NIHCM基金会(NIHCM Foundation)为本文的报道慷慨地提供了资助。

天气预报显示有小概率会出现雷雨天气。

在2020年8月10日早间,艾奥瓦州的气象专家贾斯汀·格力桑倒是对这场雨给予了厚望,这里干旱的土地迫切需要饱饮一场雨水。在当天上午与农田农艺师通话时,他还表示自己希望从内布拉斯加远道而来的风暴线亦能光顾艾奥瓦州的上空。

尽管经历了该州历史上最湿润的两个年份,以及去年春天理想的种植条件,但入夏后的这几个月一直温暖多风。到了2020年8月,严重的干旱席卷了艾奥瓦州的中西部地区。

格力桑隶属于艾奥瓦州的农业与土地管理部。在实地考察中,他发现一个有警示意味的迹象,当地的作物出现了生理应激反应:作物开始“燃烧”,其位于底部的叶片开始变得脆黄,也就是植物在自闭生机以节约水分。与此同时,大豆的叶片在日间也翻转了过来,以尽量保留水分。

整个夏天,格力桑看到,并不是没有风暴靠近这个地区,但只要一碰到干燥的空气就会偃旗息鼓。该州的农场极度地渴望雨水的浇灌。

在2018年格力桑成为州气候学家之前,他曾经是艾奥瓦州立大学的一名大气研究科学家,致力于搭建区域气候模型并研究大气的流体动力学。每天,他都会从系统和参数方面来思考大自然母亲的行为。

然而,无论是自己的工作、博士学位还是两个气象学学位,都未能让格力桑为当天突然降临艾奥瓦州的这个自然现象做好准备。

在位于得梅因的家中露台上,他亲眼目睹了风暴的到来。当看到一堵如夜般漆黑的云墙时,他匆忙向地下室跑去,刚跑到一半,一根树枝砸到了他的房子上,扯出了煤气总管,安全警报响起,随即电也停了,时间刚好是上午11点过4秒。

在接下来的两个小时中,格力桑目睹的这场强度和破坏力极强的“巨型”风暴席卷了整个艾奥瓦州。风暴过后,到处都是倒下的大树和电线杆、掀翻的牵引式挂车、扭曲的谷仓、倒伏的作物以及残破的住宅和企业。

美国国家海洋与大气管理局的数据显示,在风暴于艾奥瓦州平息后,也就是其肆虐了14个小时以及770英里的距离之后,造成了约110亿美元的损失,成为了美国历史上破坏力最强的雷暴天气。

在风暴峰值期间,艾奥瓦州当天阵风的风速超过了140英里/小时,这在美国中部地区实属罕见,以至于美国国家航空航天局和格力桑都在研究灾后照片,以弄清楚风暴的起因。

虽然艾奥瓦州到处都是十分留意天气变化的农民,但这场灾难(很多艾奥瓦人依然将其描述为“内陆飓风”)似乎完全没有先例可循,而且不应该出现在这个世界上。

事实上,它是一种德雷科风暴,这个词由艾奥瓦州的首位官方天气观察家盖斯塔乌斯·德特勒夫·亨瑞奇斯杜撰于19世纪80年代。这位脾气不好、十分博学的教授曾经帮助编纂了元素周期表,他认为应该用一个术语来描述艾奥瓦州这种直线型的大风,以区别于旋风(例如龙卷风)。他选择了西班牙术语“德雷科风暴”(意为“直的”)。

如今,德雷科风暴的定义是:波及距离至少240英里,且持续风速超过58英里/小时的风暴。尽管这类风暴在艾奥瓦州大概每两年会发生一次,但该州了解这一术语的人并不多。

即便常驻美国联邦应急管理局堪萨斯城办公室的资深灾害协调员杜维恩·特维斯亦承认自己此前从未听过这个术语。他负责领导该机构在艾奥瓦州的赈灾行动。

当然,龙卷风是这片平原地区常见的灾害,异常恐怖而且破坏力极大。然而,它在其破坏的路径上存在时间短,且范围有限。

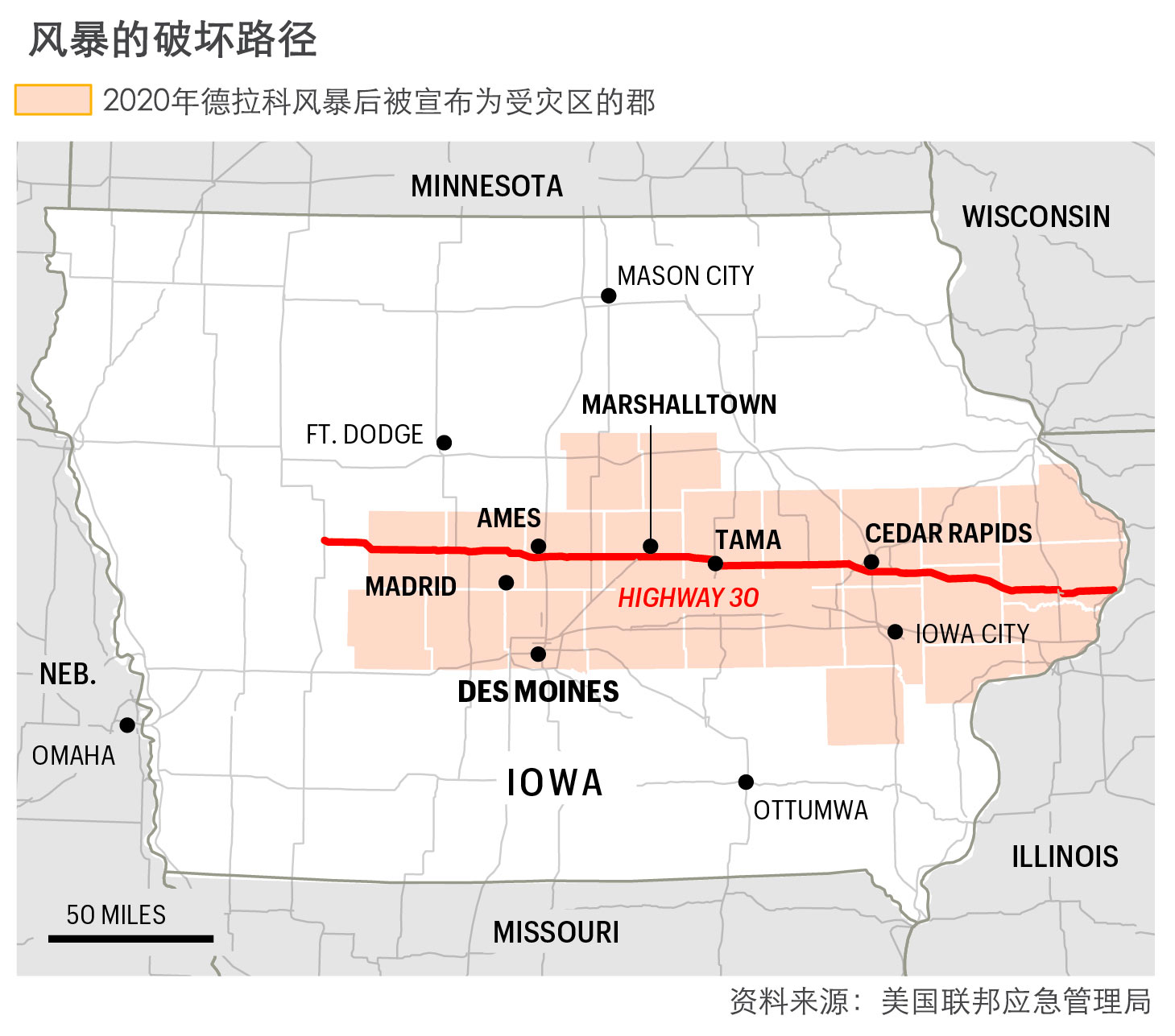

德雷科风暴的持续时间更长,而且波及范围更大,这次的风暴更是如此,基本上沿着30号高速公路(也就是老林肯高速公路)和80号州际公路一直向东,在艾奥瓦州的波及宽度达到了90英里,其中包括农场、少数肉类加工城镇、艾奥瓦州两个最大的大学校区(艾姆斯市和艾奥瓦市)以及艾奥瓦州最大的两座城市(得梅因和锡达拉皮兹)。

像格力桑一样,艾奥瓦州人或多或少对这场风暴没有什么准备。德雷科风暴尤为复杂,它属于临时出现的风暴系统,很难提前很长一段时间进行预测。

大多数受灾的艾奥瓦人在当天听到的是标准的8月天气预报,然后开始做自己的事情,没有丝毫信息提示他们只有数个小时的时间去躲避时速达到100英里的大风天气,更不用说在一周多的时间内连生活用电都没有。

本顿郡的第四代农民本·奥尔森当天来到了田间施肥;锡达拉皮兹一家餐馆的老板威利·费尔利正在为其牛排屋采购物资;锡达拉皮兹一家企业的老板史蒂夫·史瑞夫正在与母亲共进午餐;马歇尔敦的一名社会工作人员玛利亚·冈萨雷斯刚刚走出家门遛狗,而她的丈夫则去了银行。

作为本顿郡农村地区五个天主教教区的牧师,神父克雷格·思特梅尔从锡达拉皮兹地区办事归来,这时天空暗了下来。

他在诺威市的家就在圣迈克教堂的旁边。很快,他发现一个垃圾桶从窗前飞过,然后圣迈克教堂34米高、有着140年历史的塔尖空降在了自家院子里。风暴继续肆虐了30分钟,他担心自己的房子会被吹垮。教堂不会也被吹翻吧?

“真是太离谱了。”他说道。

此次风暴是一场悲剧。然而,它的影响远不止如此。

它是各种灾难的大碰撞——席卷美国中部地带的极端天气事件、让经济受到严重冲击的新冠疫情以及去年夏季两党的针锋相对。对很多人来说,他们在德雷科风暴到来之前便已经深陷难以承受的困苦和压力。

对当地的卫生官员来说,控制肆虐的疫情已然让他们抓狂,而风暴的出现则让抗疫任务变得更加复杂。对领导者来说,这场风暴为新冠疫情中社会经济平衡举措又增添了几分重担。

虽然将艾奥瓦州遭受的真实灾害简化为符号有失公允,但在2020年8月10日,有鉴于其被移平的农田、爆炸的谷仓,艾奥瓦州看起来就像是美国毛毡。

提到艾奥瓦州,美国其他地区的人都会联想到平坦、一望无际的玉米地和农场;对于很多白人来说,这是一片只是在飞机上俯瞰过的“飞越之地”。

然而,如今的艾奥瓦州要远比这个老旧的刻板印象复杂的多,也更加多元化。与美国各地一样,艾奥瓦州处于不断的变化之中,而且充满了压力和矛盾。

作为美国玉米、热狗和大豆最大的生产地,艾奥瓦州的经济动力依然来自于农业和相关加工业。然而,随着这些行业削减冗员,艾奥瓦州的增长引擎已经转变为人口更多的市区,支撑行业包括银行、保险、商业服务和医疗保健。

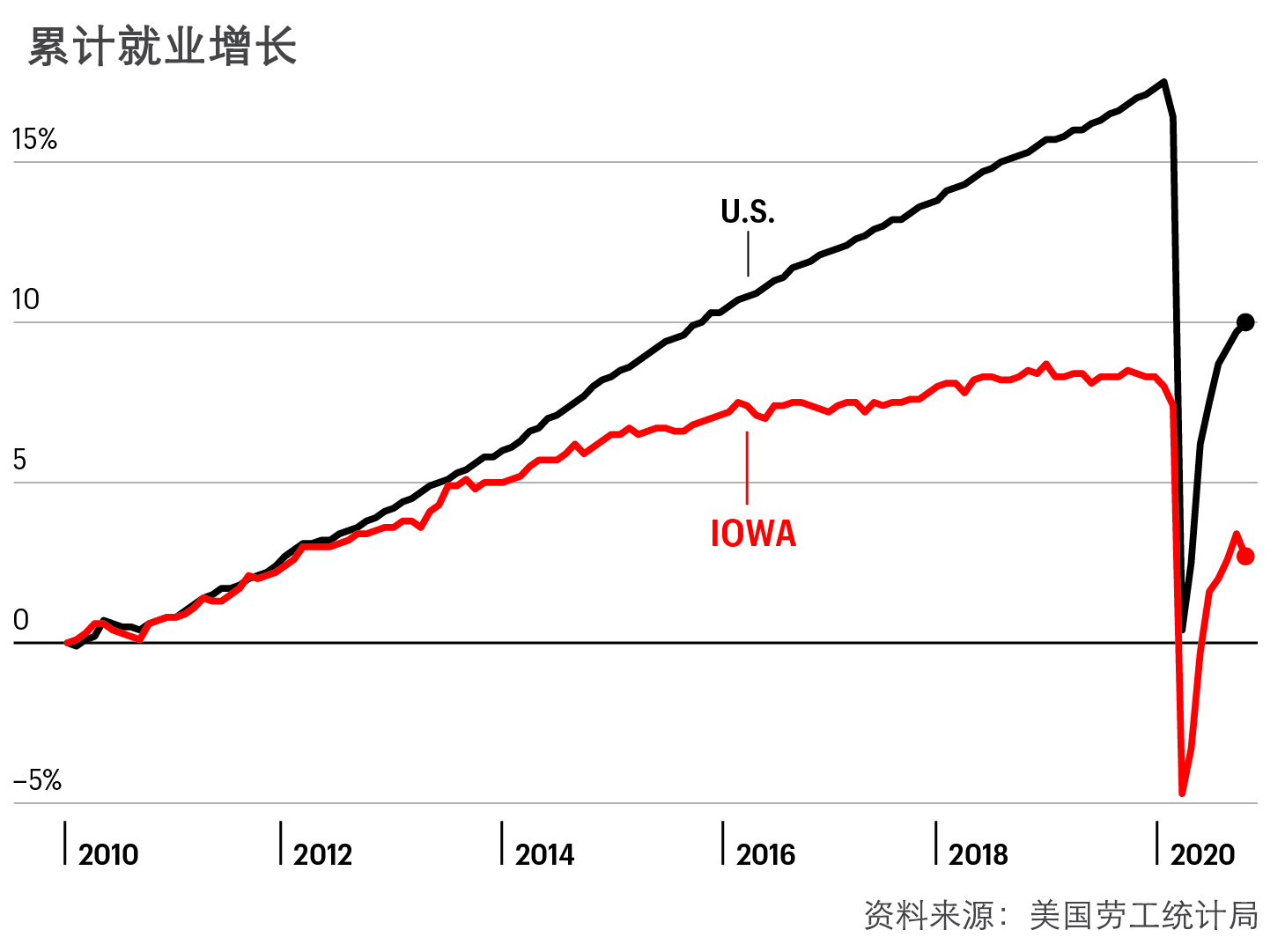

艾奥瓦州有着全美最高的劳动参与率,这个平原州的许多中老年妇女仍然在工作,但其实该州的就业机会并不多,跟不上高技能员工的供应速度。

确实,艾奥瓦州培养的大量人才都流向了外地。艾奥瓦州立大学的经济学家大卫·斯文森说:“艾奥瓦州在教育领域投入了大量的精力。然而,我们的经济却由重负载生产、加工以及农业构成,以至于我们培养了如此多的人才,却没有用武之地。”

在过去10年中,艾奥瓦州的99个郡中有77个郡存在人口流失现象,其中包括众多农村郡,同时也包括城乡结合部的郡,也就是“居住区”,这些都是依赖于制造业的城市,人口在1万至5万之间,而且一直都在削减工作岗位,其当前的城市范围比其经济规模还要大。

这种现象恰好体现了该州不断加深的城乡分化,而且这种分化在该州传统的紫色政治路线中越发明显。

2016年和2020年,艾奥瓦州选择支持了唐纳德·特朗普,但在2020年,支持特朗普的选票更多来自于农村地区。与全美其他地区一样,艾奥瓦州的红色阵营变成了深红,而其蓝色阵营则变成了深蓝。在高层方面则是红色占优:如今,艾奥瓦州的州长、两位参议员以及四名众议员中的三名都是共和党人。

自从进入2020年以来,艾奥瓦州的整体经济没有多少起色。

“基本上处于停滞状态。”斯文森说道。在疫情爆发初期,艾奥瓦州的失业率像美国其他地区一样一路高歌,但自此之后降至3.6%。

斯文森指出,这则消息实际上并没有它表面上看起来的那么美好:艾奥瓦州的就业岗位在去年并没有增加,而是出现了劳动力流失。斯文森怀疑流失的那部分劳动力多数都是需要照看孩子的妇女,或者是因为疫情相关的安全问题而提前退休的员工。

所以可以预见的是,要想知道艾奥瓦州是如何度过2020年,以及该州所有猝不及防的灾难的,不同的地域和不同的询问对象会给你不同的答案。

因此,本文将众多独立的故事融合在一起,而且都与德雷科风暴有关,从西部一直到东部。

它所揭示的画面,尽管在一定程度上为艾奥瓦人所独有,但从根本上来看却是2021年美国大众的写照。它所讲述的这个社会正在尽全力解决一系列复杂、紧密相连的问题,例如新冠疫情和气候变化、动荡的经济与人口、因为政治而极端分化的公众。

由于处在美国版图的正中央,艾奥瓦州自然而然地就像是整个国家的一个缩影。该州所面临的问题,也正是当前美国所面临的核心问题:如何平衡公共卫生与经济的关系?如何平衡个人自由与大众利益之间的关系?如何平衡恐惧和科学与盲目的确信和信仰?

简而言之,艾奥瓦州能够为美国的继续前行提供哪些借鉴?

与众多的百姓一样,我在2020年没少担惊受怕。小题大做一直是我的强项。

因此在去年年初,当知名传染病专家迈克·欧斯特霍尔姆对我说,预计最开始在中国爆发的新冠病毒会像风一样传播时,我立马就想到了我的父母,他们都已经年过七旬,住在锡达拉皮兹,其中还有一个抽了一辈子烟。

我对我的同事说,我担心自己的父母会感染病毒,他们笑了。在艾奥瓦州染病?这是美国最安全的地方。

那时还处于2月的慌乱时期,当时,我们没有想到的是,美国政府竟然耗费了数亿美元将海外美国公民撤回美国。就像这些人可以跑的比病毒还快,且美国国界能够免受感染一样。

新冠疫情也确实侵入了艾奥瓦州。病例最先出现在3月,一群富有探险精神的老年旅行团队在埃及尼罗河的邮轮上感染了病毒。不过,也有可能新冠病毒当时已然在鹰眼州传播开来了。

一开始,艾奥瓦州像美国其他地区一样,对新冠病毒做出了反应,紧急关闭了学校、电影院、教堂、酒吧、室内餐饮店、理发店和日光浴沙龙。

艾奥瓦州的州长金·雷诺兹,一位担任这一职务四年的保守派共和党人,在3月17日宣布该州进入公共卫生紧急状态。然而,她并未下达居家隔离令,而全美像她这样做的州长也没有几位,这也让艾奥瓦州比大多数州显得更加亲商。

我给父母寄去了N95口罩外加脉动血氧计,我要求他们定期使用,并且提出了一个强烈、必然令人反感的建议:他们应该把测得的数据告诉我。(然而他们并没有。)我们每周都会在Zoom上视频,此举在一定程度上让人感到安心。

艾奥瓦州的人口有320万,就人口密度而言在美国排名第35位,并不是特别大。

然而,在疫情最初的几周中,艾奥瓦州出现了令人担忧的病例数量,其中大部分都与肉类加工厂和养老院有关联。那些特定行业的员工和身体虚弱的人成为了新冠病毒的入侵对象。

艾奥瓦州的经济学家斯文森说:“艾奥瓦州在权衡之后的决定是,该州更希望保全经济,而代价便是劳动力的健康和福祉。”

这个浮士德式的交易导致了病毒的区域性传播,也让其他企业成为了牺牲品。

本顿郡的农民本·奥尔森有200头待出栏的牛,准备于3月31日运往附近的泰森公司的工厂。这些牛的价值共计数十万美元,而且耗费了7个月的投资才将其体重从800磅养到了上市恰好所需的重量——1500磅。

他在发运前12个小时接到了电话:工厂爆发了疫情,得再等等。两周后疫情再次爆发,他一个月后以十分糟糕的价格出售了其过重的牛。

艾奥瓦州的养猪户也面临着同样的两难境地。由于猪肉无人问津,一些养猪户不得不对猪实行安乐死。

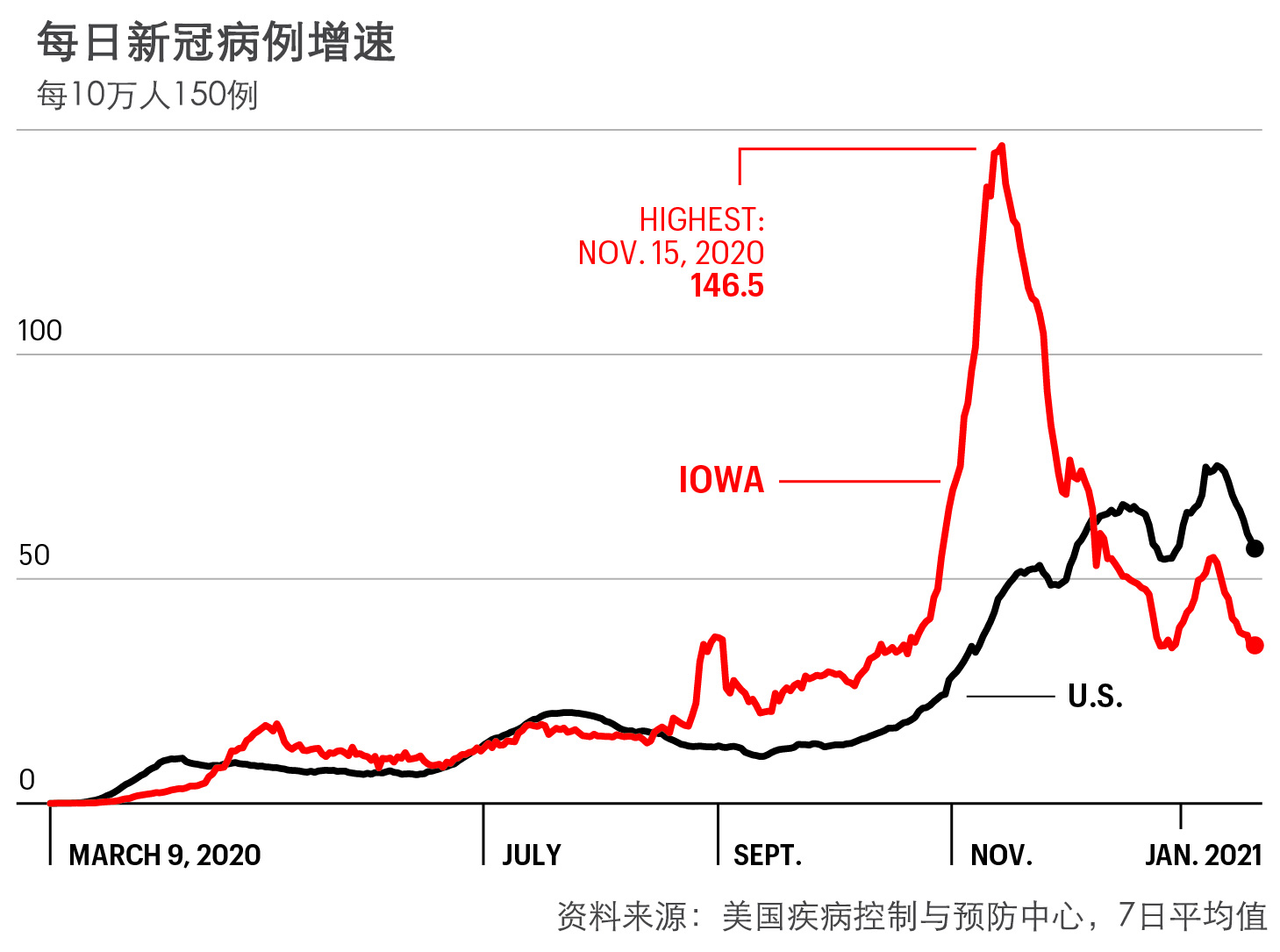

该州的病例增长曲线直到5月中旬封锁令解除之后才出现平缓迹象,而且形势自此之后变得越发糟糕。

当地媒体和公共医疗界曝光的很多事情,让人们对该州疫情应对举措的信心大减。例如该州的主要检测机构由一家没有经验的犹他州初创企业经营,而且该企业似乎是因为与艾奥瓦州人气明星之子阿什顿·库切尔之间的关系,才获得了这项未经投标的合约。

最重要的是,雷诺兹在一场又一场的新闻发布会上坚决认为,应对疫情的最佳方式就是让艾奥瓦州负责任的人民自行应对。该州无需命令其市民如何去做,因为她信任他们会做出正确的选择。她也不会发布“口罩令”,也不会授权该州的任何市长下达此类命令。

当时,我的父亲依然对秋天去观看艾奥瓦州橄榄球赛抱有很大的希望,然而,他在体育馆置身于一大群无口罩人群中间的景象,成为了当时我最担心的新冠疫情传播场景。

然后,在8月10日的下午,我的母亲群发了一个消息说:“我们十分安全(后面加了一个做祈祷的表情)……”上面有多张照片,差点没有认出来是他们的后院。

“龙卷风?”我妹妹发消息问道。

住址离我父母只有一个街区的弟弟发消息说是“陆地飓风”。

在这之后,电力或信号都断了,也无法再联系。然后在接下来的48小时中,锡达拉皮兹就像是被风从地球上刮走了一样。

社交网站上流传着几段有关这次强风暴的短视频。然而,芝加哥除了提及风灾之外,就再也没有给出更多有关该事件的信息。

锡达拉皮兹并没有从地图上消失,然而,它与其他数百个社区一样,因为风灾而失去了电力。

锡达拉皮兹的整个都市区及其约13.2万人口都因为风灾而断电。(整个艾奥瓦州有68万人口无电可用。)由于信号塔被吹倒,一些人连通信信号都没有。

位于锡达拉皮兹市中心的两家医院中的其中一家——圣卢克医院,在长达51个小时的时间中完全变成了一座孤岛,互联网、电子病例档案、地上通讯线以及所有三家锡达拉皮兹的移动运营商的服务都消失了。与此同时,在风暴和废墟清理过程中受伤的艾奥瓦州东部民众则蜂拥至急救室。风灾过后,前往医院就医的人数是平常的两倍。

锡达拉皮兹UnityPoint医院的总裁兼首席执行官米歇尔·尼尔曼对我说:“这可能是我作为医院管理者所经历的最可怕的时刻。”

评估受灾程度在锡达拉皮兹尤为困难。除了失去电力和通信之外,人们在一开始很难进入这个地区,因为到处都是残砖断瓦和倒塌的大树。(作为“美国树城”,锡达拉皮兹在风暴中估计损失了65%的树木。)

人们很容易将德雷科风暴看作是气候变化所引发的自然伟力的宣泄,特别是锡达拉皮兹这个受灾最严重的城市在前不久才从一次反常的、500年一遇的洪灾中恢复过来。

2008年的这场洪灾摧毁了该市市中心的大部分地区,以及相当一部分经济适用房。

气候学家格里桑对我说,我们很难将单一极端天气事件与气候变化进行关联。然而,有大量不起眼的证据显示,艾奥瓦州的天气正在改变而且增加了德雷科风暴这样破坏性风暴发生的概率。

格里桑的大部分工作是帮助农民应对现实,例如应对更加频繁的大雨。(艾奥瓦州24小时内降雨量超过10厘米的概率,是过去30年中概率的三倍。)

在2020年的艾奥瓦农场和农村生活调查中,81%的农民表示,他们认为气候变化正在发生,较2011年的68%有所增长。而艾奥瓦州普通民众中有67%的人认为全球正在变暖。(这一比例在全美是72%。)

在我父母于黑暗中应对德雷科风暴灾后事宜的那10天中,我与他们交流的机会并不多。在我尝试与他们通话的大多数时间里,他们都曾经抱怨这是在耗费其手机电量,这一点我十分理解,因为他们目前很不容易。我的母亲在谈论朋友、家人和陌生人这些志愿者时,偶尔会感动得掉眼泪,他们会拿着电锯过来帮忙。

我的家人十分幸运,因为倒在屋顶上的树没有造成太大的破坏。我的父母更换了新屋顶,保险公司承担了这笔费用。我的弟弟在今年春天也会更换新的屋顶。

我从他们和锡达拉皮兹的其他人那里感受到,德雷科风暴之后最困难的一件事情就是直面惨痛的损失继续生活,这座满目疮痍的城市仿佛时时刻刻在提醒人们这一年生活的艰辛。我在去年12月到访该城市的时候也切身体会到了这一点。

德雷科风暴所过之处可谓是哀鸿遍野。在得梅因以北48公里的马德里德,风暴掀翻了养老中心Madrid Home这栋四层楼建筑的屋顶,那里有6位新冠患者在顶层接受隔离治疗。

该中心的经营者、Western Home Communities公司的首席执行官克里斯·汉森在参加线上会议时,收到了其马德里德执行总监惊慌失措打来的电话。

汉森的所在地位于马德里德的东北部,距离马德里德有一个小时车程,当时该地区的天空依然晴朗,因此这对汉森来说是一个不可思议的反转。

Western Home在艾奥瓦州有10个养老中心社区,疫情给该公司带来了严峻的考验,其中既有长期护理设施所面临的共性问题(例如缺乏个人防护用品和员工),也有艾奥瓦州独有的问题。

他说:“有几次,我对州长感到十分失望,因为她没有拿出勇气去发布口罩令。”他还表示,自己感觉艾奥瓦州选择了保全经济而不是保护老年人。

“这并非是什么迫不得已的情形,为什么要将所有人置于危险境地?我们的雇员依然待在社区中,他们没得选择。”

在7月底,位于马德里德的Western Home出现第一例新冠病例之前,该公司的经营设施有效地抵御了新冠疫情的爆发。

而该公司的一位医生在公司出诊时将病毒带了进来。在这几天时间中,该中心一楼有6位病人和3名员工被检测出新冠阳性。这对员工的士气来说是个打击。

汉森说:“他们感到十分自责,因为他们觉得自己失败了。”汉森与全美其他医疗和长期护理服务提供商一样,一直在与员工严重短缺问题做斗争。

这个秋季给Western Home带来了巨大损失和恐慌。在公司旗下的一些管理式医疗机构中,有近100%的居民新冠检测呈阳性,而负责照看他们的员工在检测中亦呈阳性。

他对我说:“真的是太恐怖了,我的雇员也有他们的家人。”

最大的挑战在于控制痴呆老人部门的疫情传播。在位于艾奥瓦州克雷斯科市的一所小型养老院中,24位居民里有8位因为新冠肺炎而丧生。他在谈到艾奥瓦州松懈的病毒防范措施时说:“我们亲眼目睹了这类举措的后果。”

当我在今年1月中旬与汉森交谈时,他的员工和居民依然在等待疫苗。

汉森说:“疫苗的推广速度与我们的期望值相距甚远。”他批评的并非是州政府,而是联邦政府,后者正在私营领域的长期护理机构中推广疫苗。

“这并不仅仅是协调不到位的问题。说真的,由于风险迟迟得不到控制,我们之中很快就会有人因此而丧生。”

汉森依然对艾奥瓦州的疫情动态感到十分失望。他注意到,在我们谈论的前一天,数百名不戴口罩的艾奥瓦人汇集在艾奥瓦州议会圆形大厅(州立法人员无需佩戴口罩,而且很多人都没有戴),举行“艾奥瓦州知情选择”集会活动。该集团呼吁终止新冠疫情强制令。

汉森说:“我不知道在整个疫情期间,人们的常识都发生了什么变化?这件事情最终竟然演变成了政治事件,真的让人感到无语。”

在德雷科风暴到来之时,我依然在担心新冠疫情,而且是变得更加担心。艾奥瓦州人会告诉你,灾难会让他们团结一心。然而,这种善意却在助长病毒的传播。

圣卢克医院的尼尔曼说,锡达拉皮兹的新病例的确在德雷科风暴发生之后的恢复过程中略有抬头,但局势倒是没有她此前担心的那么糟糕。

她对我说:“戴口罩的人大幅减少。说实话,人们不得不为了不同层次的需求而工作。”

然而,更糟糕的情形还没有到来。

在去年秋季的大部分时间里,艾奥瓦州的确诊人数在全美新冠疫情图表中一直名列前茅。病毒四处散落,农村郡受到的冲击尤为严重。尽管越来越多的公共卫生部门都在呼吁,但州长雷诺兹依旧只是要求艾奥瓦州民众要负起责任。

随着病例增长曲线的下滑,州长自己与特朗普总统一道出现在演讲台上,没有戴口罩,台下则是得梅因数万名特朗普的支持者。

2020年11月,艾奥瓦州的医疗机构宣布,他们的接纳能力已近饱和,而且缺乏员工或床位来接收更多的新冠患者。

作为应对举措,州长发布了一系列复杂的规定,旨在控制疫情传播:每个孩子在体育比赛中的陪同观众不得超过两名;在室内聚会超过25人,或室外聚会超过100人的场所,必须在面部佩戴覆盖物。

最终,在感恩节之前,雷诺兹以一种乞求原谅的口吻——“没有人愿意这样做……我也不愿意”——发布了全州强制口罩令,只不过附加了一些例外条件。

在马歇尔敦市的市长乔尔·格利尔看来,政府早就应该发布口罩令。格利尔白天还从事律师工作,他看到了其社区自去年早春以来所面临的新冠疫情压力。

马歇尔敦市有2.8万人口,恰好位于艾奥瓦州的中心位置,是一个肉类加工业城市。与其他艾奥瓦州的城市一样,它的猪肉加工厂和最大的雇主JBS很早便出现了疫情。有数十人在去年4月初被检测出阳性,一名当地雇员在5月退休前一周去世。

疫情并未停止蔓延。对格利尔来说,令他感到沮丧和心碎的是,他所在的郡曾经一度是艾奥瓦州受冲击最严重的郡之一,而艾奥瓦州是美国受冲击最严重的州之一。

格利尔会定期与艾奥瓦州中部地区的多名市长召开Zoom会议。很多人都希望发布口罩令,然而,他们并没有权力来做此事。有一些市长则不顾一切地发布了这一命令。

格利尔不愿意越过其法定权力,只是发布了一个市长公告,要求市民覆盖面部,但也警告不得强制执行。而此公告并没有得到市民的重视。

10月,格利尔走进了一家当地酒吧去取外卖订单。酒吧里人群窜动,虽然员工都戴着口罩,但戴口罩的顾客只有他一人。

其他顾客开始嘲讽他的行为,并说他不像个男人。

格利尔告诉我说:“这些人的科学考试肯定不及格,无法跟他们讲道理。”

马歇尔敦市的服务生便成为了配戴口罩分歧的牺牲品。

La Carreta Mexican Grill餐厅的老板、31岁的阿尔方索·梅迪纳在11月的最后一周便染上了新冠病毒。这家餐厅是该城市颇有人气的美墨边境菜餐厅。他失去了味觉和嗅觉,他估计,在去年那个时候,其餐厅的17名服务生中有百分之八九十都已经出现了这一症状。

自去年3月以来,他的团队在餐厅尝试了保持社交距离,并采取了预防措施。他们佩戴了口罩,但顾客几乎都没有戴口罩。

梅迪纳在1月初对我说:“客户无需戴口罩,但病毒基本上就是这么传播的,真的很令人沮丧。所有人本来应该都戴口罩,但我们知道感染病毒只是迟早的事情。”

尽管马歇尔敦市的多家大型卖场,例如Menards和沃尔玛在疫情初期便开始要求覆盖面部,然而由于没有州强制令,同时作为一家少数族裔持有的企业,梅迪纳认为在La Carreta餐馆很难强制推行佩戴口罩的政策。

他的雇员,尤其是那些兼职工作的高中生,在与顾客打交道时也心怀感染病毒的恐惧。他希望顾客可以担负起责任。

“如果你来这里吃饭,是因为这是你最喜爱的餐馆,那么为什么不能佩戴口罩?”(他说,自从州长发布全州强制令之后,几乎所有人都会佩戴口罩。)

梅迪纳祈祷其员工千万不要一次性全部染病,如果是这样的话,他就得闭店。餐馆在疫情期间的生意非常不错,他将这一业绩归功于酒品外卖销售。

事实上,La Carreta餐馆在2020年的五月五日节那天是有史以来生意最好的节日。

梅迪纳称自己十分幸运,因为他是在生意平平的感恩节感染了病毒,当时,就算他10天不去,也不会对店里的生意有什么影响。

他的大多数雇员都出现过像他这样轻微的症状,而且所有人最终都康复了,然而其团队中几乎每一个人,都有相熟之人死于新冠疫情:梅迪纳在俄亥俄州52岁的叔叔;在墨西哥给梅迪纳父母看病的30岁医生;店里大厨的父亲;两位服务生的祖父;店里的老顾客。

他说:“死神一直都在我们周围。”

梅迪纳出生于弗吉尼亚州的罗阿诺克市,他小时候一直跟随父母(墨西哥移民)辗转于美国各地,并于这一期间开设了多家蒸蒸日上的美国墨西哥边境菜餐厅。

他5岁时来到了艾奥瓦州,不久后搬到了马歇尔敦市。他十分喜欢这里的多元化氛围、自己所接受的良好教育以及大众的友善。

他说:“这是一个适合成长的地方。你知道的,‘艾奥瓦的友好’,你真的能够体验到这一点。”

在疫情爆发之后,梅迪纳注意到他的批发商可以供应众多高需求物品,例如洗手液、大米和豆子、厕纸等。他下了一大批订单,而后开始在当地转售。

他曾经一度向当地养老院提供手套。在整个疫情期间,他向当地的食品募捐活动捐赠了主要原料,并为失去家庭成员的家庭组织了募捐活动。

然而,梅迪纳最出名可能还是那句“没有爱就没有玉米卷”口号,这是今秋他在餐厅门前的告示牌,以及商品上写下的宣传语。

在乔治·弗洛伊德和其他非武装黑人公民在去年夏天遭到警察杀害之后,梅迪纳觉得有责任通过其平台来宣传其作为当地企业主的价值观。他在社交媒体上进行了试验,得到了不错的反响,因此他在自家餐厅La Carreta前放了一块牌子。这块牌子上面写着一些在他看来无可指责的常识性箴言:“黑人的命也是命”、“人权就是妇女的权益”、“科学是真实存在的”。

然而有一天,一位顾客在看到这些标语后,在收据上写下了愤怒的留言,称这些标语不符合基督教义。

梅迪纳在其个人的Facebook页面公布了这张收据的照片,并留言说:“没有爱就没有玉米卷。”

他还创建了打着该标语的网站和在线服装店,呼吁公平和平等,而且建议将总统大选日改为联邦假日,以确保所有人都能够投票。网站所获利润则捐给了梅迪纳此前设立的当地奖学金基金。

他的信息被疯狂转载,尤其是他在去年10月的总统大选预备阶段接受了CNN的专访之后更是如此。对“没有爱就没有玉米卷”帽子和衬衫的订单从全世界蜂拥而至,而且随着人们在11月发布自己的投票照片,很多人都@他们,“#没有爱就没有玉米卷”。他用这笔钱在马歇尔敦市的社区大学设立了14项奖学金。

梅迪纳表示,他也曾经收到过批评信件,而且不只一封,上面的措辞要比促使他发起这一切的收据留言更加激烈。

我问他,新冠疫情和当前的政治气候是否会让艾奥瓦州没有以前那么友好了?他称,自己和雇员在餐厅从来不谈论政治,这是有原因的。

他说:“马歇尔敦市里有些人有着与其他人迥异的观点,而且我尊重每个人的观点。相比我自己,这里的一些客户有着不同的政党背景。我对我的雇员说,不管来店客人拿着什么工具,或其衬衫写着什么内容,‘我们都应该一视同仁地提供五星级服务。’”

市长格利尔发现,自己越发难以保持中立立场。他哀叹到,其城市的疫情已经沦为了一种政治工具。他曾经因为新冠疫情而受到责备,其中涉及电子邮件、短信以及在其市长Facebook页面下的众多留言。

他说:“有一半人对学校开学感到异常愤怒,而另一半则对不开学十分恼火。场面真的很难看。”

格利尔已经上任三年,在这期间,他已经应对了马歇尔敦市一场又一场的灾难。2018年7月的一天,一场龙卷风直接从大街刮过,吹倒了当地政府的钟楼,让历史古迹和市中心企业一片狼藉,随后又摧毁了马歇尔敦市低收入地区数座房屋。这也让德雷科风暴在某种程度上成为了异常残酷的超自然现象。

应对这些灾难的诸多重担落到了金伯利·埃尔德的肩上,她是马歇尔郡的应急管理协调员。她自2003年以来便一直担任这一职务。

然而,灾害似乎一年比一年多,可以用来赈灾的物资却越来越少。

在2020年的大部分时间中,她在办公室之外工作时总是拿着很多盒子。其中一些盒子里装着个人防护用品,她自己会将郡里的库存送到养老院和应急响应员的手中。其他盒子则是文件盒,里面全是文件,也就是灾害过后大量的行政管理工作。

埃尔德两年多以来都没有休过假,而且作为一个只有一名员工的部门,她最害怕自己感染新冠病毒。埃尔德说:“如果我像其他人一样住院了,那他们该怎么办?”

埃尔德并非是唯一一位在恢复过程中陷入困境的人士。

为了从保险公司和州机构获得及时的救援,社区里的某些人付出了更多的努力。与艾奥瓦州其他城市一样,马歇尔敦市尤为多元化。最近的人口调查显示,其30%的人口是西班牙裔人。马歇尔敦市学校区域的学生能够讲40多种语言;幼儿园中的儿童有70%都是非白人族群。

肉类加工工厂进一步助长了这种多元文化主义,因为长期以来,这里的工作吸引了各类人口的到来,包括最近的缅甸和刚果难民。

在引导恢复的进程中,语言障碍是一个问题,另一个问题则是时间。城市的移民人口占马歇尔敦市必要劳动力的很大一部分,这些人所从事的工作通常没有什么灵活性可言,他们连排队等保险理算员的时间都没有。

对于那些梅斯克瓦基族定居地(艾奥瓦州塔马郡占地8000英亩的地界,位于马歇尔敦市的东部,居住着密西西比Sac & Fox部落)的民众来说,因为德雷科风暴而导致的搬迁带来了另一个惨痛的成本:新冠疫情。

作为艾奥瓦州唯一受到联邦政府承认的部落,梅斯克瓦基族于1857年购买了这块土地,他们在此之前曾经反对联邦政府将其流放至堪萨斯城保护区的决定。

多年来,部落拓展了其占有的财产以及定居地,目前居住着约1200名部落成员,拥有其自己的医疗诊所、法院和学校。1992年,梅斯克瓦基族在地界上开设了一家酒店和赌场,并打出了拥有“艾奥瓦州最不牢靠的老虎机”的广告。如今,部落运营70%的资金来自于这座赌场。

定居地共有350处住所,其中271座毁于德雷科风暴,而且风暴过后,拥有发电机的酒店自然也就成为了受影响人群的避难所。

定居地的执行总监劳伦斯·斯波提伯德称,700名部落成员将酒店挤得水泄不通,有的房间甚至住着5至6人。人们发现,过去数月期间与自己保持着社交距离的人,如今就挨着自己。

斯波提伯德说:“人们的互动变得更加紧密,而且也合作的更紧密。为了实现这一点,我们不得不撤离了安保。结果,病例出现了激增。”

定居地在某种程度上与艾奥瓦州的疫情应对举措可谓是背道而驰。

梅斯克瓦基部落医疗诊所的卫生总监卢迪·帕帕基于去年3月发现了该社区的首例新冠病例。一名部落成员因为呼吸问题而上医院就诊,后来在病毒检测中呈阳性。

很快,这位人士的家庭成员及其密接也感染了病毒。有几个病例属于重症,需要住院,有一名老人因为病毒感染而去世。

帕帕基说:“一开始,我们只是一个不大的‘震中’。”他知道这里有很多人都十分脆弱,有些是老年人,有些人存在有健康问题,例如糖尿病和高血压等,因此这群人有着更大的风险。

部落领袖几乎立即做出响应,下达了居家隔离令,关闭了定居地的赌场和其他经营设施。他们继续向雇员支付薪资,并要求他们待在家中。得益于印第安人健康服务,部落成员拥有稳健、可获取的检测基础设施。

当部落在去年夏初再次开放时,其方式异常保守:部落要求公众佩戴口罩,并取消了年度的祈祷仪式以及其他具有重要文化意义的仪式性聚会。

然而这一举措也存在局限性。很多定居地的居民都在塔马、托雷多和马歇尔敦市等附近城市工作,而且所有人都得离开定居地购买百货和其他物资。梅斯克瓦基族切断病毒传播举措的效果,不大可能超过这些周边社区。

斯波提伯德说:“美国有些州对疫情不怎么重视,艾奥瓦州便是其中之一。因此,安保有点无精打采、散漫,而且人们通常不会长时间地戴口罩。”为了工作,斯波提伯德在去年5月从西雅图搬到了这里(他并非是部落成员)。

与众多艾奥瓦州的医疗专业人士一样,帕帕基对雷诺兹州长的疫情应对举措感到非常失望。他会收听州长有关疫情的新闻发布会,但每次都感到沮丧不已,因为州长总是一成不变地坚持认为,她相信艾奥瓦人可以做出正确的抉择。

他说:“很明显,艾奥瓦人做不到,因为我们的病例数在继续飙升。”

他承认,定居地存在一些类似的挑战,社区里也有一些人对于戴口罩令以及如何开展其社交生活的要求十分抵制。

在定居地的一个圣诞集会上,一名感染者传染了25个人。定居地的重要收入来源——赌场,于去年7月重新开业,并颁布了新的禁烟政策、温度测量和戴口罩以及社交距离要求。

用帕帕基的话来说,这套组合措施是有效的,但并不完美。

虽然定居地亦开始进行疫苗接种,但帕帕基并不知道下一批疫苗何时才能够到来,因此很难制定接种计划。社区的老年人正在急切地盼望进行疫苗接种。

如果我们看一下全美各地土著美国人的形势,梅斯克瓦基族受病毒的影响比其他群体更为严重。当我与帕帕基交谈时,定居地到目前为止有四分之一的部落人口,也就是301人,检测出了新冠阳性,5人因此而死亡。

在定居地之外,塔马郡公共卫生与家庭护理机构的首席执行官夏农·佐夫卡负责领导该地区的疫情应对工作。她一直都居住在这个只有1.7万人的小型农村郡,但去年发生的情况真的是让其大跌眼镜。

佐夫卡在1月初的一个下午对我说:“郡里真的有很大一部分人认为口罩没有什么用。他们认为疫苗是不安全的,而新冠病毒是一场骗局。”

尽管该郡的老人院和肉类加工厂出现了疫情,但对现实的抵制依然存在。事实在于,就新冠病毒的人均死亡率而言,塔马郡在全美所有郡中排前4%。

在德雷科风暴之后,病例亦出现了上升。在居民和塔马郡公共卫生机构无电可用的一周时间中,该郡向居民提供社区餐食,并开放水冷站供居民使用,而这也让病例的跟踪变得尤为复杂。

事情在学年开始时变得尤为糟糕,因为对已知新冠病毒暴露人群而进行的隔离开始影响体育活动。

佐夫卡说:“人们异常愤怒。”她说自己的办公室在尝试调查接触者或通知那些疑似暴露人士时,这些人经常会恶语相加。“人们认为他们有权辱骂你,对你大呼小叫,并进行威胁。”

她很快意识到人们开始采用不同但同样恶意的方式,来应对其办公室的外联工作。

“当密接的定义变为连续15分钟距离某人6英尺之内时,人们很快想出了应对高招。”他们对病例调查员说:“你又没有卷尺或秒表。你怎么知道的。”或者说:“你无法证明当时我们在那里。”

尽管佐夫卡的团队有合作伙伴提供的良好支持,这些合作伙伴来自于学校系统、当地企业、执法机构和梅斯克瓦基族定居地,但来自于社区成员的这种态度让他们的初衷成为了泡影:“我没有想到这么早就会遇到这种情况。我们的想法是‘我们希望保护民众的安全。民众也会希望保护其他民众的安全。’然而在一些限制令解除之后,一旦公共卫生举措真的影响到了其个人生活,事情就变得很棘手。”

有鉴于此,佐夫卡说,我们很难理解州长依然指望艾奥瓦人“会做出正确的抉择”,并借此来控制病毒。

她说,推行口罩令不仅会减缓疾病的传播,同时也应该可以为社区企业提供支持,这些企业曾经尝试鼓励安全行为,但通常遭到反对。

在研究疫情是如何在艾奥瓦州发展时(在我与佐夫卡交谈之前),我偶然间看到了塔马郡公共卫生机构的Facebook页面,并在一定程度上着了迷。

上面的信息十分清晰,而且发布的贴文内容异常透明,该机构会定期更新病例数,并解释为什么会高于州的数据(因为州的数据存在滞后)。

在贴文后面,你还能够感觉到一种不断增强的绝望式恳求:请戴口罩!请洗手!保护你的祖父母!

你只需要读一读评论就可以了解到这个机构所面临的困境。尽管有很多支持和感谢的民众,但评论通常会转变成激烈的争论,主题就是为什么该郡有这么多的病例数。还有人认为整个事件被夸大了。

尽管她的团队尽其所能在自有的Facebook页面上摆出各类事实,但佐夫卡将主要矛头指向了社交媒体,批评它们广为散播有关新冠病毒的误导信息,同时还指责很多媒体讨论病毒时严厉、霸凌的口吻,既包括线上的评论,也包括更多发生在线下的评论。

她预计新冠疫情期间这种情感伤害,以及这种仇恨记忆无法在短时间内消失,而且怀疑论者依然存在。她略感无奈地说:“我觉得那些冥顽不灵的人,只有在被感染后才会相信事实。”

当我与佐夫卡交谈时,她的员工正在进行Moderna疫苗供应数量的管理工作。物流一直都是个难题,尤其是在假日期间,但这次还不错。

她没有大量的时间来思考疫情目前处于哪个阶段,或者过多地去考虑未来。她只是一直在回答有关病毒、疫苗、需要调查的病例的问题,以及所有那些放在其办公桌上的问题。她希望,一旦大量的人接种疫苗后,那么在年底生活就会逐渐恢复正常。

“我在某种程度上认为,与2020年相比,2021年在很多方面没有什么区别。”

当艾奥瓦州的气候学家贾斯汀·格里桑第一次出门调查受德雷科风暴影响的田地时,整个场景令人震惊不已。大片大片的玉米被吹倒,拦腰斩断,或者倾斜得无法进行挽救。其中的一些还受到了冰雹的摧残,破碎不堪,就像是经历了一轮机枪扫射一样。

供职于艾奥瓦州立大学外展和外联部的农田农艺师梅根·安德森说:“站在地里,一眼就能够望到头,然后意识到这是因为玉米全都倒了,实在让人难以接受。”

她哽咽了一会然后说:“我有一份工作,每两周发一次工资。我不会一次性花上数万美元在4月去种植农作物,然后寄希望于9月和10月的收获,然后把钱赚回来。这真的是需要有足够的信念。”

受灾农民不仅仅损失了庄稼,还有大量的基础设施——昂贵的设备、畜棚和谷仓。

安德森说:“需要数年时间才可以缓过来。”

收成和其他保险会承担大部分损失,然而很多人,例如珍妮·波克和斯科特·波克,在2020年依然面临着重大损失,因为他们受到了疫情和德雷科风暴的双重冲击。近些年来,这对住在本顿郡以养牛为生的夫妻眼看着其利润率逐渐降至零点却无能为力。

斯科特说:“我已经从一个纯粹的牛仔变成了一个商人。我们每一天都得精打细算。”

然而,2020年是一种全新的挑战。从去年2月开始,对病毒的恐惧开始让市场感到惊慌,波克夫妇无法获得其以往的出售选择权,以确保能够收回其牲畜的成本。然后,疫情的爆发迫使该州的肉类加工厂关闭。

有鉴于待售牲畜的积压库存,这对夫妇决定修改其牲畜的配给,斯科特说:“基本上会让它们节食60天,以延长其上市的期限。由于牲畜没有保险,我们不得不支付额外的饲料费用。我们当时认为这么做是对的。我们真不知道该怎么办。”

然后德雷科风暴来了。

波克夫妇失去了其畜棚、鸡舍、数英里长的篱笆以及大部分玉米作物,而且有几台拖拉机也报废了。就在他们在德雷科风暴过后,从地下室钻出来的那一刻,他们发现其60只小鸡和下蛋母鸡散落在废墟上。他们的牛也在牧场中自由地走来走去,都还活着。在10月卖牛时,他们连成本都没有赚回来。

总的来说,2020年十分糟糕,然而他们并不打算放弃。

其他人受到的影响更为严重。安德森和其他人担心有可能会出现农场破产潮,而且农业社区可能会出现精神健康问题。(她自己也听到了有一位农民在德雷科风暴过后自杀的消息。)农业巨头嘉吉公司便破产了,该公司曾经赞助艾奥瓦州立大学外展服务机构为农民和家庭提供一些服务。

在艾奥瓦州,并非所有地区的光景都是如此暗淡。对于那些州里已经收割庄稼、而且未遭到德雷科风暴或干旱影响的其他地区居民来说,2020年的收成还不错,而且玉米价格自去年夏季以来也出现了不小的涨幅。

以贸易结算和新冠援助形式发放的联邦救济款为其提供了有力的缓冲,也是农民平均收入在2020年出现增长的主要原因。

与其他地区一样,锡达拉皮兹的灾后恢复依然在继续。大量证据表明,这座城市正在重生,例如一堆堆的废弃砖瓦、破损的栅栏以及铺着油布的屋顶。

然而,人们更多地是对这个社区的重聚而感到异常欣慰,还有一些人依然对城市可以经受这一切而感到吃惊。锡达拉皮兹和马歇尔敦市的市长都称该地区即将有大投资项目进驻,但它们与灾后重建无关,只是可以提升其城市的实力。

自疫情开始以来,艾奥瓦州统计的新冠病例总数达到了321274人,新冠死亡人数4919人。就人均病例数而言,其在全美各州中排名第八,人均死亡率排名第17。(截至本文完稿——编注)

去年11月,艾奥瓦州令人恐怖的抗疫战争给医院带来了巨大的压力,自此之后,形势有了很大的好转:该州的病例数量一直在下滑。有可能是推行口罩令的功劳,亦或是因为艾奥瓦人的责任心。

州长雷诺兹的一名发言人在一份声明中称:“州长在防范新冠疫情方面采取了目标明确、兼顾各方的举措。其目的是保护生命、生计、医院资源以及让孩子能够安全返校。口罩便是一种保护措施,而且州长强调,所有民众几乎每天都应该佩戴。”

对于那些我采访过的人来说,新年几乎不约而同地意味着一种希望,可能是因为疫苗来了,玉米涨价了,社区精神更强大了,或仅仅只是因为2020年的日历终于结束了。

我的父母很好。他们正在思考在光秃秃的院子里种树或通过其他办法来遮阴。他们的脉搏血氧计基本上没有怎么动过,依然躺在盒子里。

在我完成这篇新闻稿时,他们也接种了疫苗。可我仍然在担心他们和疫情,这就是我,也许永远都改不了。

2021年2月5日,在这篇报道发表后,艾奥瓦州的州长金·雷诺兹宣布,从2月7日超级碗周日开始,艾奥瓦州的戴口罩和社交距离要求将被取消。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2021年2月/3月刊,标题为《鹰眼州挽歌》。

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

NIHCM基金会(NIHCM Foundation)为本文的报道慷慨地提供了资助。

天气预报显示有小概率会出现雷雨天气。

在2020年8月10日早间,艾奥瓦州的气象专家贾斯汀·格力桑倒是对这场雨给予了厚望,这里干旱的土地迫切需要饱饮一场雨水。在当天上午与农田农艺师通话时,他还表示自己希望从内布拉斯加远道而来的风暴线亦能光顾艾奥瓦州的上空。

尽管经历了该州历史上最湿润的两个年份,以及去年春天理想的种植条件,但入夏后的这几个月一直温暖多风。到了2020年8月,严重的干旱席卷了艾奥瓦州的中西部地区。

格力桑隶属于艾奥瓦州的农业与土地管理部。在实地考察中,他发现一个有警示意味的迹象,当地的作物出现了生理应激反应:作物开始“燃烧”,其位于底部的叶片开始变得脆黄,也就是植物在自闭生机以节约水分。与此同时,大豆的叶片在日间也翻转了过来,以尽量保留水分。

整个夏天,格力桑看到,并不是没有风暴靠近这个地区,但只要一碰到干燥的空气就会偃旗息鼓。该州的农场极度地渴望雨水的浇灌。

在2018年格力桑成为州气候学家之前,他曾经是艾奥瓦州立大学的一名大气研究科学家,致力于搭建区域气候模型并研究大气的流体动力学。每天,他都会从系统和参数方面来思考大自然母亲的行为。

然而,无论是自己的工作、博士学位还是两个气象学学位,都未能让格力桑为当天突然降临艾奥瓦州的这个自然现象做好准备。

在位于得梅因的家中露台上,他亲眼目睹了风暴的到来。当看到一堵如夜般漆黑的云墙时,他匆忙向地下室跑去,刚跑到一半,一根树枝砸到了他的房子上,扯出了煤气总管,安全警报响起,随即电也停了,时间刚好是上午11点过4秒。

在接下来的两个小时中,格力桑目睹的这场强度和破坏力极强的“巨型”风暴席卷了整个艾奥瓦州。风暴过后,到处都是倒下的大树和电线杆、掀翻的牵引式挂车、扭曲的谷仓、倒伏的作物以及残破的住宅和企业。

美国国家海洋与大气管理局的数据显示,在风暴于艾奥瓦州平息后,也就是其肆虐了14个小时以及770英里的距离之后,造成了约110亿美元的损失,成为了美国历史上破坏力最强的雷暴天气。

在风暴峰值期间,艾奥瓦州当天阵风的风速超过了140英里/小时,这在美国中部地区实属罕见,以至于美国国家航空航天局和格力桑都在研究灾后照片,以弄清楚风暴的起因。

虽然艾奥瓦州到处都是十分留意天气变化的农民,但这场灾难(很多艾奥瓦人依然将其描述为“内陆飓风”)似乎完全没有先例可循,而且不应该出现在这个世界上。

事实上,它是一种德雷科风暴,这个词由艾奥瓦州的首位官方天气观察家盖斯塔乌斯·德特勒夫·亨瑞奇斯杜撰于19世纪80年代。这位脾气不好、十分博学的教授曾经帮助编纂了元素周期表,他认为应该用一个术语来描述艾奥瓦州这种直线型的大风,以区别于旋风(例如龙卷风)。他选择了西班牙术语“德雷科风暴”(意为“直的”)。

如今,德雷科风暴的定义是:波及距离至少240英里,且持续风速超过58英里/小时的风暴。尽管这类风暴在艾奥瓦州大概每两年会发生一次,但该州了解这一术语的人并不多。

即便常驻美国联邦应急管理局堪萨斯城办公室的资深灾害协调员杜维恩·特维斯亦承认自己此前从未听过这个术语。他负责领导该机构在艾奥瓦州的赈灾行动。

当然,龙卷风是这片平原地区常见的灾害,异常恐怖而且破坏力极大。然而,它在其破坏的路径上存在时间短,且范围有限。

德雷科风暴的持续时间更长,而且波及范围更大,这次的风暴更是如此,基本上沿着30号高速公路(也就是老林肯高速公路)和80号州际公路一直向东,在艾奥瓦州的波及宽度达到了90英里,其中包括农场、少数肉类加工城镇、艾奥瓦州两个最大的大学校区(艾姆斯市和艾奥瓦市)以及艾奥瓦州最大的两座城市(得梅因和锡达拉皮兹)。

像格力桑一样,艾奥瓦州人或多或少对这场风暴没有什么准备。德雷科风暴尤为复杂,它属于临时出现的风暴系统,很难提前很长一段时间进行预测。

大多数受灾的艾奥瓦人在当天听到的是标准的8月天气预报,然后开始做自己的事情,没有丝毫信息提示他们只有数个小时的时间去躲避时速达到100英里的大风天气,更不用说在一周多的时间内连生活用电都没有。

本顿郡的第四代农民本·奥尔森当天来到了田间施肥;锡达拉皮兹一家餐馆的老板威利·费尔利正在为其牛排屋采购物资;锡达拉皮兹一家企业的老板史蒂夫·史瑞夫正在与母亲共进午餐;马歇尔敦的一名社会工作人员玛利亚·冈萨雷斯刚刚走出家门遛狗,而她的丈夫则去了银行。

作为本顿郡农村地区五个天主教教区的牧师,神父克雷格·思特梅尔从锡达拉皮兹地区办事归来,这时天空暗了下来。

他在诺威市的家就在圣迈克教堂的旁边。很快,他发现一个垃圾桶从窗前飞过,然后圣迈克教堂34米高、有着140年历史的塔尖空降在了自家院子里。风暴继续肆虐了30分钟,他担心自己的房子会被吹垮。教堂不会也被吹翻吧?

“真是太离谱了。”他说道。

此次风暴是一场悲剧。然而,它的影响远不止如此。

它是各种灾难的大碰撞——席卷美国中部地带的极端天气事件、让经济受到严重冲击的新冠疫情以及去年夏季两党的针锋相对。对很多人来说,他们在德雷科风暴到来之前便已经深陷难以承受的困苦和压力。

对当地的卫生官员来说,控制肆虐的疫情已然让他们抓狂,而风暴的出现则让抗疫任务变得更加复杂。对领导者来说,这场风暴为新冠疫情中社会经济平衡举措又增添了几分重担。

虽然将艾奥瓦州遭受的真实灾害简化为符号有失公允,但在2020年8月10日,有鉴于其被移平的农田、爆炸的谷仓,艾奥瓦州看起来就像是美国毛毡。

提到艾奥瓦州,美国其他地区的人都会联想到平坦、一望无际的玉米地和农场;对于很多白人来说,这是一片只是在飞机上俯瞰过的“飞越之地”。

然而,如今的艾奥瓦州要远比这个老旧的刻板印象复杂的多,也更加多元化。与美国各地一样,艾奥瓦州处于不断的变化之中,而且充满了压力和矛盾。

作为美国玉米、热狗和大豆最大的生产地,艾奥瓦州的经济动力依然来自于农业和相关加工业。然而,随着这些行业削减冗员,艾奥瓦州的增长引擎已经转变为人口更多的市区,支撑行业包括银行、保险、商业服务和医疗保健。

艾奥瓦州有着全美最高的劳动参与率,这个平原州的许多中老年妇女仍然在工作,但其实该州的就业机会并不多,跟不上高技能员工的供应速度。

确实,艾奥瓦州培养的大量人才都流向了外地。艾奥瓦州立大学的经济学家大卫·斯文森说:“艾奥瓦州在教育领域投入了大量的精力。然而,我们的经济却由重负载生产、加工以及农业构成,以至于我们培养了如此多的人才,却没有用武之地。”

在过去10年中,艾奥瓦州的99个郡中有77个郡存在人口流失现象,其中包括众多农村郡,同时也包括城乡结合部的郡,也就是“居住区”,这些都是依赖于制造业的城市,人口在1万至5万之间,而且一直都在削减工作岗位,其当前的城市范围比其经济规模还要大。

这种现象恰好体现了该州不断加深的城乡分化,而且这种分化在该州传统的紫色政治路线中越发明显。

2016年和2020年,艾奥瓦州选择支持了唐纳德·特朗普,但在2020年,支持特朗普的选票更多来自于农村地区。与全美其他地区一样,艾奥瓦州的红色阵营变成了深红,而其蓝色阵营则变成了深蓝。在高层方面则是红色占优:如今,艾奥瓦州的州长、两位参议员以及四名众议员中的三名都是共和党人。

自从进入2020年以来,艾奥瓦州的整体经济没有多少起色。

“基本上处于停滞状态。”斯文森说道。在疫情爆发初期,艾奥瓦州的失业率像美国其他地区一样一路高歌,但自此之后降至3.6%。

斯文森指出,这则消息实际上并没有它表面上看起来的那么美好:艾奥瓦州的就业岗位在去年并没有增加,而是出现了劳动力流失。斯文森怀疑流失的那部分劳动力多数都是需要照看孩子的妇女,或者是因为疫情相关的安全问题而提前退休的员工。

所以可以预见的是,要想知道艾奥瓦州是如何度过2020年,以及该州所有猝不及防的灾难的,不同的地域和不同的询问对象会给你不同的答案。

因此,本文将众多独立的故事融合在一起,而且都与德雷科风暴有关,从西部一直到东部。

它所揭示的画面,尽管在一定程度上为艾奥瓦人所独有,但从根本上来看却是2021年美国大众的写照。它所讲述的这个社会正在尽全力解决一系列复杂、紧密相连的问题,例如新冠疫情和气候变化、动荡的经济与人口、因为政治而极端分化的公众。

由于处在美国版图的正中央,艾奥瓦州自然而然地就像是整个国家的一个缩影。该州所面临的问题,也正是当前美国所面临的核心问题:如何平衡公共卫生与经济的关系?如何平衡个人自由与大众利益之间的关系?如何平衡恐惧和科学与盲目的确信和信仰?

简而言之,艾奥瓦州能够为美国的继续前行提供哪些借鉴?

与众多的百姓一样,我在2020年没少担惊受怕。小题大做一直是我的强项。

因此在去年年初,当知名传染病专家迈克·欧斯特霍尔姆对我说,预计最开始在中国爆发的新冠病毒会像风一样传播时,我立马就想到了我的父母,他们都已经年过七旬,住在锡达拉皮兹,其中还有一个抽了一辈子烟。

我对我的同事说,我担心自己的父母会感染病毒,他们笑了。在艾奥瓦州染病?这是美国最安全的地方。

那时还处于2月的慌乱时期,当时,我们没有想到的是,美国政府竟然耗费了数亿美元将海外美国公民撤回美国。就像这些人可以跑的比病毒还快,且美国国界能够免受感染一样。

新冠疫情也确实侵入了艾奥瓦州。病例最先出现在3月,一群富有探险精神的老年旅行团队在埃及尼罗河的邮轮上感染了病毒。不过,也有可能新冠病毒当时已然在鹰眼州传播开来了。

一开始,艾奥瓦州像美国其他地区一样,对新冠病毒做出了反应,紧急关闭了学校、电影院、教堂、酒吧、室内餐饮店、理发店和日光浴沙龙。

艾奥瓦州的州长金·雷诺兹,一位担任这一职务四年的保守派共和党人,在3月17日宣布该州进入公共卫生紧急状态。然而,她并未下达居家隔离令,而全美像她这样做的州长也没有几位,这也让艾奥瓦州比大多数州显得更加亲商。

我给父母寄去了N95口罩外加脉动血氧计,我要求他们定期使用,并且提出了一个强烈、必然令人反感的建议:他们应该把测得的数据告诉我。(然而他们并没有。)我们每周都会在Zoom上视频,此举在一定程度上让人感到安心。

艾奥瓦州的人口有320万,就人口密度而言在美国排名第35位,并不是特别大。

然而,在疫情最初的几周中,艾奥瓦州出现了令人担忧的病例数量,其中大部分都与肉类加工厂和养老院有关联。那些特定行业的员工和身体虚弱的人成为了新冠病毒的入侵对象。

艾奥瓦州的经济学家斯文森说:“艾奥瓦州在权衡之后的决定是,该州更希望保全经济,而代价便是劳动力的健康和福祉。”

这个浮士德式的交易导致了病毒的区域性传播,也让其他企业成为了牺牲品。

本顿郡的农民本·奥尔森有200头待出栏的牛,准备于3月31日运往附近的泰森公司的工厂。这些牛的价值共计数十万美元,而且耗费了7个月的投资才将其体重从800磅养到了上市恰好所需的重量——1500磅。

他在发运前12个小时接到了电话:工厂爆发了疫情,得再等等。两周后疫情再次爆发,他一个月后以十分糟糕的价格出售了其过重的牛。

艾奥瓦州的养猪户也面临着同样的两难境地。由于猪肉无人问津,一些养猪户不得不对猪实行安乐死。

该州的病例增长曲线直到5月中旬封锁令解除之后才出现平缓迹象,而且形势自此之后变得越发糟糕。

当地媒体和公共医疗界曝光的很多事情,让人们对该州疫情应对举措的信心大减。例如该州的主要检测机构由一家没有经验的犹他州初创企业经营,而且该企业似乎是因为与艾奥瓦州人气明星之子阿什顿·库切尔之间的关系,才获得了这项未经投标的合约。

最重要的是,雷诺兹在一场又一场的新闻发布会上坚决认为,应对疫情的最佳方式就是让艾奥瓦州负责任的人民自行应对。该州无需命令其市民如何去做,因为她信任他们会做出正确的选择。她也不会发布“口罩令”,也不会授权该州的任何市长下达此类命令。

当时,我的父亲依然对秋天去观看艾奥瓦州橄榄球赛抱有很大的希望,然而,他在体育馆置身于一大群无口罩人群中间的景象,成为了当时我最担心的新冠疫情传播场景。

然后,在8月10日的下午,我的母亲群发了一个消息说:“我们十分安全(后面加了一个做祈祷的表情)……”上面有多张照片,差点没有认出来是他们的后院。

“龙卷风?”我妹妹发消息问道。

住址离我父母只有一个街区的弟弟发消息说是“陆地飓风”。

在这之后,电力或信号都断了,也无法再联系。然后在接下来的48小时中,锡达拉皮兹就像是被风从地球上刮走了一样。

社交网站上流传着几段有关这次强风暴的短视频。然而,芝加哥除了提及风灾之外,就再也没有给出更多有关该事件的信息。

锡达拉皮兹并没有从地图上消失,然而,它与其他数百个社区一样,因为风灾而失去了电力。

锡达拉皮兹的整个都市区及其约13.2万人口都因为风灾而断电。(整个艾奥瓦州有68万人口无电可用。)由于信号塔被吹倒,一些人连通信信号都没有。

位于锡达拉皮兹市中心的两家医院中的其中一家——圣卢克医院,在长达51个小时的时间中完全变成了一座孤岛,互联网、电子病例档案、地上通讯线以及所有三家锡达拉皮兹的移动运营商的服务都消失了。与此同时,在风暴和废墟清理过程中受伤的艾奥瓦州东部民众则蜂拥至急救室。风灾过后,前往医院就医的人数是平常的两倍。

锡达拉皮兹UnityPoint医院的总裁兼首席执行官米歇尔·尼尔曼对我说:“这可能是我作为医院管理者所经历的最可怕的时刻。”

评估受灾程度在锡达拉皮兹尤为困难。除了失去电力和通信之外,人们在一开始很难进入这个地区,因为到处都是残砖断瓦和倒塌的大树。(作为“美国树城”,锡达拉皮兹在风暴中估计损失了65%的树木。)

人们很容易将德雷科风暴看作是气候变化所引发的自然伟力的宣泄,特别是锡达拉皮兹这个受灾最严重的城市在前不久才从一次反常的、500年一遇的洪灾中恢复过来。

2008年的这场洪灾摧毁了该市市中心的大部分地区,以及相当一部分经济适用房。

气候学家格里桑对我说,我们很难将单一极端天气事件与气候变化进行关联。然而,有大量不起眼的证据显示,艾奥瓦州的天气正在改变而且增加了德雷科风暴这样破坏性风暴发生的概率。

格里桑的大部分工作是帮助农民应对现实,例如应对更加频繁的大雨。(艾奥瓦州24小时内降雨量超过10厘米的概率,是过去30年中概率的三倍。)

在2020年的艾奥瓦农场和农村生活调查中,81%的农民表示,他们认为气候变化正在发生,较2011年的68%有所增长。而艾奥瓦州普通民众中有67%的人认为全球正在变暖。(这一比例在全美是72%。)

在我父母于黑暗中应对德雷科风暴灾后事宜的那10天中,我与他们交流的机会并不多。在我尝试与他们通话的大多数时间里,他们都曾经抱怨这是在耗费其手机电量,这一点我十分理解,因为他们目前很不容易。我的母亲在谈论朋友、家人和陌生人这些志愿者时,偶尔会感动得掉眼泪,他们会拿着电锯过来帮忙。

我的家人十分幸运,因为倒在屋顶上的树没有造成太大的破坏。我的父母更换了新屋顶,保险公司承担了这笔费用。我的弟弟在今年春天也会更换新的屋顶。

我从他们和锡达拉皮兹的其他人那里感受到,德雷科风暴之后最困难的一件事情就是直面惨痛的损失继续生活,这座满目疮痍的城市仿佛时时刻刻在提醒人们这一年生活的艰辛。我在去年12月到访该城市的时候也切身体会到了这一点。

德雷科风暴所过之处可谓是哀鸿遍野。在得梅因以北48公里的马德里德,风暴掀翻了养老中心Madrid Home这栋四层楼建筑的屋顶,那里有6位新冠患者在顶层接受隔离治疗。

该中心的经营者、Western Home Communities公司的首席执行官克里斯·汉森在参加线上会议时,收到了其马德里德执行总监惊慌失措打来的电话。

汉森的所在地位于马德里德的东北部,距离马德里德有一个小时车程,当时该地区的天空依然晴朗,因此这对汉森来说是一个不可思议的反转。

Western Home在艾奥瓦州有10个养老中心社区,疫情给该公司带来了严峻的考验,其中既有长期护理设施所面临的共性问题(例如缺乏个人防护用品和员工),也有艾奥瓦州独有的问题。

他说:“有几次,我对州长感到十分失望,因为她没有拿出勇气去发布口罩令。”他还表示,自己感觉艾奥瓦州选择了保全经济而不是保护老年人。

“这并非是什么迫不得已的情形,为什么要将所有人置于危险境地?我们的雇员依然待在社区中,他们没得选择。”

在7月底,位于马德里德的Western Home出现第一例新冠病例之前,该公司的经营设施有效地抵御了新冠疫情的爆发。

而该公司的一位医生在公司出诊时将病毒带了进来。在这几天时间中,该中心一楼有6位病人和3名员工被检测出新冠阳性。这对员工的士气来说是个打击。

汉森说:“他们感到十分自责,因为他们觉得自己失败了。”汉森与全美其他医疗和长期护理服务提供商一样,一直在与员工严重短缺问题做斗争。

这个秋季给Western Home带来了巨大损失和恐慌。在公司旗下的一些管理式医疗机构中,有近100%的居民新冠检测呈阳性,而负责照看他们的员工在检测中亦呈阳性。

他对我说:“真的是太恐怖了,我的雇员也有他们的家人。”

最大的挑战在于控制痴呆老人部门的疫情传播。在位于艾奥瓦州克雷斯科市的一所小型养老院中,24位居民里有8位因为新冠肺炎而丧生。他在谈到艾奥瓦州松懈的病毒防范措施时说:“我们亲眼目睹了这类举措的后果。”

当我在今年1月中旬与汉森交谈时,他的员工和居民依然在等待疫苗。

汉森说:“疫苗的推广速度与我们的期望值相距甚远。”他批评的并非是州政府,而是联邦政府,后者正在私营领域的长期护理机构中推广疫苗。

“这并不仅仅是协调不到位的问题。说真的,由于风险迟迟得不到控制,我们之中很快就会有人因此而丧生。”

汉森依然对艾奥瓦州的疫情动态感到十分失望。他注意到,在我们谈论的前一天,数百名不戴口罩的艾奥瓦人汇集在艾奥瓦州议会圆形大厅(州立法人员无需佩戴口罩,而且很多人都没有戴),举行“艾奥瓦州知情选择”集会活动。该集团呼吁终止新冠疫情强制令。

汉森说:“我不知道在整个疫情期间,人们的常识都发生了什么变化?这件事情最终竟然演变成了政治事件,真的让人感到无语。”

在德雷科风暴到来之时,我依然在担心新冠疫情,而且是变得更加担心。艾奥瓦州人会告诉你,灾难会让他们团结一心。然而,这种善意却在助长病毒的传播。

圣卢克医院的尼尔曼说,锡达拉皮兹的新病例的确在德雷科风暴发生之后的恢复过程中略有抬头,但局势倒是没有她此前担心的那么糟糕。

她对我说:“戴口罩的人大幅减少。说实话,人们不得不为了不同层次的需求而工作。”

然而,更糟糕的情形还没有到来。

在去年秋季的大部分时间里,艾奥瓦州的确诊人数在全美新冠疫情图表中一直名列前茅。病毒四处散落,农村郡受到的冲击尤为严重。尽管越来越多的公共卫生部门都在呼吁,但州长雷诺兹依旧只是要求艾奥瓦州民众要负起责任。

随着病例增长曲线的下滑,州长自己与特朗普总统一道出现在演讲台上,没有戴口罩,台下则是得梅因数万名特朗普的支持者。

2020年11月,艾奥瓦州的医疗机构宣布,他们的接纳能力已近饱和,而且缺乏员工或床位来接收更多的新冠患者。

作为应对举措,州长发布了一系列复杂的规定,旨在控制疫情传播:每个孩子在体育比赛中的陪同观众不得超过两名;在室内聚会超过25人,或室外聚会超过100人的场所,必须在面部佩戴覆盖物。

最终,在感恩节之前,雷诺兹以一种乞求原谅的口吻——“没有人愿意这样做……我也不愿意”——发布了全州强制口罩令,只不过附加了一些例外条件。

在马歇尔敦市的市长乔尔·格利尔看来,政府早就应该发布口罩令。格利尔白天还从事律师工作,他看到了其社区自去年早春以来所面临的新冠疫情压力。

马歇尔敦市有2.8万人口,恰好位于艾奥瓦州的中心位置,是一个肉类加工业城市。与其他艾奥瓦州的城市一样,它的猪肉加工厂和最大的雇主JBS很早便出现了疫情。有数十人在去年4月初被检测出阳性,一名当地雇员在5月退休前一周去世。

疫情并未停止蔓延。对格利尔来说,令他感到沮丧和心碎的是,他所在的郡曾经一度是艾奥瓦州受冲击最严重的郡之一,而艾奥瓦州是美国受冲击最严重的州之一。

格利尔会定期与艾奥瓦州中部地区的多名市长召开Zoom会议。很多人都希望发布口罩令,然而,他们并没有权力来做此事。有一些市长则不顾一切地发布了这一命令。

格利尔不愿意越过其法定权力,只是发布了一个市长公告,要求市民覆盖面部,但也警告不得强制执行。而此公告并没有得到市民的重视。

10月,格利尔走进了一家当地酒吧去取外卖订单。酒吧里人群窜动,虽然员工都戴着口罩,但戴口罩的顾客只有他一人。

其他顾客开始嘲讽他的行为,并说他不像个男人。

格利尔告诉我说:“这些人的科学考试肯定不及格,无法跟他们讲道理。”

马歇尔敦市的服务生便成为了配戴口罩分歧的牺牲品。

La Carreta Mexican Grill餐厅的老板、31岁的阿尔方索·梅迪纳在11月的最后一周便染上了新冠病毒。这家餐厅是该城市颇有人气的美墨边境菜餐厅。他失去了味觉和嗅觉,他估计,在去年那个时候,其餐厅的17名服务生中有百分之八九十都已经出现了这一症状。

自去年3月以来,他的团队在餐厅尝试了保持社交距离,并采取了预防措施。他们佩戴了口罩,但顾客几乎都没有戴口罩。

梅迪纳在1月初对我说:“客户无需戴口罩,但病毒基本上就是这么传播的,真的很令人沮丧。所有人本来应该都戴口罩,但我们知道感染病毒只是迟早的事情。”

尽管马歇尔敦市的多家大型卖场,例如Menards和沃尔玛在疫情初期便开始要求覆盖面部,然而由于没有州强制令,同时作为一家少数族裔持有的企业,梅迪纳认为在La Carreta餐馆很难强制推行佩戴口罩的政策。

他的雇员,尤其是那些兼职工作的高中生,在与顾客打交道时也心怀感染病毒的恐惧。他希望顾客可以担负起责任。

“如果你来这里吃饭,是因为这是你最喜爱的餐馆,那么为什么不能佩戴口罩?”(他说,自从州长发布全州强制令之后,几乎所有人都会佩戴口罩。)

梅迪纳祈祷其员工千万不要一次性全部染病,如果是这样的话,他就得闭店。餐馆在疫情期间的生意非常不错,他将这一业绩归功于酒品外卖销售。

事实上,La Carreta餐馆在2020年的五月五日节那天是有史以来生意最好的节日。

梅迪纳称自己十分幸运,因为他是在生意平平的感恩节感染了病毒,当时,就算他10天不去,也不会对店里的生意有什么影响。

他的大多数雇员都出现过像他这样轻微的症状,而且所有人最终都康复了,然而其团队中几乎每一个人,都有相熟之人死于新冠疫情:梅迪纳在俄亥俄州52岁的叔叔;在墨西哥给梅迪纳父母看病的30岁医生;店里大厨的父亲;两位服务生的祖父;店里的老顾客。

他说:“死神一直都在我们周围。”

梅迪纳出生于弗吉尼亚州的罗阿诺克市,他小时候一直跟随父母(墨西哥移民)辗转于美国各地,并于这一期间开设了多家蒸蒸日上的美国墨西哥边境菜餐厅。

他5岁时来到了艾奥瓦州,不久后搬到了马歇尔敦市。他十分喜欢这里的多元化氛围、自己所接受的良好教育以及大众的友善。

他说:“这是一个适合成长的地方。你知道的,‘艾奥瓦的友好’,你真的能够体验到这一点。”

在疫情爆发之后,梅迪纳注意到他的批发商可以供应众多高需求物品,例如洗手液、大米和豆子、厕纸等。他下了一大批订单,而后开始在当地转售。

他曾经一度向当地养老院提供手套。在整个疫情期间,他向当地的食品募捐活动捐赠了主要原料,并为失去家庭成员的家庭组织了募捐活动。

然而,梅迪纳最出名可能还是那句“没有爱就没有玉米卷”口号,这是今秋他在餐厅门前的告示牌,以及商品上写下的宣传语。

在乔治·弗洛伊德和其他非武装黑人公民在去年夏天遭到警察杀害之后,梅迪纳觉得有责任通过其平台来宣传其作为当地企业主的价值观。他在社交媒体上进行了试验,得到了不错的反响,因此他在自家餐厅La Carreta前放了一块牌子。这块牌子上面写着一些在他看来无可指责的常识性箴言:“黑人的命也是命”、“人权就是妇女的权益”、“科学是真实存在的”。

然而有一天,一位顾客在看到这些标语后,在收据上写下了愤怒的留言,称这些标语不符合基督教义。

梅迪纳在其个人的Facebook页面公布了这张收据的照片,并留言说:“没有爱就没有玉米卷。”

他还创建了打着该标语的网站和在线服装店,呼吁公平和平等,而且建议将总统大选日改为联邦假日,以确保所有人都能够投票。网站所获利润则捐给了梅迪纳此前设立的当地奖学金基金。

他的信息被疯狂转载,尤其是他在去年10月的总统大选预备阶段接受了CNN的专访之后更是如此。对“没有爱就没有玉米卷”帽子和衬衫的订单从全世界蜂拥而至,而且随着人们在11月发布自己的投票照片,很多人都@他们,“#没有爱就没有玉米卷”。他用这笔钱在马歇尔敦市的社区大学设立了14项奖学金。

梅迪纳表示,他也曾经收到过批评信件,而且不只一封,上面的措辞要比促使他发起这一切的收据留言更加激烈。

我问他,新冠疫情和当前的政治气候是否会让艾奥瓦州没有以前那么友好了?他称,自己和雇员在餐厅从来不谈论政治,这是有原因的。

他说:“马歇尔敦市里有些人有着与其他人迥异的观点,而且我尊重每个人的观点。相比我自己,这里的一些客户有着不同的政党背景。我对我的雇员说,不管来店客人拿着什么工具,或其衬衫写着什么内容,‘我们都应该一视同仁地提供五星级服务。’”

市长格利尔发现,自己越发难以保持中立立场。他哀叹到,其城市的疫情已经沦为了一种政治工具。他曾经因为新冠疫情而受到责备,其中涉及电子邮件、短信以及在其市长Facebook页面下的众多留言。

他说:“有一半人对学校开学感到异常愤怒,而另一半则对不开学十分恼火。场面真的很难看。”

格利尔已经上任三年,在这期间,他已经应对了马歇尔敦市一场又一场的灾难。2018年7月的一天,一场龙卷风直接从大街刮过,吹倒了当地政府的钟楼,让历史古迹和市中心企业一片狼藉,随后又摧毁了马歇尔敦市低收入地区数座房屋。这也让德雷科风暴在某种程度上成为了异常残酷的超自然现象。

应对这些灾难的诸多重担落到了金伯利·埃尔德的肩上,她是马歇尔郡的应急管理协调员。她自2003年以来便一直担任这一职务。

然而,灾害似乎一年比一年多,可以用来赈灾的物资却越来越少。

在2020年的大部分时间中,她在办公室之外工作时总是拿着很多盒子。其中一些盒子里装着个人防护用品,她自己会将郡里的库存送到养老院和应急响应员的手中。其他盒子则是文件盒,里面全是文件,也就是灾害过后大量的行政管理工作。

埃尔德两年多以来都没有休过假,而且作为一个只有一名员工的部门,她最害怕自己感染新冠病毒。埃尔德说:“如果我像其他人一样住院了,那他们该怎么办?”

埃尔德并非是唯一一位在恢复过程中陷入困境的人士。

为了从保险公司和州机构获得及时的救援,社区里的某些人付出了更多的努力。与艾奥瓦州其他城市一样,马歇尔敦市尤为多元化。最近的人口调查显示,其30%的人口是西班牙裔人。马歇尔敦市学校区域的学生能够讲40多种语言;幼儿园中的儿童有70%都是非白人族群。

肉类加工工厂进一步助长了这种多元文化主义,因为长期以来,这里的工作吸引了各类人口的到来,包括最近的缅甸和刚果难民。

在引导恢复的进程中,语言障碍是一个问题,另一个问题则是时间。城市的移民人口占马歇尔敦市必要劳动力的很大一部分,这些人所从事的工作通常没有什么灵活性可言,他们连排队等保险理算员的时间都没有。

对于那些梅斯克瓦基族定居地(艾奥瓦州塔马郡占地8000英亩的地界,位于马歇尔敦市的东部,居住着密西西比Sac & Fox部落)的民众来说,因为德雷科风暴而导致的搬迁带来了另一个惨痛的成本:新冠疫情。

作为艾奥瓦州唯一受到联邦政府承认的部落,梅斯克瓦基族于1857年购买了这块土地,他们在此之前曾经反对联邦政府将其流放至堪萨斯城保护区的决定。

多年来,部落拓展了其占有的财产以及定居地,目前居住着约1200名部落成员,拥有其自己的医疗诊所、法院和学校。1992年,梅斯克瓦基族在地界上开设了一家酒店和赌场,并打出了拥有“艾奥瓦州最不牢靠的老虎机”的广告。如今,部落运营70%的资金来自于这座赌场。

定居地共有350处住所,其中271座毁于德雷科风暴,而且风暴过后,拥有发电机的酒店自然也就成为了受影响人群的避难所。

定居地的执行总监劳伦斯·斯波提伯德称,700名部落成员将酒店挤得水泄不通,有的房间甚至住着5至6人。人们发现,过去数月期间与自己保持着社交距离的人,如今就挨着自己。

斯波提伯德说:“人们的互动变得更加紧密,而且也合作的更紧密。为了实现这一点,我们不得不撤离了安保。结果,病例出现了激增。”

定居地在某种程度上与艾奥瓦州的疫情应对举措可谓是背道而驰。

梅斯克瓦基部落医疗诊所的卫生总监卢迪·帕帕基于去年3月发现了该社区的首例新冠病例。一名部落成员因为呼吸问题而上医院就诊,后来在病毒检测中呈阳性。

很快,这位人士的家庭成员及其密接也感染了病毒。有几个病例属于重症,需要住院,有一名老人因为病毒感染而去世。

帕帕基说:“一开始,我们只是一个不大的‘震中’。”他知道这里有很多人都十分脆弱,有些是老年人,有些人存在有健康问题,例如糖尿病和高血压等,因此这群人有着更大的风险。

部落领袖几乎立即做出响应,下达了居家隔离令,关闭了定居地的赌场和其他经营设施。他们继续向雇员支付薪资,并要求他们待在家中。得益于印第安人健康服务,部落成员拥有稳健、可获取的检测基础设施。

当部落在去年夏初再次开放时,其方式异常保守:部落要求公众佩戴口罩,并取消了年度的祈祷仪式以及其他具有重要文化意义的仪式性聚会。

然而这一举措也存在局限性。很多定居地的居民都在塔马、托雷多和马歇尔敦市等附近城市工作,而且所有人都得离开定居地购买百货和其他物资。梅斯克瓦基族切断病毒传播举措的效果,不大可能超过这些周边社区。

斯波提伯德说:“美国有些州对疫情不怎么重视,艾奥瓦州便是其中之一。因此,安保有点无精打采、散漫,而且人们通常不会长时间地戴口罩。”为了工作,斯波提伯德在去年5月从西雅图搬到了这里(他并非是部落成员)。

与众多艾奥瓦州的医疗专业人士一样,帕帕基对雷诺兹州长的疫情应对举措感到非常失望。他会收听州长有关疫情的新闻发布会,但每次都感到沮丧不已,因为州长总是一成不变地坚持认为,她相信艾奥瓦人可以做出正确的抉择。

他说:“很明显,艾奥瓦人做不到,因为我们的病例数在继续飙升。”

他承认,定居地存在一些类似的挑战,社区里也有一些人对于戴口罩令以及如何开展其社交生活的要求十分抵制。

在定居地的一个圣诞集会上,一名感染者传染了25个人。定居地的重要收入来源——赌场,于去年7月重新开业,并颁布了新的禁烟政策、温度测量和戴口罩以及社交距离要求。

用帕帕基的话来说,这套组合措施是有效的,但并不完美。

虽然定居地亦开始进行疫苗接种,但帕帕基并不知道下一批疫苗何时才能够到来,因此很难制定接种计划。社区的老年人正在急切地盼望进行疫苗接种。

如果我们看一下全美各地土著美国人的形势,梅斯克瓦基族受病毒的影响比其他群体更为严重。当我与帕帕基交谈时,定居地到目前为止有四分之一的部落人口,也就是301人,检测出了新冠阳性,5人因此而死亡。

在定居地之外,塔马郡公共卫生与家庭护理机构的首席执行官夏农·佐夫卡负责领导该地区的疫情应对工作。她一直都居住在这个只有1.7万人的小型农村郡,但去年发生的情况真的是让其大跌眼镜。

佐夫卡在1月初的一个下午对我说:“郡里真的有很大一部分人认为口罩没有什么用。他们认为疫苗是不安全的,而新冠病毒是一场骗局。”

尽管该郡的老人院和肉类加工厂出现了疫情,但对现实的抵制依然存在。事实在于,就新冠病毒的人均死亡率而言,塔马郡在全美所有郡中排前4%。

在德雷科风暴之后,病例亦出现了上升。在居民和塔马郡公共卫生机构无电可用的一周时间中,该郡向居民提供社区餐食,并开放水冷站供居民使用,而这也让病例的跟踪变得尤为复杂。

事情在学年开始时变得尤为糟糕,因为对已知新冠病毒暴露人群而进行的隔离开始影响体育活动。

佐夫卡说:“人们异常愤怒。”她说自己的办公室在尝试调查接触者或通知那些疑似暴露人士时,这些人经常会恶语相加。“人们认为他们有权辱骂你,对你大呼小叫,并进行威胁。”

她很快意识到人们开始采用不同但同样恶意的方式,来应对其办公室的外联工作。

“当密接的定义变为连续15分钟距离某人6英尺之内时,人们很快想出了应对高招。”他们对病例调查员说:“你又没有卷尺或秒表。你怎么知道的。”或者说:“你无法证明当时我们在那里。”

尽管佐夫卡的团队有合作伙伴提供的良好支持,这些合作伙伴来自于学校系统、当地企业、执法机构和梅斯克瓦基族定居地,但来自于社区成员的这种态度让他们的初衷成为了泡影:“我没有想到这么早就会遇到这种情况。我们的想法是‘我们希望保护民众的安全。民众也会希望保护其他民众的安全。’然而在一些限制令解除之后,一旦公共卫生举措真的影响到了其个人生活,事情就变得很棘手。”

有鉴于此,佐夫卡说,我们很难理解州长依然指望艾奥瓦人“会做出正确的抉择”,并借此来控制病毒。

她说,推行口罩令不仅会减缓疾病的传播,同时也应该可以为社区企业提供支持,这些企业曾经尝试鼓励安全行为,但通常遭到反对。

在研究疫情是如何在艾奥瓦州发展时(在我与佐夫卡交谈之前),我偶然间看到了塔马郡公共卫生机构的Facebook页面,并在一定程度上着了迷。

上面的信息十分清晰,而且发布的贴文内容异常透明,该机构会定期更新病例数,并解释为什么会高于州的数据(因为州的数据存在滞后)。

在贴文后面,你还能够感觉到一种不断增强的绝望式恳求:请戴口罩!请洗手!保护你的祖父母!

你只需要读一读评论就可以了解到这个机构所面临的困境。尽管有很多支持和感谢的民众,但评论通常会转变成激烈的争论,主题就是为什么该郡有这么多的病例数。还有人认为整个事件被夸大了。

尽管她的团队尽其所能在自有的Facebook页面上摆出各类事实,但佐夫卡将主要矛头指向了社交媒体,批评它们广为散播有关新冠病毒的误导信息,同时还指责很多媒体讨论病毒时严厉、霸凌的口吻,既包括线上的评论,也包括更多发生在线下的评论。

她预计新冠疫情期间这种情感伤害,以及这种仇恨记忆无法在短时间内消失,而且怀疑论者依然存在。她略感无奈地说:“我觉得那些冥顽不灵的人,只有在被感染后才会相信事实。”

当我与佐夫卡交谈时,她的员工正在进行Moderna疫苗供应数量的管理工作。物流一直都是个难题,尤其是在假日期间,但这次还不错。

她没有大量的时间来思考疫情目前处于哪个阶段,或者过多地去考虑未来。她只是一直在回答有关病毒、疫苗、需要调查的病例的问题,以及所有那些放在其办公桌上的问题。她希望,一旦大量的人接种疫苗后,那么在年底生活就会逐渐恢复正常。

“我在某种程度上认为,与2020年相比,2021年在很多方面没有什么区别。”

当艾奥瓦州的气候学家贾斯汀·格里桑第一次出门调查受德雷科风暴影响的田地时,整个场景令人震惊不已。大片大片的玉米被吹倒,拦腰斩断,或者倾斜得无法进行挽救。其中的一些还受到了冰雹的摧残,破碎不堪,就像是经历了一轮机枪扫射一样。

供职于艾奥瓦州立大学外展和外联部的农田农艺师梅根·安德森说:“站在地里,一眼就能够望到头,然后意识到这是因为玉米全都倒了,实在让人难以接受。”

她哽咽了一会然后说:“我有一份工作,每两周发一次工资。我不会一次性花上数万美元在4月去种植农作物,然后寄希望于9月和10月的收获,然后把钱赚回来。这真的是需要有足够的信念。”

受灾农民不仅仅损失了庄稼,还有大量的基础设施——昂贵的设备、畜棚和谷仓。

安德森说:“需要数年时间才可以缓过来。”

收成和其他保险会承担大部分损失,然而很多人,例如珍妮·波克和斯科特·波克,在2020年依然面临着重大损失,因为他们受到了疫情和德雷科风暴的双重冲击。近些年来,这对住在本顿郡以养牛为生的夫妻眼看着其利润率逐渐降至零点却无能为力。

斯科特说:“我已经从一个纯粹的牛仔变成了一个商人。我们每一天都得精打细算。”

然而,2020年是一种全新的挑战。从去年2月开始,对病毒的恐惧开始让市场感到惊慌,波克夫妇无法获得其以往的出售选择权,以确保能够收回其牲畜的成本。然后,疫情的爆发迫使该州的肉类加工厂关闭。

有鉴于待售牲畜的积压库存,这对夫妇决定修改其牲畜的配给,斯科特说:“基本上会让它们节食60天,以延长其上市的期限。由于牲畜没有保险,我们不得不支付额外的饲料费用。我们当时认为这么做是对的。我们真不知道该怎么办。”

然后德雷科风暴来了。

波克夫妇失去了其畜棚、鸡舍、数英里长的篱笆以及大部分玉米作物,而且有几台拖拉机也报废了。就在他们在德雷科风暴过后,从地下室钻出来的那一刻,他们发现其60只小鸡和下蛋母鸡散落在废墟上。他们的牛也在牧场中自由地走来走去,都还活着。在10月卖牛时,他们连成本都没有赚回来。

总的来说,2020年十分糟糕,然而他们并不打算放弃。

其他人受到的影响更为严重。安德森和其他人担心有可能会出现农场破产潮,而且农业社区可能会出现精神健康问题。(她自己也听到了有一位农民在德雷科风暴过后自杀的消息。)农业巨头嘉吉公司便破产了,该公司曾经赞助艾奥瓦州立大学外展服务机构为农民和家庭提供一些服务。

在艾奥瓦州,并非所有地区的光景都是如此暗淡。对于那些州里已经收割庄稼、而且未遭到德雷科风暴或干旱影响的其他地区居民来说,2020年的收成还不错,而且玉米价格自去年夏季以来也出现了不小的涨幅。

以贸易结算和新冠援助形式发放的联邦救济款为其提供了有力的缓冲,也是农民平均收入在2020年出现增长的主要原因。

与其他地区一样,锡达拉皮兹的灾后恢复依然在继续。大量证据表明,这座城市正在重生,例如一堆堆的废弃砖瓦、破损的栅栏以及铺着油布的屋顶。

然而,人们更多地是对这个社区的重聚而感到异常欣慰,还有一些人依然对城市可以经受这一切而感到吃惊。锡达拉皮兹和马歇尔敦市的市长都称该地区即将有大投资项目进驻,但它们与灾后重建无关,只是可以提升其城市的实力。

自疫情开始以来,艾奥瓦州统计的新冠病例总数达到了321274人,新冠死亡人数4919人。就人均病例数而言,其在全美各州中排名第八,人均死亡率排名第17。(截至本文完稿——编注)

去年11月,艾奥瓦州令人恐怖的抗疫战争给医院带来了巨大的压力,自此之后,形势有了很大的好转:该州的病例数量一直在下滑。有可能是推行口罩令的功劳,亦或是因为艾奥瓦人的责任心。

州长雷诺兹的一名发言人在一份声明中称:“州长在防范新冠疫情方面采取了目标明确、兼顾各方的举措。其目的是保护生命、生计、医院资源以及让孩子能够安全返校。口罩便是一种保护措施,而且州长强调,所有民众几乎每天都应该佩戴。”

对于那些我采访过的人来说,新年几乎不约而同地意味着一种希望,可能是因为疫苗来了,玉米涨价了,社区精神更强大了,或仅仅只是因为2020年的日历终于结束了。

我的父母很好。他们正在思考在光秃秃的院子里种树或通过其他办法来遮阴。他们的脉搏血氧计基本上没有怎么动过,依然躺在盒子里。

在我完成这篇新闻稿时,他们也接种了疫苗。可我仍然在担心他们和疫情,这就是我,也许永远都改不了。

2021年2月5日,在这篇报道发表后,艾奥瓦州的州长金·雷诺兹宣布,从2月7日超级碗周日开始,艾奥瓦州的戴口罩和社交距离要求将被取消。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2021年2月/3月刊,标题为《鹰眼州挽歌》。

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

A grant from the NIHCM Foundation generously helped fund reporting for this story.

The weather report showed a slight risk of thunderstorms, and in the early hours of Aug. 10, Justin Glisan, Iowa’s state climatologist, was feeling hopeful about that. The land was dry and crying out for a good soak. On a call with field agronomists that morning, he’d exchanged wishes that the storm line making its way across Nebraska would hold together over Iowa.

Despite coming off two of the state’s wettest years on record and ideal planting conditions in the spring, the summer months had been warm and windy, and by August, severe drought had taken hold in West Central Iowa. Glisan is attached to Iowa’s Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship, and on field visits, he had observed the telltale signs that crops were experiencing physiological stress: The corn had started to “fire,” its lower leaves turning a brittle yellow as the plant shut down to conserve water; the leaves of soybeans, meanwhile, were flipping during the day to keep in what moisture they could.

All summer long, Glisan had watched storms approach the region, and just fizzle out as they hit dry air. The state’s farmland desperately needed rain.

Before he became state climatologist in 2018, Glisan worked as a research atmospheric scientist at Iowa State University, building regional climate models and studying the fluid dynamics of the atmosphere. Every day, he thought about the acts of Mother Nature in terms of systems and parameters.

But nothing—not that work, not his Ph.D. and two meteorology degrees, nor his storm-chasing experience in the Midwest—prepared him for what so suddenly materialized over Iowa that day. He saw it coming from the deck of his Des Moines home, a wall of dark-as-night clouds that sent him scuttling to his basement. He was only halfway there when a tree limb hit his house and ripped out a gas main. The security alarm went off the moment he lost power—precisely four seconds past 11 a.m.

Over the course of the next two hours, the “monster” storm Glisan witnessed ripped across the state of Iowa with increasing intensity and devastation, leaving in its wake felled trees, downed power lines, overturned semis, crumpled grain bins, flattened crops, and mangled homes and businesses. By the time the storm petered out in Ohio, at the end of its 14-hour, 770-mile run, it had caused some $11 billion in damage, making it the most costly thunderstorm in American history, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). At its peak, the wind gusts that day are thought to have exceeded 140 miles per hour in Iowa, such an anomaly in the middle of the country that NASA and Glisan are studying photos of damage to make sense of the storm.

Even in a state full of weather-conscious farmers, the event—which many Iowans still describe as an “inland hurricane”—seemed completely alien and unworldly, like nothing they’d seen before. In fact, it was a derecho (pronounced deh-REY-cho), a term coined in the 1880s by Iowa’s first official weather observer, Gustavus Detlef Hinrichs. A cantankerous, polymathic professor who had a hand in developing the periodic table, Hinrichs believed there should be a term to distinguish Iowa’s straight-line wind events from rotational ones (a.k.a., tornadoes). He settled on the Spanish term “derecho” (meaning “straight”), which is defined today as a windstorm that travels at least 240 miles with sustained winds over 58 mph. Though such storms occur about every two years in Iowa, the term was not widely known in the state. Even DuWayne Tewes, the veteran disaster coordinator based in FEMA’s Kansas City office who led the agency’s response in Iowa, conceded he’d never heard the term before.

Tornadoes are of course the common disaster of the plains—terrifying and devastating, but short-lived and limited in their path of destruction. Derechos tend to be longer and more sweeping affairs, and this one was especially so. The storm essentially traveled due east along Highway 30—the old Lincoln Highway—and Interstate 80, cutting a swath of the state 90 miles wide that includes valuable farmland, a handful of meatpacking towns, Iowa’s two largest university campuses (Ames and Iowa City), and Iowa’s two largest cities (Des Moines and Cedar Rapids).

They were all caught, like Glisan, more or less unprepared. Derechos are especially complex, impromptu storm systems, making them hard to forecast with much lead time. Most impacted Iowans started their day with a standard August weather report and went about their activities, with no inkling that they’d have to shelter from 100 mph winds in a few hours, let alone live a week or more without power.

Ben Olson, a fourth-generation farmer in Benton County, was out hauling manure; Willie Fairley, a Cedar Rapids restaurateur was picking up supplies for his rib shack; Steve Shriver, a Cedar Rapids business owner, was grabbing lunch with his mom; Maria Gonzalez, a social worker in Marshalltown had just gone out with her dog, and her husband had run to the bank.

Father Craig Steimel, the pastor at five Catholic parishes in rural Benton Country, returned from running errands in the Cedar Rapids area just as the sky turned dark. His home in Norway is adjacent to St. Michael’s Church, and the next thing he knew a garbage can flew by his window and then St. Michael’s 110-foot, 140-year-old steeple landed in his yard. As the storm raged for another 30 minutes, he wondered if his house would collapse. Would the church blow over? “It was just ungodly,” he says.

The storm was a trauma. But it was also more than that. It was a collision of disasters—this extreme weather event hit America’s heartland in the middle of an economy-bruising pandemic and a summer of bitter polarization. For many, the derecho layered on more hardship and stress when they could least afford it. For local health officials, the storm complicated the already challenging task of managing a raging virus. For leaders, it piled another few Jenga pieces on the COVID-19 socioeconomic balancing act.

It’s not fair to reduce Iowa’s very real disasters to symbol, but on Aug. 10, with its flattened fields and exploded barns, Iowa looked like America felt.

*****

When the rest of the country thinks of Iowa, they almost certainly conjure up long, flat stretches of cornfields and farms; flyover country populated almost exclusively by white people. But the state today is far more complex and diverse than the old stereotype suggests—like anywhere in America, it’s a place in flux, full of tensions and contradictions.

One of the nation’s top producers of corn, hogs, and soybeans, Iowa’s economy remains driven by agriculture and related manufacturing. But as those industries have shed labor, Iowa’s growth has shifted to more populated urban areas, powered by sectors like banking, insurance, business services, and health care.

Iowa has one of the nation’s highest labor participation rates—it’s a quirk of the Plains states that many middle-aged and older women work—but there aren’t enough job opportunities to match the number of highly skilled workers the state supplies. Indeed, Iowa exports a lot of the talent it develops. “We educate the hell out of Iowans,” says Dave Swenson, an economist with Iowa State University. “But the way our economy is configured with its heavy loading, production, manufacturing, and agriculture—all of that talent we educate, we can’t use it.”

Over the past decade, 70 of Iowa’s 99 counties lost population. That includes many rural counties but also—and more troubling, says Swenson—the semi-urban ones that are home to “micropolitans,” the manufacturing-dependent cities of 10,000 to 50,000 that have been shedding jobs and now have physical footprints larger than their economies. It’s a dynamic that plays into the state’s deepening urban and rural divide, which has been increasingly visible in the traditionally purple state’s politics. In 2016 and 2020, Iowa supported Trump, but in 2020, more of that vote was in rural parts of the state. As is the case across the country, Iowa’s red communities have gotten redder, and its blue communities bluer. At a high level, red is winning: Today, Iowa’s governor, both of its senators, and three of its four representatives in Congress are Republican.

Going into 2020, Iowa’s overall economy was flat. “It wasn’t growing at all,” says Swenson. Unemployment spiked like it did everywhere at the start of the pandemic but has since fallen to 3.6%. Swenson says that’s less good news than it appears: Iowa didn’t gain jobs during the year, it lost workforce. Swenson suspects the dropouts are largely women shouldering childcare responsibilities or people who retired early for pandemic-related safety concerns.

Not surprisingly, how Iowans weathered the past year and all of its unanticipated catastrophes depends on where you look and whom you ask. And so this accounting is a mosaic of many different individual stories, told as the derecho blew, from west to east.

The picture it reveals, while distinctly Iowan in some ways, is one that, from a distance, looks fundamentally American in 2021. It reveals a society struggling to grapple with a series of complex, interlocking issues at once—a novel coronavirus and climate change; an economy and demography in flux; a public bitterly polarized by politics. Sitting as it does in the geographic middle of the U.S., Iowa functions naturally as a microcosm of the broader nation. And the questions it’s wrestling with echo those at the heart of our current circumstances: How do you balance public health and the economy? Personal freedom and the greater good? Fear and science with blind certainty and belief?

In short, what can Iowa show us about our way forward?

*****

Like many people, I spent a lot of 2020 worrying. Catastrophizing is something I’ve always been good at, and so early last year, when the esteemed infectious disease expert Michael Osterholm told me that he expected a novel coronavirus in China to spread like the wind, my mind instantly went to my parents, both of whom are in their seventies and one a lifelong smoker, in Cedar Rapids.

When I told my colleagues I was worried about my parents getting the virus, they chuckled. In Iowa? That’s the safest place you could be. This was the frenzied month of February when we lacked such imagination that the U.S. government was spending millions to evacuate American citizens from foreign countries, as if one could outrun the virus and that U.S. borders would protect them.

The coronavirus did of course reach Iowa. The first known cases were in early March—an adventurous group of senior travelers had contracted it in Egypt while on a Nile cruise—though it was probably spreading in the Hawkeye State already.

In the beginning, Iowa reacted to the coronavirus like much of the country, with the abrupt closure of schools, theaters, churches, bars, indoor dining, barbers, and tanning salons. Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds, a conservative Republican in her fourth year on the job, issued a state public health emergency because of the virus on March 17. But she did not issue a shelter-in-place order, one of the few governors to not do so, leaving Iowa more open for business than most states.

I sent my parents N95 masks as well as a pulse oximeter, which I asked them to use regularly with the strong, and surely annoying, suggestion that they report their readings back to me. (They didn’t.) We did weekly Zooms, which lifted spirits and provided some peace of mind.

Iowa, with a population of 3.2 million, is not a particularly dense state—it ranks 35th in the U.S. in density. But in the early weeks of the pandemic, the state had an alarming number of cases, most of them linked to meatpacking plants and nursing homes. The virus was hitting the essential and the infirm. “The tradeoff in Iowa was we were more than willing to maintain our economy, at the expense of the health and well-being of our workforce,” says Swenson, the Iowa State economist.

That Faustian deal led to community spread and punished other businesses too. Ben Olson, the farmer in Benton County, had 200 beef cattle lined up, ready for delivery at a nearby Tyson plant on March 31. Together they represented hundreds of thousands of dollars and the seven-month investment in raising them from 800 pounds to their precisely desired sale weight—1,500 pounds. He got a call 12 hours before go time: There was an outbreak at the plant; he’d have to wait. The same thing happened two weeks later. He sold his oversize cattle a month late, for a bad price. Pig farmers across the state faced similar dilemmas; some, with no market for their hogs, had to euthanize them.

The state’s curve hadn’t flattened much before Iowa reopened in mid-May, and since then the picture has gotten much, much worse. There were plenty of things, brought to light by local media and the public health community, that did not inspire great confidence in the state’s response—like, for instance, the fact that the state’s main testing infrastructure was provided by an inexperienced Utah startup that won a no-bid contract seemingly due to its connections to Ashton Kutcher, Iowa’s favorite celebrity son.

Most of all, Reynolds was absolutely insistent, press conference after press conference, that the best approach to the pandemic was to put it in Iowans’ responsible hands. The state didn’t need to order its citizens about what to do because she trusted them to do the right thing. She wouldn’t issue a mask mandate, nor would she give mayors in her state the power to do so.

At the time, my father was still holding out hope that there would be Iowa football games to attend in the fall, and the prospect of him in a stadium with the mask-less masses was among my worst COVID fears at the time.

Then, in the middle of the afternoon on Aug. 10, my mom sent a group text that began, “We are safe [prayer hands emoji] …” There was a series of photos that were barely recognizable as their backyard. “Tornado!?” My sister texted. My brother, who lives a block away from my parents, wrote “land hurricane.” They didn’t have the power or cell reception to communicate much beyond that, and for the next 48 hours it was as if Cedar Rapids had been blown off the face of the earth.

There were a few video clips of the intense storm circulating on social media, but it was hard to find much news on what had happened beyond mention of a wind event in Chicago. Cedar Rapids hadn’t been blown off the map exactly, but it, along with hundreds of other communities, had blown off the grid.

All of the Cedar Rapids metropolitan area, some 132,000 people, lost power in the storm. (Across the state, 680,000 customers did.) With cell towers toppled, some lost communications too. For a 51-hour period, St. Luke’s Hospital, one of two medical centers in downtown Cedar Rapids, was a complete island—losing Internet, electronic medical records, the landline, and service from all three of Cedar Rapids’ cell carriers. At the same time, Eastern Iowans who had been injured in the storm or debris-cleaning efforts were pouring into the emergency room. The hospital saw twice its normal volume in the 24 hours after the derecho. “It was probably the scariest time I’ve had as a hospital administrator,” the hospital’s President and CEO, Michelle Niermann of UnityPoint Cedar Rapids, tells me.

Assessing the scope of the damage was especially challenging in Cedar Rapids, which—beyond the loss of power and communications—was initially almost untraversable because of all the debris and fallen trees. (As a “Tree City USA,” Cedar Rapids a lost an estimated 65% of its canopy in the storm.)

It’s hard not to think of the derecho as a blatant spectacle of climate change, particularly when the city it hit hardest, Cedar Rapids, is not long recovered from the freak 500-year flood that destroyed much of its downtown and a good chunk of its affordable housing in 2008.

As climatologist Glisan told me, it’s difficult to link a single extreme weather event to climate change. But there’s plenty of subtle evidence that Iowa’s weather is changing and increasing the odds of damaging storms like the derecho. Much of Glisan’s job is helping farmers adapt to that reality—like preparing for more frequent heavy rainfall. (The probability of receiving more than three inches of rain in a 24-hour period in Iowa has tripled over the historical rate in the past 30 years.)

In the 2020 Iowa Farm and Rural Life poll, 81% of farmers said they believe climate change is occurring, up from 68% in 2011. That’s a much greater percentage than across Iowa’s general public, of whom 67% believe global warming is happening. (The rate is 72% nationally.)

I didn’t get to speak much to my parents during the 10 days they were in the dark, dealing with the derecho. Most attempts to call were met with understandable frustration about draining their phone battery. I know it was tough on them. My mom is still sometimes moved to tears when she talks about the volunteers—friends, family, and total strangers—who came with their chain saws to help them out. My family was lucky in that the trees that fell on their houses did not cause significant damage. My parents got a new roof, which was covered by insurance; my brother will get one in the spring.

I got the sense from them and others in Cedar Rapids, and I felt it myself when I visited in December, that one of the hardest things post-derecho was inhabiting a world of such obvious and inescapable physical loss, as if the landscape were reflecting their whole year’s experience back at them.

*****

The derecho wreaked havoc everywhere it hit. In Madrid (pronounced MAD-rid), 30 miles north of Des Moines, the storm peeled the roof off the four-floor Madrid Home, a senior living center, where six coronavirus patients were in isolation and receiving treatment on the facility’s top floor. Kris Hansen, CEO of Western Home Communities, which runs the site, was in a virtual meeting when he got the panicked call from his executive director in Madrid.

For Hansen, who was an hour to the northeast, in a part of the state where skies were still clear, it was an unthinkable twist. With 10 senior-living communities in the state of Iowa, the pandemic had been a real test for Western Home—for all the reasons familiar to long-term-care facilities across the country (a lack of PPE, a shortage of workers), and for reasons more specific to Iowa.

“I got frustrated with the governor a few times for not coming out stronger with a mask mandate,” he says, adding that it felt like the state had chosen the economy over protecting seniors. “Why would we put anybody at risk if we don’t have to? Our employees are still out in the community. They don’t have a choice.”

Western Home effectively guarded its sites against a COVID-19 outbreak until late July, when it experienced its first one in Madrid. The virus had slipped in during a visit from one of the facility’s contracted therapists. Over the course of a few days, six patients and three staff on the home’s first floor tested positive for COVID. It was tough on morale. “They were beating themselves up because they felt like they had failed,” says Hansen, who, like other health and long-term-care providers across the country, has been contending with a serious shortage of workers.

The fall brought scary and unspeakable tragedy to some of Western Home’s properties. The company had some managed-care facilities where nearly 100% of residents tested positive, and where workers, also positive, took care of them. “It just scares the crap out of you,” he tells me. “[My employees] have got families too.” The biggest challenge has been controlling the virus in dementia units. At one small facility in Cresco, Iowa, eight of 24 residents were lost to COVID. “We see what the results of this are,” he says of the state’s lax approach to the virus.

When I spoke with Hansen in mid-January, his staff and residents were still awaiting vaccines. Says Hansen: “It’s not rolling out nearly as fast as we had hoped.” He didn’t blame the state but the federal government, which is running the rollout in long-term-care facilities with the private sector. “It’s just not well-coordinated enough. We’ve got folks, quite honestly, that are going to die because of this, because of exposure that continues on.”

Hansen remains frustrated by the dynamics around the virus in Iowa. He noted that the day before we talked there had been an “Informed Choice Iowa” rally involving hundreds of unmasked Iowans in the rotunda of the Iowa state house (where state legislators are not required to wear masks, and many don’t). The group was calling for an end to COVID mandates. “I don’t know what happened to common sense in the middle of this whole pandemic,” says Hansen. “It’s just crap that this thing turned out to be as political as it did.”

*****

Naturally, I didn’t stop worrying about COVID when the derecho hit. I worried more. As Iowans will tell you, they come together in disasters. I imagined the virus spreading with all the goodwill.

Cedar Rapids did see cases peak slightly after the derecho and the immediate recovery, says St. Luke’s Hospital’s Niermann, but the situation wasn’t as bad as she feared it would be. “Masking went way down,” she told me. “Honestly, people had to work on a different level of hierarchy of needs.”

Far worse was yet to come. For much of the fall, Iowa was one of the nation’s COVID chart-toppers. The virus was everywhere, hitting rural counties especially hard. Despite growing cries from the public health community to do more, Gov. Reynolds again just asked Iowans to be responsible. As the curve climbed, the governor herself appeared on stage with President Trump and without a mask at an outdoor rally attended by thousands of his supporters in Des Moines.

In November, health facilities around the state began announcing that they were at or near capacity—they lacked either the staff or beds to handle more COVID patients. The governor responded with a set of complicated rules aimed at controlling the spread: no more than two spectators per child at an athletic event; face coverings should be worn at indoor gatherings of 25 or more, or outdoor gatherings of over 100. Finally, the week before Thanksgiving, Reynolds, in a tone that begged forgiveness—“No one wants to do this … I don’t want to do this”—issued a statewide mask mandate, albeit one with some exceptions.

*****

The mask rule couldn’t have come soon enough for Marshalltown Mayor Joel Greer. A lawyer by day, Greer had watched COVID stress his community since early spring. Marshalltown, a city of 28,000 smack dab in the middle of Iowa, is a meatpacking town, and like other Iowa cities it had had an early outbreak at its pork processing facility and largest employer, JBS. Dozens tested positive for the virus in April, and one local employee died a week before retirement in May.

It had just gone on from there. For Greer, it was a source of frustration and heartbreak that his county had at times been one of the most hard-hit in Iowa, while Iowa was one of the most hard-hit states in the country.

Greer Zoomed periodically with a group of mayors in central Iowa. Many wanted to issue mask mandates, something they technically didn’t have power to do. Some went ahead with it anyway. Unwilling to exceed his legal authority, Greer issued a mayoral proclamation requiring face coverings, with the caveat it couldn’t be enforced. It didn’t really catch on.

In October, Greer walked into a local bar to pick up a takeout order. The place was crowded, and while the staff were wearing masks, he was the only customer wearing one. The other patrons began making derogatory comments about him and questioning his manhood. “These people, they must have flunked science,” Greer tells me. “They just don’t get it.”

*****

Service workers in Marshalltown were among those who paid the price for the divide over mask-wearing. Alfonso Medina, the 31-year-old proprietor of La Carreta Mexican Grill, a popular Tex-Mex restaurant in the city, came down with COVID during the last week of November. He lost his sense of taste and smell, a symptom that, by that point in the year, he estimates 80% to 90% of his 17-person staff had already experienced. Since March, his team had tried to distance in the restaurant and take precautions. They had worn masks, but few customers did.

“It was very frustrating that customers didn’t have to wear them because it was almost causing this, to a point,” Medina told me in early January. “We could all be wearing masks, but we knew it’s just a matter of time before someone gets sick.”

While a couple of big-box stores in Marshalltown—Menards and Walmart—started requiring face coverings early in the pandemic, without a state mandate and as a minority-owned business, Medina thought it would be difficult to enforce a mask policy at La Carreta. His employees, particularly those in high school who worked part-time, weren’t comfortable confronting customers. He wished his patrons would just be responsible. “If you’re coming here to eat because this is your favorite restaurant, why wouldn’t you just wear one?” (Since the governor issued the statewide mandate, he says, almost everyone wears them.)

Medina prayed his staff wouldn’t all get sick at once and require him to shut down. The restaurant has actually done very well during the pandemic—he credits takeout alcohol sales for the fact that La Carreta had its best-ever Cinco de Mayo in 2020. And Medina says he was lucky to have gotten the virus himself during the quiet Thanksgiving week, at a time when his business could handle his 10-day absence.

Most of his employees had mild cases like his, and all eventually recovered, but nearly everyone on his team has lost someone to COVID: Medina’s 52-year-old uncle in Ohio; his parents’ 30-year-old physician in Mexico; his chef’s father; the grandfather of two servers; loyal customers. “Death has been all around us,” he says.

Medina was born in Roanoke, Va., and he spent his early childhood traveling around the country with his parents, immigrants from Mexico, as they built a growing business of Tex-Mex restaurants. They arrived in Iowa when he was 5 years old and later moved to Marshalltown, which he loved for its diversity, the good education he got, and the kindness of people generally. “It was a good place to grow up. You know, ‘Iowa nice,’ you really do see that,” he says.

When the pandemic began, Medina noticed many high-demand items—sanitizer, rice and beans, toilet paper—were available from his bulk suppliers. He made large orders and started reselling things locally; at one point, he was providing local nursing homes with gloves. Throughout the pandemic, he’s donated staples for local food-drive efforts and organized fundraisers for families who have lost members to COVID.

But Medina is probably best known for a slogan—“No love, no tacos”—that he promoted on a billboard in front of his restaurant, and on merchandise this fall. After the killings of George Floyd and other unarmed Black citizens by police last summer, Medina felt a responsibility to use his platform as a local business owner to be vocal about his values. He experimented on social media and got good feedback, so he placed a yard sign in front of La Carreta. It had, what seemed to him, nuggets of unimpeachable common sense: “Black lives matter”; “Human rights are women’s rights”; “Science is real.” But the sign prompted an angry, handwritten note on a receipt one day; the customer called the sign un-Christian. Medina posted a photo of the receipt on his personal Facebook page with his own note: “No love, no tacos.” He also set up a website and online clothing store under that banner, advocating for fairness and equality and that Election Day be made a federal holiday to ensure all can vote. Profits from the site went to a local scholarship fund Medina had previously established.

As things do, his message went viral, especially after he was featured by CNN in October in the run-up to the election. Orders for “No love, no tacos” hats and shirts poured in from around the world, and as people posted photos of themselves voting in November, many hashtagged them, #NoLoveNoTacos. The effort funded 14 scholarships to Marshalltown’s community college.

Medina says he received at least one letter that was far nastier than the note that had kicked off everything. I asked him if COVID and the current political climate had made Iowa less nice. He said he and his employees don’t talk politics in the restaurant for a reason.

“There’s people in Marshalltown with way different points of view, and I respect everybody’s point of view,” he says. “I have clientele here that have different party affiliations than mine. They walk in with whatever gear or whatever their shirt says, and I tell my employees, ‘We give them the same five-star service as anybody else.’”

*****

Mayor Greer has found that type of neutral ground increasingly hard to preserve. He laments how politicized the pandemic has become in his city. He’s taken heat over COVID—in emails, texts, and a whole lot of comments lobbed at his mayoral Facebook page—from both sides. “Half the people are mad as hell that school’s in session, the other half are mad that it’s not. It’s been pretty ugly,” he says.

Three years in, Greer’s tenure has involved dealing with one catastrophe after another in Marshalltown. One July day in 2018 a tornado literally traveled down Main Street, felling the courthouse’s clock tower and ransacking the historic district and downtown businesses, before damaging a number of homes in one of Marshalltown’s low-income neighborhoods. That made the derecho a surreal and especially cruel sequel of sorts.

Much of the burden of responding to these disasters has fallen on the shoulders of Kimberly Elder, emergency management coordinator for Marshall County. She’s been in her role since 2003, and every year, it seems, there are more disasters and fewer resources to deal with them. For much of 2020, she worked out of an office full of boxes. Some of them are filled with PPE, the county’s stockpile that she herself distributes to nursing homes and emergency responders. Others are file boxes, brimming with paperwork—the long tail of administrative business that follows a disaster. Elder hasn’t had a vacation in more than two years, and, as a one-woman shop, her biggest fear is getting sick with COVID. Says Elder: “If I’m in the hospital, like some of these people are, what are they going to do?”

Elder isn’t the only one mired in the process of recovery.

Some in the community have struggled more than others to get timely relief from insurers and state agencies. As Iowa cities go, Marshalltown is uniquely diverse, with a population that is 30% Hispanic, according to recent census data. Students in the Marshalltown school district are native speakers of more than 40 different languages; kindergartners in the district are 70% nonwhite. The meatpacking plant helped give rise to this multiculturalism because its jobs have drawn different populations to the city over time, including most recently Burmese and Congolese refugees.

In navigating the recovery process, language barriers are one issue; the other is time. The city’s immigrant population makes up a large part of Marshalltown’s essential workforce, employed in jobs that often don’t offer flexibility to deal with things like lining up an insurance adjuster.

*****

For some on the Meskwaki Settlement, the 8,000 acres of Tama County that is home to the Sac & Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa—east of Marshalltown—displacement because of the derecho came with another brutal cost: COVID.

Iowa’s only federally recognized tribe, the Meskwaki purchased the land in 1857 after resisting banishment by the federal government to a reservation in Kansas. Over the years the tribe expanded its holdings, and the settlement, where 1,200 or so tribal members currently reside, has its own health clinic, court, and school. In 1992 the Meskwaki opened a hotel and casino on the property—advertised as having “the loosest slots in Iowa”—which today provides about 70% of funding for tribal operations.

The derecho damaged 271 of the settlement’s 350 homes, and in the storm’s aftermath, the generator-powered hotel was the obvious place for those affected to go. Seven hundred tribal members “jam-packed” into the hotel, some five or six to a room, says Lawrence SpottedBird, the settlement’s executive director. People found themselves in proximity to people from whom they’d been socially distanced for months.

“We were interacting more closely and working more closely,” says SpottedBird. “We had to drop our guard to do that. The result was our cases spiked.”

The settlement, in some ways, had taken an opposite approach to the state’s in handling the pandemic. Rudy Papakee, health director at Meskwaki Tribal Health Clinic, learned of the community’s first COVID case in March. A tribal member had sought care at a hospital for breathing problems and tested positive for the virus. Soon the individual’s family members and their contacts did too. Several of the cases were severe, involving hospitalizations, and one elder who contracted the virus died.

“We were a little epicenter, at first,” says Papakee. He knew many in the population were vulnerable, either as elders or individuals with health conditions, like diabetes and high blood pressure, that put them at greater risk. Tribal leadership responded almost immediately with a shelter-in place order, shuttering the casino and other operations on the settlement. They continued to pay employees and asked them to stay home. They had a robust and accessible testing infrastructure, thanks to the Indian Health Service. When the tribe opened back up in early summer, it did so conservatively: It required face masks in public and canceled the annual powwow and other culturally important ceremonial gatherings.

But there were limitations to the effort. Many of the settlement’s residents work in nearby towns like Tama, Toledo, and Marshalltown, and everyone has to leave the settlement to get groceries and other supplies. The Meskwaki’s efforts to stop the spread of the virus could only be as good as the efforts in those surrounding communities.

“The state of Iowa was one of those states that didn’t take the virus too seriously,” says SpottedBird, who moved from Seattle to take his job in May (he’s not a tribal member). “So safeguards were kind of lackadaisical, loose, and people were generally not wearing masks for a long time.”

Like many health professionals in the state, Papakee has been frustrated greatly by Gov. Reynolds’s response to the pandemic. He would tune into her press conferences on the virus only to be dismayed each time by her continuing insistence that she trusted Iowans to make the right decisions. “Obviously you could not, because our numbers continued to soar,” he says.

He admits some of the same challenges exist on the settlement; there are those in the community who bristle at being required to wear masks or being told how to conduct their social lives. At one Christmas gathering on the settlement, a single person exposed 25 others. The casino, which provides the tribe with important revenue, reopened in July with a new nonsmoking policy, temperature checks, and masking and social distance requirements—a combination of measures that Papakee says have been effective but not perfect.

Vaccinations have started on the settlement, but Papakee had no idea when the next shipment was showing up, making things hard to plan. The community’s elders were anxiously awaiting their turn.

Reflecting trends seen across the country with Native American populations, the Meskwaki have been more impacted by the virus than other groups. When I spoke with Papakee, roughly a quarter of the settlement’s tribal population—301 people—had so far tested positive for COVID; five had succumbed to the virus.

*****

Outside the settlement, Shannon Zoffka, CEO of Tama County Public Health and Home Care, leads the area’s pandemic response. She has lived in the small, rural county of 17,000 all her life, but the past year has been eye-opening. “There’s definitely a large percent of the population in the county that don’t believe in masks. They think that the vaccine is unsafe; they think that COVID is a hoax,” Zoffka tells me one afternoon in early January.

That resistance to reality persists despite the county’s nursing home and meatpacking plant outbreaks, and the fact that Tama ranks in the top 4% of counties nationally in deaths per capita due to COVID. There was also a spike in cases after the derecho; the county had made community meals and cooling stations available to residents during the weeklong period they—and Tama County Public Health—went without power, making cases especially complicated to trace.

But things got really ugly at the start of the school year, as quarantines that were prescribed after known COVID-19 exposures started to affect sports. “People were very angry,” says Zoffka, who says her office’s attempts to investigate contacts or inform people of exposures to the virus were often met with verbal abuse. “People think they have the right to call you names and yell and scream and threaten.”

Soon she noticed people taking a different but equally bad-faith approach to her office’s outreach. “People got smart very fast when the definition of a close contact changed to being within six feet of someone for consecutive 15 minutes.” People said to the case investigators, “Well, you don’t have a tape measure or a stopwatch. You don’t know.” Or: “You can’t prove that we were there.”

While Zoffka’s team has had good support from partners like the school system, local business, law enforcement, and the Meskwaki Settlement, such attitude from community members was a disillusioning blow: “I don’t think we expected that early on. Our thought was, ‘We want to keep people safe. People want to keep other people safe.’ But then once [public health efforts] really affected their personal lives after some of the restrictions have been lifted, it got kind of rough.”

Given that, Zoffka says it was hard to stomach the governor’s continuing reliance on Iowans to “do the right thing” to control the virus. Beyond slowing the spread of disease, Zoffka says, a mask mandate would have supported businesses in the community who were trying to encourage safe behavior and often getting pushback.

In studying how the pandemic was playing out in Iowa—before I spoke with Zoffka—I had come across and become somewhat obsessed with Tama County Public Health’s Facebook page. The information was clear and the posts impressively transparent; the office regularly updated case numbers and explained why they were higher than the state’s (the state’s data was behind). Following the posts, you could also sense a growing, desperate pleading behind them: Wear a mask! Wash your hands! Protect your grandparents!

You only had to read the comments to get a sense of what the office was up against. While there were plenty of supportive and thankful followers, comments often enough devolved into heated arguments between citizens about why there were so many cases in the county. Others argued the whole thing was overblown.

Even though her team tries mightily to push out facts over their own Facebook page, Zoffka largely blames social media for the misinformation that has spread within the community about COVID, and for the harsh, bullying tone in which many discuss the virus, both online and increasingly in person. She expects hurt feelings and memories of the animosity that has emerged during COVID will linger, and that the doubters will remain. “I think people who don’t believe are never going to believe until they’re affected directly,” she says with some resignation.

When I spoke with Zoffka, her staff was working their way through administering its supply of Moderna vaccine doses. The logistics had been a challenge, particularly through the holidays, but it was going all right. She hasn’t had a lot of time to process what stage of the pandemic journey she’s in, or think much about the future. She’s just been responding—to questions about the virus, or the vaccine, or cases that need investigating, or all the other things that land on her desk. She’s hopeful that a lot of people will get vaccinated, and that maybe life will start inching its way back to normalcy by the end of the year. “I’ve kind of had it in my head that 2021 is going to be similar to 2020 in a lot of ways.”

*****

When the state climatologist Justin Glisan went out on his first trip to survey the derecho-impacted fields, the scene was staggering—acres and acres of corn blown flat, snapped off, or tipped so far over that it was not salvageable. Some of it had been further damaged by hail, shredded, as if it had taken on machine-gun fire.

“To stand in a field and to be able to look across it and realize I can see things I should not be able to see because the corn is just flat, it’s devastating” says Meaghan Anderson, a field agronomist with Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. She choked up for a moment, then added, “I have a job where I get a paycheck every two weeks. I don’t put hundreds of thousands of dollars upfront to plant something in April and then hope that, come September or October, I can harvest it and make my money back. That’s an incredible show of faith.”

Farmers that were hit didn’t lose just crops but also a lot of their infrastructure—the expensive equipment, the barns and grain bins. “We’re going to be dealing with this for years to come,” says Anderson.

Crop and other insurance covered much of the damage, but many, like Jenni and Scott Birker, still faced significant losses in 2020 because of the compound effect of the pandemic and the derecho. In recent years, the couple, who live in Benton County and raise beef cattle, watched their margins slim to almost nothing. “I’ve changed from being a cowboy basically to being a businessman. We’re picking up pennies and nickels every day out here,” Scott says.

But 2020 was a new type of challenge. Starting in February, with virus fears rattling markets, the Birkers weren’t able to secure their usual put option to ensure they covered the cost of their cattle. Then outbreaks started shuttering the state’s packing plants. Given the backlog of cattle waiting to be sold, the couple made the decision to modify their animals’ rations—“basically we put them on a 60-day diet”—to prolong the period before they took them to market. “We had to pay for that extra feed cost with no insurance on the cattle, which we thought was the right move at the time,” says Scott. “We didn’t have a clue what to do.”

And then the derecho hit. The Birkers lost their barn, chicken coop, miles of fence, and much of their corn crop, and had multiple tractors damaged. As they emerged from their basement after the storm, they found their five dozen chickens and laying hens scattered among the wreckage. Their cattle were all alive, but wandering free in the pasture. When they finally sold the cattle in October, it was for a loss. In all, it was a terrible year, but they have no plans to quit.

Others have had it even worse. And Anderson and others worry about the potential for farm bankruptcies to come as well as mental health issues among the agricultural community. (She knows of one farmer who committed suicide after the derecho.) Ag giant Cargill does too; it has sponsored some of the work the ISU extension service is providing for farmers and their families.

The bleak outlook is far from universal. For those who managed to harvest their crops, or who lived in a part of the state that didn’t get hit by the derecho or drought, yields were good in 2020 and corn prices have risen nicely since summer. Federal assistance in the form of trade payments and COVID relief have provided a generous cushion and were a good part of the reason that farmer incomes, on average, increased in 2020.

*****