美国在2023年5月11日结束新冠疫情公共卫生紧急状态。5月5日,世界卫生组织(World Health Organization)宣布新冠疫情不再构成“国际关注的公共卫生紧急事件”(简称PHEIC)。世卫组织从2020年1月30日起将新冠疫情定性为国际关注的公共卫生紧急事件。

但无论世卫组织还是白宫都明确表示,虽然疫情紧急状态已经结束,但病毒并没有消失,可能继续造成严重破坏。

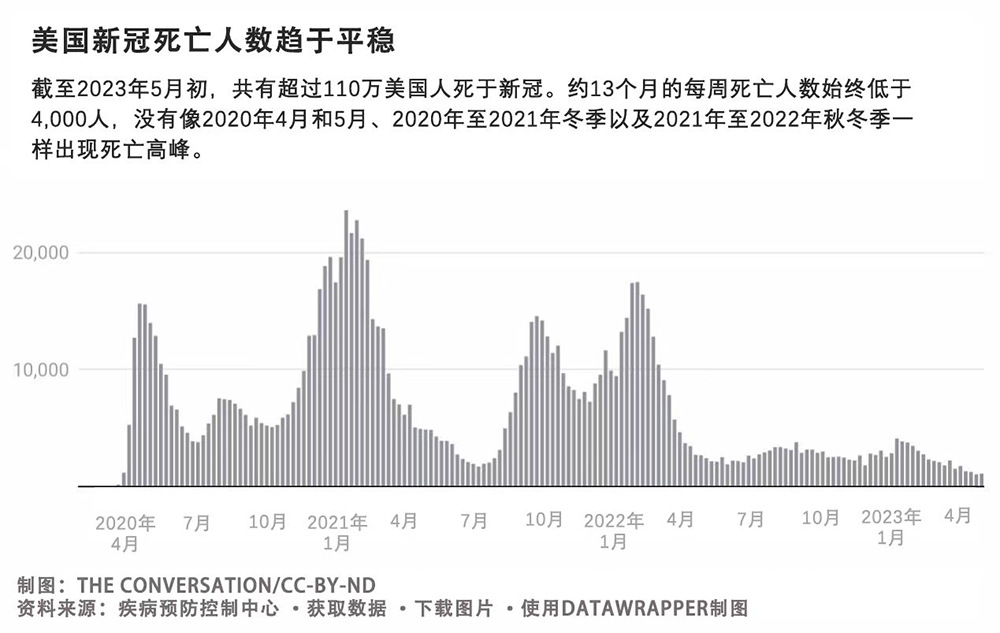

世卫组织总干事谭德塞指出,根据报告病例统计,新冠病毒在美国造成超过100万人死亡,在全球造成约700万人死亡,但他表示全球实际死亡人数可能接近2,000万人。他表示,虽然新冠疫情全球紧急状态已经结束,但依旧是一个“既定且持续的健康问题”。

The Conversation采访了公共卫生专家玛丽安·莫泽·琼斯和埃米·劳伦·费尔柴尔德,分析这些变化的大背景,并解释了它们对下一阶段疫情的影响。

1. 结束全国疫情紧急状态意味着什么?

美国结束联邦紧急状态,表明从科学和政治上判断,新冠疫情的急性期已经结束,联邦政府不需要再专门拿出资源,防止新冠跨境传播。

实际上,这意味着2020年1月31日首次宣布的联邦公共卫生紧急状态以及2020年3月13日由前总统唐纳德·特朗普宣布的新冠疫情全国紧急状态,都将结束。

联邦政府宣布紧急状态,可以减少无数繁文缛节,更高效地应对疫情。例如,宣布紧急状态使联邦政府可以拨款,以支持联邦政府部门向州和地方政府提供必要的人员、设备、物资供应和服务。此外,宣布紧急状态可提供资金和其他资源,对新冠疫情的起因、治疗或预防启动调查,并与其他部门签订合同以满足紧急状态下的需求。

紧急状态使联邦政府可以暂停提供许多医疗保险、医疗补助和儿童健康计划(Children’s Health Program,简称CHIP),提供更广泛的医疗保健服务,用于应对疫情。而且,人们可以免费获得新冠检测、治疗和疫苗,医疗补助和医疗保险也更容易覆盖远程医疗服务。

最后,特朗普政府利用国家紧急状态动用了《公共卫生服务法案》(Public Health Service)第42条。根据该条规定,为防止传染病传播,联邦政府有权停止办理入境。在正常情况下,避难者以及正常办理手续入境美国的其他人,在这条规则下均被拒绝入境。

2. 美国国内政策将发生哪些调整?

据美国联邦政府估计,有1,500万人可能失去医疗补助或CHIP保险。另外一项分析预测,高达2,400万人将失去医疗补助。

在疫情之前,各州要求人们每年证明其符合医疗补助的收入条件和其他资格要求。这会导致“重复申请”,在这个过程中,没有完成续期文书工作的被保险人,将被定期清理出州医疗补助计划,之后需要重新申请和证明自己的资格。

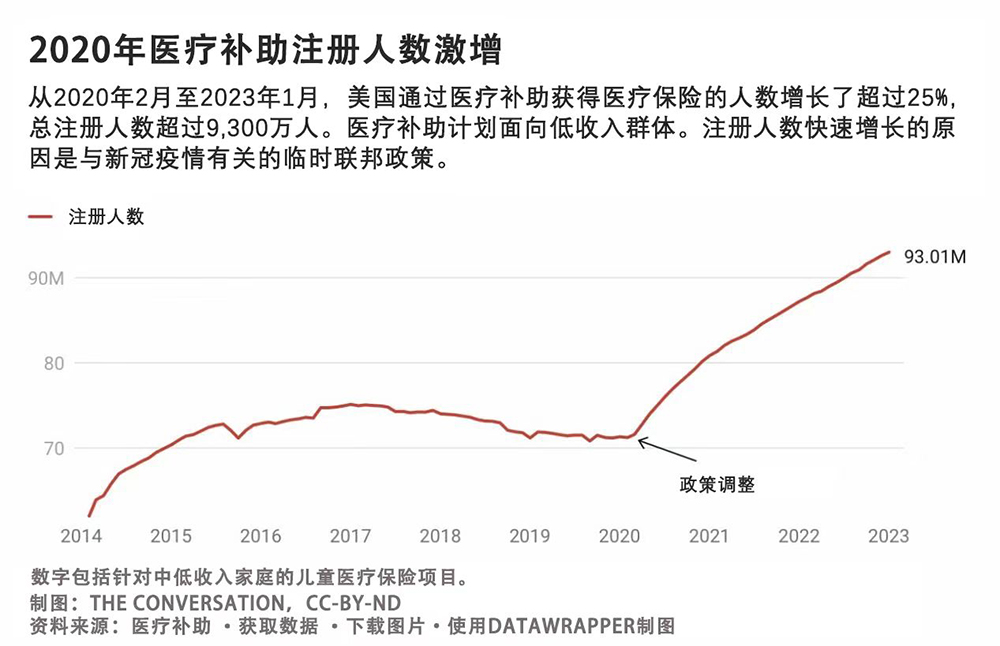

2020年3月,美国国会颁布了医疗补助的连续注册规定,禁止各州在疫情期间取消任何人享受医疗补助的资格。从2020年2月至2023年3月31日,医疗补助和CHIP的注册人数增长约23.5%,总计达到9,300万人。在2022年12月的拨款法案中,美国国会批准在2023年3月31日终止连续注册的规定。

拜登政府称,这段时间足以保证患者不会“突然失去享受医疗补助的机会”,而且各州的医疗补助预算从2020年开始可获得应急资金,不会“出现断崖式下跌”。

但在此期间注册医疗补助或为子女注册CHIP的许多人,却直到他们要在几个月后真正失去了这些福利,才意识到这些变化。

4月,至少有五个州已经开始清理医疗补助参与者。其他州则发出了终止通知和续期通知,将从5月、6月和7月开始清理医疗补助的参与者。

只有俄勒冈州启动了综合计划,以最大程度减少被清理人数。俄勒冈州正在执行为期五年的联邦示范项目,通过这个项目,该州可允许收入达到联邦贫困线以上200%的居民继续享受医疗补助,并允许符合条件的儿童享受医疗补助至6岁。许多州正在尝试更多更限制性策略,以完善续期程序,减少重复申请。

在疫情期间被纳入医疗保险范围的远程医疗服务,将继续作为保险项目,直至2024年12月。医疗保险还将行为和精神远程医疗服务作为一项永久性福利。

结束紧急状态还意味着联邦政府将不再承担新冠疫苗和治疗费用。但4月,拜登政府公布了一项规模达到110亿美元的公私合作“补助连接通道项目”,通过各州和地方卫生部门和药店为无保险人群免费提供新冠疫苗和治疗。有保险的人群根据保险类型,可能会产生自付费用。

结束紧急状况取消了对出入境的疫情防控限制。大批移民聚集在美墨边境,预计将在未来几周入境美国,这将令已经不堪重负的医护人员和设施更加紧张。

3. 结束紧急状态对于疫情的状态意味着什么?

政府宣布进入大流行状态意味着经过评估后,确认一种疾病,无论是已知疾病还是新型疾病,都具有“特别强大的”向人传播的能力,对美国两个或更多州构成公共卫生风险,而且需要国际合作控制其传播。但宣布紧急状态结束并不意味着一切恢复正常。

2023年5月3日发布的最新版全球新冠疫情长期疾病管理指南呼吁各国“保持足够的能力、作战准备和灵活性,在新冠疫情爆发期间能够大规模响应,同时维持其他必要医疗服务,为应对更严重或更强大的新病毒变种做好准备。”

前白宫新冠疫情响应协调官德博拉·伯克斯最近警告,奥密克戎变异株仍在继续变异,可能对目前的治疗药物产生抗体。她呼吁联邦政府资助更多对治疗药物和效果更持久的疫苗的研究,提供对许多变异株的保护力。

在伯克斯发出警告的同时,有多个州已经不再召开新冠疫情新闻发布,并关闭了接触风险通知系统,联邦政府也停止了免费居家新冠检测项目。

随着紧急状态结束,美国疾病预防控制中心(CDC)也将公布新冠数据的方式,转变为“持续全国新冠监控”模式。随着紧急状态结束,新冠监控和宣传策略的调整意味着病毒不再是媒体关注的对象,尽管它并没有从我们的生活和社区中消失。

4. 各州和地方的疫情防控措施会受到哪些影响?

联邦政府宣布结束紧急状态,并不影响各州或地方层面宣布紧急状态。各州宣布进入紧急状态,可以分配资源满足疫情防控的需求,其中包括相关规定,一旦新冠病例增多可以做出响应,由其他州的医生和其他医疗提供商现场或通过远程医疗接诊。

但美国大多数州都结束了当地的公共卫生紧急状态。特拉华州、伊利诺伊州、马萨诸塞州、纽约州、罗德岛和得克萨斯州宣布的紧急状态在2023年5月3日依旧有效,将到5月底终止。到目前为止,只有马萨诸塞州州长莫拉·希利表示,将“延长公共卫生紧急状态所带来的”与医疗人员和紧急医疗服务有关的“重要的灵活性”。

有些州可能选择将新冠疫情时期的应急标准作为长期措施,例如放宽对远程医疗和州外医疗提供商的限制等,但我们认为无论是政客还是公众,需要很长时间才能重新接受与新冠直接相关的任何紧急命令。(财富中文网)

本文为2023年2月3日发表的原文的更新版本。

玛丽安·莫泽·琼斯现任俄亥俄州立大学(The Ohio State University)医疗服务管理、政策与历史副教授,埃米·劳伦·费尔柴尔德现任俄亥俄州立大学公共卫生系主任兼教授。

本文依据知识共享许可协议转载自The Conversation。阅读原文。

翻译:刘进龙

审校:汪皓

美国在2023年5月11日结束新冠疫情公共卫生紧急状态。5月5日,世界卫生组织(World Health Organization)宣布新冠疫情不再构成“国际关注的公共卫生紧急事件”(简称PHEIC)。世卫组织从2020年1月30日起将新冠疫情定性为国际关注的公共卫生紧急事件。

但无论世卫组织还是白宫都明确表示,虽然疫情紧急状态已经结束,但病毒并没有消失,可能继续造成严重破坏。

世卫组织总干事谭德塞指出,根据报告病例统计,新冠病毒在美国造成超过100万人死亡,在全球造成约700万人死亡,但他表示全球实际死亡人数可能接近2,000万人。他表示,虽然新冠疫情全球紧急状态已经结束,但依旧是一个“既定且持续的健康问题”。

The Conversation采访了公共卫生专家玛丽安·莫泽·琼斯和埃米·劳伦·费尔柴尔德,分析这些变化的大背景,并解释了它们对下一阶段疫情的影响。

1. 结束全国疫情紧急状态意味着什么?

美国结束联邦紧急状态,表明从科学和政治上判断,新冠疫情的急性期已经结束,联邦政府不需要再专门拿出资源,防止新冠跨境传播。

实际上,这意味着2020年1月31日首次宣布的联邦公共卫生紧急状态以及2020年3月13日由前总统唐纳德·特朗普宣布的新冠疫情全国紧急状态,都将结束。

联邦政府宣布紧急状态,可以减少无数繁文缛节,更高效地应对疫情。例如,宣布紧急状态使联邦政府可以拨款,以支持联邦政府部门向州和地方政府提供必要的人员、设备、物资供应和服务。此外,宣布紧急状态可提供资金和其他资源,对新冠疫情的起因、治疗或预防启动调查,并与其他部门签订合同以满足紧急状态下的需求。

紧急状态使联邦政府可以暂停提供许多医疗保险、医疗补助和儿童健康计划(Children’s Health Program,简称CHIP),提供更广泛的医疗保健服务,用于应对疫情。而且,人们可以免费获得新冠检测、治疗和疫苗,医疗补助和医疗保险也更容易覆盖远程医疗服务。

最后,特朗普政府利用国家紧急状态动用了《公共卫生服务法案》(Public Health Service)第42条。根据该条规定,为防止传染病传播,联邦政府有权停止办理入境。在正常情况下,避难者以及正常办理手续入境美国的其他人,在这条规则下均被拒绝入境。

2. 美国国内政策将发生哪些调整?

据美国联邦政府估计,有1,500万人可能失去医疗补助或CHIP保险。另外一项分析预测,高达2,400万人将失去医疗补助。

在疫情之前,各州要求人们每年证明其符合医疗补助的收入条件和其他资格要求。这会导致“重复申请”,在这个过程中,没有完成续期文书工作的被保险人,将被定期清理出州医疗补助计划,之后需要重新申请和证明自己的资格。

2020年3月,美国国会颁布了医疗补助的连续注册规定,禁止各州在疫情期间取消任何人享受医疗补助的资格。从2020年2月至2023年3月31日,医疗补助和CHIP的注册人数增长约23.5%,总计达到9,300万人。在2022年12月的拨款法案中,美国国会批准在2023年3月31日终止连续注册的规定。

拜登政府称,这段时间足以保证患者不会“突然失去享受医疗补助的机会”,而且各州的医疗补助预算从2020年开始可获得应急资金,不会“出现断崖式下跌”。

但在此期间注册医疗补助或为子女注册CHIP的许多人,却直到他们要在几个月后真正失去了这些福利,才意识到这些变化。

4月,至少有五个州已经开始清理医疗补助参与者。其他州则发出了终止通知和续期通知,将从5月、6月和7月开始清理医疗补助的参与者。

只有俄勒冈州启动了综合计划,以最大程度减少被清理人数。俄勒冈州正在执行为期五年的联邦示范项目,通过这个项目,该州可允许收入达到联邦贫困线以上200%的居民继续享受医疗补助,并允许符合条件的儿童享受医疗补助至6岁。许多州正在尝试更多更限制性策略,以完善续期程序,减少重复申请。

在疫情期间被纳入医疗保险范围的远程医疗服务,将继续作为保险项目,直至2024年12月。医疗保险还将行为和精神远程医疗服务作为一项永久性福利。

结束紧急状态还意味着联邦政府将不再承担新冠疫苗和治疗费用。但4月,拜登政府公布了一项规模达到110亿美元的公私合作“补助连接通道项目”,通过各州和地方卫生部门和药店为无保险人群免费提供新冠疫苗和治疗。有保险的人群根据保险类型,可能会产生自付费用。

结束紧急状况取消了对出入境的疫情防控限制。大批移民聚集在美墨边境,预计将在未来几周入境美国,这将令已经不堪重负的医护人员和设施更加紧张。

3. 结束紧急状态对于疫情的状态意味着什么?

政府宣布进入大流行状态意味着经过评估后,确认一种疾病,无论是已知疾病还是新型疾病,都具有“特别强大的”向人传播的能力,对美国两个或更多州构成公共卫生风险,而且需要国际合作控制其传播。但宣布紧急状态结束并不意味着一切恢复正常。

2023年5月3日发布的最新版全球新冠疫情长期疾病管理指南呼吁各国“保持足够的能力、作战准备和灵活性,在新冠疫情爆发期间能够大规模响应,同时维持其他必要医疗服务,为应对更严重或更强大的新病毒变种做好准备。”

前白宫新冠疫情响应协调官德博拉·伯克斯最近警告,奥密克戎变异株仍在继续变异,可能对目前的治疗药物产生抗体。她呼吁联邦政府资助更多对治疗药物和效果更持久的疫苗的研究,提供对许多变异株的保护力。

在伯克斯发出警告的同时,有多个州已经不再召开新冠疫情新闻发布,并关闭了接触风险通知系统,联邦政府也停止了免费居家新冠检测项目。

随着紧急状态结束,美国疾病预防控制中心(CDC)也将公布新冠数据的方式,转变为“持续全国新冠监控”模式。随着紧急状态结束,新冠监控和宣传策略的调整意味着病毒不再是媒体关注的对象,尽管它并没有从我们的生活和社区中消失。

4. 各州和地方的疫情防控措施会受到哪些影响?

联邦政府宣布结束紧急状态,并不影响各州或地方层面宣布紧急状态。各州宣布进入紧急状态,可以分配资源满足疫情防控的需求,其中包括相关规定,一旦新冠病例增多可以做出响应,由其他州的医生和其他医疗提供商现场或通过远程医疗接诊。

但美国大多数州都结束了当地的公共卫生紧急状态。特拉华州、伊利诺伊州、马萨诸塞州、纽约州、罗德岛和得克萨斯州宣布的紧急状态在2023年5月3日依旧有效,将到5月底终止。到目前为止,只有马萨诸塞州州长莫拉·希利表示,将“延长公共卫生紧急状态所带来的”与医疗人员和紧急医疗服务有关的“重要的灵活性”。

有些州可能选择将新冠疫情时期的应急标准作为长期措施,例如放宽对远程医疗和州外医疗提供商的限制等,但我们认为无论是政客还是公众,需要很长时间才能重新接受与新冠直接相关的任何紧急命令。(财富中文网)

本文为2023年2月3日发表的原文的更新版本。

玛丽安·莫泽·琼斯现任俄亥俄州立大学(The Ohio State University)医疗服务管理、政策与历史副教授,埃米·劳伦·费尔柴尔德现任俄亥俄州立大学公共卫生系主任兼教授。

本文依据知识共享许可协议转载自The Conversation。阅读原文。

翻译:刘进龙

审校:汪皓

Ending the federal emergency reflects both a scientific and political judgment that the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis has ended and that special federal resources are no longer needed to prevent disease transmission across borders.

The COVID-19 pandemic’s public health emergency status in the U.S. expires on May 11, 2023. And on May 5, the World Health Organization declared an end to the COVID-19 public health emergency of international concern, or PHEIC, designation that had been in place since Jan. 30, 2020.

Still, both the WHO and the White House have made clear that while the emergency phase of the pandemic has ended, the virus is here to stay and could continue to wreak havoc.

WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus noted that, over that time, the virus has taken the lives of more than 1 million people in the U.S. and about 7 million people globally based on reported cases, though he said the true toll is likely closer to 20 million people worldwide. While the global emergency status has ended, COVID-19 is still an “established and ongoing health issue,” he said.

The Conversation asked public health experts Marian Moser Jones and Amy Lauren Fairchild to put these changes into context and to explain their ramifications for the next stage of the pandemic.

1. What does ending the national emergency phase of the pandemic mean?

Ending the federal emergency reflects both a scientific and political judgment that the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis has ended and that special federal resources are no longer needed to prevent disease transmission across borders.

In practical terms, it means that two declarations – the federal Public Health Emergency, first declared on Jan. 31, 2020, and the COVID-19 national emergency that former President Donald Trump announced on March 13, 2020, are expiring.

Declaring those emergencies enabled the federal government to cut through mountains of red tape to respond to the pandemic more efficiently. For instance, the declarations allowed funds to be made available so that federal agencies could direct personnel, equipment, supplies and services to state and local governments wherever they were needed. In addition, the declarations made funding and other resources available to launch investigations into the “cause, treatment or prevention” of COVID-19 and to enter into contracts with other organizations to meet needs stemming from the emergency.

The emergency status also allowed the federal government to make health care more widely available by suspending many requirements for accessing Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Program, or CHIP. And they made it possible for people to receive free COVID-19 testing, treatment and vaccines and enabled Medicaid and Medicare to more easily cover telehealth services.

Finally, the Trump administration used the national emergency to invoke Title 42, a section of the Public Health Service Act that allows the federal government to stop people at the nation’s borders to prevent introduction of communicable diseases. Asylum seekers and others who normally undergo processing when they enter the U.S. have been turned away under this rule.

2. What domestic policies are changing?

An estimated 15 million people are likely to lose Medicaid or CHIP coverage, according to the federal government. Another analysis projected that as many as 24 million people will be kicked off the Medicaid rolls.

Before the pandemic, states required people to prove every year that they met income and other eligibility requirements. This resulted in “churning” – a process whereby people who did not complete renewal paperwork were being periodically disenrolled from state Medicaid programs before they could reapply and prove eligibility.

In March 2020, Congress enacted a continuous enrollment provision in Medicaid that prevented states from removing anyone from their rolls during the pandemic. From February 2020 to March 31, 2023, enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP grew by nearly 23.5% to a total of more than 93 million. In a December 2022 appropriations bill, Congress passed a provision that ended continuous enrollment on March 31, 2023.

The Biden administration defended this time frame as sufficient to ensure that patients did not “lose access to care unpredictably” and that state Medicaid budgets – which received emergency funds beginning in 2020 – didn’t “face a radical cliff.”

But many people who have Medicaid or who enrolled their children in CHIP during this period may be unaware of these changes until they actually lose their benefits over the next several months.

At least five states already began disenrolling Medicaid members in April. Other states are sending out termination letters and renewal notices and will disenroll members starting in May, June and July.

Only Oregon has set up a comprehensive program to minimize disenrollments. That state is running a five-year federal demonstration program that allows it to temporarily let people stay on Medicaid if their income is up to 200% of the federal poverty level and lets eligible children stay on Medicaid through age 6. Many other states are trying more limited strategies to improve the renewal process and decrease churning.

The array of telehealth services that Medicare began covering during the pandemic will continue to be covered through December 2024. Medicare is also making coverage for behavioral and mental telehealth services a permanent benefit.

The end of the emergency also means that the federal government is no longer covering the costs of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments for everyone. However, in April, the Biden administration announced a new $1.1 billion public-private “bridge access program” that will provide COVID-19 vaccines and treatments free of charge for uninsured people through state and local health departments and pharmacies. Insured individuals may have out-of-pocket costs depending on their coverage.

The end of the emergency lifts the pandemic restriction on border crossing. Large numbers of migrants have gathered at the Mexico-U.S. border and are expected to enter the country in the coming weeks, further straining already overwhelmed staff and facilities.

3. What does this mean for the status of the pandemic?

A pandemic declaration represents an assessment that human transmission of a disease, whether well known or novel, is “extraordinary,” that it constitutes a public health risk to two or more U.S. states and that controlling it requires an international response. But declaring an end to the emergency doesn’t mean a return to business as usual.

New global guidelines for long-term disease management of COVID-19, released on May 3, 2023, urged countries “to maintain sufficient capacity, operational readiness and flexibility to scale up during surges of COVID-19, while maintaining other essential health services and preparing for the emergence of new variants with increased severity or capacity.”

Former White House COVID-19 response coordinator Deborah Birx recently warned that the omicron COVID-19 variant continues to mutate and may become resistant to existing treatments. She called for more federally funded research into therapeutics and durable vaccines that protect against many variants.

Birx’s warnings come as remaining states have ended their COVID-19 press briefings and shut down their exposure notification systems, and the federal government has ended its free COVID-19 at-home test program.

With the end of the emergency, the CDC is also changing the way it presents its COVID-19 data to a “sustainable national COVID-19 surveillance” model. This shift in COVID-19 monitoring and communication strategies accompanying the end of the emergency means that the virus is disappearing from the headlines, even though it has not disappeared from our lives and communities.

4. How will state and local pandemic measures be affected?

The end of the federal emergency does not affect state-level or local-level emergency declarations. These declarations have allowed states to allocate resources to meet pandemic needs and have included provisions allowing them to respond to surges in COVID-19 cases by allowing out-of-state physicians and other health care providers to practice in person and through telehealth.

Most U.S. states, however, have ended their own public health emergency declarations. Six states – Delaware, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island and Texas – still had emergency declarations in effect as of May 3, 2023, that will expire by the end of the month. So far, Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey stands alone in having indicated that she will “extend key flexibilities provided by the public health emergency” related to health care staffing and emergency medical services.

While some states may choose to make permanent some COVID-era emergency standards, such as looser restrictions on telemedicine or out-of-state health providers, we believe it could be a long time before either politicians or members of the public regain an appetite for any emergency orders directly related to COVID-19.

This is an updated version of an article that was originally published on Feb. 3, 2023.

Marian Moser Jones, Associate Professor of Health Services Management, Policy and History, The Ohio State University and Amy Lauren Fairchild, Dean and Professor of Public Health, The Ohio State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.