今年3月中旬,当全世界像庞大的机器停止转动时,有个地方却仍然保留着常态,那就是Instagram。我全家人都在用这款照片视频分享APP:妈妈发她最新的艺术作品,我哥哥拍新出生的宝宝。所有的朋友都在这上面发照片或视频。我最喜欢的健身教练也会在Instagram Live上直播平常周六教的巴利舞蹈课程,布鲁克林发廊的造型师发视频教人修刘海,很多家纽约大热餐厅的厨师在自家厨房录制烹饪课程然后发到长视频平台IGTV,他们的厨房看起来跟我家的也差不多。几乎一夜之间,我的生活已经全部搬进了Instagram。

这并不是我在Instagram唯一的变化。正常工作状态已经远离,我不用穿笔挺的西装和通勤高跟鞋,Instagram时间线里的广告也发生了变化。现在,屏幕上充斥着毛绒运动裤、紧身裤和休闲套装等。变化还远远不只服装方面,还有杂货快递箱、在家办公桌和自制美甲套装等新型广告。而且没错,我都点击了。

当下的Instagram反映出,智能手机应用几乎完全能够捕捉和利用人们的生活方式。尽管有时迷失在强大母公司Facebook隐现的阴影之下(也有可能受到压制),但在2013年年底Instagram发布首条广告后,它俨然已经成长为营销巨头。2012年,全世界最大的社交网络以10亿美元收购照片应用Instagram,但并未透露这块业务的财务表现。有报道称,2019年Instagram的营收在200亿美元左右,约占Facebook总营收的四分之一。即使疫情流行期间,数字还在上升。摩根大通预计,今年Instagram的营收将增长20%以上,而外界预计投放Facebook核心应用的广告资金将保持平稳。与此同时,Instagram的目光已经超越了蓬勃发展的广告业务,开始关注更直接的“带货”。投行Cowen的高级研究分析师约翰•布莱克利奇表示,Instagram将成长为“新兴社交商业帝国”。

该应用之所以能成长为“吞金兽”,与Facebook有着千丝万缕的关系。Facebook以用户为目标且体量庞大,可以推动Instagram赚钱机器的运转。但Instagram也有其独特的优势,包括为不同人提供不同选择。你有没有被那些亮闪闪、精心设计、充满艺术感的奢侈品广告吸引过?然后你就会发现时间线里的类似的广告不计其数。如果你更喜欢直白更真实的内容,那Stories就能发挥作用,和Snapchat一样,Stories里面的照片和视频“阅后即焚”。即便你不喜欢广告,在面对喜欢的名人或其他“网红”的推荐时,你都能否招架得住?

可以说,Instagram实现了在线广告最初的承诺,引导你购买你确实需要的商品。正如数字产品代理公司Work&Co.的设计合伙人乔恩•杰克逊所说:“如果人们不在乎广告在销售什么,那这真是糟糕的广告。”

不过,营销的魔力很脆弱。甚至在新冠病毒颠覆世界经济之前,就有人提出疑问:Instagram能让用户持续关注多久?反垄断监管机构呼吁拆分Facebook,如果真是这样,Instagram就不能再使用其强大的算法。而且Instagram跟之前的社交媒体新生代一样,都面临着被新来者取代的威胁。当下的挑战者包括Snap和抖音国际版TikTok。而且,谁又敢说程序员在公寓里隔离时,会梦到什么聪明又令人上瘾的新应用呢?

不过,对于日常使用相关应用的人们来说,真正的问题是如果Instagram变得太优秀会怎样?早期Instagram之所以能在硅谷KPI驱动的世界里突飞猛进,主要是因为纯粹关注新创意。刚开始应用就是为了分享和欣赏美丽照片。Instagram的产品副总裁维沙尔•沙阿说,之后情况发生了很多变化,但很多用户还是去Instagram“寻找灵感”,这也是Instagram作为广告和购物平台运作良好的原因之一。他说得也没错。但随着Instagram不断探索获取新收入的方式,最后情况可能是,该平台只能提供如何花钱的灵感。

2013年11月,Instagram首次涉足广告。当时,Instagram的联合创始人凯文•塞斯特罗姆声称,每条广告都他都亲自审查,以维持平台的审美水准。2018年,塞斯特罗姆因为与Facebook的首席执行官马克•扎克伯格发生冲突而离开公司,当年严苛的规定也早已不复存在。事实上,在Instagram发广告最吸引人之处就是极其方便。eMarketer的首席分析师黛布拉•阿霍•威廉森表示:“就像勾选方框一样简单。”广告商使用的工具与投放Facebook广告相同,告诉公司目标客户在哪以及广告投放地点,或者干脆让Facebook帮着决定就可以。如果广告主想触达我这样的用户,Facebook会利用我在其应用和网上其他地方的行为辨识出我是女性,35岁到45岁,住在纽约市,喜欢设计、旅游和时尚,然后嗖一下,我的Instagram时间线上就会出现粉色旅行箱的广告。

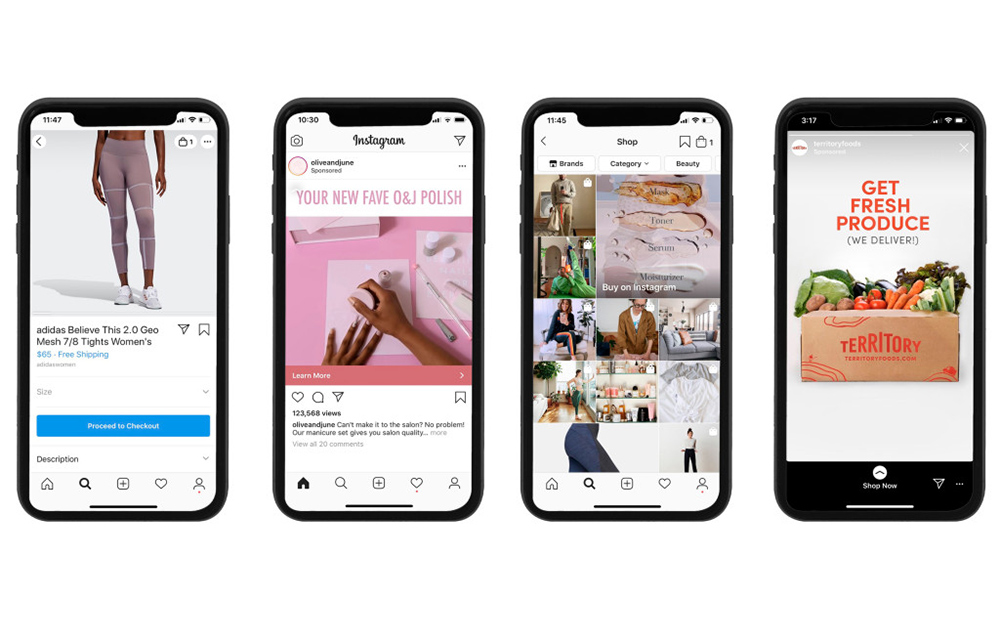

Facebook在数字广告市场几乎占据主导地位,市场份额基本上只输给谷歌一点,现在重心是推动Instagram转向下一个收入前沿——电商。自2017年以来,平台允许发布“购物帖”,即商家可以在照片中显示产品的定价信息,用户点击后直接跳转至零售商网站上的商品页面。2019年年初,Instagram深入商业领域,推出了结账功能,用户无需离开Instagram即可通过PayPal完成购买。只要输入一次付款和发货信息,之后几秒钟内就能够从入驻平台的卖家购买。每笔交易Instagram都会收取一定费用。

Facebook提供的数据显示,结账是迅速也很基本的操作,刚开始有22个品牌,现在发展到“数百个”。该项服务也有人质疑,称之过于简单,缺乏购物工具。但乐观的分析师认为其中蕴藏着巨大的机会。去年,德意志银行估计,到2021年,结账功能可以推动Instagram电商收入增至高达100亿美元。Instagram对母公司的重要之处还不仅在于刚刚起步的电商业务。分析师普遍认为,无论在用户还是广告收入方面,其增速都比Facebook核心应用更快。eMarketer估计,12岁至24岁的美国用户,也是各方争取的用户群体中,今年Instagram将超过Facebook,到2022年,Instagram将占据公司总收入的一半以上。由于成功地避免了困扰Facebook的虚假信息和数据隐私陷,公关方面Instagram也很省心。2019年皮尤研究中心的一项民调显示,只有29%的美国人能够正确指出Instagram和通讯应用WhatsApp属于Facebook。不管从哪个角度看,2012年扎克伯格花10亿美元收购Instagram都很值。“这是有史以来最成功的收购之一。没错。”Cowen的分析师布莱克利奇说。

我已经记不清具体从什么时候开始,我从在Instagram发照片变成了在Instagram购物。但这些年来,我在应用里下单或在应用里发现目标之后下单的数量急剧增加。我买过Rothy平跟鞋、Outdoor Voices紧身裤配连帽衫、Ferm Living的花盆,还有新买的Article抱枕。在写稿期间,我看到有个朋友穿着新跑步裤发布了Instagram Story,就发信息问她:“裤子从哪买的?”“Vuori。”她回答道,并补充说:“在Instagram买的:)”现在我的新裤子正在送往公寓的路上。

我对自己的行为并不骄傲,但我知道像我一样的人并不少。Cowen最近的一份报告发现,在18至35岁的用户里,近40%从Instagram上发现的品牌买过东西。总体而言,约13%的美国Instagram用户承认直接通过应用购买过商品,超过60%的用户表示“关注”了品牌账户。

Instagram如此讨喜的原因很简单:美丽的照片。其美感已经渗透到现实世界,也让公共和私人场所“处处皆可ins风”,引发了 #OOTD (发布“今日搭配”照片的概念),还催生出了所谓的千禧一代设计风格,即火遍应用内外的弱粉色无衬线字体。

Instagram也改变了数字广告。早期塞斯特罗姆把关的原则一直存在,到最后时间线上的广告看起来要像朋友可能发布的东西,而且要更好看。通过应用里最受欢迎的广告界面Stories,营销者学会了自然和不加修饰的重要性。利用该功能,品牌可以将一系列照片和视频打包,最理想的情况是不让用户感觉到在沉重的前提下传递大量信息。“IG Stories是向全世界介绍品牌最有力的工具。”营销机构Good Moose的首席执行官兼联合创始人丹尼尔•罗马诺说。

如果谈论Instagram,就无法避开网红,也就是应用里还有YouTube上聚集的有些奇怪的类明星群体。据营销平台Influencer Marketing Hub统计,去年市场营销人员在网红身上投的钱约为65亿美元。网红“创造者”是应用里推动销售的“秘方”关键,首批试用Instagram结账功能的阿迪达斯数字合作高级主管谢丽尔•马洛尼表示。她举了个例子,玩家忍者跟德雷克玩《堡垒之夜》游戏直播打破了平台纪录,在当上网红后,他就能够号召粉丝到Instagram看比赛,并购买阿迪达斯的最新款“drop”休闲鞋。

当然,现在的问题是,在疫情过去之后,构建电商帝国的数字积木能否保持稳固,哪一块可能变松,导致整体结构摇摆。网红经济肯定面临风险,因为居家令限制了镜头前的生活方式,炫耀性消费也与新闻中每日死亡人数的沉重氛围存在冲突。Facebook曾经表示,病毒导致广告业务“急剧放缓”,认为未来将出现“前所未有的不确定性”。但与此同时,全球范围内的封锁也推动应用用户数量和参与度大幅飙升,困在家里的人们开始改变使用方式。4月的财报电话会上,扎克伯格说每天在Instagram和Facebook观看直播视频的用户多达8亿人。相比之下,今年美国超级碗的观众仅为约1.02亿。

Instagram很清楚,必须在“原生”帖子(比如同事分享新做的面包)和付费内容之间维持平衡。“对于规模庞大Instagram,甚至普通用户来说,并不存在简单统一的答案。”Instagram的沙阿说。该公司利用数据在喜欢广告的用户面前投放更多广告,至于不喜欢广告的用户,就少投放。

至于我,泡在应用里的时间比以往都多。iPhone屏幕使用时间统计显示,最近一周日均6小时24分钟。但我发帖变少了,今年以来只发过两张照片。毫无疑问,主要原因是在过去两个月内,我一直被困在不太适合拍照的公寓里,这也反映了我跟应用关系的转变。等到能重新走出去看外面的世界,我希望用Instagram的方式能更接近2012年刚下载时:发挥创意,而不仅仅是消费。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年6/7月刊。

译者:Feb

今年3月中旬,当全世界像庞大的机器停止转动时,有个地方却仍然保留着常态,那就是Instagram。我全家人都在用这款照片视频分享APP:妈妈发她最新的艺术作品,我哥哥拍新出生的宝宝。所有的朋友都在这上面发照片或视频。我最喜欢的健身教练也会在Instagram Live上直播平常周六教的巴利舞蹈课程,布鲁克林发廊的造型师发视频教人修刘海,很多家纽约大热餐厅的厨师在自家厨房录制烹饪课程然后发到长视频平台IGTV,他们的厨房看起来跟我家的也差不多。几乎一夜之间,我的生活已经全部搬进了Instagram。

这并不是我在Instagram唯一的变化。正常工作状态已经远离,我不用穿笔挺的西装和通勤高跟鞋,Instagram时间线里的广告也发生了变化。现在,屏幕上充斥着毛绒运动裤、紧身裤和休闲套装等。变化还远远不只服装方面,还有杂货快递箱、在家办公桌和自制美甲套装等新型广告。而且没错,我都点击了。

当下的Instagram反映出,智能手机应用几乎完全能够捕捉和利用人们的生活方式。尽管有时迷失在强大母公司Facebook隐现的阴影之下(也有可能受到压制),但在2013年年底Instagram发布首条广告后,它俨然已经成长为营销巨头。2012年,全世界最大的社交网络以10亿美元收购照片应用Instagram,但并未透露这块业务的财务表现。有报道称,2019年Instagram的营收在200亿美元左右,约占Facebook总营收的四分之一。即使疫情流行期间,数字还在上升。摩根大通预计,今年Instagram的营收将增长20%以上,而外界预计投放Facebook核心应用的广告资金将保持平稳。与此同时,Instagram的目光已经超越了蓬勃发展的广告业务,开始关注更直接的“带货”。投行Cowen的高级研究分析师约翰•布莱克利奇表示,Instagram将成长为“新兴社交商业帝国”。

该应用之所以能成长为“吞金兽”,与Facebook有着千丝万缕的关系。Facebook以用户为目标且体量庞大,可以推动Instagram赚钱机器的运转。但Instagram也有其独特的优势,包括为不同人提供不同选择。你有没有被那些亮闪闪、精心设计、充满艺术感的奢侈品广告吸引过?然后你就会发现时间线里的类似的广告不计其数。如果你更喜欢直白更真实的内容,那Stories就能发挥作用,和Snapchat一样,Stories里面的照片和视频“阅后即焚”。即便你不喜欢广告,在面对喜欢的名人或其他“网红”的推荐时,你都能否招架得住?

可以说,Instagram实现了在线广告最初的承诺,引导你购买你确实需要的商品。正如数字产品代理公司Work&Co.的设计合伙人乔恩•杰克逊所说:“如果人们不在乎广告在销售什么,那这真是糟糕的广告。”

不过,营销的魔力很脆弱。甚至在新冠病毒颠覆世界经济之前,就有人提出疑问:Instagram能让用户持续关注多久?反垄断监管机构呼吁拆分Facebook,如果真是这样,Instagram就不能再使用其强大的算法。而且Instagram跟之前的社交媒体新生代一样,都面临着被新来者取代的威胁。当下的挑战者包括Snap和抖音国际版TikTok。而且,谁又敢说程序员在公寓里隔离时,会梦到什么聪明又令人上瘾的新应用呢?

不过,对于日常使用相关应用的人们来说,真正的问题是如果Instagram变得太优秀会怎样?早期Instagram之所以能在硅谷KPI驱动的世界里突飞猛进,主要是因为纯粹关注新创意。刚开始应用就是为了分享和欣赏美丽照片。Instagram的产品副总裁维沙尔•沙阿说,之后情况发生了很多变化,但很多用户还是去Instagram“寻找灵感”,这也是Instagram作为广告和购物平台运作良好的原因之一。他说得也没错。但随着Instagram不断探索获取新收入的方式,最后情况可能是,该平台只能提供如何花钱的灵感。

2013年11月,Instagram首次涉足广告。当时,Instagram的联合创始人凯文•塞斯特罗姆声称,每条广告都他都亲自审查,以维持平台的审美水准。2018年,塞斯特罗姆因为与Facebook的首席执行官马克•扎克伯格发生冲突而离开公司,当年严苛的规定也早已不复存在。事实上,在Instagram发广告最吸引人之处就是极其方便。eMarketer的首席分析师黛布拉•阿霍•威廉森表示:“就像勾选方框一样简单。”广告商使用的工具与投放Facebook广告相同,告诉公司目标客户在哪以及广告投放地点,或者干脆让Facebook帮着决定就可以。如果广告主想触达我这样的用户,Facebook会利用我在其应用和网上其他地方的行为辨识出我是女性,35岁到45岁,住在纽约市,喜欢设计、旅游和时尚,然后嗖一下,我的Instagram时间线上就会出现粉色旅行箱的广告。

Facebook在数字广告市场几乎占据主导地位,市场份额基本上只输给谷歌一点,现在重心是推动Instagram转向下一个收入前沿——电商。自2017年以来,平台允许发布“购物帖”,即商家可以在照片中显示产品的定价信息,用户点击后直接跳转至零售商网站上的商品页面。2019年年初,Instagram深入商业领域,推出了结账功能,用户无需离开Instagram即可通过PayPal完成购买。只要输入一次付款和发货信息,之后几秒钟内就能够从入驻平台的卖家购买。每笔交易Instagram都会收取一定费用。

Facebook提供的数据显示,结账是迅速也很基本的操作,刚开始有22个品牌,现在发展到“数百个”。该项服务也有人质疑,称之过于简单,缺乏购物工具。但乐观的分析师认为其中蕴藏着巨大的机会。去年,德意志银行估计,到2021年,结账功能可以推动Instagram电商收入增至高达100亿美元。Instagram对母公司的重要之处还不仅在于刚刚起步的电商业务。分析师普遍认为,无论在用户还是广告收入方面,其增速都比Facebook核心应用更快。eMarketer估计,12岁至24岁的美国用户,也是各方争取的用户群体中,今年Instagram将超过Facebook,到2022年,Instagram将占据公司总收入的一半以上。由于成功地避免了困扰Facebook的虚假信息和数据隐私陷,公关方面Instagram也很省心。2019年皮尤研究中心的一项民调显示,只有29%的美国人能够正确指出Instagram和通讯应用WhatsApp属于Facebook。不管从哪个角度看,2012年扎克伯格花10亿美元收购Instagram都很值。“这是有史以来最成功的收购之一。没错。”Cowen的分析师布莱克利奇说。

我已经记不清具体从什么时候开始,我从在Instagram发照片变成了在Instagram购物。但这些年来,我在应用里下单或在应用里发现目标之后下单的数量急剧增加。我买过Rothy平跟鞋、Outdoor Voices紧身裤配连帽衫、Ferm Living的花盆,还有新买的Article抱枕。在写稿期间,我看到有个朋友穿着新跑步裤发布了Instagram Story,就发信息问她:“裤子从哪买的?”“Vuori。”她回答道,并补充说:“在Instagram买的:)”现在我的新裤子正在送往公寓的路上。

我对自己的行为并不骄傲,但我知道像我一样的人并不少。Cowen最近的一份报告发现,在18至35岁的用户里,近40%从Instagram上发现的品牌买过东西。总体而言,约13%的美国Instagram用户承认直接通过应用购买过商品,超过60%的用户表示“关注”了品牌账户。

Instagram如此讨喜的原因很简单:美丽的照片。其美感已经渗透到现实世界,也让公共和私人场所“处处皆可ins风”,引发了 #OOTD (发布“今日搭配”照片的概念),还催生出了所谓的千禧一代设计风格,即火遍应用内外的弱粉色无衬线字体。

Instagram也改变了数字广告。早期塞斯特罗姆把关的原则一直存在,到最后时间线上的广告看起来要像朋友可能发布的东西,而且要更好看。通过应用里最受欢迎的广告界面Stories,营销者学会了自然和不加修饰的重要性。利用该功能,品牌可以将一系列照片和视频打包,最理想的情况是不让用户感觉到在沉重的前提下传递大量信息。“IG Stories是向全世界介绍品牌最有力的工具。”营销机构Good Moose的首席执行官兼联合创始人丹尼尔•罗马诺说。

如果谈论Instagram,就无法避开网红,也就是应用里还有YouTube上聚集的有些奇怪的类明星群体。据营销平台Influencer Marketing Hub统计,去年市场营销人员在网红身上投的钱约为65亿美元。网红“创造者”是应用里推动销售的“秘方”关键,首批试用Instagram结账功能的阿迪达斯数字合作高级主管谢丽尔•马洛尼表示。她举了个例子,玩家忍者跟德雷克玩《堡垒之夜》游戏直播打破了平台纪录,在当上网红后,他就能够号召粉丝到Instagram看比赛,并购买阿迪达斯的最新款“drop”休闲鞋。

当然,现在的问题是,在疫情过去之后,构建电商帝国的数字积木能否保持稳固,哪一块可能变松,导致整体结构摇摆。网红经济肯定面临风险,因为居家令限制了镜头前的生活方式,炫耀性消费也与新闻中每日死亡人数的沉重氛围存在冲突。Facebook曾经表示,病毒导致广告业务“急剧放缓”,认为未来将出现“前所未有的不确定性”。但与此同时,全球范围内的封锁也推动应用用户数量和参与度大幅飙升,困在家里的人们开始改变使用方式。4月的财报电话会上,扎克伯格说每天在Instagram和Facebook观看直播视频的用户多达8亿人。相比之下,今年美国超级碗的观众仅为约1.02亿。

Instagram很清楚,必须在“原生”帖子(比如同事分享新做的面包)和付费内容之间维持平衡。“对于规模庞大Instagram,甚至普通用户来说,并不存在简单统一的答案。”Instagram的沙阿说。该公司利用数据在喜欢广告的用户面前投放更多广告,至于不喜欢广告的用户,就少投放。

至于我,泡在应用里的时间比以往都多。iPhone屏幕使用时间统计显示,最近一周日均6小时24分钟。但我发帖变少了,今年以来只发过两张照片。毫无疑问,主要原因是在过去两个月内,我一直被困在不太适合拍照的公寓里,这也反映了我跟应用关系的转变。等到能重新走出去看外面的世界,我希望用Instagram的方式能更接近2012年刚下载时:发挥创意,而不仅仅是消费。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年6/7月刊。

译者:Feb

As the world screeched to a halt in the middle of March, there was one place where I could still find normality: Instagram. My family was there—my mom sharing her latest artwork; my brother’s shots of his new baby—as were my friends, both real and aspirational. (DM me anytime, Chrissy Teigen!) But now I could also find a favorite fitness instructor teaching his usual Saturday barre class on Instagram Live, the stylists from my Brooklyn hair salon posting bang-trim tutorials, and the chefs of many of New York’s most beloved restaurants leading IGTV cooking lessons from home kitchens not so different from my own. Almost overnight, the life I used to lead in, well, life, had relocated to Instagram.

And that wasn’t the only change happening in my Instagram existence. As I temporarily retired workwear staples like sharp-shouldered blazers and commute-friendly heels, the ads filling my Instagram feed transformed as well. The screen was now bursting with sponsored posts for “plush upstate sweatpants,” leggings, and loungewear sets. The shift went far beyond clothing, to new-to-me ads for grocery delivery boxes, work-from-home desks, and DIY manicure sets. And, yes, reader: I clicked.

Instagram is having a moment, one that reveals the ways in which the smartphone app is almost perfectly positioned to capture—and capitalize on—The Way We Live Now. Since Instagram posted its first ad in late 2013, it has grown into a marketing juggernaut, albeit one that is sometimes lost in (or perhaps sheltered by) the looming shadow of its powerful parent, Facebook. The world’s preeminent social network, which acquired the photo app for $1 billion in 2012, doesn’t break out Instagram’s fi¬nances. But news reports peg the unit’s 2019 revenues in the $20 billion range, or about a quarter of Facebook’s total. And even amid a pandemic, that number is on the upswing. J.P. Morgan projects that Instagram revenues will climb more than 20% this year, despite the expectation that ad money being pumped into the core Facebook app will stay flat. Meanwhile, Instagram is already looking beyond its booming ad business, setting its sights on selling us stuff more directly. It is, says Cowen senior research analyst John Blackledge, “an emerging social commerce powerhouse.”

The app’s evolution into one of the Internet’s most potent tools for separating users from their cash cannot be severed from its relationship with Facebook. The parent, with its user targeting and sheer scale, provides Instagram the engine to turbocharge its own moneymaking machine. But Instagram also brings unique strengths to the endeavor, including its ability to be many things to many people. Are you tempted by the kind of carefully composed, art-directed ads you might see in a luxury glossy? You’ll find an endless supply on your feed. Or maybe you prefer your brands chatty, unscripted, and “authentic.” That’s what Stories—Instagram’s Snapchat-esque feature for disappearing photos and videos—is for. And if the very idea of an ad is a turnoff, how about getting a recommendation or 12 from your favorite celebrity or other “influencer”? They’re all on the app, tagging and sharing their way through their closets, homes, social lives, and vacations.

At its best, Instagram delivers on online advertising’s original promise, to be a helpful service that steers you toward things you actually want. As Jon Jackson, design partner at digital product agency Work & Co., puts it: “An ad only sucks if you don’t care about what it’s selling.”

That marketing magic is fragile, though. Even before the coronavirus upended the world’s economic expectations, there were plenty of questions about how long Instagram can keep us caring. Antitrust regulators yearn for Facebook to be broken up, a move that would deprive Instagram of its parent’s valuable algorithms. And Instagram, like all the cool kids of social media before it, faces the existential threat of being displaced by the new new thing. Today’s challengers include Snap and TikTok, but who’s to say what brilliant and deviously addictive new app some coder is dreaming up while quarantining in her apartment right now?

For those of us who have made the app part of our daily routine, though, the real question is, what happens if Instagram gets too good? In its early days, part of what made Instagram radical within the KPI-driven world of Silicon Valley was its focus on creativity for creativity’s sake. It was just a place to share and appreciate gorgeous photos. A lot has changed since then, but people still come to Instagram “to be inspired,” which is one of the reasons it works so well as an ad and shopping platform, says Vishal Shah, Instagram’s VP of product. He’s not wrong. But as the app continues to explore new ways to drive revenue, it risks reaching the point where the only thing it inspires us to do is spend money.

****

Instagram first dipped its toe into the advertising world in November 2013. At the time, Instagram cofounder Kevin Systrom claimed he personally vetted each ad in an effort to keep the platform’s aesthetic bar high. Fast-forward to 2020: Both Systrom, who left the company in 2018 amid conflicts with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, and those stringent rules are long gone. Indeed, one of the most appealing aspects of advertising on Instagram is how easy the process is. “It’s literally checking a box,” says Debra Aho Williamson, principal analyst at eMarketer. Advertisers use the same tool that places Facebook ads; they tell the company whom they want to target and where the ad should run—or simply let Facebook make that decision for them. If that company is trying to reach, say, someone like me, Facebook uses my behavior on its apps (both Facebook and Instagram if the accounts are linked, as mine are) and elsewhere on the Internet to see that I’m a woman, age 35 to 45, living in New York City, who likes design, travel, and fashion, and—boom—that ad for the blush-pink Away suitcase lands in my Instagram feed.

Having established near domination in the digital ad market—only Google gets a larger share of the pie—Facebook is now pivoting Instagram toward the next revenue frontier, e-commerce. Since 2017, the platform has allowed for “shoppable posts,” in which a merchant can display pricing information about products shown in a photo, and with a tap take users directly to that item on the retailer’s site. In early 2019, Instagram waded deeper into the world of commerce, launching Checkout, which enables users to buy via PayPal without leaving Instagram. Shoppers enter their payment and shipping information once and then can buy from any of the participating sellers in seconds. Instagram takes a cut of all sales.

Checkout is still a small-time and rudimentary operation—it started with 22 brands and now involves “hundreds,” according to Facebook. The service has its share of skeptics, who call it bare-bones for its lack of shopping tools. But bullish analysts see a big opportunity. Last year, Deutsche Bank estimated Checkout could help drive Instagram’s e-commerce revenue to as much as $10 billion by 2021. And it’s not just its fledgling e-commerce business that makes Instagram essential to its parent. Analysts generally believe Instagram is growing faster, both in ¬users and in ad revenue, than the core Facebook app. eMarketer estimates that Instagram will surpass Facebook this year in terms of U.S. users age 12 to 24—a coveted demographic—and that by 2022, it will be responsible for more than half of the company’s total revenue. Instagram represents a PR coup for Facebook, too, as the photo app has managed to avoid most of the misinformation and data privacy pitfalls that have dogged Facebook. According to a 2019 poll by Pew Research Center, just 29% of Americans correctly identified Instagram and messaging service WhatsApp as being owned by Facebook. Either way, the $1 billion Zuckerberg spent to buy Instagram in 2012 was money well spent. “It’s one of the best acquisitions in history. Period,” says Blackledge, the analyst with Cowen.

****

I can’t recall the exact moment I crossed over from Instagram photo poster to Instagram shopper. But over the years, the number of purchases I made or first spotted on the app has snowballed. There’s the pointy-toed Rothy’s flats, the Outdoor Voices leggings with matching hoodie, the Ferm Living planter, our new Article throw pillows. In the midst of writing this story, I messaged a friend who’d posted an Instagram Story of herself in some new joggers, asking, “Where are they from?” “Vuori,” she responded, adding: “Instagram buy :)” A pair are now en route to my apartment.

I’m not exactly proud of this behavior—but I know I’m not alone. A recent report from Cowen found nearly 40% of users ages 18 to 35 had bought something from a brand they discovered on Instagram. Overall, about 13% of U.S. Instagrammers said they had made a purchase directly through the app, and more than 60% said they “follow” a brand’s account.

The main reason Instagram is so pleasantly browsable is simple: pretty photos. Much has been made of how its aesthetic has spilled out into the physical world—remaking our public and private places to be “Instagrammable,” spawning #OOTD (the concept of posting a photo of your “outfit of the day”) and helping birth so-called millennial design—the muted pastels and sans serif fonts that rage on and off the app.

Instagram also has transformed digital advertising. The discipline of Systrom’s early gatekeeping has persisted; the ultimate news feed ad looks just like something one of your friends might post—only better. And one of the app’s most popular ad surfaces, Stories, has taught marketers the value of appearing spontaneous and unpolished. It’s a place where brands can string together a series of photos and videos, ideally conveying a ton of information without feeling heavy-handed. “IG Stories is the most powerful tool you can use to introduce your brand to the world,” says Daniel Romano, CEO and cofounder of marketing agency Good Moose.

And you can’t talk about Instagram without talking about influencers, the strange universe of digital demi-celebrities that the app, along with YouTube, created. Marketers spent an estimated $6.5 billion last year on influencers, according to Influencer Marketing Hub. These “creators” are a key part of the “formula” for selling things on the app, says Sheryl Maloney, senior director of digital partnerships at Adidas, an Instagram Checkout pioneer. She cites Ninja, a gamer known for, among other things, breaking streaming records while playing Fortnite with Drake, as an example of someone with the online clout required to get his followers to come to the platform to see—and buy—Adidas’s latest new “drop.”

The immediate question, of course, is which of these digital Jenga pieces will hold firm in a post-COVID-19 world, and which will come loose, leaving the whole structure swaying. The influencer economy is certainly at risk, as stay-at-home orders crimp their photogenic lifestyles, and messages of conspicuous consumption clash with the daily death toll in the news. Facebook has said that the ¬virus has created a “steep slowdown” in its ad business and that it sees “unprecedented uncertainty” ahead. But at the same time, global lockdowns have prompted a massive spike in ¬users and engagement on its apps, and people, stuck at home, are starting to change how they behave when they use them. On an April earnings call, Zuckerberg said that 800 million people are now tuning into live video on Instagram and Facebook daily. By way of comparison, about 102 million people watched this year’s Super Bowl in the U.S.

Instagram knows it must strike a balance between “organic” posts (like when your coworker shares a shot of his latest loaf of sourdough) and paid content. “There’s no one monolithic answer for all of Instagram or even any one person,” says Instagram’s Shah. Instead, the company uses data to try to put more ads in front of users who welcome them—and fewer in front of those who don’t.

As for me, I’m on the app more than ever: six hours and 24 minutes one recent week, according to my iPhone’s Screen Time report. But my posting became anemic—just two photos in my feed so far all year. No doubt the fact that I’ve been stuck in my less-than-photogenic apartment for the past two months has had something to do with that, but I think it also reflects a shift in my relationship with the app. When it’s time to reenter the outside world, I hope I can get closer to the way I used Instagram when I joined, back in 2012: to create, not just to consume.

A version of this article appears in the June/July 2020 issue of Fortune.