肖恩·李是位于美国西雅图的一所高中的社会研究教师,他认为在21世纪,网民也有必要像司机考驾照一样,接受必要的互联网教育,因为这已经成了现代生活的必需品。

肖恩·李已经把这种教育带到了课堂上,他会教学生如何核实网络信息的真伪,让新闻的来源多样化,并且用批判性思维看待网络内容。他还成立了一个组织,方便其他教师进行资源共享。

“互联网是一项新兴技术,没有人教过我们如何正确地使用它。所以有人会说:‘我们对此无能为力’,然后就举手投降了。而我不这么想,我认为公众可以不必被算法所左右。”

网络虚假信息已经成为了一个社会毒瘤,这一点从新冠疫情期间的种种乱象和美国的历次选举中都不难看出。有越来越多的教育工作者和研究人士都致力于解决这个问题。到目前为止,美国在这方面已经落后于不少国家,由此产生的恶果也是明显的。

考虑到教师在课堂上要教的东西已经很多了,如何把网络素质融入课堂,这也是一个不小的挑战——尤其是在美国,疫苗、公共卫生、投票、气候变化和俄乌冲突等问题既是虚假信息的高发地,也是高度政治化和敏感的问题。肖恩·李的组织最近一次聚会的讨论主题就是:“如何在不会被解雇的情况下谈论阴谋论”。

在美国密苏里州韦伯斯特格罗夫斯的韦伯斯特大学(Webster University)任教的媒体素养专家朱莉·史密斯指出:“重点不是要教大家思考什么,而是要教大家如何思考,要让你的大脑参与进来,让你去想:‘这个消息是谁创建的?为什么?为什么现在我会看到它?它让我产生了什么感觉?这又是为什么?’”

很多人认为,打击网络虚假信息最好的方法,就是对这个问题立法,并且改变现有的推荐算法。一些科技公司也在研究自己对虚假信息问题的解决方案。

但是,教大家如何识别网络虚假信息,或许才是最为有效的方法。比如最近,美国新泽西州、伊利诺伊州和得克萨斯州等地的学校都实施了新的网络素养授课标准,教学内容相当广泛,涉及互联网与社交媒体的运营方式,如何通过不同的消息来源识别虚假信息,以及对断章取义的消息和高度情绪化的标题保持警惕,等等。

美国的媒体素养课程通常被包含在历史、政府或者其他社会研究课程之中,学生一般会在高中阶段接触到这些课程。不过专家认为,任何年龄段的网民进行相关学习都是非常有益的。

例如,按照芬兰政府的反虚假信息计划,芬兰儿童从幼儿园开始就会接触到互联网的有关知识,这也是为了“从娃娃抓起”提高全民的反虚假宣传意识。

芬兰科学与文化部的部长佩特里·洪科宁近日在接受采访时表示:“在网络时代之前,媒体素养是我们最关注的问题之一。重点是培养人们的批判性思维,这是每个人越来越需要的技能。我们必须以某种方式保护人民、捍卫民主。”

洪科宁在今年年初访问华盛顿期间曾经接受美联社(The Associated Press)的专访,此访期间,他也在相关会议上讨论了芬兰打击网上虚假信息的工作。芬兰在近期的一份西方民主国家媒体素养工作报告中被排在榜首,加拿大被排在第7名,而美国排在第18名。

在芬兰,这些课程并非只是面向小学生。政府部门还会向国民发布提醒,告诉大家如何避免虚假网络信息和通过多个来源核实新闻真伪。另外,芬兰还有一些针对老年人的项目,因为与年轻网民相比,足不出户的老年网民更容易受到虚假信息的伤害。

在美国,有些尝试开设网络素养课程的学校甚至遭到了以政治为理由的反对,有人将这种课程等同于“思想控制”。肖恩·李称,由于这种担忧,很多老师甚至不敢尝试讲这样的课。

从几年前开始,华盛顿大学(University of Washington)发起了“警惕虚假信息日”(MisinfoDay)活动,他们将高中生们组织起来,以媒体素养为主题,开展为期一天的演讲、练习等主题活动。今年,华盛顿大学也举办了三场“警惕虚假信息日”主题活动,共吸引了全州的700名学生参加。

活动的发起者、华盛顿大学的教授杰文·韦斯特表示,他听说其他州甚至澳大利亚的一些教育工作者也有兴趣举办类似的活动。

韦斯特称:“也许终有一天,全美国都会有一个专门的日子来提醒人们关注媒体素养。在对抗虚假信息方面,我们有很多事情可以做,比如在监管、技术和研究上,但没有什么事情是比提高我们自身的识别能力更重要的了。”

对于疲于应对各种教学任务的老师们来说,媒体素养只是又增加了一项教学任务而已。但居住在马萨诸塞州的一位母亲艾琳·麦克尼尔认为,在未来的经济中,这项技能与计算机工程和软件编程同样重要。为此,麦克尼尔创办了一家名叫Media Literacy Now的全国性非盈利机构,倡导开展数字素养教育。

她说:“这是一个创新问题。数字化通信是信息经济的基础,而如果我们不解决好虚假信息的问题,就将对我们的经济产生巨大影响。”

在我们与媒体素养专家交流时,他们经常会拿考驾照的例子来打比方。汽车早在20世纪初就已经投产,并且很快普及开来。但直到近30年后,世界上才有了第一个针对驾驶技能的课程。

那么,究竟是哪些改变催生了驾驶课程呢?首先是政府通过了规范车辆安全和驾驶员行为的法律,其次是汽车公司增加了转向柱、安全带和安全气囊等功能。于是在20世纪30年代中期,道路交通安全的倡导者开始推动强制性的驾驶技能教育。

很多虚假信息和媒体素质的研究人士认为,在对抗虚假信息上,政府、行业和教育界应当各司其职,做到有机结合,而且任何应对网络虚假信息的有效解决方案,都必须包含教育因素。

加拿大的学校早在几十年前就开设了媒体素养课程,一开始它主要教学生如何识别电视中的虚假信息,后来随着时代发展,扩展到了数字时代。加拿大媒体素养组织MediaSmarts的教育主管马修·约翰逊表示,现在媒体素养已经被公认为是学生的一项重要素质。

他说:“在公路上,我们需要限速,也需要精心设计的公路和良好的监管来确保行车安全。但同时我们也要教人们怎样安全驾驶。而在虚假信息的问题上,不管监管机构怎样做,也不管各大平台怎样做,各种内容总会出现在网民眼前,所以他们需要有工具来批判性地对待它。”(财富中文网)

译者:朴成奎

肖恩·李是位于美国西雅图的一所高中的社会研究教师,他认为在21世纪,网民也有必要像司机考驾照一样,接受必要的互联网教育,因为这已经成了现代生活的必需品。

肖恩·李已经把这种教育带到了课堂上,他会教学生如何核实网络信息的真伪,让新闻的来源多样化,并且用批判性思维看待网络内容。他还成立了一个组织,方便其他教师进行资源共享。

“互联网是一项新兴技术,没有人教过我们如何正确地使用它。所以有人会说:‘我们对此无能为力’,然后就举手投降了。而我不这么想,我认为公众可以不必被算法所左右。”

网络虚假信息已经成为了一个社会毒瘤,这一点从新冠疫情期间的种种乱象和美国的历次选举中都不难看出。有越来越多的教育工作者和研究人士都致力于解决这个问题。到目前为止,美国在这方面已经落后于不少国家,由此产生的恶果也是明显的。

考虑到教师在课堂上要教的东西已经很多了,如何把网络素质融入课堂,这也是一个不小的挑战——尤其是在美国,疫苗、公共卫生、投票、气候变化和俄乌冲突等问题既是虚假信息的高发地,也是高度政治化和敏感的问题。肖恩·李的组织最近一次聚会的讨论主题就是:“如何在不会被解雇的情况下谈论阴谋论”。

在美国密苏里州韦伯斯特格罗夫斯的韦伯斯特大学(Webster University)任教的媒体素养专家朱莉·史密斯指出:“重点不是要教大家思考什么,而是要教大家如何思考,要让你的大脑参与进来,让你去想:‘这个消息是谁创建的?为什么?为什么现在我会看到它?它让我产生了什么感觉?这又是为什么?’”

很多人认为,打击网络虚假信息最好的方法,就是对这个问题立法,并且改变现有的推荐算法。一些科技公司也在研究自己对虚假信息问题的解决方案。

但是,教大家如何识别网络虚假信息,或许才是最为有效的方法。比如最近,美国新泽西州、伊利诺伊州和得克萨斯州等地的学校都实施了新的网络素养授课标准,教学内容相当广泛,涉及互联网与社交媒体的运营方式,如何通过不同的消息来源识别虚假信息,以及对断章取义的消息和高度情绪化的标题保持警惕,等等。

美国的媒体素养课程通常被包含在历史、政府或者其他社会研究课程之中,学生一般会在高中阶段接触到这些课程。不过专家认为,任何年龄段的网民进行相关学习都是非常有益的。

例如,按照芬兰政府的反虚假信息计划,芬兰儿童从幼儿园开始就会接触到互联网的有关知识,这也是为了“从娃娃抓起”提高全民的反虚假宣传意识。

芬兰科学与文化部的部长佩特里·洪科宁近日在接受采访时表示:“在网络时代之前,媒体素养是我们最关注的问题之一。重点是培养人们的批判性思维,这是每个人越来越需要的技能。我们必须以某种方式保护人民、捍卫民主。”

洪科宁在今年年初访问华盛顿期间曾经接受美联社(The Associated Press)的专访,此访期间,他也在相关会议上讨论了芬兰打击网上虚假信息的工作。芬兰在近期的一份西方民主国家媒体素养工作报告中被排在榜首,加拿大被排在第7名,而美国排在第18名。

在芬兰,这些课程并非只是面向小学生。政府部门还会向国民发布提醒,告诉大家如何避免虚假网络信息和通过多个来源核实新闻真伪。另外,芬兰还有一些针对老年人的项目,因为与年轻网民相比,足不出户的老年网民更容易受到虚假信息的伤害。

在美国,有些尝试开设网络素养课程的学校甚至遭到了以政治为理由的反对,有人将这种课程等同于“思想控制”。肖恩·李称,由于这种担忧,很多老师甚至不敢尝试讲这样的课。

从几年前开始,华盛顿大学(University of Washington)发起了“警惕虚假信息日”(MisinfoDay)活动,他们将高中生们组织起来,以媒体素养为主题,开展为期一天的演讲、练习等主题活动。今年,华盛顿大学也举办了三场“警惕虚假信息日”主题活动,共吸引了全州的700名学生参加。

活动的发起者、华盛顿大学的教授杰文·韦斯特表示,他听说其他州甚至澳大利亚的一些教育工作者也有兴趣举办类似的活动。

韦斯特称:“也许终有一天,全美国都会有一个专门的日子来提醒人们关注媒体素养。在对抗虚假信息方面,我们有很多事情可以做,比如在监管、技术和研究上,但没有什么事情是比提高我们自身的识别能力更重要的了。”

对于疲于应对各种教学任务的老师们来说,媒体素养只是又增加了一项教学任务而已。但居住在马萨诸塞州的一位母亲艾琳·麦克尼尔认为,在未来的经济中,这项技能与计算机工程和软件编程同样重要。为此,麦克尼尔创办了一家名叫Media Literacy Now的全国性非盈利机构,倡导开展数字素养教育。

她说:“这是一个创新问题。数字化通信是信息经济的基础,而如果我们不解决好虚假信息的问题,就将对我们的经济产生巨大影响。”

在我们与媒体素养专家交流时,他们经常会拿考驾照的例子来打比方。汽车早在20世纪初就已经投产,并且很快普及开来。但直到近30年后,世界上才有了第一个针对驾驶技能的课程。

那么,究竟是哪些改变催生了驾驶课程呢?首先是政府通过了规范车辆安全和驾驶员行为的法律,其次是汽车公司增加了转向柱、安全带和安全气囊等功能。于是在20世纪30年代中期,道路交通安全的倡导者开始推动强制性的驾驶技能教育。

很多虚假信息和媒体素质的研究人士认为,在对抗虚假信息上,政府、行业和教育界应当各司其职,做到有机结合,而且任何应对网络虚假信息的有效解决方案,都必须包含教育因素。

加拿大的学校早在几十年前就开设了媒体素养课程,一开始它主要教学生如何识别电视中的虚假信息,后来随着时代发展,扩展到了数字时代。加拿大媒体素养组织MediaSmarts的教育主管马修·约翰逊表示,现在媒体素养已经被公认为是学生的一项重要素质。

他说:“在公路上,我们需要限速,也需要精心设计的公路和良好的监管来确保行车安全。但同时我们也要教人们怎样安全驾驶。而在虚假信息的问题上,不管监管机构怎样做,也不管各大平台怎样做,各种内容总会出现在网民眼前,所以他们需要有工具来批判性地对待它。”(财富中文网)

译者:朴成奎

Shawn Lee, a high school social studies teacher in Seattle, wants to see lessons on the internet akin to a kind of 21st century driver’s education, an essential for modern life.

Lee has tried to bring that kind of education into his classroom, with lessons about the need to double-check online sources, to diversify newsfeeds and to bring critical thinking to the web. He’s also created an organization for other teachers to share resources.

“This technology is so new that no one taught us how to use it,” Lee said. “People are like, ‘There’s nothing we can do,’ and they throw their hands in the air. I disagree with that. I would like to think the republic can survive an algorithm.”

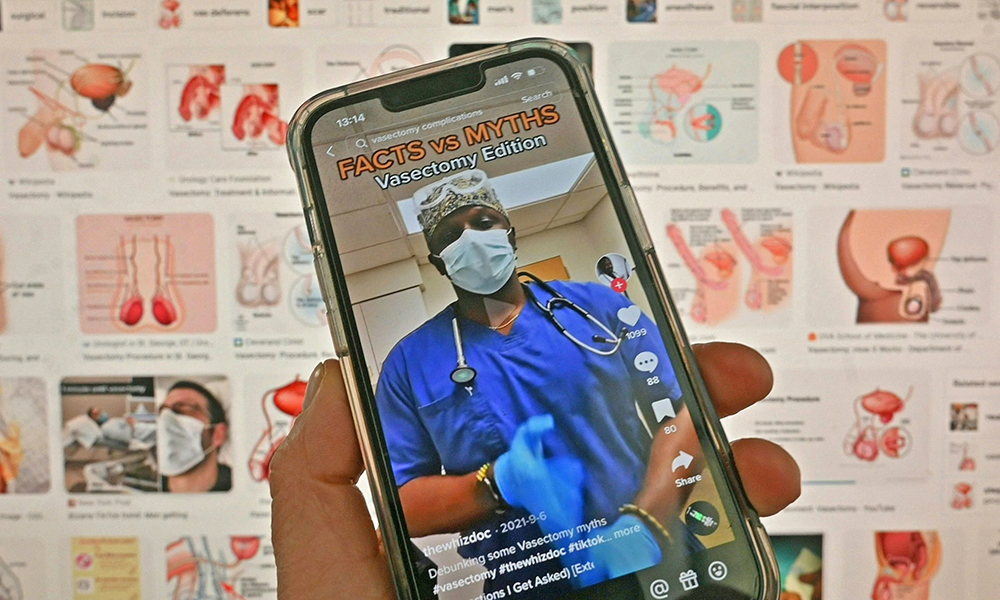

Lee’s efforts are part of a growing movement of educators and misinformation researchers working to offset an explosion of online misinformation about everything from presidential politics to pandemics. So far, the U.S. lags many other democracies in waging this battle, and the consequences of inaction are clear.

But for teachers already facing myriad demands in the classroom, incorporating internet literacy can be a challenge — especially given how politicized misinformation about vaccines, public health, voting, climate change and Russia’s war in Ukraine has become. The title of a talk for a recent gathering of Lee’s group: “How to talk about conspiracy theories without getting fired.”

“It’s not teaching what to think, but how to think,” said Julie Smith, an expert on media literacy who teaches at Webster University in Webster Groves, Missouri. “It’s engaging about engaging your brain. It’s asking, ‘Who created this? Why? Why am I seeing it now? How does it make me feel and why?’”

New laws and algorithm changes are often offered as the most promising ways of combating online misinformation, even as tech companies study their own solutions.

Teaching internet literacy, however, may be the most effective method. New Jersey, Illinois and Texas are among states that have recently implemented new standards for teaching internet literacy, a broad category that can include lessons about how the internet and social media work, along with a focus on how to spot misinformation by cross-checking multiple sources and staying wary of claims with missing context or highly emotional headlines.

Media literacy lessons are often included in history, government or other social studies classes, and typically offered at the high school level, though experts say it’s never too early — or late — to help people become better users of the internet.

Finnish children begin to learn about the internet in preschool, part of a robust anti-misinformation program that aims to make the country’s residents more resistant to false online claims.

“Media literacy was one of our priorities before the time of the internet,” Petri Honkonen, Finland’s minister of science and culture, said in a recent interview. “The point is critical thinking, and that is a skill that everybody needs more and more. We have to somehow protect people. We also must protect democracy.”

Honkonen spoke with The Associated Press earlier this year during a trip to Washington that included meetings to discuss Finland’s work to fight online misinformation. One recent report on media literacy efforts in western democracies placed Finland at the top. Canada ranked seventh, while the U.S. came in at No. 18.

In Finland the lessons don’t end with primary school. Public service announcements offer tips on avoiding false online claims and checking multiple sources. Additional programs are geared toward older adults, who can be especially vulnerable to misinformation compared to younger users more at home on the internet.

In the U.S., attempts to teach internet literacy have run into political opposition from people who equate it to thought control. Lee, the Seattle teacher, said that concern prevents some teachers from even trying.

Several years ago, the University of Washington launched MisinfoDay, which brought high schoolers and their teachers together for a one-day event featuring speakers, exercises and activities focused on media literacy. Seven hundred students from across the state attended one of three MisinfoDays this year.

Jevin West, the University of Washington professor who created the event, said he’s heard from educators in other states and as far away as Australia who are interested in creating something similar.

“Maybe eventually, someday, nationally here in the United States, we have a day devoted to the idea of media literacy,” West said. “There are all sorts of things we can do in terms of regulations, technology, in terms of research, but nothing is going to be more important than this idea of making us more resilient” to misinformation.

For teachers already struggling with other classroom demands, adding media literacy can seem like just one more obligation. But it’s a skill that is just as important as computer engineering or software coding for the future economy, according to Erin McNeill, a Massachusetts mother who started Media Literacy Now, a national nonprofit that advocates for digital literacy education.

“This is an innovation issue,” McNeill said. “Basic communication is part of our information economy, and there will be huge implications for our economy if we don’t get this right.”

The driver’s education analogy comes up a lot when talking to media literacy experts. Automobiles first went into production in the early 20th century and soon became popular. But it was nearly three decades before the first driver’s education courses were offered.

What changed? Governments passed laws regulating vehicle safety and driver behavior. Auto companies added features like collapsible steering columns, seat belts and air bags. And in the mid-1930s, safety advocates began to push for mandated driver’s education.

That combination of government, industry and educators is seen as a model by many misinformation and media literacy researchers. Any effective solution to the challenges posed by online misinformation, they say, must by necessity include an educational component.

Media literacy in Canadian schools began decades ago and initially focused on television before being expanded throughout the digital era. Now it’s accepted as an essential part of preparing students, according to Matthew Johnson, director of education at MediaSmarts, an organization that leads media literacy programs in Canada.

“We need speed limits, we need well-designed roads and good regulations to ensure cars are safe. But we also teach people how to drive safely,” he said. “Whatever regulators do, whatever online platforms do, content always winds up in front of an audience, and they need to have the tools to engage critically with it.”