活中只有工作的单身年轻人,我想知道他如何管理优步稳健地走出纯粹的创业阶段?“我称之为红线,”他说。“当你驾驶一辆轿车的时候,你可以快速前行。但你有一条红线。每个人都有他们自己的红线。你想进入那个红线,看看引擎的潜力如何。你或许发现你能够榨取的引擎潜能或许超出你的想象。但你不能长时间超越那条红线。每个人都有自己的红线。” 他指出,已经有很多“优步宝宝”;相较于那些没有孩子,时间约束更少的员工,为人父母者往往更有效率。但卡兰尼克对员工工作/生活平衡的期望也有局限。“瞧瞧,如果有人的工作效率更高,他们的升职速度就更快。就是这样。这没什么可说的。” 在三个多小时的散步之后,夜晚已经变得寒冷,漆黑,而这场谈话也变得非常个人化。我们谈到优步如何从媒体宠儿进化为媒体恶棍。在这种形象大转变的过程中,卡兰尼克几乎愿意扮演同谋者的角色,经常亲自扮演恶棍,由此激起熊熊怒火。他说,这些行为是他的“傲慢瞬间,我会发表一些带有挑衅性的观点。” 我问他是否关心人们的想法。 “是的,”他承认自己多少有些遗憾。“无论是对于优步、我自己,还是我的交谈对象,这都不是好事。” 他的部分问题是,卡兰尼克似乎无法掩饰自己防御心态或者他的烦恼。他把自己的恼怒时刻归因于“激烈地寻求真相”。不顾他人感受,愿意说出内心真实想法的人,总会获得严苛的评价。就这一点而言,他并非个例。这是史蒂夫•乔布斯、杰夫•贝索斯,以及与卡兰尼克同时代的埃隆•马斯克共有的特征。卡兰尼克意识到这一点,他提到“创始人兼CEO必须是个混蛋才能成功这一互联网文化模因。”他抗拒这种观点,但他显然仅仅是不痴迷于此而已。 “我想这个问题的确是存在的。”他随即将话题从一般的模因转移到他自己身上。“‘他是个混蛋吗?’鉴于你跟我谈了这么长时间,你当然会被问到这个问题。‘他是个混蛋吗?’” 卡兰尼克毕竟是工程师出身,他想相信,这个问题有一个科学的答案。我说,这类问题的答案从来都取决于个人看法,与事实无关。他不这样认为。“我尝试着破解它是否属实,比如我是否让某些人激发起了一些与我没有做的事情有关的感受?我是个混蛋吗?我很想知道。” 他继续说道:“我不认为我是混蛋。我很确定我不是。” 但我想知道他是否在意别人的想法。“我想说的是,如果你是一位真相寻求者,你只是想要真相。如果你相信某件事不是真相,那么你就想继续追求真相。这就是我的思考范式。” 卡兰尼克不太可能听到他渴望的真相版本。在这趟散步之旅几周后,《纽约》杂志刊发了一篇专访布拉德利•图斯克的文章。图斯克是一位政治顾问,曾经在多场监管斗争中为优步提供咨询服务。谈到他自己愿意出于正确理由而接受“一些抨击”的时候,图斯克把自己比作卡兰尼克。“他知道,要做大事,你就会惹恼许多人。”随后,这篇文章的作者问图斯克,卡兰尼克是不是混蛋,并描述了他的反应。“他犹豫了一下。‘我们的谈话没有被录音吧?”我告诉他没有。“不,他不是混蛋。” 2017年早些时候,当一段记录卡兰尼克训斥优步司机的视频在网上疯传的时候,在许多人眼中,这个“混蛋”问题已经有了终极答案。卡兰尼克公开表示,这起事件显示他需要尽快“成长”。但发布这段声明时,他已经进入了人生的第五个十年。仅仅以年轻为借口,不再能解释他的行为。 走到这时候,卡兰尼克感受到了寒冷和疲惫。他提议继续走到金门大桥(这很可能意味着,我们还需要走半个小时),或者叫辆车返回优步办公室。我也感到寒冷和疲惫,但我请他选择。“我想我们还是叫辆车吧。”他说。 他拿出手机,叫了一辆优步专车。当我们在车内交谈时,这位优步司机只听了几分钟就意识到,他接到的这位“特拉维斯”——所有的优步司机都能看到付费乘客的名字——是优步CEO。 司机:你是特拉维斯吗? 卡兰尼克:是的。你怎么样,老兄? 司机:我从来没有见过你。 卡兰尼克:是的,是的。 司机:你好吗,老兄? 卡兰尼克:我很好,我很好。 司机:我不敢相信。 卡兰尼克:你怎么知道是我? 司机:我朝着后视镜看了一下。你看起来很眼熟。哎呀!我和CEO在一起。 卡兰尼克:很高兴见到你,伙计。 司机:谢谢,老兄。 卡兰尼克:你一直在开优步专车? 司机:一年,大约一年零二个月。 卡兰尼克:你以前是干嘛的? 司机:我是做兼职的,因为我住在旧金山,所以我需要更多的钱。 卡兰尼克:肯定的。 司机:然后我被解雇了,所以我现在全职工作。 这位司机解释说,他以前供职于AT&T,做了足足16年的技术支持工作,最近刚刚被解雇。卡兰尼克问他,现在能够掌握自己的工作时间,他是否“很激动”。司机说,他喜欢灵活性,但要是能挣更多的钱就更好了。卡兰尼克回应说,优步为司机提供了很多“多赚一笔”的途径。就在这时候,这位司机突然开始吐槽。他说,“嗯,你们的技术支持真的很糟糕。”卡兰尼克说,“是的,我正在解决这个问题,”并请求司机给他几个月时间来解决技术支持问题。 司机还抱怨说,他没有收到优步保证他有足够工作时间的电邮和短信——这是该公司为那些希望借助优步谋生的司机提供的一项奖励计划。然后,他告知CEO一些司机如何滥用优步的规则。比如,许多司机筛选叫车请求,以避免去不中意的目的地,比如远郊。 我们下车的时候,差不多已是深夜11点。卡兰尼克承诺说,他将跟进司机关切的问题。(在11点07分,他向我转发了一份内部回应,发信人是一位芝加哥的“高级社区运营经理”,他承诺说要调查相关问题。我后来问他,要是我没有同乘那部轿车,他是否会作出同样的反应。“你知道我每天从轿车里发出多少份用来回应司机反馈的电子邮件和短信?”他问道。“优步产品经理的反应通常都是,‘哦,老兄,我们马上处理。’”) 去年8月份,卡兰尼克发布的一则声明让许多优步观察家震惊不已。他承认,在中国这样一个他曾经宣称是该公司最重要的未来市场上,优步遭遇惨败:他已经将优步中国业务出售给了本土竞争对手滴滴出行。这或许是他职业生涯中最惨痛的失败。但即使在这里,完整的故事也更加微妙。优步每年在中国亏损10亿美元。通过将中国业务出售给滴滴出行,他的公司成为滴滴最大的股东,并将滴滴带到优步的董事会,卡兰尼克也一举实现了他最伟大的胜利之一。 突然间,他将一笔失败的20亿美元投资连本带利地转化为一家中国垄断企业价值60亿美元的股权。卡兰尼克也解决了该公司在中国市场看不到尽头的现金储备消耗,由此加固了优步的财务状况,为这家打车服务商在美国的IPO铺平了道路。 与此同时,优步显示它并没有失去对远大梦想的胃口。2016年10月下旬,其首席产品高管杰夫•霍尔顿发布了一本99页的白皮书,专门介绍优步对飞行车等黑科技的研究。他把这个项目称为“Uber Elevate”。该报告开篇写道:“想象一下从旧金山码头到圣荷西市中心上班,只需要15分钟。这趟行程通常需要差不多两个小时。”它继续解释优步对垂直起飞和着陆的汽车网络,以及构建它所需的基础设施的美好愿景。 要不是它详细谈论“市场可行性障碍”,还附有一个由17人组成的撰文和评论团队名单(其中包括来自美国宇航局、乔治亚理工大学和麻省理工学院的科学家),这本白皮书看上去似乎是一个精心制作的恶作剧。其中一位评论者名叫马克•摩尔。他曾经在美国宇航局供职30年之久,于2007年初加盟优步,出任航空工程总监。无论优步有什么缺点,可以肯定地说,它确实将天空视为极限。 尽管卡兰尼克宣称他信奉基于事实的实用性,但他最喜欢做的事情莫过于反复推敲新创意——越古怪越好。2016年夏天,我与卡兰尼克和几位优步高管一起搭乘私人飞机从北京飞往杭州。这座位于上海附近的沿海城市是阿里巴巴集团的总部所在地,它也由此成为中国互联网世界的重要枢纽。 在起飞之前,卡兰尼克大声地询问他的首席交易人兼筹款人埃米尔•迈克尔,优步能否在没有投资银行家参与的情况下公开上市。律师出身的迈克尔建议采取反向并购。这是一种多少有点可疑的资本运作技术,具体方式是:一家私人公司通过收购一家劣质上市公司来登陆股市。卡兰尼克建议不要使用银行家,而是将所筹资本的3%(这笔费用原本会授予银行家)捐赠给慈善事业。当我建议把这笔钱赠送给司机时,卡兰尼克面露喜色。他说他想给司机提供股权,但优步发现相关的证劵法规相当复杂。 这架私人手机起飞后,卡兰尼克陷入沉思。他告诉我,他长期以来一直梦想成为一名调查记者,而且读过一本关于柬埔寨红色高棉的报道选集。他说,这份“梦想的工作”能够激发起他的正义感。他甚至有一个调查项目创意:他和我去孟买呆上六个月,住在贫民窟,并撰写这段经历。“我打算像原住民那样,把头发留长,穿不同的衣服。”他说。 我逐渐意识到,这在一定程度上是卡兰尼克自娱自乐的方式,但也反映了他真挚的一面。他很可能被红色高棉蹂躏的柬埔寨人民,或者孟买贫民窟居民的不幸遭遇所触动,但他还没有为旧金山市的无家可归者做任何善事。他的想法令人兴奋,但也令人费解。他喜欢展开奔放的想象。 与卡兰尼克的最后一次谈话中,我主动提到亚历山大•汉密尔顿,部分是为了验证我的记忆:早在林-曼努尔•米兰达创作并参演的百老汇音乐剧《汉密尔顿》大获成功之前,卡兰尼克就对这位美国首任财政部长很感兴趣。为什么当卡兰尼克第一次读到罗恩•彻诺撰写的传记时,他就如此钦佩汉密尔顿?我问道。 “他身上有许多令人赞叹的品质,”他说。“在他那个时代,汉密尔顿是一位企业家。但是,他创建的并不是一家公司,而是一个国家。他身处舞台中央。要是他不在那里,美国将演变为一个非常不同的国家。他既是哲学家,也是执行者。他有很多伟大的品质。他洞悉未来的方式让我很受启发。就很多方面而言,美国实践了他构想的未来。我认为,正是拜他的愿景所赐,我们成为了一个如此杰出的国家。” 汉密尔顿不知道何时保持安静,而且树敌无数。我想知道,卡兰尼克是否认识到了汉密尔顿遭遇的无数辱骂?“嗯,你知道的,这个家伙面临过很多逆境。优步也一样。我们喜欢说,‘知道什么是正确的,为之而战,不要做傻瓜。’他只做他认为正确的事情。当你这样做的时候,当你做真正不一样的事情时,你就会有一些反对者。你只需要习惯就好。” 在许多人看来,特拉维斯•卡兰尼克就是一位傻瓜,但他当然不这样认为。这位优步CEO很有可能永远都不会习惯反对者的抨击。逆境,毕竟已经成为旅程的一部分。(财富中文网) 译者:Kevin |

Understanding my true choice to be between “letting Travis be Travis” on the one hand and trying to pry information out of a penned‑in subject on the other, I opt for the walk. Uber’s story isn’t strictly synonymous with Kalanick’s—the ride-hailing startup wasn’t initially his idea—but he is indisputably its central character. Kalanick supplied the critical insight that transformed someone else’s startup idea from merely interesting to undeniably groundbreaking, by hitting on the idea of enabling freelancers rather than hiring drivers and buying cars. And he has been Uber’s iron-fisted, omnipresent chief executive from the time it first gained traction and began expanding beyond San Francisco. As a result, Uber has become as identified with Kalanick as Microsoft, Apple, and Facebook are with Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg, respectively. Kalanick’s timing with Uber was impeccable. The company perfectly exemplifies the attributes of the information-technology industry’s next wave. It is emphatically a mobile-first business; if there had been no iPhone, there would have been no Uber. And it expanded globally almost from its beginning, far earlier than would have been possible in an era when packaged software and clunky computers were the norm. Uber is also a leader of the so‑called gig economy, cleverly marrying its technology with other people’s assets (their cars) as well as their labor, paying them independent-contractor fees but not costlier employee benefits. Today Uber employs more than 12,000 people full-time, about half in the Bay Area. Because we’ve grabbed our jackets—even clear July nights in San Francisco can be brisk—I assume a walk means we’ll leave the building. And we will. But first Kalanick explains that he wants to give me a tour of Uber’s offices. Like other hands‑on CEOs before him, Kalanick views his company’s offices not only as a reflection of the company’s values and aspirations, but also an extension of his own personality. Jobs was the same way. Six months before his death he sat down next to me on a couch in his Palo Alto living room and proudly showed me a bound book of architectural drawings for the new Apple corporate campus he wouldn’t live to see. Months later he personally worked with an arborist to pick the apricot trees for the project. “You know when, like, a city is made from scratch?” says Kalanick. “You’ve got clean lines everywhere. This is like a manufactured city. So this is ‘clean lines.’ We have five brand pillars: grounded, populist, inspiring, highly evolved, and elevated. That’s the personality of Uber.” We’re standing near his desk, looking out over the nerve center of Uber’s offices, the row after row of adjoining desks a visitor sees after first passing through security. As Kalanick repeats these brand “pillars”—grounded, populist, inspiring, highly evolved, and elevated—I nod my head in acknowledgment. But I never completely understand what they are really about. It’s all a bit squishy to me, no matter how earnestly he explains them. By “grounded” he generally means practical. Uber is the ultimate in practicality: It uses technology to move people from one place to another. Yet the concept takes on new meaning in the words spoken by the son of a public-works engineer. “Grounded is like tonality,” says Kalanick. “It’s functional straight lines, the whole thing. All of the conference rooms are named for cities. They’re in alphabetical order. It’s just very practical.” I had read of Kalanick’s willingness to devote untold hours to superficial minutiae. Yet I hadn’t personally witnessed his willingness to dive into seemingly arcane and ethereal aspects of such a demanding business. As an example of Uber’s “elevated” nature, Kalanick points to the acoustically pure ceilings in a conference room. A quiet freak— “I don’t like sound. I don’t do well with lots of noise”—he proudly identifies the building material, K‑13, that pulls off the effect. “When you have 800 people on this floor, the acoustic treatment makes it calm. So I can talk softly,” he says, lowering his voice to an almost awkwardly gentle murmur, “and you can hear me.” Nearby is a corridor between the desks and an interior wall. Kalanick invites me to look down at the concrete floor, where an intricate pattern is etched with a series of intersecting lines. “Right here is the San Francisco grid,” he says. “I call it the path.” It is here that he paces back and forth throughout the workday, often on his cell phone. “In the daytime you’ll see me here,” he says. “I’ll do 45 miles a week.” The tour proceeds around the fourth floor. Kalanick shows me “New York City,” the conference room where Uber negotiated the deal in which it raised $1.2 billion, just before the company moved into the Market Street offices. “The first billion-dollar deal that blew people’s minds,” he says proudly. We take an elevator to the 11th floor—one of a handful Uber has in the building—where Kalanick has created an austere setting, a place to mimic the entrepreneurial environment, with exposed drywall and smaller-than-usual desks. “When you’re an entrepreneur—at least the 99% of entrepreneurs that are not Mark Zuckerberg—you have hard times,” he says. “So this right here is what I call the cave, because when you’re going through hard times you’re in the dark, you’re literally in some dark place. It’s a metaphor.” Down on the fifth floor are areas with conference rooms named after science-fiction books. Kalanick knows the sci‑fi canon the way a Civil War buff can rattle off important battles. One section is named for Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, another for The Martian, a third for Ender’s Game. He brands the sci‑fi theme “highly evolved,” by which he means the future. Uber is a company obsessed with the future. Elsewhere there’s a central area meant to evoke an Italian piazza. The hallways leading to it are confusing, by design. In Kalanick’s worldview, disorientation is good. “So if you are a resident you know where everything is,” he says. This is his version of populism. “If you are a guest, you’re lost. So you can tell who’s a resident and who’s a guest.” II. We finally leave the building by slipping past Kalanick’s desk to his secret exit and a staircase that leads directly out onto a street around the corner from the entrance to Uber’s office. The plan, he tells me, is to walk down Market Street, the main thoroughfare that cuts through the center of downtown San Francisco, to the Embarcadero along the waterfront. From there we’ll head to the touristy Fisherman’s Wharf area and then toward the Golden Gate Bridge. Despite the brilliant sunset, the temperature is falling. Kalanick, forever an Angeleno, can’t bear it. “This is the most upsetting thing for somebody from Los Angeles,” he says. “That’s why I sometimes do weekends in L.A. Just to be at the beach.” Kalanick is in a reflective mood, and as we walk he riffs on all manner of things. I remark, for example, on how little I’ve heard of late about Square, the payments company headed by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey, whose offices, for now, are in the same building as Uber. Although Uber is private and Square (sq, +1.17%) is publicly traded, Square has become decidedly low profile. Muses Kalanick: “We don’t really have that luxury.” We begin talking about Kalanick’s entrepreneurial history, including his desperate hunt for funding in the early 2000s at his peer-to-peer file-sharing startup, Red Swoosh. By the time we hit the Embarcadero, the curvilinear street that runs along the waterfront between the Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge, dusk has set in. I wonder aloud if he’ll be recognized during our walk. Not likely, he says, so long as we’re in conversation and outdoors. Out past Fisherman’s Wharf, we step into an In‑N‑Out Burger, the iconic SoCal fast-food chain and a Kalanick favorite. By now we’re discussing driverless cars and Kalanick suggests big moves are ahead that he can’t yet discuss. He lets on that this six-mile walk, always including the stop at In‑N‑Out Burger, has become a summer-evening routine and that he typically walks it with one person he won’t identify. I later learn his walking partner is Anthony Levandowski, the ex–Google autonomous vehicles engineer who went on to found Otto, a self-driving truck company. Uber will purchase Otto for $680 million just a few weeks after our walk, and Kalanick tells me he used his time with Levandowski to absorb the technology and business plan vision for autonomous vehicles. (Uber and Alphabet are now embroiled in a lawsuit. See our article on “What Could Take Down Uber?”) Having discussed Kalanick’s entrepreneurial days, I want to know how he views the bigger, more established company Uber has become. His answers betray a reluctance to think of the company that way. He doesn’t know everyone at the company anymore, but he still conducts hours-long interviews with top prospects. Kalanick explains that he likes to simulate what it would be like to work with someone before hiring them. I ask if he likes running a big company. “The way I do it, it doesn’t feel big,” he says, falling back on a favorite trope: that he approaches his day as a series of problems to be solved. He obviously thinks of himself as troubleshooter-in-chief as much as a CEO. Bigness clearly is scary. “I would say you constantly want to make your company feel small,” he says. “You need to create mechanisms and cultural values so that you feel as small as possible. That’s how you stay innovative and fast. But how you do that at different sizes is different. Like when you’re super small, you go fast by just tribal knowledge. But if you did tribal knowledge when you’re super big it would be chaotic and you’d actually go really slow. So you have to constantly find that line between order and chaos.” How, I wonder, does he plan to manage the transition out of the pure startup stage, now that the company is no longer composed of a bunch of young, single people with nothing in their lives but work? “I call it the red line,” he says. “In a car, you can go fast. But you have a red line. And everybody has their own personal red lines. You want to push into that red line and see what that engine’s made of. You might find you’ve got more under the hood than you thought. But you can’t sit over the red line for too long. And everybody’s got their own personal red line.” He points out that already there are many “Uber babies” and that parents tend to be more efficient than childless people with fewer constraints on their time. There are limits, though, to Kalanick’s aspirations for work/life balance for his employees. “Look, if somebody’s producing more, they’re going to rise faster. That just is. There’s no way around that.” III. After more than three hours of walking, the night has turned cold and dark—and the conversation turns deeply personal. We discuss the narrative arc of how Uber has progressed from media darling to media villain. Kalanick was an almost willing accomplice in this metamorphosis, often managing to stoke the fire by playing the villain himself. He refers to these actions as his “little moments of arrogance where I say something provocative.” I ask if he cares what people think. “Yeah,” he says, acknowledging some regrets. “It’s not good for Uber. It’s not good for me. It’s not good for the people that I’m talking to. It’s bad for everybody.” Part of his problem is that Kalanick seemingly isn’t able to hide his defensiveness or his annoyance. He ascribes his moments of pique to “fierce truth seeking.” Someone willing to say exactly what he thinks, empathy be damned, will be judged harshly. He’s not alone. It’s a trait that has been repeatedly ascribed to Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos, as well as to Kalanick’s contemporary, Elon Musk. Kalanick is aware of this, referring to the “meme that founder-CEOs have to be assholes to be successful.” He rejects that notion, but he’s obviously just short of obsessed by it. “I think there’s this question out there,” he says, shifting away from general memes to himself. “‘Is he an asshole?’ Since you’ve spent time with me, one of the big questions you’re going to get is, ‘Is he an asshole?’” Engineer that he is, Kalanick wants to believe there is a scientific answer to the question. I suggest the answer is and always will be in the realm of opinion, not fact. He rejects this. “Understanding whether it’s real or not, like do I trigger something in certain people that’s related to something that I didn’t do? Or am I an asshole? I’d love to know.” He continues: “I don’t think I’m an asshole. I’m pretty sure I’m not.” But I want to know if he cares one way or the other what people think. “What you’re hearing me say is that if you are a truth seeker, you just want the truth. And if you believe that something is not the truth, then you want to keep seeking for truth. That’s just how I’m wired.” Kalanick is unlikely to ever hear the version of the truth he craves. Weeks after our walk, New York magazine publishes an interview with Bradley Tusk, the political consultant who has worked for Uber on multiple regulatory fights. In discussing his own willingness to take “a few hits” for the right reasons, Tusk compares himself to Kalanick. “He understands to achieve really big things, you’re going to piss a lot of people off,” Tusk says. Then the writer asks Tusk if Kalanick is an asshole and describes his reaction: “He hesitates. ‘Are we off the record?’ I tell him we are not. ‘No, he is not an asshole.’” The “asshole” question was answered for good in the eyes of many early in 2017 when a video of Kalanick berating a driver went viral. Kalanick suggested publicly the incident showed his need to “grow up.” But he made this statement having recently entered his fifth decade. Youthfulness alone can no longer explain his behavior. Kalanick, who at this point in our walk is cold and tired, offers to continue to the Golden Gate Bridge, likely another half-hour down the trail, or to call a car and head back to the Uber offices. I’m tired and cold too, but I ask him to choose. “I think we’re getting a car,” he says. He pulls out his smartphone and summons an Uber. It takes the driver just a few minutes of listening to our discussion to realize that the “Travis” he has picked up—all Uber drivers have the first name of their paying passenger—is the company’s CEO. DRIVER: Are you Travis? KALANICK: Yeah. How you doing, man? DRIVER: I never met you. KALANICK: Yeah, yeah. DRIVER: How you doing, man? KALANICK: I’m good. I’m good. DRIVER: I can’t believe it. KALANICK: How’d you connect the dots? DRIVER: I was looking in the rearview mirror a little bit. And you looked so familiar. Damn, I’m with the CEO. KALANICK: It’s good to meet you, man. DRIVER: Thanks, man. KALANICK: How long you been doing the Uber thing? DRIVER: A year, about a year and two months. KALANICK: What were you doing before? DRIVER: I was doing it part-time because I live in San Francisco, so I need more money. KALANICK: For sure. DRIVER: And then I got laid off, so I’m doing it full-time now. The driver explains that he’d recently been laid off after 16 years at AT&T (t, +0.87%), where he worked in tech support. Kalanick asks if he is “pumped” about being able to control his time now as an Uber driver, and the driver says he likes the flexibility, though the money could be better. When Kalanick says that Uber has lots of ways for drivers “to make an extra buck,” the tide turns. “Well, your tech support really sucks,” the driver says. “That’s true, I’m working on it,” says Kalanick, asking for a few months to fix what’s broken. The driver also complains that he’s not getting emails and text messages informing him of guaranteed hours, an incentive program that is a staple for drivers trying to make a living on Uber. He then gives the CEO a lesson on how drivers abuse Uber’s rules. For example, many drivers screen rides to avoid undesirable destinations, like far-out suburbs. By the time we get out of the car, at the same side entrance where we exited the Uber building hours earlier, it’s nearly 11 p.m. Kalanick promises to follow up with the driver’s concerns. (At 11:07 p.m. he forwards me an internal response from a “senior community operations manager” in Chicago promising to look into them. I ask later if he would have been as responsive if I hadn’t been in the car. “You know how many emails and texts I send from cars, from drivers giving me feedback?” he asks. “Uber product managers are like, ‘Oh man, here we go.’”) IV. Last August, Kalanick stunned many Uber watchers by admitting defeat in what he had touted as the company’s most important future market: He sold Uber China to Chinese rival Didi. It was perhaps the most painful failure of his career. But even here the full story is more nuanced. Uber was losing a billion dollars a year in China. And by selling to Didi—which made his company Didi’s largest shareholder and brought Didi onto Uber’s board—Kalanick in one fell swoop also achieved one of his greatest triumphs. All of a sudden he had parlayed a failing $2 billion investment into a stake worth $6 billion in a rising Chinese monopoly. And by eliminating a no‑end‑in‑sight drain on the company’s cash reserves, he shored up Uber’s finances, paving the way for an eventual initial public offering of Uber’s shares in the United States. Meanwhile, Uber showed it hadn’t lost the appetite to dream big. In late October 2016 its top product executive, Jeff Holden, published a 99-page white paper devoted to Uber’s research into flying cars, of all things. He dubbed the project “Uber Elevate.” The report begins: “Imagine traveling from San Francisco’s Marina to work in downtown San Jose—a drive that would normally occupy the better part of two hours—in only 15 minutes.” It goes on to explain Uber’s vision for a network of cars that take off and land vertically and the infrastructure it would take to build it. The paper might have seemed like an elaborate prank but for its detailed discussion of “market feasibility barriers” and its 17-person contributor-and-reviewer roster, including scientists from NASA, Georgia Tech, and MIT. One of those reviewers, a 30-year NASA veteran named Mark Moore, joined Uber full time in early 2017 as director of aviation engineering. Whatever Uber’s shortcomings, it’s safe to say it literally considers the sky to be the limit. For all his professed just-the-facts practicality, Kalanick loves nothing more than to bat around ideas, the zanier the better. In the summer of 2016, I traveled by private jet with Kalanick and several top Uber executives from Beijing, the Chinese capital, to Hangzhou, the coastal city near Shanghai that is home to Alibaba and thus an important hub of the Chinese Internet business. Before takeoff, Kalanick wonders aloud to Emil Michael, his top dealmaker and fundraiser, if Uber could go public without investment bankers. Michael, a lawyer by training, suggests instead a reverse merger, a somewhat dubious technique whereby a private company buys an inferior public company for its listing. Kalanick suggests using no bankers but giving 3% of the capital raised—the fee bankers would have received—to charity. When I suggest giving that money instead to drivers, Kalanick lights up. He says he wants to give equity to drivers, something upstart Juno has begun doing, but Uber has found the securities-law implications to be complicated. Once airborne, Kalanick turns positively pensive. He tells me he has long dreamed of being an investigative journalist, having once read an anthology of reporting about the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. The “dream job,” he says, appeals to his sense of justice. He even has an idea for an investigative project: He and I need to go to Mumbai for six months, he says, and live in the slums and write about the experience. “I’m going to grow out my hair and wear different clothes and go native,” he says. I learn over time that this is partly how Kalanick amuses himself and partly a reflection of his earnest side. He may well be moved by the plight of the Cambodian people under the murderous Khmer Rouge or by the slum dwellers of Mumbai, yet he hasn’t done anything about the homeless in his own city of San Francisco. His ideas are thrilling but also baffling. And he relishes challenges to his flights of fancy. In one of my last conversations with Kalanick, I bring up the topic of Alexander Hamilton, in part to verify my recollection that Kalanick had been interested in the first U.S. Treasury Secretary long before Lin-Manuel Miranda’s epically successful musical exploded on Broadway. Why, I ask, did Kalanick admire Hamilton so much when he first read Ron Chernow’s biography? “There’s much to admire about him,” he says. “He was an entrepreneur in his own time. But instead of creating a company he was creating a country. He was right at the center. The U.S. would be a very different place if he wasn’t there. He was a philosopher, but he was also an execution guy. He had a lot of great qualities. I think just so much about how he saw the future. And in many ways America lived that out, and I think we became a prominent country because of his vision.” Hamilton didn’t know when to keep quiet, and his list of enemies was long. Did Kalanick identify, I wonder, with the extraordinary amount of public abuse Hamilton withstood? “Well, look,” he says, “this guy had a lot of adversity. We have this thing at Uber. We like to say, ‘Know what’s right, fight for it, don’t be a jerk.’ He just did what he thought was right. And when you do that, when you’re doing something really, really different, you’re going to have some naysayers. You just have to get used to that.” Travis Kalanick, a jerk to many but not to himself, very likely will never get used to the naysayers. Adversity, after all, has become part of the journey. |