|

你可能还记得,几年前在订阅的新闻推送上见过Facebook发布类似以下内容的帖子: “今天,2014年11月30日,为了回应Facebook的准则,遵循知识产权准则第L.111、112和113条的规定,本人特此声明,个人信息页面发布的个人数据、制图、绘画、照片、文本内容等均属本人版权所有。无论何时,若要以商业用途使用相关内容,都需征得本人书面同意……侵犯本人隐私将受到法律(UCC 1 1-308 – 308 1 – 103和罗马规约)惩处。” 其实这些内容都是乱写而已。事实上,国际刑事法院的所谓罗马规约仅涉及违反人道的罪行,与Facebook的用户政策无关。但这种杜撰帖盛行却在提醒我们,近来删除Facebook运动的源头其实比想象中深远得多。 在Facebook成长为社交媒体巨头的漫长道路上,经常会出现被大肆炒作的“Facebook杀手”,号称新平台可提供取代Facebook,而且规则比Facebook更好。第一个是Diaspora,起初是一家流行的众筹活动,旨在打造由用户掌控的去中心化非营利平台,从而取代Facebook。Facebook创始人马克·扎克伯格甚至还参与了Diaspora的众筹。这说明他把Diaspora视为一个有趣的实验。2016年出现一家名叫Ello的社交网络,宣传口号是:“Facebook真正的使命不是让你快乐。他们不关心你跟老朋友联系,也没想着促进有趣的对话。你(Facebook的卑微用户)不是客户……(个人信息)数据的买家才是客户,Facebook的业务就是围绕他们来的。”这种宣传词当时很有吸引力,Ello的创始人称,一小时内有3.1万人注册。(但此后这些用户又都弃之而去,只是宣传得好听产品难用还是不行。) 你可能还是支持Facebook测试民主化时表示支持的百万用户之一。2012年,Facebook给用户投票决定修改隐私政策的机会,但还是耍了一点心机:要让投票结果生效,参与投票的Facebook用户必须达到用户总数的30%。据美国有线电视新闻网(CNN)当时报道:“投票差点成功修改Facebook的政策,也就差了2.99亿票。” 这些都是事情发展到当前局面的序曲。在大数据公司剑桥分析(Cambridge Analytica)导致的丑闻事件中,我们发现针对Facebook平台已出现更广泛的政治意识。所有用户都面临的机会不仅可以“争取到”Facebook暂时的妥协,还能借机重新构想我们进入平台时签订的社会(也有财务与政治方面的)协议。 早年间互联网先驱们的梦想是建立天然可自由驰骋的网络天堂,然而人们感觉现实却是一个个参与式农场,少数大平台圈地围栏,每天各自埋头收获数十亿用户活动产生的收益。这么做是有代价的。2017年英国《卫报》做的一项调查显示,认为Facebook对世界有益的美国人不到受访者总数的三分之一,仅有26%的受访者认为Facebook关心用户。 那么,现在我们要回答的重要问题就是:现状从结构上可能如何改变?如何才能创造新的模式,不仅能发挥Facebook标榜的所谓“分享的力量”,真正分享价值和治理决策,同时提供更大的透明度和自由度? 理想化的“合作型平台” 美国科罗拉多大学博尔得分校传媒研究助理教授内森·施耐德目前领导一项仅限于学术界但正在兴起的运动。其主张民主运营并协作管理大量重新构想的技术平台,即“合作型平台”,不再是农场和工厂。该运动希望将圈起用户的农场变成数字化的集体农庄。 施耐德提到了一些传统行业沿用的类似方法。比如英国连锁百货商店约翰·刘易斯早在1929年就成立了员工所有的信托,让员工分享公司的盈利,挑选管理董事会的代表。施耐德认为,对有影响力的新平台来说,不能只是让拿到薪水的员工分享平台创造的价值,享有重大决策发言权、成为平台管理代表,数百万的平台用户也应享有权力。他提议Twitter的用户设法回购公司,认为只有当Twitter归用户所有才能发挥公共功能。在他看来,Twitter之所以面对诸多挑战,问题不是没有为用户服务,一些发端于Twitter的正义行动可以证明。他认为,主要原因在于“华尔街的生意经变成了Twitter的经营之道。” 施耐德等人倡导的买下Twitter运动影响力惊人。最终还变成提交Twitter公司2017年年度大会的五项提案之一。该案例也说明,Twitter确实有机会发挥完全不一样的作用。 如果Twitter归用户共同拥有,可能会发觉新的可靠收入源,因为用户会有主人翁意识,Twitter的成败与大家都有关。我们不会让Twitter背负短期的股市压力,从而实现平台的潜在价值。这正是Twitter管理层遵循当前商业模式竭力奋斗多年却做不到的。我们可以制定更透明、更有问责效力的规定应付隐私信息滥用问题,可能为了激励创新重新开放Twitter的数据。总之,我们会为了Twitter的经营成功和可持续发展全力以赴。用户与Twitter的交流也可确保现有投资者获得更公平的回报,不用再想别的法子。 Twitter公司并没有接受这一提议。Twitter也很难走向合作型平台的道路。但起码提出了一个很有说服力的发展前景,今后用户有了期待,下一代平台缔造者也有了努力方向。 实际上,现在已开始出现采用合作经营理念和商业模式的公司。合作型图片分享平台Stocksy将摄影师和电影制片人聚集在一起,可授权他人使用自己作品。他们通过平台合作无间,也形成一个数百万美元的庞大产业。正如Stocksy所说的:“(给艺术家多一些尊重和支持,少一些虚名。)我们相信可以用创造性的方式保证诚信,可以公平分享盈利,共同拥有知识产权,每一种声音都被听见。” 要帮助合作型平台和类似创意成功,政府要确保这类企业更容易融资从而扩大规模,无需依靠大投资者和传统的资本市场募资。而且,要让这类商业模式走出小作坊变成主流,在模式设计层面也是真正的挑战。一旦攻克技术难题,无论是在道德还是在财务角度看,对用户和内容生产者都有吸引力。特别是考虑到Facebook与用户的关系越来越紧张,一个用户体验类似,合作协议却更公平的竞争对手有望轻易吸引叛逃Facebook的用户。 平台的多种发展道路 十年前,万维网之父蒂姆·伯纳斯-李就看出了Facebook之类参与式农场兴起的危险。 2008年,设计互联网将近二十年后,李呼吁打造“去中心化的社交网络”,要从越来越中心化的网站手中夺回深爱的互联网。他很看好流动性更强、更多元化的平台,即“不会受到审查、垄断、监管和其他中央集权机构影响的线上社交网络。” 现在,李正努力开发解决该问题的项目,制定大刀阔斧革新互联网应用运作方式的方案。该方案会将用户所有的个人数据和内容从应用和平台中剥离,目前都存放在应用和平台上。李的Solid项目将让用户拥有自己的数据,纳入个人安全“豆荚”(pod),我们上网时自己带着。想想一下,不用再把个人数据放在第三方平台上,而是自己掌握(这就是极客们所说的互通性)。我们可以携带照片、好友信息、过往身体健康记录、旅行地图、购物清单,甚至在不同平台上的声望——这也是一笔重要财富。我们可以自由决定授权哪些人接触自己的数据,以及如何使用。Solid不只是一种新技术,更像一种思想体系。按照Solid的设想,个人数据会向本人汇报。 还有个解决方案就是时下热门的技术区块链。区块链是一种分布式公开账本,所有人都可以在上面记录并查看交易。和目前银行主要采用的中心化私密账本不同,区块链是透明公开的。在区块链中,确认交易的不是中央控制,而是分布式的流程。有些人可能已经通过目前最有名的区块链应用有所了解,因为虚拟货币比特币就是建立在区块链技术之上。 如果并非技术人士,其实很难理解区块链运作的方式,即使花上几小时研究。但最重要的是,要明白该技术有望应用于人类社会。正如英国杂志《经济学人》所说:“区块链给彼此不认识或者不信任的人提供了一种方法,记录下所有者信息,而且所有相关人士都要知晓。这是一种创造并维护真相的方法。” 区块链的潜力巨大,热度也非常高。(不过,和其他所有技术一样,区块链很容易被吸收和利用)。区块链开启了新世界的大门。在理想世界中,用户可能无需任何中间商直接交易。很容易就能想到,可以利用区块链进行房地产合约或者金融交易。届时人们还让用户、司机、驾驶者、房东和租客都摆脱现在的超级平台Facebook、Uber和Airbnb,直接合作和交易。 展望未来,对关于下一代参与型技术和创意如何改变生活的预测非常多。无论是虚拟现实、增强现实,还是区块链,我们今天所知的平台最终都可能过时。不管以后怎么变化,我们要制定并坚持原则,保证世界上少一些垄断独占,多一些公开透明,具有的能力要与影响程度匹配。 符合公众利益的算法 为了重新设计Facebook之类平台,算法也要改造。Facebook已经显示,社交媒体网站对改变消费者的偏好、激发或者阻挠极端主义作用极大,区区几行代码就可以左右用户情绪。但现在,Facebook的算法正秘密地为私人利益服务。 想象下一种符合公众利益的算法,该如何发挥作用。假如有一种方案能满足所有平台参与者和全社会的利益,不再只为平台所有者、广告商和投资者牟利,应该什么样? 应该需要具备三大特征。第一,由于输入算法的内容将决定我们看到什么样的内容以及哪些优先呈现,就应该用户透明公开,包括平台根据什么标准和谐攻击性的内容或者有仇恨情绪的言论。第二,所有用户都应有一系列调整工具改变接触到的世界,可以主动了解先前不认同的内容,也可以“筛选”圈子之外的观点看法,还可选择少看耸人听闻消息。 第三,算法的默认设置要经过测试,确认符合公众利益,要考虑平台怎样更好地服务于社会。这种操作可能像升级版的公共广播,要呈现经过筛选的内容减少社会紧张局势和极端主义,增进公民协商,推动多元化发展,给缺乏服务需求急迫的弱势群体发声机会。只有经历一系列挑战,算法才能相对成熟。合理争论包括平台是否发挥“决定作用”,怎样影响以及应该发挥多大影响。从道德层面来看,后续挑战的难度比设计算法的挑战更大。 为了推动此类解决方案,作为参与式农场里的用户,我们更需要行动起来,而不是哀叹命运。要重新协商我们参与的协议,将需要技术人士、企业家、平台自身和所有用户真正投入并付出努力。 删除Facebook账号运动只是开始。我们要更进一步。未来几个月,可能会有改革Facebook、监管Facebook,甚至取代Facebook的运动出现。(财富中文网) 亨利·提姆斯是92nd Street Y执行董事。本文改编自杰瑞米·海曼斯和亨利·提姆斯合著的《新势力》一书。 译者:Pessy 审校:夏林 |

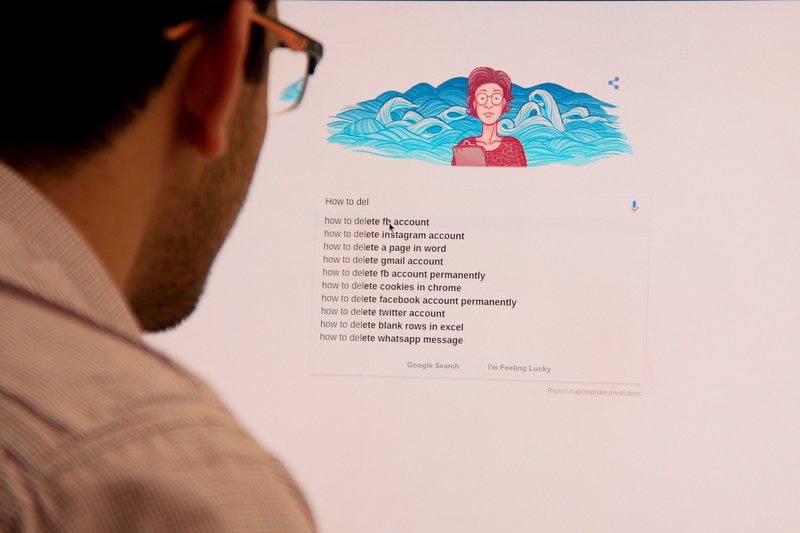

A few years ago, you may remember seeing Facebook posts like this dotting your newsfeed. “Today, November 30, 2014 in response to the Facebook guidelines and under articles L.111, 112 and 113 of the code of intellectual property, I declare that my rights are attached to all my personal data, drawings, paintings, photos, texts etc… published on my profile. For commercial use of the foregoing my written consent is required at all times… The violation of my privacy is punished by the law (UCC 1 1-308 – 308 1 – 103 and the Rome Statute).” The posts were based on an urban myth. The Rome Statute in fact covers crimes against humanity, not Facebook’s relationship with its users. But the popularity of such posts remind us that the #DeleteFacebook movement we have seen in recent days has much deeper roots. Every now and then on Facebook’s long journey to platform hegemony, a much-hyped “Facebook Killer” has come along—a new platform that might provide a viable alternative, built on better principles. First there was “Diaspora,” which began as a viral crowd-funding campaign to create a non-profit, user-owned, decentralized alternative to Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg even chipped in—a solid indication that he regarded Diaspora as little more than a charming experiment. Then, in 2016, the social network Ello came to life with a powerful sales pitch: “Facebook’s real mission isn’t to make you happy. It isn’t to connect you with old friends, or to facilitate interesting conversations. You (the humble Facebook user) are not the customer … The people who buy [your] data are the real customers, and that’s to whom Facebook’s business is oriented.” This promise was seductive enough that at one point, its founder claimed that 31,000 people an hour were signing up to the new platform. (Though in time, these users fell away, with the clunky product not living up to the sexy hype.) You might even have been one of the less than a million users who took part in Facebook’s attempt at direct democracy on the platform. In 2012, it offered users the chance to vote to ratify changes to its privacy policy, but there was one catch: For the vote to be binding, 30% of Facebook users had to participate. As CNN put it at the time: “Voting closes on Facebook policy changes, only 299 million votes short.” These are all preludes to the current moment. What we are seeing, in light of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, is the emergence of a much broader political consciousness in regards to the platform. This opportunity ahead is for all of us users not simply to “win” occasional concessions from Facebook, but to start to re-imagine the social (and financial and political) contract that we have entered into with the platform. Far from the organic, free-roaming paradise the early Internet pioneers imagined, there is a growing sense that we are now living in a world of participation farms, where a small number of big platforms have fenced, and harvest for their own gain, the daily activities of billions. This has a real price. In a Guardian poll in 2017, less than one-third of Americans agreed that Facebook was good for the world, and a paltry 26% believed that Facebook cared about its users. So the big question ahead is: How might things be structurally different? How might we create models that don’t merely offer the vanilla “power to share” that Facebook touts, but actually share value and governance decisions, along with delivering greater transparency and freedom? The promise of “platform co-ops” The University of Colorado Boulder’s Nathan Schneider is one of the leaders of a growing (but still quite academic) movement that is championing what he calls “platform co-ops,” democratically run and governed cooperatives reimagined for a world of peer-based technology platforms, not just farms and factories. This movement wants to turn the participation farm into something that looks more like a digital kibbutz. Schneider points to models in more traditional industries that run along these lines, like the U.K. department store chain John Lewis, which in 1929 was put into a trust owned by its employees, who share in the retail chain’s profits and elect representatives to its governing board. For new power platforms, he argues, it is their millions of users, not just those on the payroll, who should share in the value created, have a say in big decisions, and be represented in the governance of these platforms. He has proposed that Twitter’s users try to buy it back, arguing that it serves an essential public function. In his mind, for all its challenges, the problem isn’t that Twitter isn’t working for its users—he cites the powerful justice movements that rely on it as evidence that it is. The problem is that “Wall Street’s economy has become Twitter’s economy.” The #BuyTwitter movement championed by Schneider and others was significant enough that it ended up as one of the five proposals on the table at Twitter’s 2017 annual general meeting. It made a strong case for a Twitter that would function very differently. A community-owned Twitter could result in new and reliable revenue streams, since we, as users, could buy in as co-owners, with a stake in the platform’s success. Without the short-term pressure of the stock markets, we can realize Twitter’s potential value, which the current business model has struggled to do for many years. We could set more transparent, accountable rules for handling abuse. We could re-open the platform’s data to spur innovation. Overall, we’d all be invested in Twitter’s success and sustainability. Such a conversion could also ensure a fairer return for the company’s existing investors than other options. This motion was not embraced by Twitter Inc. And it would be very tough to flip Twitter into a co-op in this way. But it points to a compelling alternative vision, for us as participants and for the next generation of platform creators. In fact, companies with this cooperative-inspired philosophy and model are beginning to emerge. The photo-sharing co-op Stocksy brings together photographers and filmmakers, giving them an opportunity to license their work. They are a proud platform co-op but also a serious and growing multimillion-dollar business. As they put it: “(Think more artist respect and support, less patchouli.) We believe in creative integrity, fair profit sharing, and co-ownership, with every voice being heard.” For platform co-ops and similar ideas to succeed, governments will have to make it easier to raise money to scale without relying on big investors or the traditional capital markets. There is also a real engineering challenge in ensuring that these types of models move beyond the artisanal to the mainstream. But if the technical piece can be cracked, it’s not hard to see the moral (and financial) appeal to users and content creators. Especially given Facebook’s increasingly strained relationship with its users, a rival that offered a similar user experience but a much fairer deal, might easily attract defectors. Free-range platforms A decade ago, none other than the father of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, saw the dangers of participation farms like Facebook looming. In 2008, almost 20 years after laying out his original vision, he rallied for the building of “decentralized social networks” that would reclaim his beloved web from increasingly centralizing sites. He saw a big prize in a more fluid and pluralistic world of platforms in which “online social networking will be more immune to censorship, monopoly, regulation, and other exercise of central authority.” Today, he is hard at work on a project to address that very issue, a plan to radically alter the way web applications work, one that would divorce all our personal data and content from the apps and platforms that now—often literally—own it. Berners-Lee’s Solid project would allow us to own our own data as part of a personal secure “pod” in which we would carry around our digital lives. So imagine that, rather than having all your data on a third-party platform, you now take it with you. (This is what geeks call “interoperability.”) You walk around with your photos, friends, health histories, a map of all the places you have traveled, a list of all your purchases—even the online reputation you have built up in various platforms, an especially powerful commodity. You are liberated to decide what access you would like to grant—and on what terms—to whom. Solid is much more than a different kind of technology; it is a different philosophy. With Solid, your data “reports to you.” Another solution to the same problem comes in the great—and much-hyped—hope of the Blockchain. The Blockchain is a distributed public ledger that allows everyone to record and see what transactions have taken place. Unlike a centralized secret ledger—such as those of banks—it is transparent. And transactions are verified not by a central force, but as a distributed process. You might know the Blockchain from its most famous (and controversial) application to date: It is the underlying technology upon which the virtual currency Bitcoin is built on. For non-technologists—even those who have spent hours trying to get their heads around this—the way this actually works can be hard to grasp. But the most important things to understand are the potential human applications. As The Economist puts it, “It offers a way for people who do not know or trust each other to create a record of who owns what that will compel the assent of everyone concerned. It is a way of making and preserving truths.” The potential of this is as huge as the hype (although, like all technologies, Blockchain remains vulnerable to co-optation and capture). It opens up a world where users might exchange value directly without an extractive middleman. We can easily imagine real estate contracts or financial transactions living on the Blockchain. But we might imagine, too, the intermediaries being removed from the mega-platforms of the world—our Facebooks, Ubers, or Airbnbs—when users, drivers, and riders, or hosts and guests, work out ways to collaborate and exchange directly with each other. As we look to the future, there is no shortage of predictions about the next participatory technologies and ideas that will transform our lives. Whether it be virtual reality, augmented reality, or blockchains, platforms as we know them today will likely end up feeling rather quaint. But however things turn out, we need to cling to, and build for, a set of principles that ensure the worlds we will live in are less monopolistic, more transparent, and much more attuned to their broader impact. A public-interest algorithm To truly reimagine a platform like Facebook, we need to reimagine its algorithm. As Facebook has shown us, social media sites have huge power to alter our consumer preferences, spur or hinder extremism, and sway our emotions with tweaks of code. But today their algorithms function as secret recipes that serve private interests. So let’s consider how a “public interest algorithm” might work instead. What might a formula designed to favor the interests of platform participants and society at large—instead of just their owners, advertisers, and investors—look like? It would need three key features. First, the inputs into the algorithm, which shape what content we see and what gets priority, would be fully transparent to the user, including the criteria used by the platform to moderate offensive content or hate speech. Second, every user would have a range of dials that allowed them to alter their world. They could choose to engage with more content they disagreed with. They could “filter in” perspectives and views from those well outside their bubbles. They could reduce sensationalism. Third, the default settings of the algorithm would apply a public interest test, considering how the platform can better serve our broader society. This might operate like an updated version of public broadcasting, bringing to the surface content proven to reduce social tension and extremism and bolster civic discourse, promoting pluralism, and showcasing unserved and underserved communities. This would not come without its challenges—legitimate debates would need to be had around whether, how, and how much a platform should “tip the scales” in this way—but it is a greater moral challenge than an engineering one. To advance solutions like these, we, as the participants on the participation farms, need to do more than just lament our fates. It will take inspired and dedicated effort—by technologists, entrepreneurs, the platforms themselves, and all of us—to renegotiate the contract with which we participate. #DeleteFacebook is just the start. We need to go deeper. In the coming months, we may see #ReformFacebook, #RegulateFacebook, and even #ReplaceFacebook take off. Henry Timms is executive director of 92nd Street Y. This article was adapted from the book NEW POWER by Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms. |