因为这个原因,千禧一代不愿生孩子

乔伊和她的丈夫刚刚迎来了一个侄女。这个孩子是乔伊时年33岁的嫂子生的,侄女的出生让这对夫妇意识到他们多么希望能够有自己的孩子。他们在大学里相识,后来一直住在密歇根州东部,希望有两到三个孩子。“她太可爱了!”乔伊夸张地称赞着自己的侄女。她满脑子都在想:“现在我真的想要一个孩子了。”但横亘在现实情况和理想家庭之间的主要障碍是6万美元的学生贷款,每月最低还款额为800美元。她们无法想象自己如何负担得起生育费用,更别提数年的儿童保育费用了。“这在经济上是行不通的。”她说。

乔伊今年26岁,出于隐私考虑,她要求只保留名字。为确保自己一大学毕业就可以找到工作,而且没有太多债务,她对自己的教育规划非常细致。她的父母为她存了2.4万美元。她和父亲制作了电子表格来规划成本。但是,“未考虑到的隐藏费用”和成为注册会计师所需要的额外30个学分,把她的全盘计划都打翻了。他们在毕业时欠下了7.4万美元的债务,其中略多于一半是她欠的。

毕业后,她和丈夫都在各自的领域中找到了稳定的工作(她的丈夫是一名护士)。他们的年收入加起来超过10万美元。在这几年里,他们都得到了加薪,但这些额外的收入都用于偿还1.5万美元的债务。他们每月将大部分能够自由支配的开支——扣除账单和贷款后约500美元——也用于偿还欠款。

根据美国总统乔·拜登提出的一次性计划,乔伊和她丈夫是4,300万有资格获得1万美元或2万美元联邦学生贷款减免的借款人之一。拜登政府的免除学生贷款计划成本高达4,000亿美元。这对夫妇和他们的同龄人是否可以得到任何减免仍然不得而知。六个由共和党领导的州试图推翻拜登政府的计划,声称这将损害未来的税收收入,还有两名个人借款人声称他们被不公正地剥夺了就该计划发表意见的机会。美国最高法院(Supreme Court)于2月28日听取这两起案件的口头辩论,预计将在6月底做出裁决。

即使大法官支持该计划,许多负债累累的千禧一代的债务负担也只会减少一小部分。但对其他人来说,这种减免对他们是否能够考虑成家有着重大影响。无论如何,如此多的年轻人被迫在财务和家庭之间做出选择,这一严峻形势突显出美国的学生贷款负担变得如此沉重,压得借款人喘不过气来。

俄亥俄州立大学(Ohio State University)的研究学生贷款对人口的影响的研究员迈克尔·诺表示,这是历史上第一次学生债务涉及范围如此之广,负担如此之重。“这几乎就像是社会实验,看看这会对生活的其他部分产生什么影响?”

拜登政府的免除学生贷款计划将“改变”乔伊和她丈夫的生活,他们每月的最低还款额将从800美元缩减到250美元。“如果这样的话,我们就可以开始为组建家庭和买房子存钱了。”她说。如果拜登政府的免除学生贷款计划泡汤,他们的工资加起来就根本“不够抚养一个孩子”。

在时年近四十岁的大学毕业生中,约有三分之二的人申请过教育贷款,美国千禧一代平均负债超过4万美元。由于长期存在的种族贫富差距,来自非裔和拉美裔家庭的学生上大学更有可能要靠贷款。债务负担侵蚀了借款人在餐饮、旅游和消费品等项目上的可自由支配支出。贷款清偿义务也迫使借款人推迟购买大件商品,例如他们的第一套房子。但学生贷款也在改变人们的亲密关系,阻碍他们约会、结婚或者为人父母。

千禧一代要孩子的时间推迟了,这一事实通常被认为是一种主动选择。但是,许多背负着巨额学生贷款的年轻人认为,只要他们还在为贷款忧虑不已,就不会选择要孩子。他们还得从儿童保育费用中抽钱来偿还债务,这样的情况甚至让那些收入高于平均水平的人感到不安,无法为未来做计划。2015年的一项研究估计,在控制了教育、阶级背景和人口统计学指标等变量后,背负6万美元学生债务的女性生孩子的可能性比无债务的同龄人低42%。美国大学女性协会(American Association of University Women)的数据显示,女性背负约三分之二的学生贷款债务。

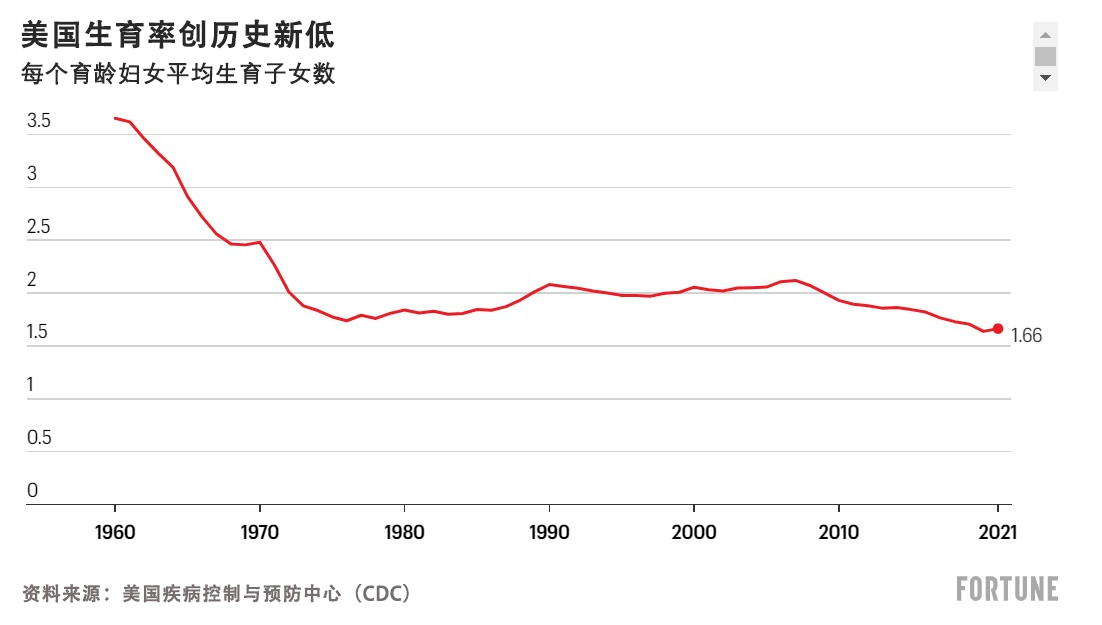

借款人对组建家庭的犹豫不决导致了美国出生率下降,美国的生育率已经跌至半个世纪以来的最低水平。出生率的下降会导致人口老龄化,劳动力和税收基数减少,以及无资金准备的养老金负债的风险。从这个意义上说,学生债务负担不仅是让一些满怀希望想要为人父母的人的梦想破灭,而且是可能会影响几代人的宏观经济冲击。

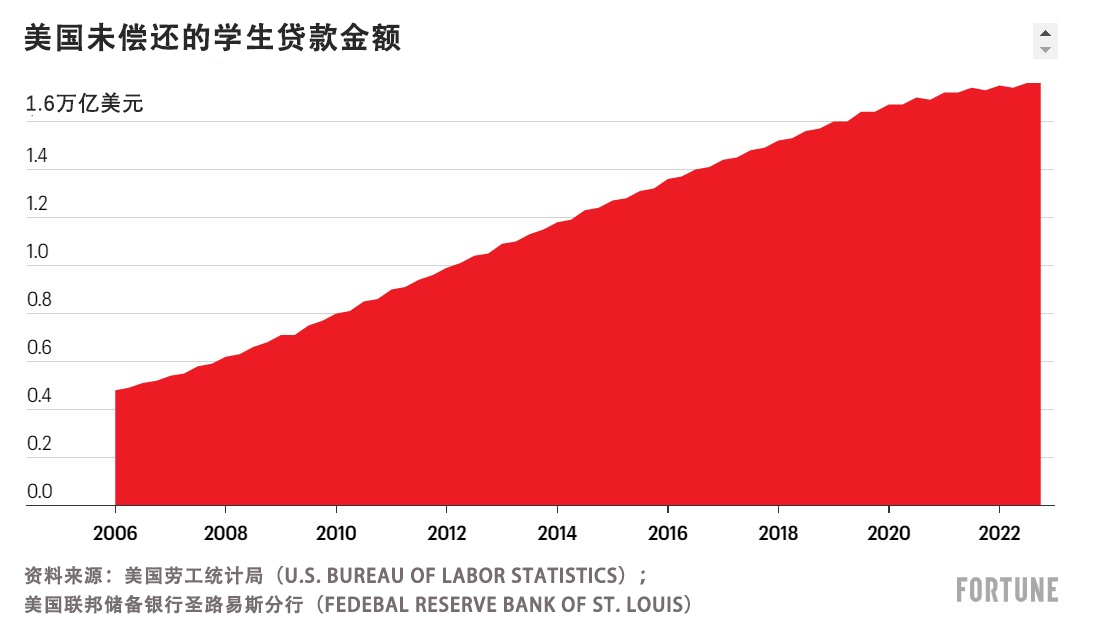

美国学生贷款飙升;出生率下降

时年40岁的社会学家阿里尔·库珀伯格在看到沉重的贷款负担如何迫使她的朋友在个人生活中做出艰难的选择后,开始研究学生债务如何影响年轻人向成年人过渡。为了节省房租和偿还贷款,一位朋友在大学毕业后就搬到了母亲的地下室,这让他在整个二三十岁时期都很难进行约会。另一个朋友背负着超过10万美元的学生贷款债务,虽然她想要一个孩子,但她认为自己负担不起。

通过分析国家贷款数据,库珀伯格和他的同事、社会学家琼·玛雅·马泽利斯发现,这些不仅仅是轶事。他们发现,在20世纪80年代初出生的拥有大学学位的女性中,60%申请过助学贷款的女性在40岁前有了孩子,而没有申请过助学贷款的女性的这一比例为67.5%。库珀伯格称,“在生育率方面”,这7.5个百分点的差距是“巨大的”,相当于约71.5万名处于最佳生育年龄的女性。“你需要关注的是,这一代人是否有后代?”答案显然是没有。在美国,2020年的总和生育率达到了每个育龄妇女平均生育1.64个孩子,为20世纪70年代以来的最低水平;同年,美国累计学生贷款债务达到近1.7万亿美元。库珀伯格和马泽利斯对东北部和东南部两所中型公立大学的近3,000名本科生进行了调查,结果显示,47%的人认为,如果他们有未偿还的贷款债务,就不应该要孩子。

美国千禧一代并不是唯一一个对生育犹豫不决的群体。世界上大约有一半的人口生活在总和生育率(一位女性一生中预期可生育的孩子数量)低于2.1的国家,而这是保持人口稳定的生育率水平。但美国在大学毕业生负债问题上是独一无二的,这要归咎于数十年来公立高等教育拨款削减,以及不断上涨的学费,这使得美国家庭每年要承担五位数的学费账单。

在富裕国家中,美国也因为缺乏全国性的带薪家事假,而且国家层面给家庭提供的援助很少而独树一帜。这就让个人不得不凑钱在分娩后休假,或者开始支付托儿费用。

库珀伯格和马泽利斯从权衡的角度考虑了这种情况。库珀伯格表示:“这越来越成为一种经济形势,你能够拥有一样东西,但无法拥有所有。家庭、经济保障、大学学位,或者没有太多债务——你只可以得到其中的一两个。”

时年34岁的埃利奥特·金德勒目前考虑的是经济保障。2011年,他从埃默里大学(Emory University)毕业,获得了宗教学学位,并欠下了4万美元学贷。在经济仍然在从金融危机中复苏的情况下,他能够找到的最好的工作岗位是由美国银行(Bank of America)提供的,这家银行收购了抵押贷款机构Countrywide Financial。他住在家里,用3.7万美元的工资偿还债务,处理止赎——“那是我生命中相当悲惨的三年。”他回忆道。金德勒认为研究生学位是“让自己可以找到工作”的唯一途径。MBA学位可能会让他背负更多的债务,但从长远来看,这将使他获得更丰厚的薪水。他的赌注得到了回报:匹兹堡大学(University of Pittsburgh)的MBA学位让他又背上了6万美元的债务,但也让他在德勤公司(Deloitte)找到了一份年薪10.5万美元的工作。后来,他在北弗吉尼亚州的一家网络安全公司处理公司财务方面的工作,该公司被谷歌(Google)收购。现在他是谷歌的员工,包括股权和奖金在内,他的年薪超过20万美元。

在这一过程中,他遇到了他的妻子,她是一所公立学校的教师,他在结婚后得知她有大约8.5万美元的贷款。由于精打细算,他们的学贷从最初的18.5万美元降至7.8万美元。金德勒为自己的年薪从3.7万美元涨到十年后超过20万美元而感到自豪。“但与此同时,这些学生贷款并没有消失。”他说。他们的剩余债务需要每月偿还近2,000美元,这比他估计的北弗吉尼亚州每月1,600美元的儿童保育费用还要高。

这对夫妇在2020年和2021年的收入让他们有资格参加拜登政府的学生贷款减免计划,而他的妻子作为一名政府雇员,有资格参加一项针对公共或非营利部门工作人员的单独贷款减免计划。金德勒指出,这些项目最终将减轻他们大约4.5万美元的联邦债务,“但这取决于政治力量”。他估计,他们能够在三年到四年内还清剩余的贷款。到那时,他们都已经37岁或者38岁了,将要面临“要一个孩子还是不要孩子?”的抉择。希望听起来积极一点,我提到了谷歌提供的优厚的生育福利。金德勒表示他知道这些福利,但他觉得这些福利似乎是为了鼓励人们多工作,推迟生育,直到他们需要医疗帮助。(自2010年代中期大型科技公司开始为员工提供冷冻卵子服务以来,观察人士和科技工作者自己也提出了类似的批评。)“我不想说这是一件坏事。我认为他们提供福利的做法很好。只是——你知道的,天下没有免费的午餐。”

金德勒的弟弟是一名医生,比他小两岁,收入和他一样多。但由于弟弟在一家严格意义上是非营利性的医院系统工作,他很快就有资格获得贷款减免。今年1月,弟弟宣布他的妻子已经怀有身孕。

借更多钱来赚更多钱

乔伊很幸运,仅凭本科学位就找到了一份好工作。但是,像金德勒一样,许多年轻人为了获得更高的学位而背负额外的债务,以便在竞争激烈的领域走得更远。丹尼·纳瓦罗在非营利部门“多次换工作又多次失业”后,意识到自己唯一的出路是获得公共管理硕士学位。在华盛顿地区学费较低的乔治梅森大学(George Mason University)攻读硕士学位仍然需要7万美元的贷款。时年34岁的纳瓦罗说:“要想获得更高的薪水,就需要攻读硕士学位,但这感觉就像陷入了一场激烈的竞争中:为了偿还这些贷款,就要多赚2万美元。”他仍然在非营利部门工作。“我们现在不得不把每月收入的近四分之一用来还债。”

他的妻子劳里·纳瓦罗在美国政府的公共事务部门工作。她的父母是华盛顿州农村地区的农业工人,家中有五个孩子,她是老大。她一直以为自己会有四个孩子。但今天,37岁的她不再确定这一想法是否现实可行,自从她在2020年被诊断出患有不明原因的不孕症后,她就更不确定了。巨额学生债务——她的7万美元和丹尼的2.5万美元——成了拦路虎。

如果没有债务,“我们就可以把钱花在收养或者体外受精上。”他说。

加州大学洛杉矶分校(University of California, Los Angeles)的社会学副教授娜塔莎·夸德林研究过学生贷款债务,她指出,有学贷的女性可能上过大学,而受过大学教育的女性往往倾向于晚育。“如果受过大学教育的女性因为债务而进一步推迟生育,她们可能就会面临进一步的生育挑战和其他与怀孕相关的并发症。简而言之,债务减免可能相当于为一些女性消除了生育方面的重大障碍。”夸德林补充道。

公司提供学生贷款减免

如果学生债务导致年轻人推迟或放弃生育,那么有什么解决方案能够解决他们的担忧?拜登政府的免除学生贷款计划肯定可以给很多人提供帮助,让他们更轻松地推进家庭计划——根据美国联邦储备银行圣路易斯分行(Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)的数据,大约三分之二的千禧一代的学生债务在2万美元或以下。

夸德林指出:“在美国生孩子是非常昂贵的,通过免除债务而省下来的可支配收入能够重新用于对下一代的投资。”

但对于有巨额债务的借款人而言,这可能微不足道。左倾智库罗斯福研究所(Roosevelt Institute)的研究和政策常务董事苏珊·卡恩说,此外,旨在为家庭提供帮助的政策充满政治和法律上的不确定性,使得人们很难把握自己的未来财务状况。“对那些试图组建家庭的人而言”,学生贷款减免和扩大儿童税收抵免是“非常受欢迎的,也是人们迫切需要的,”但她补充说:“真正需要的是政策到位。让我感到非常悲哀的是,一系列政策往往卡在最高法院和国会之间,无法到位。”

在过去20年里,各州都颁布了家庭援助计划。在联邦层面,由马萨诸塞州民主党参议员伊丽莎白·沃伦、新泽西州民主党众议员米基·谢里尔和加利福尼亚州民主党众议员萨拉·雅各布斯共同发起的《社区儿童保育法案》(Child Care for Every Community Act)将高收入家庭的儿童保育费用限制在总收入的7%以内,而一半的美国家庭每天将支付10美元或者更少的托儿费。

企业意识到员工对拥有家庭的渴望。管理咨询公司美世(Mercer)2022年对雇主健康计划的调查显示,科技公司从2014年开始提供冷冻卵子福利,如今54%的大公司将体外受精纳入报销范围。但是,将儿童保育费用纳入报销范围却并不常见。密西西比州的婴儿看护费用为每年5,436美元,华盛顿特区为每年24,243美元。户外服装公司Patagonia是罕见的例外,该公司自1983年起就在总部提供现场托儿服务。

其他公司已经开始认真对待员工的学生贷款。谷歌宣布在2020年提供每年2,500美元的贷款偿还福利;普华永道(PwC)提供总额高达1万美元的还款援助。这样的福利有助于公司吸引人才。美世在2022年对4,000多名员工进行的一项调查发现,第二大最受员工欢迎的固定缴款计划福利是雇主按照一定比例帮助员工偿还学生贷款债务,这也是员工希望公司提供的福利,仅次于雇主提高员工养老金计划缴款数额。对45岁以下的员工来说,这是首选。

“热爱你所做的”——还是减少贷款?

雷切尔·布洛姆奎斯特很想为一家帮助员工偿还学生贷款或提供儿童保育费用的公司工作。“这将对我决定去哪里工作产生巨大影响。”她说。时年34的她在一家教育技术公司担任用户体验设计师,背负着17.74万美元的学生债务:攻读克赖顿大学(Creighton University)人类学本科学位的学贷约为2万美元,攻读乔治敦大学(Georgetown University)的东亚研究硕士学位的学贷超过14.8万美元,外加约1万美元的利息。

我问她是否了解她为攻读硕士学位而申请的贷款的金额。当时,她希望进入国际发展领域的非营利组织工作,并在10年后有资格获得公共服务贷款减免。她说:“我只是——看到这些数字就愣住了,因为我还是无法理解这些数字到底意味着什么。”她还习惯了这样看待这些贷款:每月工资的一定比例用于偿还学贷,而不是考虑全部贷款到底有多少。“在我看来,我可以说:‘哦,好吧,我只需将未来25年收入的10%用于偿还学贷。我能够做到这一点。’”

直到她在2020年结婚,她按月还贷的方式才变得难以维持。根据她和丈夫的综合收入,她每月的最低还款额很快将从300美元跳到900美元。她和丈夫希望至少有一个孩子,也许是两个,现在她终于觉得自己做好心理准备了。但是,她说:“由于学生贷款,我仍然觉得在经济上没有做好准备……我个人的经济状况非常不稳定,更别提有一个孩子了。当然,我认为自己养不起两个孩子。”

通过拜登政府的计划免除2万美元将使她的欠款降至15万美元——“这个数字看起来干净利落。”她说——她目前正在试图从更全面的角度考虑这个问题,并尝试从整体的角度应对这个问题。“实际上,我一直在想,我怎么才可以还清这笔贷款?我怎样才能够摆脱这笔债务呢?”她说。“但目前没有任何方法可以让我真正还清这笔钱。”如果他们真的有孩子,她想知道她将如何告诉孩子们关于学生贷款的事情。她说:“我希望我的孩子能够像我小时候那样长大——做自己喜欢的事情。但我的学生贷款告诉我不能做我喜欢的事情。”(财富中文网)

该文章是在经济困难报告项目(Economic Hardship Reporting Project)的支持下完成的。

译者:中慧言-王芳

乔伊和她的丈夫刚刚迎来了一个侄女。这个孩子是乔伊时年33岁的嫂子生的,侄女的出生让这对夫妇意识到他们多么希望能够有自己的孩子。他们在大学里相识,后来一直住在密歇根州东部,希望有两到三个孩子。“她太可爱了!”乔伊夸张地称赞着自己的侄女。她满脑子都在想:“现在我真的想要一个孩子了。”但横亘在现实情况和理想家庭之间的主要障碍是6万美元的学生贷款,每月最低还款额为800美元。她们无法想象自己如何负担得起生育费用,更别提数年的儿童保育费用了。“这在经济上是行不通的。”她说。

乔伊今年26岁,出于隐私考虑,她要求只保留名字。为确保自己一大学毕业就可以找到工作,而且没有太多债务,她对自己的教育规划非常细致。她的父母为她存了2.4万美元。她和父亲制作了电子表格来规划成本。但是,“未考虑到的隐藏费用”和成为注册会计师所需要的额外30个学分,把她的全盘计划都打翻了。他们在毕业时欠下了7.4万美元的债务,其中略多于一半是她欠的。

毕业后,她和丈夫都在各自的领域中找到了稳定的工作(她的丈夫是一名护士)。他们的年收入加起来超过10万美元。在这几年里,他们都得到了加薪,但这些额外的收入都用于偿还1.5万美元的债务。他们每月将大部分能够自由支配的开支——扣除账单和贷款后约500美元——也用于偿还欠款。

根据美国总统乔·拜登提出的一次性计划,乔伊和她丈夫是4,300万有资格获得1万美元或2万美元联邦学生贷款减免的借款人之一。拜登政府的免除学生贷款计划成本高达4,000亿美元。这对夫妇和他们的同龄人是否可以得到任何减免仍然不得而知。六个由共和党领导的州试图推翻拜登政府的计划,声称这将损害未来的税收收入,还有两名个人借款人声称他们被不公正地剥夺了就该计划发表意见的机会。美国最高法院(Supreme Court)于2月28日听取这两起案件的口头辩论,预计将在6月底做出裁决。

即使大法官支持该计划,许多负债累累的千禧一代的债务负担也只会减少一小部分。但对其他人来说,这种减免对他们是否能够考虑成家有着重大影响。无论如何,如此多的年轻人被迫在财务和家庭之间做出选择,这一严峻形势突显出美国的学生贷款负担变得如此沉重,压得借款人喘不过气来。

俄亥俄州立大学(Ohio State University)的研究学生贷款对人口的影响的研究员迈克尔·诺表示,这是历史上第一次学生债务涉及范围如此之广,负担如此之重。“这几乎就像是社会实验,看看这会对生活的其他部分产生什么影响?”

拜登政府的免除学生贷款计划将“改变”乔伊和她丈夫的生活,他们每月的最低还款额将从800美元缩减到250美元。“如果这样的话,我们就可以开始为组建家庭和买房子存钱了。”她说。如果拜登政府的免除学生贷款计划泡汤,他们的工资加起来就根本“不够抚养一个孩子”。

在时年近四十岁的大学毕业生中,约有三分之二的人申请过教育贷款,美国千禧一代平均负债超过4万美元。由于长期存在的种族贫富差距,来自非裔和拉美裔家庭的学生上大学更有可能要靠贷款。债务负担侵蚀了借款人在餐饮、旅游和消费品等项目上的可自由支配支出。贷款清偿义务也迫使借款人推迟购买大件商品,例如他们的第一套房子。但学生贷款也在改变人们的亲密关系,阻碍他们约会、结婚或者为人父母。

千禧一代要孩子的时间推迟了,这一事实通常被认为是一种主动选择。但是,许多背负着巨额学生贷款的年轻人认为,只要他们还在为贷款忧虑不已,就不会选择要孩子。他们还得从儿童保育费用中抽钱来偿还债务,这样的情况甚至让那些收入高于平均水平的人感到不安,无法为未来做计划。2015年的一项研究估计,在控制了教育、阶级背景和人口统计学指标等变量后,背负6万美元学生债务的女性生孩子的可能性比无债务的同龄人低42%。美国大学女性协会(American Association of University Women)的数据显示,女性背负约三分之二的学生贷款债务。

借款人对组建家庭的犹豫不决导致了美国出生率下降,美国的生育率已经跌至半个世纪以来的最低水平。出生率的下降会导致人口老龄化,劳动力和税收基数减少,以及无资金准备的养老金负债的风险。从这个意义上说,学生债务负担不仅是让一些满怀希望想要为人父母的人的梦想破灭,而且是可能会影响几代人的宏观经济冲击。

美国学生贷款飙升;出生率下降

时年40岁的社会学家阿里尔·库珀伯格在看到沉重的贷款负担如何迫使她的朋友在个人生活中做出艰难的选择后,开始研究学生债务如何影响年轻人向成年人过渡。为了节省房租和偿还贷款,一位朋友在大学毕业后就搬到了母亲的地下室,这让他在整个二三十岁时期都很难进行约会。另一个朋友背负着超过10万美元的学生贷款债务,虽然她想要一个孩子,但她认为自己负担不起。

通过分析国家贷款数据,库珀伯格和他的同事、社会学家琼·玛雅·马泽利斯发现,这些不仅仅是轶事。他们发现,在20世纪80年代初出生的拥有大学学位的女性中,60%申请过助学贷款的女性在40岁前有了孩子,而没有申请过助学贷款的女性的这一比例为67.5%。库珀伯格称,“在生育率方面”,这7.5个百分点的差距是“巨大的”,相当于约71.5万名处于最佳生育年龄的女性。“你需要关注的是,这一代人是否有后代?”答案显然是没有。在美国,2020年的总和生育率达到了每个育龄妇女平均生育1.64个孩子,为20世纪70年代以来的最低水平;同年,美国累计学生贷款债务达到近1.7万亿美元。库珀伯格和马泽利斯对东北部和东南部两所中型公立大学的近3,000名本科生进行了调查,结果显示,47%的人认为,如果他们有未偿还的贷款债务,就不应该要孩子。

美国千禧一代并不是唯一一个对生育犹豫不决的群体。世界上大约有一半的人口生活在总和生育率(一位女性一生中预期可生育的孩子数量)低于2.1的国家,而这是保持人口稳定的生育率水平。但美国在大学毕业生负债问题上是独一无二的,这要归咎于数十年来公立高等教育拨款削减,以及不断上涨的学费,这使得美国家庭每年要承担五位数的学费账单。

在富裕国家中,美国也因为缺乏全国性的带薪家事假,而且国家层面给家庭提供的援助很少而独树一帜。这就让个人不得不凑钱在分娩后休假,或者开始支付托儿费用。

库珀伯格和马泽利斯从权衡的角度考虑了这种情况。库珀伯格表示:“这越来越成为一种经济形势,你能够拥有一样东西,但无法拥有所有。家庭、经济保障、大学学位,或者没有太多债务——你只可以得到其中的一两个。”

时年34岁的埃利奥特·金德勒目前考虑的是经济保障。2011年,他从埃默里大学(Emory University)毕业,获得了宗教学学位,并欠下了4万美元学贷。在经济仍然在从金融危机中复苏的情况下,他能够找到的最好的工作岗位是由美国银行(Bank of America)提供的,这家银行收购了抵押贷款机构Countrywide Financial。他住在家里,用3.7万美元的工资偿还债务,处理止赎——“那是我生命中相当悲惨的三年。”他回忆道。金德勒认为研究生学位是“让自己可以找到工作”的唯一途径。MBA学位可能会让他背负更多的债务,但从长远来看,这将使他获得更丰厚的薪水。他的赌注得到了回报:匹兹堡大学(University of Pittsburgh)的MBA学位让他又背上了6万美元的债务,但也让他在德勤公司(Deloitte)找到了一份年薪10.5万美元的工作。后来,他在北弗吉尼亚州的一家网络安全公司处理公司财务方面的工作,该公司被谷歌(Google)收购。现在他是谷歌的员工,包括股权和奖金在内,他的年薪超过20万美元。

在这一过程中,他遇到了他的妻子,她是一所公立学校的教师,他在结婚后得知她有大约8.5万美元的贷款。由于精打细算,他们的学贷从最初的18.5万美元降至7.8万美元。金德勒为自己的年薪从3.7万美元涨到十年后超过20万美元而感到自豪。“但与此同时,这些学生贷款并没有消失。”他说。他们的剩余债务需要每月偿还近2,000美元,这比他估计的北弗吉尼亚州每月1,600美元的儿童保育费用还要高。

这对夫妇在2020年和2021年的收入让他们有资格参加拜登政府的学生贷款减免计划,而他的妻子作为一名政府雇员,有资格参加一项针对公共或非营利部门工作人员的单独贷款减免计划。金德勒指出,这些项目最终将减轻他们大约4.5万美元的联邦债务,“但这取决于政治力量”。他估计,他们能够在三年到四年内还清剩余的贷款。到那时,他们都已经37岁或者38岁了,将要面临“要一个孩子还是不要孩子?”的抉择。希望听起来积极一点,我提到了谷歌提供的优厚的生育福利。金德勒表示他知道这些福利,但他觉得这些福利似乎是为了鼓励人们多工作,推迟生育,直到他们需要医疗帮助。(自2010年代中期大型科技公司开始为员工提供冷冻卵子服务以来,观察人士和科技工作者自己也提出了类似的批评。)“我不想说这是一件坏事。我认为他们提供福利的做法很好。只是——你知道的,天下没有免费的午餐。”

金德勒的弟弟是一名医生,比他小两岁,收入和他一样多。但由于弟弟在一家严格意义上是非营利性的医院系统工作,他很快就有资格获得贷款减免。今年1月,弟弟宣布他的妻子已经怀有身孕。

借更多钱来赚更多钱

乔伊很幸运,仅凭本科学位就找到了一份好工作。但是,像金德勒一样,许多年轻人为了获得更高的学位而背负额外的债务,以便在竞争激烈的领域走得更远。丹尼·纳瓦罗在非营利部门“多次换工作又多次失业”后,意识到自己唯一的出路是获得公共管理硕士学位。在华盛顿地区学费较低的乔治梅森大学(George Mason University)攻读硕士学位仍然需要7万美元的贷款。时年34岁的纳瓦罗说:“要想获得更高的薪水,就需要攻读硕士学位,但这感觉就像陷入了一场激烈的竞争中:为了偿还这些贷款,就要多赚2万美元。”他仍然在非营利部门工作。“我们现在不得不把每月收入的近四分之一用来还债。”

他的妻子劳里·纳瓦罗在美国政府的公共事务部门工作。她的父母是华盛顿州农村地区的农业工人,家中有五个孩子,她是老大。她一直以为自己会有四个孩子。但今天,37岁的她不再确定这一想法是否现实可行,自从她在2020年被诊断出患有不明原因的不孕症后,她就更不确定了。巨额学生债务——她的7万美元和丹尼的2.5万美元——成了拦路虎。

如果没有债务,“我们就可以把钱花在收养或者体外受精上。”他说。

加州大学洛杉矶分校(University of California, Los Angeles)的社会学副教授娜塔莎·夸德林研究过学生贷款债务,她指出,有学贷的女性可能上过大学,而受过大学教育的女性往往倾向于晚育。“如果受过大学教育的女性因为债务而进一步推迟生育,她们可能就会面临进一步的生育挑战和其他与怀孕相关的并发症。简而言之,债务减免可能相当于为一些女性消除了生育方面的重大障碍。”夸德林补充道。

公司提供学生贷款减免

如果学生债务导致年轻人推迟或放弃生育,那么有什么解决方案能够解决他们的担忧?拜登政府的免除学生贷款计划肯定可以给很多人提供帮助,让他们更轻松地推进家庭计划——根据美国联邦储备银行圣路易斯分行(Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)的数据,大约三分之二的千禧一代的学生债务在2万美元或以下。

夸德林指出:“在美国生孩子是非常昂贵的,通过免除债务而省下来的可支配收入能够重新用于对下一代的投资。”

但对于有巨额债务的借款人而言,这可能微不足道。左倾智库罗斯福研究所(Roosevelt Institute)的研究和政策常务董事苏珊·卡恩说,此外,旨在为家庭提供帮助的政策充满政治和法律上的不确定性,使得人们很难把握自己的未来财务状况。“对那些试图组建家庭的人而言”,学生贷款减免和扩大儿童税收抵免是“非常受欢迎的,也是人们迫切需要的,”但她补充说:“真正需要的是政策到位。让我感到非常悲哀的是,一系列政策往往卡在最高法院和国会之间,无法到位。”

在过去20年里,各州都颁布了家庭援助计划。在联邦层面,由马萨诸塞州民主党参议员伊丽莎白·沃伦、新泽西州民主党众议员米基·谢里尔和加利福尼亚州民主党众议员萨拉·雅各布斯共同发起的《社区儿童保育法案》(Child Care for Every Community Act)将高收入家庭的儿童保育费用限制在总收入的7%以内,而一半的美国家庭每天将支付10美元或者更少的托儿费。

企业意识到员工对拥有家庭的渴望。管理咨询公司美世(Mercer)2022年对雇主健康计划的调查显示,科技公司从2014年开始提供冷冻卵子福利,如今54%的大公司将体外受精纳入报销范围。但是,将儿童保育费用纳入报销范围却并不常见。密西西比州的婴儿看护费用为每年5,436美元,华盛顿特区为每年24,243美元。户外服装公司Patagonia是罕见的例外,该公司自1983年起就在总部提供现场托儿服务。

其他公司已经开始认真对待员工的学生贷款。谷歌宣布在2020年提供每年2,500美元的贷款偿还福利;普华永道(PwC)提供总额高达1万美元的还款援助。这样的福利有助于公司吸引人才。美世在2022年对4,000多名员工进行的一项调查发现,第二大最受员工欢迎的固定缴款计划福利是雇主按照一定比例帮助员工偿还学生贷款债务,这也是员工希望公司提供的福利,仅次于雇主提高员工养老金计划缴款数额。对45岁以下的员工来说,这是首选。

“热爱你所做的”——还是减少贷款?

雷切尔·布洛姆奎斯特很想为一家帮助员工偿还学生贷款或提供儿童保育费用的公司工作。“这将对我决定去哪里工作产生巨大影响。”她说。时年34的她在一家教育技术公司担任用户体验设计师,背负着17.74万美元的学生债务:攻读克赖顿大学(Creighton University)人类学本科学位的学贷约为2万美元,攻读乔治敦大学(Georgetown University)的东亚研究硕士学位的学贷超过14.8万美元,外加约1万美元的利息。

我问她是否了解她为攻读硕士学位而申请的贷款的金额。当时,她希望进入国际发展领域的非营利组织工作,并在10年后有资格获得公共服务贷款减免。她说:“我只是——看到这些数字就愣住了,因为我还是无法理解这些数字到底意味着什么。”她还习惯了这样看待这些贷款:每月工资的一定比例用于偿还学贷,而不是考虑全部贷款到底有多少。“在我看来,我可以说:‘哦,好吧,我只需将未来25年收入的10%用于偿还学贷。我能够做到这一点。’”

直到她在2020年结婚,她按月还贷的方式才变得难以维持。根据她和丈夫的综合收入,她每月的最低还款额很快将从300美元跳到900美元。她和丈夫希望至少有一个孩子,也许是两个,现在她终于觉得自己做好心理准备了。但是,她说:“由于学生贷款,我仍然觉得在经济上没有做好准备……我个人的经济状况非常不稳定,更别提有一个孩子了。当然,我认为自己养不起两个孩子。”

通过拜登政府的计划免除2万美元将使她的欠款降至15万美元——“这个数字看起来干净利落。”她说——她目前正在试图从更全面的角度考虑这个问题,并尝试从整体的角度应对这个问题。“实际上,我一直在想,我怎么才可以还清这笔贷款?我怎样才能够摆脱这笔债务呢?”她说。“但目前没有任何方法可以让我真正还清这笔钱。”如果他们真的有孩子,她想知道她将如何告诉孩子们关于学生贷款的事情。她说:“我希望我的孩子能够像我小时候那样长大——做自己喜欢的事情。但我的学生贷款告诉我不能做我喜欢的事情。”(财富中文网)

该文章是在经济困难报告项目(Economic Hardship Reporting Project)的支持下完成的。

译者:中慧言-王芳

Joy and her husband just welcomed a niece. The arrival of the child, born to Joy’s 33-year-old sister-in-law, reminded the couple how much they want kids of their own. The couple, who met in college and live in eastern Michigan, always hoped for two or three kids, and their new niece—“She is just so cute!” Joy gushed—has put it front of mind: “Now I really want one.” But one major barrier standing between them and the family they’d imagined is $60,000 in combined student loan debt. With minimum monthly loan payments of $800, they can’t fathom how they’d afford the cost of childbirth, let alone years of childcare. “It’s just not financially feasible,” she said.

Joy, who’s 26 and asked to go by only her first name for privacy reasons, was meticulous about planning her education to ensure she got a job right out of college without too much debt. Her parents had saved up a $24,000 nest egg. She and her father had built spreadsheets to map out the costs. But “stupid hidden fees” and the additional 30 credits she needed to become a certified public accountant threw a wrench in her plans. The couple had $74,000 in debt when they graduated, and slightly more than half was hers.

After graduation, she and her husband both landed steady work in their fields (her husband is a nurse). Together, they earned over $100,000 annually. They’ve both received raises in the intervening years, but that extra income went toward paying down $15,000 in debt. They routed most of their discretionary spending money every month—about $500 after bills and loan payments—toward paying down their balance too.

Joy and her husband are among the 43 million borrowers eligible for $10,000 or $20,000 in federal student loan forgiveness under a one-time plan proposed by President Joe Biden that will cost about $400 billion over 30 years. Whether the couple and their peers get any relief is up in the air. Six Republican-led states have sought to strike down Biden’s plan, claiming it will harm future tax revenue, as have two individual borrowers, who claim they were improperly denied the opportunity to comment on the plan. The Supreme Court hear oral arguments in both cases on Feb. 28, with a decision expected at the end of June.

Even if the justices uphold the plan, many of the most indebted millennials will see their debt load decrease by only a small fraction. But for others, that forgiveness could make the difference between being able to consider starting a family and not. Regardless, the fact that so many young adults see the choice between finances and family in such stark terms underscores just how large and debilitating the nation’s student loan burden has become.

This is the first time in history that student debt has been so widespread and so significant, said Michael Nau, a researcher at Ohio State University who has studied the demographic effects of student loans. “It’s almost like a social experiment to see, well, how will that have ramifications for other parts of life?”

Relief under the Biden plan would be “life-changing” for Joy and her husband, shrinking their minimum monthly payment from $800 to $250. “If that happens, we can start to save for a family and home,” she said. If not, their combined salaries are simply “not enough to raise a kid.”

About two-thirds of college-degree holders in their late thirties have borrowed money for their educations, with the average U.S. millennial holding over $40,000 in debt. Students from Black and Latino families are even more likely to borrow for college, owing to longstanding racial wealth gaps. Debt burdens eat into borrowers’ discretionary spending on items like meals, travel, and consumer goods. Repayment obligations force borrowers to put off larger purchases, too, like their first home. But student loans are also altering people’s lives in more intimate ways, by hindering their ability to date, marry, or become parents.

Millennials are waiting longer to have kids, a fact that is often framed as a choice. But many young people saddled with significant student loans don’t feel that children are an option for them, as long as debt hangs around their necks, siphoning money away from expenses like childcare and leaving even those with above-average incomes feeling precarious and unable to plan for the future. One 2015 study estimates that women with $60,000 in student debt were 42% less likely to have children than their non-indebted peers, after controlling for education, class background, and demographic indicators. Women hold about two-thirds of student loan debt, according to the American Association of University Women.

Borrowers’ hesitancy to start families is contributing to a falloff in births in the U.S., where fertility rates have hit their lowest level in half a century. A declining birth rate can cause an aging population, a smaller workforce and tax base, and the risk of unfunded pension liabilities. In that sense, the burden of student debt isn’t just dashing the dreams of some hopeful parents—it’s a macroeconomic shock that could be felt for generations.

U.S. student loans skyrocket; birth rate sinks

Sociologist Arielle Kuperberg, 40, began researching how student debt shapes young people’s transitions to adulthood when she saw how crippling loan burdens compelled friends of hers to make difficult choices in their personal lives. One retreated to his mother’s basement after college to save on rent and pay back his loans, which made it hard for him to date throughout his twenties and thirties. Another friend with over $100,000 in student loan debt wants to have a child, but doesn’t think she can afford to.

Analyzing national loan data, Kuperberg and fellow sociologist Joan Maya Mazelis discovered these were not merely anecdotes. They found that among women born in the early 1980s with college degrees, 60% of women who had ever taken out student loans had children by age 40, compared to 67.5% who did not borrow. That 7.5-percentage-point gap is “huge in fertility terms,” said Kuperberg—amounting to some 715,000 women of prime reproductive age. “You're looking at, is this generation replacing themselves or not?” Apparently not: In the U.S., the fertility rate hit 1.64 births per woman in 2020, its lowest level since the 1970s; that same year, the country’s cumulative student loan debt reached nearly $1.7 trillion. A survey by Kuperberg and Mazelis of nearly 3,000 undergraduates from two midsize public universities in the Northeast and Southeast, showed that 47% believed people shouldn’t have kids if they had outstanding loan debt.

American millennials are not alone in their collective hesitation to reproduce. About half the world’s population lives in countries with average fertility rates (the number of children a woman can expect to have in her lifetime) below 2.1, the replacement level to keep a population stable. But the U.S. is unique in how indebted its college graduates are, thanks to decades of defunding public higher education and rising tuition costs that have left families responsible for annual tuition bills that start in the five figures.

America is also unique among wealthy countries in its lack of national paid family leave and in how little state aid it offers families. This leaves individuals cobbling together savings to take time off after a birth or to begin shelling out for childcare.

Kuperberg and Mazelis think about this state of affairs in terms of tradeoffs. “It's increasingly become an economic situation where you can have one thing, but not all the things,” Kuperberg said. “Family, economic security, a college degree, or not a lot of debt—you can only get one or two of those.”

Elliot Kindler, 34, is going with economic security for now. He graduated from Emory University in 2011 with a degree in religion and $40,000 in debt. In an economy still recovering from the financial crisis, the best job he could find was at Bank of America, which had acquired the mortgage lender Countrywide Financial. He lived at home, paying down his debt on a $37,000 salary, and processing foreclosures—“a pretty miserable three years of my life,” he recalls. Kindler saw a graduate degree as the only route “to basically make myself employable.” An MBA might saddle him with additional debt, but it would set him up to earn well for the long term. His bet paid off: An MBA at the University of Pittsburgh resulted in another $60,000 in debt but also landed him a job making $105,000 at Deloitte. He later moved to a corporate finance job with a cybersecurity firm in Northern Virginia that was acquired by Google. Now a Google employee, he makes upwards of $200,000, including equity and bonuses.

Along the way, he met his wife, a public school teacher whose roughly $85,000 in loans he learned about after they were married. Penny-pinching has brought their combined balance down to $78,000 from an original $185,000. Kindler is proud of himself for going from earning $37,000 a year to more than $200,000 ten years on. “But at the same time, those student loans haven't gone away,” he said. Their remaining debt requires nearly a $2,000 monthly payment, which is more than the $1,600 a month that he estimates childcare costs in Northern Virginia.

The couple’s earnings in 2020 and 2021 qualify them for Biden’s loan forgiveness plan, and his wife, as a government employee, is eligible for a separate forgiveness plan for workers in the public or nonprofit sector. Those programs eventually will relieve them of about $45,000 in federal debt, “depending on political forces,” Kindler notes. He estimates they could pay off the remainder in three or four years. By then, they’ll both be 37 or 38, bringing them to “the choice of do you go for one, or zero children?” Hoping to sound positive, I brought up Google’s generous fertility benefits. Kindler is aware of them, but feels as if they’re designed to encourage people to work more and put off having kids until they’ll need medical help. (Similar critiques have been made by observers and by tech workers themselves since the mid-2010s, when Big Tech companies began offering egg freezing to employees.) “I don't want to say it's a bad thing. I think it's great that they have those rewards. It's just—you know, nothing's ever completely altruistic.”

Kindler’s brother, a doctor, is two years younger and earns as much as he does. But because his brother works for a hospital system that is technically a nonprofit, he will soon be eligible for loan forgiveness. In January, his brother announced that he and his wife are expecting.

Borrowing more to earn more

Joy was lucky to land a good job with only her undergraduate degree. But like Kindler, many young people take on additional debt for an advanced degree to get farther in competitive fields. After “multiple jobs and multiple unemployments” in the nonprofit sector, Danny Navarro realized his only way to get ahead was to earn a master’s in public administration. One of the cheaper offerings in the D.C. area, at George Mason University, still necessitated $70,000 in loans. “The higher salaries required master’s degrees, but then it feels like a rat race trying to pay off these loans just to earn an extra $20,000,” says Navarro, 34, who still works in the nonprofit sector. “We now have to spend almost a quarter of our monthly income paying something back.”

His wife, Laurie Navarro, who works in public affairs for the U.S. government, was the oldest of five children born to agricultural worker parents in rural Washington state. She always thought she’d have four kids of her own. But today, at 37, she’s no longer sure that’s realistic, even less so since she was diagnosed with unexplained infertility in 2020. A gigantic pile of student debt—her $70,000 and Danny’s more than $25,000—stands in the way.

Without debt, “we would be able to focus our money on adoption or IVF,” he says.

Natasha Quadlin, an associate professor of sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has studied student loan debt, noted that women with student debt presumably attended university, and college-educated women already tend to have children at later ages. “If college-educated women further delay their fertility because of debt, they may face further fertility challenges and other pregnancy-related complications. In short, debt forgiveness may amount to removing an important barrier to fertility for some women,” Quadlin added.

Companies offer student loan relief

If the costs of student debt are causing young people to delay or forgo children, what solutions could address their concerns? Biden’s forgiveness plan would certainly help many people feel more comfortable moving ahead with their family plans—about two-thirds of older millennials have student debt loads of $20,000 or less, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

“Having children in the U.S. is enormously expensive, and any disposable income freed up through debt forgiveness can be redirected toward investments in the future generation,” Quadlin said.

But for borrowers with hefty balances, that might not be enough to make a difference. Plus, the political and legal uncertainty surrounding policy initiatives that might help families makes it hard to grasp one’s future finances, said Suzanne Kahn, managing director of research and policy at the Roosevelt Institute, a left-leaning think tank. Student loan forgiveness and an expanded child tax credit are “incredibly welcome and badly needed support for folks trying to start a family,” but, she added, “You need to be able to assume they will stay in place. So it just strikes me as really tragic that between the Supreme Court and Congress, that's really difficult to do for a whole range of policies.”

Over the past two decades, various states have enacted paid family plans, and at the federal level, the recently introduced Child Care for Every Community Act, co-sponsored by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) and Reps. Mikie Sherrill (D–N.J.) and Sara Jacobs (D–Calif.), would cap childcare costs at 7% of total income for high-earning families, while half of American families would pay $10 a day or less for care.

Corporations are aware of workers’ desires to have families. Tech firms began offering egg-freezing benefits in 2014, and today 54% of large companies cover in vitro fertilization, according to a 2022 survey of employer health plans by the management consulting firm Mercer. But help covering the recurring cost of childcare, which ranges from $5,436 a year for infant care in Mississippi to $24,243 in Washington, D.C., is less common. One rare exception is outdoor apparel company Patagonia, which has provided on-site childcare at its headquarters since 1983.

Other companies have started to take their workers’ student loans seriously. Google announced a $2,500 annual loan repayment benefit in 2020; PwC offers up to $10,000 in total repayment assistance. Such benefits help companies attract talent. A Mercer survey of more than 4,000 workers conducted in 2022 found that employer matching for paying down student debt was the second most popular defined contribution plan benefit they’d like their company to offer, behind an increase in employer matching for retirement. For workers under 45, it was the top choice.

“Loving what you do”—or reducing loans?

Rachel Blomquist would love to work for a company that assisted its workers with student loans or childcare costs. “That would have a huge impact on my decision to where I would go,” she said. The 34-year-old, who works as a user experience designer at an education technology firm, holds $177,400 in student debt: around $20,000 for an undergrad in anthropology from Creighton University and over $148,000 for a master’s in East Asian studies at Georgetown University, plus about $10,000 in interest.

I asked whether she had grasped the magnitude of the loans she was taking out for her master’s degree. At the time, she was hoping to go into nonprofit work in international development, and qualify for public service loan forgiveness after 10 years. “I just—I glazed over the numbers, because I can't process that,” she said. She had also become accustomed to thinking of her loan obligations in terms of a percentage of her monthly pay, not in their entirety. “In my mind I can say, ‘Oh, well, I’ll just pay 10% of my income for the next 25 years. I can do that.”

It wasn’t until she got married in 2020 that her month-to-month approach became untenable. Her monthly minimum payment soon will jump from $300 to $900 based on her and her husband’s combined income. She and her husband would like to eventually have at least one kid—maybe two—and now she finally feels psychologically ready. But, she said, “I still don't feel financially ready because of the student loans…where I am personally, financially is very precarious, even having one child. Definitely, I do not think I'll be able to afford two kids.”

Having $20,000 forgiven through the Biden plan would bring her balance down to $150,000—“a nice, clean number,” she says—and one that she is now trying to think about more holistically, as something to tackle in its entirety. “I actually have been thinking more about, How can I pay it off? How can I just get rid of this debt?” she said. “But there's no mechanism in existence that would actually allow me to pay it off.” If they do have kids, she wonders what she would tell them about student loans. “I would want to raise my kid in a similar way that I was raised—to do what you love,” she said. “But my student loans tell me not to do what I love.”

This story was produced with the support of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.