一直以来,企业投入大量时间和精力寻求创新,然而很多好创意往往来自内部。19世纪,宝洁公司一位化学家认为,漂浮在浴缸中的肥皂能使沐浴体验更欢快,于是研发了象牙肥皂。20世纪70年代,3M一位员工希望阅读赞美诗时更方便标记页面,修改了几年前同事发明但尚未商业化应用的粘合剂;后来便利贴成了3M公司标志性的成功产品。佳明原本是堪萨斯州郊区一家船舶、飞机和汽车导航设备制造商,一群痴迷于跑步的员工将专业知识与爱好结合,在公司急需胜利时助力东山再起。

当时是21世纪初,佳明利用政府的全球定位系统(GPS)技术,在消费设备的小众市场成长了起来。佳明还跟竞争对手TomTom一起主导车内导航设备市场,该款设备也宣告纸质地图时代步入终结。其实佳明慢跑爱好者想起该创意之前,GPS个人健身设备并不受欢迎。“有员工说,‘既然我们的工作本来就跟GPS相关,为什么不为跑步者提供产品呢?”从业31年的佳明首席执行官克里夫•彭布尔回忆道。

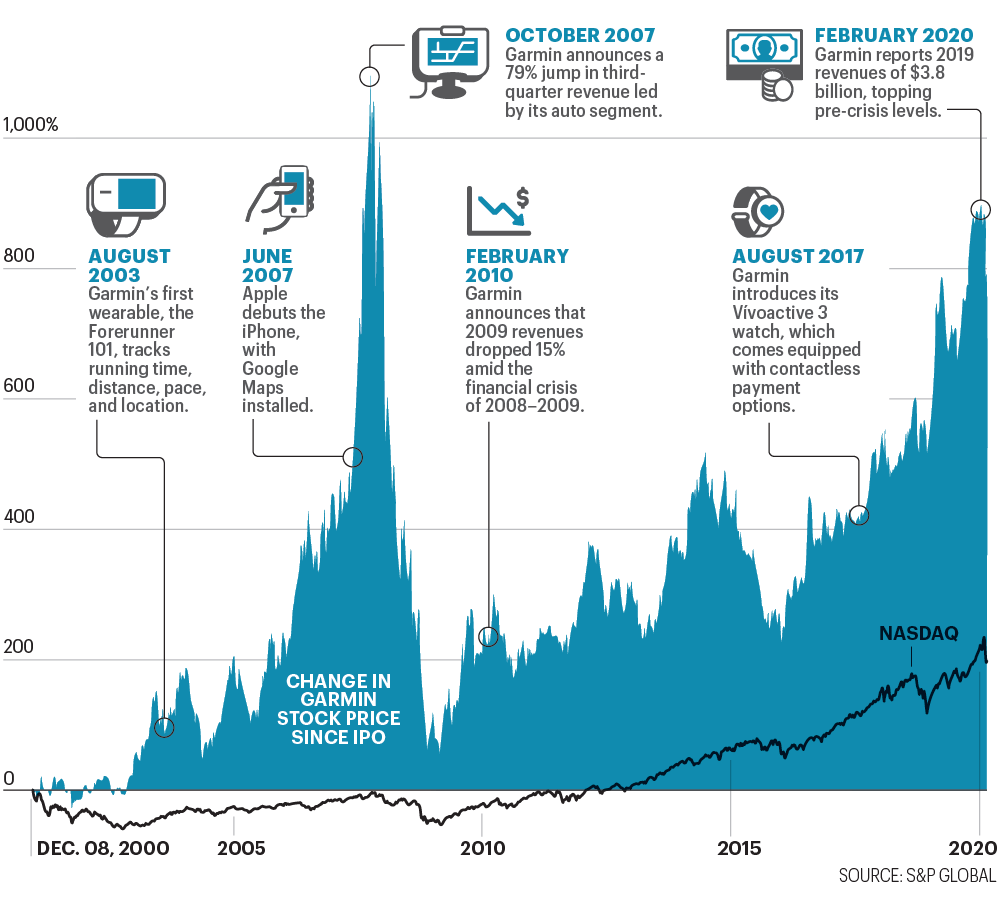

2003年,佳明推出了第一款跑步手表,即Forerunner 101。如今,员工发起的产品已发展近20年,在苹果iPhone结合谷歌地图技术抢夺佳明的核心汽车业务后,可穿戴产品的意义显得越发重大。佳明已成为业内罕见远离硅谷的公司,而且受到科技巨头重创后仍能在竞争中蓬勃发展。去年手表和其他可穿戴设备约占38亿美元营收的三分之一。公司估值达150亿美元,虽然跟竞争对手苹果、Alphabet和三星相比微不足道,但在细分市场也是重要的竞争者。

佳明抵御科技行业冲击的方式,是企业坚持擅长领域最好的范例。具体来说,佳明的新产品结合了关键技术即GPS设备,也证明了并不是只有加州北部阳光普照的土地能孕育创新。佳明身上体现出的中西部气质和逆境下的韧性,正是其持久的原因。举个例子,很难想象佳明的大型竞争对手会承认,打进杀手级应用程序的领域或多或少是种幸运。“我们可能低估了可穿戴设备的重要性,”彭布尔说。“当时就是试试水。没人能想到会成长为今天的体量。”

当然,科技巨头仍然会威胁佳明生存,苹果和三星是智能手表的两大巨头,Alphabet旗下的谷歌正收购其竞争对手Fitbit。“向大众销售手表需要不同的产品,思路跟现在(佳明)的做法完全不同。”市场研究机构NPD Group的分析师史蒂芬·贝克说。“能成功做到的企业极少,有勇气去尝试的企业都不多。”

佳明并没有打算征服大众市场,一开始就专为划船运动员、飞行员和越野车爱好者提供小众产品。公司创始人加里·伯瑞尔和高民环之前在Allied Signal担任工程师,1989年创立时GPS还刚刚投入民用。(听起来颇为阳刚的公司名Garmin是二人名字结合)。对爱好者来说,平价导航系统是个意外发现,可以将之前仅供尖端军事装备的技术用在民用设备中。

1991年,佳明发布了首款名叫GPS 100的产品,目标是小型船只和飞机,非常受欢迎,年底公司就已盈利。七年后佳明推出的新产品将数字地图放进车里,也由此蜚声内外。汽车导航“公司开创的产品类别,”彭布尔说,现年54岁的彭布尔是佳明第六位员工。“汽车导航成了公司发展的动力,也让佳明转型消费品牌。”

发展过程中,佳明充分发挥了中西部精神的优势,企业文化非常强调勤奋和谦逊。“他们很清楚如何充分发挥员工的潜能,”前系统工程师约瑟夫•里德说,他经常负责向高级管理层汇报工作。“会表扬,也会批评,”曾在佳明担任市场分析师的斯蒂芬妮·芒顿说:“鼓励员工挑战极限。”

佳明之所以发展稳健,部分原因是内部联系非常严密。去年去世的伯瑞尔是虔诚的基督徒,享年81岁,他自称“服务型领导”,对公司上下的影响如涓涓细流。“他连我妻子和孩子的名字都知道,”2000年至2016年在佳明工作的里克·埃文斯说。“他对每个人都很了解。”

遇到上个10年末的艰难时期,内部团结一致发挥了巨大作用。2007年,佳明推出了汽车、卡车和摩托车约40种车载GPS型号,处于飞速发展时期。汽车导航部门销售额达到23亿美元,同比翻了一番多,占总销售额近74%。然而当年年中苹果发布了iPhone,手机上预装了谷歌地图。iPhone第一个版本并无GPS芯片,主要靠初级技术精确定位位置。但不到一年,苹果手机就整合了GPS,在很多方面可取代佳明的设备。

佳明的业务立即受到冲击,随后的金融危机导致问题更严重。2008年股价暴跌,从2007年超过120美元的高点跌至每股16美元以下。一如华尔街担心,2009年佳明收入下降了5亿美元,降至30亿美元。尽管佳明盈利稳定,当年赚了7.04亿美元,投资者还是很不安。“当时(投资者)都说,‘佳明有可能撑不下去,’”美国银行分析师罗恩•爱泼斯坦表示。

高民环当时担任佳明首席执行官,如今仍担任执行总裁。他保持冷静,将投资重点放在汽车导航之外的业务。举例来说,之后十年佳明收购了全球25家公司,大部分是导航设备分销商,扩大了地理范围,还收购了可访问天气信息以及嵌入可穿戴设备的非接触支付技术。首席执行官彭布尔表示,佳明从未忽视增长的必要性。他说:“最有效的做法就是加倍努力寻求增长和机会。”他说。“省钱和削减开支基本没什么用。”

佳明的产品创新并非完美无缺。2008年,佳明推出了自家的GPS智能手机Nüvifone,使用了谷歌的安卓操作系统。手机零售价为300美元,相当昂贵,触摸屏反应不太灵敏,而且经常分不清用户滑动和点击屏幕的操作。相机质量很差,不能拍摄视频。在该款手机上查看天气、交通和本地活动要交6美元,而在苹果和其他手机上都是免费的。两年半后,佳明退出了智能手机业务。

事实证明,佳明在产品开发方面表现最稳,与硅谷寻求快速发展和突破的风格迥异。不过,这种特质有助于公司进入受监管行业,特别是航空业,因为比起上市时间,航空业更重视精确性。“我曾在苹果公司工作,知道他们行动速度多快,”曾在佳明担任软件工程师的马特·荣格说。“佳明做事的节奏非常不一样。”

说起佳明产品进展缓慢,最有代表性的莫过于健身手表,如今佳明手表逐渐变成希望用GPS技术精确定位的铁杆运动员最爱。“GPS功能非常重要,”跑步者和健身小工具博主雷·梅克说,他很早就是佳明Forerunner系列产品的粉丝。“其实心脏和腿并不清楚跑步的节奏,”他认为佳明的优势是多功能,但也有可能让休闲运动员望而生畏。

如今佳明的健身设备已不局限于手表,扩展到棒球棒传感器和室内智能自行车训练器等设备,是去年公司主要收入来源。佳明也借此首次突破了2008年创下的35亿美元营收记录,股价也随之飙升。虽然相对健身产品来说,汽车导航市场已经萎缩,航空业务线也成为增速最快的领域之一。

经纪公司罗伯特贝尔德的分析师威尔•鲍尔认为,佳明“攻防有度”是稳步增长的原因。“他们擅长在竞争较少的领域建立强大的防御阵地。”

在某种程度上,尽管佳明的业务已价值数十亿美元,但一直未放弃深耕小众市场。“我们看中佳明的地方在于,他们为目标客户群中提供极为专业的服务,”绘图公司HERE Technologies的首席执行官Edzard Overbeek说,该公司主要为佳明提供位置数据。“负责骑行手表业务的团队本身是专业骑行爱好者。负责航空业务的员工是飞行员。秘诀在于深挖专家用户的需求。”

当然,如果公司只能满足爱好者的需求,发展前景也有限。今年1月的CES电子产品展上,佳明显露了进军大众市场的抱负,展品包括30多块手表和可穿戴设备,从70美元的儿童健身跟踪器到售价2500美元的Marq Driver竞速表,该手表外观时尚,又可为赛车手提供多项功能。统计下来,佳明提供近90款可穿戴产品,为跑步者、游泳者、划船爱好者、飞行员以及只想计步的人们设计。

“最大的挑战在于,让大众市场知道我们这有最适合的手表,”首席营销官苏珊·莱曼表示。“看到人们第一次挑战5公里徒步时或者跑步时手腕空空,我会很难过。”

然而,进驻各个细分市场不可避免要挑战硅谷的巨兽,十年前,正是各家巨头给佳明一记重击。2014年苹果手表在上市时被嘲笑创新性不足,如今已占据智能手表市场38%的份额。即将加入谷歌的Fitbit占据7.5%的份额。对比之下,佳明各款手表市场份额加起来还不到6%。

作为中西部优秀企业代表,佳明淡化了击败强大竞争对手的必要性。“我们并不是想打败苹果,”彭布尔说。“我们只想成为更好的佳明,关注能控制的部分。所以,最重要是做好业务,充分调整业务架构以应对下一次危机。”毕竟,导航设备再精确也无法预知危机的到来。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本刊载于《财富》杂志2020年4月刊,标题为《佳明奔向远方》。

译者:Feb

一直以来,企业投入大量时间和精力寻求创新,然而很多好创意往往来自内部。19世纪,宝洁公司一位化学家认为,漂浮在浴缸中的肥皂能使沐浴体验更欢快,于是研发了象牙肥皂。20世纪70年代,3M一位员工希望阅读赞美诗时更方便标记页面,修改了几年前同事发明但尚未商业化应用的粘合剂;后来便利贴成了3M公司标志性的成功产品。佳明原本是堪萨斯州郊区一家船舶、飞机和汽车导航设备制造商,一群痴迷于跑步的员工将专业知识与爱好结合,在公司急需胜利时助力东山再起。

当时是21世纪初,佳明利用政府的全球定位系统(GPS)技术,在消费设备的小众市场成长了起来。佳明还跟竞争对手TomTom一起主导车内导航设备市场,该款设备也宣告纸质地图时代步入终结。其实佳明慢跑爱好者想起该创意之前,GPS个人健身设备并不受欢迎。“有员工说,‘既然我们的工作本来就跟GPS相关,为什么不为跑步者提供产品呢?”从业31年的佳明首席执行官克里夫•彭布尔回忆道。

2003年,佳明推出了第一款跑步手表,即Forerunner 101。如今,员工发起的产品已发展近20年,在苹果iPhone结合谷歌地图技术抢夺佳明的核心汽车业务后,可穿戴产品的意义显得越发重大。佳明已成为业内罕见远离硅谷的公司,而且受到科技巨头重创后仍能在竞争中蓬勃发展。去年手表和其他可穿戴设备约占38亿美元营收的三分之一。公司估值达150亿美元,虽然跟竞争对手苹果、Alphabet和三星相比微不足道,但在细分市场也是重要的竞争者。

佳明抵御科技行业冲击的方式,是企业坚持擅长领域最好的范例。具体来说,佳明的新产品结合了关键技术即GPS设备,也证明了并不是只有加州北部阳光普照的土地能孕育创新。佳明身上体现出的中西部气质和逆境下的韧性,正是其持久的原因。举个例子,很难想象佳明的大型竞争对手会承认,打进杀手级应用程序的领域或多或少是种幸运。“我们可能低估了可穿戴设备的重要性,”彭布尔说。“当时就是试试水。没人能想到会成长为今天的体量。”

当然,科技巨头仍然会威胁佳明生存,苹果和三星是智能手表的两大巨头,Alphabet旗下的谷歌正收购其竞争对手Fitbit。“向大众销售手表需要不同的产品,思路跟现在(佳明)的做法完全不同。”市场研究机构NPD Group的分析师史蒂芬·贝克说。“能成功做到的企业极少,有勇气去尝试的企业都不多。”

佳明并没有打算征服大众市场,一开始就专为划船运动员、飞行员和越野车爱好者提供小众产品。公司创始人加里·伯瑞尔和高民环之前在Allied Signal担任工程师,1989年创立时GPS还刚刚投入民用。(听起来颇为阳刚的公司名Garmin是二人名字结合)。对爱好者来说,平价导航系统是个意外发现,可以将之前仅供尖端军事装备的技术用在民用设备中。

1991年,佳明发布了首款名叫GPS 100的产品,目标是小型船只和飞机,非常受欢迎,年底公司就已盈利。七年后佳明推出的新产品将数字地图放进车里,也由此蜚声内外。汽车导航“公司开创的产品类别,”彭布尔说,现年54岁的彭布尔是佳明第六位员工。“汽车导航成了公司发展的动力,也让佳明转型消费品牌。”

发展过程中,佳明充分发挥了中西部精神的优势,企业文化非常强调勤奋和谦逊。“他们很清楚如何充分发挥员工的潜能,”前系统工程师约瑟夫•里德说,他经常负责向高级管理层汇报工作。“会表扬,也会批评,”曾在佳明担任市场分析师的斯蒂芬妮·芒顿说:“鼓励员工挑战极限。”

佳明之所以发展稳健,部分原因是内部联系非常严密。去年去世的伯瑞尔是虔诚的基督徒,享年81岁,他自称“服务型领导”,对公司上下的影响如涓涓细流。“他连我妻子和孩子的名字都知道,”2000年至2016年在佳明工作的里克·埃文斯说。“他对每个人都很了解。”

遇到上个10年末的艰难时期,内部团结一致发挥了巨大作用。2007年,佳明推出了汽车、卡车和摩托车约40种车载GPS型号,处于飞速发展时期。汽车导航部门销售额达到23亿美元,同比翻了一番多,占总销售额近74%。然而当年年中苹果发布了iPhone,手机上预装了谷歌地图。iPhone第一个版本并无GPS芯片,主要靠初级技术精确定位位置。但不到一年,苹果手机就整合了GPS,在很多方面可取代佳明的设备。

佳明的业务立即受到冲击,随后的金融危机导致问题更严重。2008年股价暴跌,从2007年超过120美元的高点跌至每股16美元以下。一如华尔街担心,2009年佳明收入下降了5亿美元,降至30亿美元。尽管佳明盈利稳定,当年赚了7.04亿美元,投资者还是很不安。“当时(投资者)都说,‘佳明有可能撑不下去,’”美国银行分析师罗恩•爱泼斯坦表示。

高民环当时担任佳明首席执行官,如今仍担任执行总裁。他保持冷静,将投资重点放在汽车导航之外的业务。举例来说,之后十年佳明收购了全球25家公司,大部分是导航设备分销商,扩大了地理范围,还收购了可访问天气信息以及嵌入可穿戴设备的非接触支付技术。首席执行官彭布尔表示,佳明从未忽视增长的必要性。他说:“最有效的做法就是加倍努力寻求增长和机会。”他说。“省钱和削减开支基本没什么用。”

佳明的产品创新并非完美无缺。2008年,佳明推出了自家的GPS智能手机Nüvifone,使用了谷歌的安卓操作系统。手机零售价为300美元,相当昂贵,触摸屏反应不太灵敏,而且经常分不清用户滑动和点击屏幕的操作。相机质量很差,不能拍摄视频。在该款手机上查看天气、交通和本地活动要交6美元,而在苹果和其他手机上都是免费的。两年半后,佳明退出了智能手机业务。

事实证明,佳明在产品开发方面表现最稳,与硅谷寻求快速发展和突破的风格迥异。不过,这种特质有助于公司进入受监管行业,特别是航空业,因为比起上市时间,航空业更重视精确性。“我曾在苹果公司工作,知道他们行动速度多快,”曾在佳明担任软件工程师的马特·荣格说。“佳明做事的节奏非常不一样。”

说起佳明产品进展缓慢,最有代表性的莫过于健身手表,如今佳明手表逐渐变成希望用GPS技术精确定位的铁杆运动员最爱。“GPS功能非常重要,”跑步者和健身小工具博主雷·梅克说,他很早就是佳明Forerunner系列产品的粉丝。“其实心脏和腿并不清楚跑步的节奏,”他认为佳明的优势是多功能,但也有可能让休闲运动员望而生畏。

如今佳明的健身设备已不局限于手表,扩展到棒球棒传感器和室内智能自行车训练器等设备,是去年公司主要收入来源。佳明也借此首次突破了2008年创下的35亿美元营收记录,股价也随之飙升。虽然相对健身产品来说,汽车导航市场已经萎缩,航空业务线也成为增速最快的领域之一。

经纪公司罗伯特贝尔德的分析师威尔•鲍尔认为,佳明“攻防有度”是稳步增长的原因。“他们擅长在竞争较少的领域建立强大的防御阵地。”

在某种程度上,尽管佳明的业务已价值数十亿美元,但一直未放弃深耕小众市场。“我们看中佳明的地方在于,他们为目标客户群中提供极为专业的服务,”绘图公司HERE Technologies的首席执行官Edzard Overbeek说,该公司主要为佳明提供位置数据。“负责骑行手表业务的团队本身是专业骑行爱好者。负责航空业务的员工是飞行员。秘诀在于深挖专家用户的需求。”

当然,如果公司只能满足爱好者的需求,发展前景也有限。今年1月的CES电子产品展上,佳明显露了进军大众市场的抱负,展品包括30多块手表和可穿戴设备,从70美元的儿童健身跟踪器到售价2500美元的Marq Driver竞速表,该手表外观时尚,又可为赛车手提供多项功能。统计下来,佳明提供近90款可穿戴产品,为跑步者、游泳者、划船爱好者、飞行员以及只想计步的人们设计。

“最大的挑战在于,让大众市场知道我们这有最适合的手表,”首席营销官苏珊·莱曼表示。“看到人们第一次挑战5公里徒步时或者跑步时手腕空空,我会很难过。”

然而,进驻各个细分市场不可避免要挑战硅谷的巨兽,十年前,正是各家巨头给佳明一记重击。2014年苹果手表在上市时被嘲笑创新性不足,如今已占据智能手表市场38%的份额。即将加入谷歌的Fitbit占据7.5%的份额。对比之下,佳明各款手表市场份额加起来还不到6%。

作为中西部优秀企业代表,佳明淡化了击败强大竞争对手的必要性。“我们并不是想打败苹果,”彭布尔说。“我们只想成为更好的佳明,关注能控制的部分。所以,最重要是做好业务,充分调整业务架构以应对下一次危机。”毕竟,导航设备再精确也无法预知危机的到来。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本刊载于《财富》杂志2020年4月刊,标题为《佳明奔向远方》。

译者:Feb

For all the time, effort, and money companies plow into the endless hunt for innovation, many of their best ideas come from within. A Procter & Gamblechemist in the 19th century figured a bar of soap that floated in the tub would enliven the bathing experience, and Ivory Soap was born. In the 1970s, a 3Memployee, craving a better way to mark pages in his hymnal, modified an uncommercialized adhesive invented a few years earlier by a colleague; Post-it Notes became an iconic 3M success story. And at Garmin, a suburban Kansas City maker of navigational devices for boats, planes, and cars, a group of running-obsessed employees applied their know-how to their hobby—a move that revitalized the company when it badly needed a win.

It was the early 2000s, and Garmin had grown from its niche of making consumer devices utilizing the government’s global positioning system, or GPS, technology. Together with rival TomTom, Garmin dominated the market for in-car navigational devices, game-changing gadgets that marked the beginning of the end for foldable maps. GPS for personal fitness wasn’t popular before the Garmin jogging klatch began noodling. “They said, ‘We do all these GPS things. Why don’t we have a GPS product for runners?’ ” recalls Cliff Pemble, Garmin’s CEO and a 31-year company veteran.

In 2003, Garmin offered its first fitness wearable, the Forerunner 101. What began as an employee side project has come to define the company nearly two decades on—especially after a lethal technology combination of the iPhone and Google Maps laid waste to Garmin’s core automotive business. Today, Garmin is a rare example of a company far from Silicon Valley that not only took a punch from the tech behemoths but has thrived in competition with them. Watches and other wearables made up about a third of Garmin’s $3.8 billion in revenue last year. It sports a $15 billion valuation, making it a minnow compared with rivals Apple, Alphabet, and Samsung—but a substantial player in its own right.

How Garmin withstood the onslaught is a case study of a company sticking to what it knows best—in its case, products pegged to one key technology, GPS devices—and proof that not all innovation comes from a sun-kissed strip of land in Northern California. Indeed, Garmin’s aw-shucks Midwestern nature and its stick-to-itiveness in the face of adversity go a long way in explaining its staying power. It’s hard to imagine the company’s mega-cap rivals acknowledging, for example, that they more or less lucked into what would become a killer app. “What we probably underestimated was the importance of the wearables,” says Pemble. “We were dabbling with it way back when. But nobody could foresee that it would become the category that it is today.”

The big tech companies remain an existential threat for Garmin, of course. Apple and Samsung are the two biggest players in smartwatches, and Alphabet’s Google is in the process of buying rival Fitbit. “Selling the watch to the masses requires a different product and a whole different mindset than what [Garmin is] doing today,” says ¬Stephen Baker, an analyst with market researcher NPD Group. “There aren’t a lot of instances where companies have been able or even tried to make those kinds of leaps.”

Garmin didn’t set out to conquer mass markets, focusing instead from the beginning on niche products for enthusiasts like boaters, pilots, and off-roaders. Its founders, Gary Burrell and Min Kao, were engineers at Allied Signal who started the company in 1989, shortly after GPS became available for civilian use. (The muscular-sounding Garmin is simply a mashup of the duo’s given names.) Affordable navigation systems were a revelation for hobbyists, giving them access to the same technology previously reserved for users of sophisticated military equipment.

The company released its first product, the unglamorously named GPS 100, in 1991. It targeted small boats and planes, and it was so popular that by the end of the year, Garmin was profitable. Seven years later it would introduce the product that didn’t just put Garmin on the map, it put digital maps in people’s cars. In-car navigation “was a category that we pioneered,” says Pemble, who is 54 and was Garmin’s sixth employee. “That gave us rocket fuel. It made Garmin a consumer brand.”

Along the way, Garmin played to its Midwestern strengths of stressing a corporate culture based on hard work and humility. “They knew how to get the best out of people,” says Josef Reed, a former systems engineer often tasked with briefing senior management. “They’d give praise and critiques at the same time.” Says Stephanie Mountain, a former Garmin marketing analyst: “They were constantly pushing people to their limits.”

The company had permission to push, in part, because it was so tight-knit. Burrell, a devout Christian who died last year at age 81, referred to himself as a “servant leader,” and his presence was felt throughout the company. “He literally knew my wife and kids’ names,” says Rick Evans, who worked for Garmin from 2000 to 2016. “And he knew that about everybody.”

Such tightness would come in handy when times got tough in the late 2000s. The company was soaring in 2007, when it had some 40 different in-car GPS models for cars, trucks, and motorcycles. The automotive segment had become a $2.3 billion business, more than doubling its revenue from the previous year and representing nearly 74% of overall sales. Then came the iPhone, which Apple released in the middle of that year with Google Maps loaded on all phones. The first version of the iPhone lacked a GPS chip, relying instead on more rudimentary technology to pinpoint locations. But within a year, Apple incorporated GPS, making its phone a multifaceted replacement for Garmin’s stand-alone devices.

Garmin’s business took an almost immediate hit, and its problems were exacerbated by the financial crisis. In 2008, the stock price collapsed, falling below $16 a share from highs of more than $120 in 2007. As Wall Street had feared, revenue declined by $500 million in 2009, to $3 billion. Though Garmin remained solidly profitable—it earned $704 million that year—investors were rattled. “Back then, [investors] would come in and say, ‘They’re going to get put out of business,’ ” says Ron Epstein, a Bank of America analyst who has covered Garmin for 15 years.

Kao, who remains Garmin’s executive chairman and was CEO at the time, kept calm and focused investments on the nonautomotive parts of the company’s business. Over the next decade, for example, Garmin bought more than 25 companies around the world, mostly distributors of navigation equipment that broadened its geographic reach. It also bought access to weather information as well as contactless payments technology it would embed in its wearable devices. Pemble, the CEO, says Garmin never lost sight of the need to grow. “The most efficient thing to try is to double down on growth and opportunity,” he says. “Saving money and cutting expenses never really works.”

Garmin’s product innovation was hardly flawless. In 2008 it debuted the Nüvifone, its own GPS-enabled smartphone that eventually used Google’s Android mobile operating system. Expensive for its day at $300 retail, the phone had a touch screen that wasn’t very responsive and often confused swiping and tapping. Its camera was low-quality and didn’t include video. And Garmin charged users $6 to check the weather, traffic, and local events—things Apple and other phonemakers offered for free. The company exited the smartphone business after two and a half years.

Garmin proved to be at its best when it plodded along at product development, the antithesis of Silicon Valley’s mantra of moving fast and breaking things. It helped that the company made products for regulated industries, particularly aviation, where precision is more important than time-to-market. “I had worked for Apple and seen how quickly they could move,” says Matt Ronge, a former Garmin software engineer. “Seeing the pace at which things moved at Garmin was very different.”

Nowhere was the company’s slow progress more apparent than in fitness watches, which gradually became favorites of hard-core athletes eager to use GPS to pinpoint the accuracy of their events. “Having the GPS is so important,” says Ray Maker, a runner and fitness gadget blogger, who was an early convert to Garmin’s Forerunner line. “Your heart and legs don’t really know what pace you’re doing.” He says Garmin’s strength is its multiple features, which may also be intimidating for casual athletes.

Garmin’s fitness segment, which extends beyond watches and into devices like a baseball bat–swing sensor and indoor smart bike trainers, was the company’s top revenue generator last year. That helped the company surpass its 2008 revenue mark of $3.5 billion for the first time, sending its shares soaring as well. While the automotive segment has shriveled relative to its fitness offerings, its aviation line has become one of its fastest growers.

Will Power, an analyst with brokerage Robert W. Baird, credits Garmin’s “blocking and tackling” for its staying power. “They build really strong defensive positions in areas that, by and large, have less competition.”

In a way, Garmin never stopped being a niche player, albeit a multibillion-dollar one. “What we like about Garmin is the way they position deep expertise around the customer group they’re serving,” says Edzard Overbeek, CEO of HERE Technologies, a mapping company that provides location data to Garmin. “The team that is responsible for their cycling watch are professional cyclers. The aviation team are pilots. The secret sauce is understanding what the expert user wants.”

A company can go only so far catering to enthusiasts, of course, and at the CES gadgets show in January, Garmin showed off its mass-market aspirations around fitness products—displaying more than 30 watches and wearables ranging from a $70 kids’ fitness tracker to a $2,500 Marq Driver watch that boasts a stylish look and multiple motor-sport functions. In all, Garmin offers about 90 wearable products made for runners, swimmers, boaters, pilots, and people who just want to track their steps.

“The biggest challenge is getting that mass market to understand we have the perfect watch for them,” says Susan Lyman, the company’s top marketing executive. “It kills me when I see people walking their first 5K or running with nothing on their wrist.”

Going after every segment inevitably means challenging the beasts of Silicon Valley, the same companies that knocked Garmin off its perch a decade ago. The Apple Watch, mocked as a less-than-innovative offering when it debuted in 2014, now commands 38% of the smartwatch market. Fitbit, soon to be part of Google, has 7.5% share. All of Garmin’s watches combined add up to just under 6%.

Garmin, ever the good Midwesterner, plays down the necessity of beating the unbeatable competitor. “We’re not trying to out-Apple Apple,” says Pemble. “We’re trying to be Garmin. We only focus on what we can control. So we prepare our business and structure our business in a way that best suits it for the next crisis.” After all, you don’t need a fancy navigational device to know that crisis eventually will arrive.

A version of this article appears in the April 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline "Garmin Goes the Distance."