购物中心里的大多数顾客都没有意识到,美国这家无处不在的大型珠宝连锁店拥有各自不同的目标群体。例如,Zales主打时尚和潮流以及个人礼物,也就是那些人们可能在办公室或者参加邻居普通聚会时穿戴的饰品。如果人们想购买一些不同寻常的首饰,比如给纪念日或者订婚这类重大庆祝活动的主角送礼,那么他们就更有可能去光顾Kay。如果人们大幅提升其购物预算,而且将目光瞄向了准奢华珠宝,愿意花费3,000美元或者更多的资金,他们可能就会离开商场,并前往附近出售高端珠宝的Jared。

还有一个情况大多数购物者同样不怎么了解,那就是所有这三家连锁店(每一个品牌在美国境内都有数百家店面)都归属于同一家公司Signet Jewelers。这家珠宝零售巨头的总部位于美国俄亥俄州,成立于百慕大。这家公司之所以能够东山再起,Signet的长期董事、消费品业务资深人士吉娜·德罗索斯可谓是功不可没,她于2017年开始担任该公司的首席执行官。

需要强调的是,德罗索斯在Zoom的记者电话会议上佩戴的始终都是Zales的首饰。德罗索斯用略带南方拖腔的口音说:“我非常欣赏将首饰作为时尚物品的理念,以及人们搭配和叠戴不同的首饰的方式。”她抚摸着自己脖子上三条组合金项链解释说,Zales的咨询师为其提供了穿搭建议,因为她希望自己佩戴的首饰可以兼顾潮流与职业。

Signet帝国或许并非一直走在时尚前沿,然而,自从德罗索斯这位公司的首位女性首席执行官执掌之后,Signet如今的发展态势比过去强劲了不少。不久之前,Signet旗下三大连锁品牌甚至连自己的目标群体都不是很清楚。确实,自Signet在21世纪10年代陷入低谷之后,其最大的三个品牌开始内卷,而且各自的差异化特征几乎消失殆尽。德罗索斯回忆道,当时,Zales的任何促销活动都会导致Kay业务量下滑。由于这些品牌的连锁店通常互为竞争关系,而且在同一层级的商场中距离很近,上述问题也就变得更加严重。德罗索斯说:“公司旗下的几个品牌基本都在中端市场相互掐架。”

Signet的三大顶级品牌贡献了该公司77%的销售额,其各自定位的明确划分只不过是这位首席执行官长篇工作清单中的一项任务罢了。虽然说Signet是美国最大的专业珠宝商,但在德罗索斯接手时,这家公司却面临着一系列严峻问题。Signet在2014年收购的品牌Zales其实是一个陷阱,这家零售商负债累累,而且业绩不佳的店面比比皆是,客户和供应商对其都没有什么好感。Signet的资产负债表则受累于其店面信用卡业务,而且电商业务基本就是一个摆设。更为严重的是,公司爆出了大量的性别歧视和性骚扰案件,其影响最终导致了德罗索斯前任的离职。

到目前为止,德罗索斯重构Signet的计划已经获得不小的成功,而这一策略源于她在宝洁(Procter & Gamble)数十年的经验,以及她在一家基因测试初创企业担任首席执行官的履历。Signet关闭了Kay和Zales旗下数百家经营不善的店面,并减少了其对折扣的依赖,同时出售了信用卡业务。得益于在2022年收购的零售网站Blue Nile以及租赁服务Rocksbox,它终于跟上了电商时代的步伐。德罗索斯已经开始着手改变Signet的文化。为实现这一点,她确保那些如惊弓之鸟的雇员,尤其是女性,能够获得倾听和参与感,并且愿意相信管理层的愿景,此外,她还对董事会进行了大刀阔斧的改革。

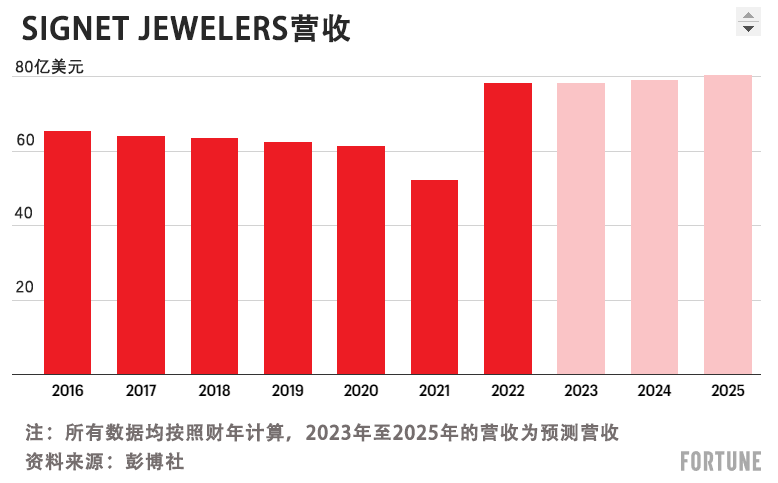

Signet的销售额在2021年达到了78亿美元,比德罗索斯上任第一年增长了22%,较其在新冠疫情期间的低谷增长了50%,并创下了新高。2022年12月中旬,Signet的第三季度销售额和利润均高于预期,有力地支撑了德罗索斯的成功宣言。

与此同时,Signet的挑战可谓是接踵而至。销售额受到了通胀的冲击,因为客户削减了对珠宝的开支,这项自主性的支出就像是人间蒸发了一样。Kay、Zales,甚至是Jared的消费群体与蒂芙尼(Tiffany)不一样,跟卡地亚(Cartier)就更无法比了。毕竟,这类群体不大可能在不景气的时期花费大量资金来购买首饰。WSL Strategic Retail的首席执行官温迪·利布曼表示:“美国中低端珠宝市场遭遇了巨大的压力。我们走出了新冠疫情的阴影,却陷入了通胀,这时人们会说:‘我真的需要珠宝吗?’”

假日季已经早早地回答了这个问题:Signet的30%的年度销售额通常来自于11月和12月。然而,不管珠宝购买人群是感到不安,还是信心十足,或者介于两者之间,Signet依然有很多工作需要做,更何况华尔街预计Signet的销售业绩在未来两年之内不大可能会出现增长,Signet也就更加任重道远了。

德罗索斯的计划将不得不侧重于:通过超越其竞争对手赢得更多的市场份额;进一步实现业务的多元化;继续专注于电商业务,以防止其再次停滞不前。德罗索斯说:“我们过去奉行的老办法在上一个十年发挥了其作用。我们当时更加关注商品,与供应商合作,而不是倾听消费者的心声。”问题在于,新的战略和新的文化是否可以让Signet在波涛汹涌的市场中站稳脚跟。

这家规模最大的珠宝商仍然具有增长空间

Signet所处的战场是一个高度细分化的市场,占据主导地位的多是小型区域连锁店和独立经销商。尽管该公司是美国最大的珠宝商,但其份额仅占到这个价值760亿美元市场的9.3%。这家公司的规模源于自身160年以来的珠宝行业并购交易。

Signet公司的资产组合起源于1862年成立的英国珠宝商H. Samuel。20世纪80年代,H. Samuel被英国巨头和美国区域连锁店Ratner Jewelers吞并,后者在那一时期又收购了Sterling Jewelers。1993年,Ratner更名为Signet。如今,Kay(此前是Sterling帝国的支柱品牌)、Zales和Jared三大品牌的销售额分别占Signet总销售额的38%、22%和17%。Signet还收购了Banter by Piercing Pagoda,后者是商场里的固定摊位,也是无数美国人第一次打耳眼的地方。Signet的6%的销售额来自于英国和爱尔兰,3%来自于加拿大,剩下的则来自美国。

得益于其规模,Signet数十年来一直在市场上处于主导地位,但与众多行业领袖一样,该公司出现了僵化现象。事后来看,公司2014年对其竞争对手Zale Corp.的收购似乎成为了一个经典案例,即公司通过花钱来购买自身无法实现的有机增长。该交易为Signet带来了更多的债务,而且该连锁店存在大量需要翻修的实体店面,同时其地域分布和款式与Kay高度重合。这个战略性的问题很快便波及了销售额:Signet的总销售额在截至2016年年初的财年达到了65.5亿美元的峰值,然而在接下来的五年中不断下滑,经营利润也因此江河日下。

德罗索斯正是在这一时刻挺身而出。她自2012年便担任Signet董事,曾经在宝洁工作了25年的时间,并升任其美妆业务负责人。她随后进军生物科技初创领域,担任基因测试公司Assurex Health的首席执行官,并执掌该公司四年时间,直到其被收购。德罗索斯表示,这段经历让她更加深刻地意识到数据对决策的作用。事实证明,这一认知对于她的新岗位至关重要。

摆在她眼前的其中一个显而易见的首要解决办法就是削减Kay和Zales连锁店的数量。德罗索斯最终关闭了1,250家店面,同时在更好的地段新开了400家店面,主要涉及Kay和Zales这两个最大的品牌。总的来说,她关闭了Signet的20%的实体店面,如今其美国店面数量为2,500家。

德罗索斯还通过加大对客户的研究力度来为其改革提供指引。尽管消费者一直在告诉Signet自己已经做好了在线购物的准备,但没有得到管理层的真正重视。珠宝购买是零售行业抗拒电商最后的堡垒之一,而Signet在此前却并不怎么重视这个机会。[蒂芙尼在电商方面也是行动迟缓;自两年前收购蒂芙尼之后,路威酩轩(LVMH)的首要任务便是把这家奢华珠宝商发展成为电商业务的巨头。]

这位新首席执行官意识到,电商不仅仅是创建一个促进交易的网站,同时还要让人们能够在进店前对其产品进行甄选。她在担任首席执行官之后首先采取的一个举措便是于2017年收购了JamesAllen.com,不仅仅是因为该网站有着庞大的业务,同时还因为它拥有有望颠覆钻石行业的技术,这项技术可以生成网站上所有贩卖宝石的360度高分辨率影像,同时还能够创建一个虚拟展示厅,为买家提供数万枚钻石进行挑选。如今,这一技术也可以被用于Jared和Kay的网站。德罗索斯称:“如今,人们能够在网站上更好地观赏钻石,而且比在店面更清楚,因为我们可以将其放大,并以高分辨率图像展示。”

科技还能够通过新奇的方式发挥作用,尤其是库存管理方面。如果劳德代尔堡的店面的一枚戒指无人问津,那么明尼那波利斯的销售人员便可以将其销售给客户。所有这一切意味着商品的周转会变得更快,也就会给店面带来更多的新商品,而“新款”则会吸引客户,并维持业务的利润率。

有鉴于新冠疫情带来的巨大威胁,将电商作为业务重点最终为公司带来了好运。2020年年中,Signet一直都在应对春末关闭店面数周所带来的影响,毕竟,Zales、Kay和Jared都不是必需品零售商。Signet不顾一切的想要确保营收不会大幅下滑,并加速采用虚拟销售和路边取货等方式来迎合不愿意与其他人密切接触的消费者。公司2020年的总销售额下滑了15%,但这段经历为Signet提供了一些宝贵的新力量。2017年,Signet的线上销售额占比约为5%,如今这一比例达到了23%。

收购线上珠宝零售商James Allen的交易也反映了Signet并购策略的转变。公司长期以来一直专注于收购实体竞争对手;如今,它更关注于构建其电商业务的交易,或至少能够获得新客户的交易。这一举措的核心人物便是琼·希尔森,此前供职于维多利亚的秘密(Victoria’s Secret),自20世纪80年代开始为Signet效力,德罗索斯于2018年聘请她担任公司的策略与财务主管。

德罗索斯和希尔森的一个宏大目标就是解决Signet资产负债表存在的高杠杆问题,并通过削减Signet经营构架的成本来提振盈利能力。自2017年以来,Signet将其长期债务削减了80%,降至1.47亿美元,公司2021年的经营利润率为11.6%,是三年前的两倍多。这一更加强劲的现金流让Signet能够放心大胆地开展收购业务。希尔森说:“此举为公司带来了拓展市场的流动性,并让公司发展壮大。”

公司收购了德罗索斯关注了数年的Blue Nile。作为首个大型专业线上珠宝零售商,Blue Nile在10年前便引发了业界的轰动。然而,该品牌始终未能一飞冲天,其最高的年营收为5亿美元。Signet在2022年9月以3.6亿美元的现金收购了该公司,拿下了这个有着出众虚拟展示厅以及不俗年轻客户群的电商网站。Signet在2022年还完成了对租赁公司Rocksbox、小型专营连锁店Diamonds Direct,以及帮助Signet提供保养和估值服务的多家公司的收购。

这一系列收购交易让Signet这个巨头越发庞大。该公司旗下的零售品牌从2017年的8个增至如今的11个。这一现象也引发了一个新问题:Signet是否可以保持这些品牌不断增长,而且不会让顾客感到困惑或者引发品牌之间的内卷。零售分析师利布曼表示:“这些品牌的数量着实不少。如果不小心的话,就很有可能会导致自身业务的碎片化和相互吞噬。”不过到目前为止,公司的三大连锁品牌Kay、Jared和Zales都再次恢复增长,主要原因在于德罗索斯的团队能够下决心去关闭那些应该关闭的店面。

应对有害的公司文化

如果没有改变Signet的文化,德罗索斯也就无法实现Signet的翻身。与众多零售商一样,Signet一直都是一家以女性员工和女性客户为主的公司,但领导层大多数都是男性。在德罗索斯担任首席执行官时,这种格局变得难以为继。

在《华盛顿邮报》(Washington Post)2017年2月一则令人极为震惊的报道发布之后,转折点出现了。当时,这则报道称性骚扰在Signet已经成为一种猖獗的系统性现象,而且从上到下的男性主管皆是如此。该报道明确提到了2014年担任Signet首席执行官的Signet终身员工马克·莱特。除了其他的指控之外,报道称有人看到莱特在企业活动中与“全裸和半裸的女性雇员”待在泳池里。莱特和Signet一再否认这项指控。然而,莱特以未详细说明的健康问题为由,于2017年夏季离开了公司。与此同时,其他有牵连的经理也相继离职。2022年,Signet和解了有关起诉公司在招聘和薪酬制度中存在性别歧视的集体诉讼案,并向6.8万名现任和前雇员赔偿了1.75亿美元。

这种有害的文化并非只涉及猖獗的品行不端行为,它还滋生了业务方面的独断专行,以男性为主导的管理者们并不会倾听现场员工所反映的问题,也就是Signet以女性为主导的员工。德罗索斯称,自2012年成为公司董事以来,她一直在推动Signet员工和文化的多元化举措。她表示,在她担任首席执行官之后,董事会让其加速这一举措。

修复充满恐惧和厌恶风险的文化是一件异常困难的事情。德罗索斯说:“这也是在接受这份工作时令我感到最紧张的事情之一。”她最先采取的其中一个举措就是,将多元化和包容性目标融入每一位管理者的评估指标,并制定了性骚扰零容忍政策。她回忆道:“我打算从零开始。我不会重蹈覆辙。”如今,42%的副总裁级别以上雇员都是女性,在店面层面,76%的副经理以上职员都是女性。她指出:“这个水平的占比让所有雇员对未来的可能性充满了憧憬。”

另一个重要的拯救措施是,将更多的自主权和管理权限下放至店面。当德罗索斯开始担任首席执行官时,她让各个店面召开团队会议,甚至倾听客户服务电话,从而了解都有哪些需要真正改进的问题。德罗索斯表示:“我很快意识到,公司的文化基本上是自上而下的命令与控制。公司内部并不缺乏人才,我们需要做的就是释放其才干。”店面经理如今对于Signet连锁店的销售商品拥有更大的话语权。这一举措,结合重叠店面的关闭,帮助大幅提升了单店销售额:Signet店面平均年销售额较新冠疫情前提升了50%。

这一成功的策略反映了德罗索斯自身的历史:她称,自己在宝洁工作的25年期间,有求必应的高层给予的支持让其获益匪浅。她提到了其导师雷富礼(A.G. Lafley),这位传奇般的首席执行官曾经在21世纪初领导这家消费巨头东山再起。正是在宝洁的经历让德罗索斯懂得了对一线信息进行快速响应的重要性。她将这些洞见转化为行动,并因为领导知名护肤品牌玉兰油(Olay)重振雄风而声名鹊起。

由于深入掌握了令宝洁得以成名的市场数据,德罗索斯看到了存在于奢华高价百货店品牌与低价药店品牌之间的护肤市场。玉兰油在沃尔玛(Walmart)或者CVS的单品售价均不超过10美元。她回忆道:“这中间存在着巨大的空白。”因此,她打造了25美元的保湿霜,并称其品质可以与在尼曼百货(Neiman Marcus)售价数百美元的奢华美容品牌海蓝之谜(La Mer)媲美。这一豪赌得到了回报:在其卸任时,玉兰油的年销售额从其执掌伊始的2.5亿美元增至25亿美元。德罗索斯说:“这一切完全在于理解消费者的需求,并打造能够为自身带来竞争优势的颠覆性产品。”

起伏不定的未来经济走向

尽管Signet最近大获成功,但宏观经济一直在提醒德罗索斯及其团队他们所取得的成就有多脆弱。在最近的一个季度中,Signet同比销售或业务,不计新开设或关闭店面和业务单元的影响,下滑了7.6%。这个成绩基本上是必然的,因为在一年前,新冠疫情缓解之后,销售业绩曾经出现了大幅回弹。不管怎么样,华尔街预计未来三年该公司的销售增速将非常有限。分析师预计其年销售额届时将在80亿美元附近徘徊。

为了挺过日趋疲软的经济环境,公司将不得不继续遵循德罗索斯密切关注客户需求的策略。公司在2022年进一步提升了Jared的档次,并调高了售价,同时,Kay将更密切地关注婚礼珠宝,Zales则主打时尚。分析师称,类似举动将有助于保护其市场份额和利润率。GlobalData的董事总经理尼尔·桑德斯表示:“在调整其产品种类、服务和营销来更好地迎合消费者方面,Signet还是可圈可点的。”

德罗索斯在2022年尝试了Signet的婚礼戒指服务,她与James Allen的员工一道在2021年自己的婚礼之前设计了其订婚戒指。这枚戒指采用了20世纪30年代的意大利装饰艺术设计。她回忆道:“一开始,他们并没有找到可以让其感到足够自豪的镶嵌钻石,因此他们让我等了一段时间。”等待是值得的,她说:“我自己也算是一个前卫高调的人。”(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

购物中心里的大多数顾客都没有意识到,美国这家无处不在的大型珠宝连锁店拥有各自不同的目标群体。例如,Zales主打时尚和潮流以及个人礼物,也就是那些人们可能在办公室或者参加邻居普通聚会时穿戴的饰品。如果人们想购买一些不同寻常的首饰,比如给纪念日或者订婚这类重大庆祝活动的主角送礼,那么他们就更有可能去光顾Kay。如果人们大幅提升其购物预算,而且将目光瞄向了准奢华珠宝,愿意花费3,000美元或者更多的资金,他们可能就会离开商场,并前往附近出售高端珠宝的Jared。

还有一个情况大多数购物者同样不怎么了解,那就是所有这三家连锁店(每一个品牌在美国境内都有数百家店面)都归属于同一家公司Signet Jewelers。这家珠宝零售巨头的总部位于美国俄亥俄州,成立于百慕大。这家公司之所以能够东山再起,Signet的长期董事、消费品业务资深人士吉娜·德罗索斯可谓是功不可没,她于2017年开始担任该公司的首席执行官。

需要强调的是,德罗索斯在Zoom的记者电话会议上佩戴的始终都是Zales的首饰。德罗索斯用略带南方拖腔的口音说:“我非常欣赏将首饰作为时尚物品的理念,以及人们搭配和叠戴不同的首饰的方式。”她抚摸着自己脖子上三条组合金项链解释说,Zales的咨询师为其提供了穿搭建议,因为她希望自己佩戴的首饰可以兼顾潮流与职业。

Signet帝国或许并非一直走在时尚前沿,然而,自从德罗索斯这位公司的首位女性首席执行官执掌之后,Signet如今的发展态势比过去强劲了不少。不久之前,Signet旗下三大连锁品牌甚至连自己的目标群体都不是很清楚。确实,自Signet在21世纪10年代陷入低谷之后,其最大的三个品牌开始内卷,而且各自的差异化特征几乎消失殆尽。德罗索斯回忆道,当时,Zales的任何促销活动都会导致Kay业务量下滑。由于这些品牌的连锁店通常互为竞争关系,而且在同一层级的商场中距离很近,上述问题也就变得更加严重。德罗索斯说:“公司旗下的几个品牌基本都在中端市场相互掐架。”

Signet的三大顶级品牌贡献了该公司77%的销售额,其各自定位的明确划分只不过是这位首席执行官长篇工作清单中的一项任务罢了。虽然说Signet是美国最大的专业珠宝商,但在德罗索斯接手时,这家公司却面临着一系列严峻问题。Signet在2014年收购的品牌Zales其实是一个陷阱,这家零售商负债累累,而且业绩不佳的店面比比皆是,客户和供应商对其都没有什么好感。Signet的资产负债表则受累于其店面信用卡业务,而且电商业务基本就是一个摆设。更为严重的是,公司爆出了大量的性别歧视和性骚扰案件,其影响最终导致了德罗索斯前任的离职。

到目前为止,德罗索斯重构Signet的计划已经获得不小的成功,而这一策略源于她在宝洁(Procter & Gamble)数十年的经验,以及她在一家基因测试初创企业担任首席执行官的履历。Signet关闭了Kay和Zales旗下数百家经营不善的店面,并减少了其对折扣的依赖,同时出售了信用卡业务。得益于在2022年收购的零售网站Blue Nile以及租赁服务Rocksbox,它终于跟上了电商时代的步伐。德罗索斯已经开始着手改变Signet的文化。为实现这一点,她确保那些如惊弓之鸟的雇员,尤其是女性,能够获得倾听和参与感,并且愿意相信管理层的愿景,此外,她还对董事会进行了大刀阔斧的改革。

Signet的销售额在2021年达到了78亿美元,比德罗索斯上任第一年增长了22%,较其在新冠疫情期间的低谷增长了50%,并创下了新高。2022年12月中旬,Signet的第三季度销售额和利润均高于预期,有力地支撑了德罗索斯的成功宣言。

与此同时,Signet的挑战可谓是接踵而至。销售额受到了通胀的冲击,因为客户削减了对珠宝的开支,这项自主性的支出就像是人间蒸发了一样。Kay、Zales,甚至是Jared的消费群体与蒂芙尼(Tiffany)不一样,跟卡地亚(Cartier)就更无法比了。毕竟,这类群体不大可能在不景气的时期花费大量资金来购买首饰。WSL Strategic Retail的首席执行官温迪·利布曼表示:“美国中低端珠宝市场遭遇了巨大的压力。我们走出了新冠疫情的阴影,却陷入了通胀,这时人们会说:‘我真的需要珠宝吗?’”

假日季已经早早地回答了这个问题:Signet的30%的年度销售额通常来自于11月和12月。然而,不管珠宝购买人群是感到不安,还是信心十足,或者介于两者之间,Signet依然有很多工作需要做,更何况华尔街预计Signet的销售业绩在未来两年之内不大可能会出现增长,Signet也就更加任重道远了。

德罗索斯的计划将不得不侧重于:通过超越其竞争对手赢得更多的市场份额;进一步实现业务的多元化;继续专注于电商业务,以防止其再次停滞不前。德罗索斯说:“我们过去奉行的老办法在上一个十年发挥了其作用。我们当时更加关注商品,与供应商合作,而不是倾听消费者的心声。”问题在于,新的战略和新的文化是否可以让Signet在波涛汹涌的市场中站稳脚跟。

这家规模最大的珠宝商仍然具有增长空间

Signet所处的战场是一个高度细分化的市场,占据主导地位的多是小型区域连锁店和独立经销商。尽管该公司是美国最大的珠宝商,但其份额仅占到这个价值760亿美元市场的9.3%。这家公司的规模源于自身160年以来的珠宝行业并购交易。

Signet公司的资产组合起源于1862年成立的英国珠宝商H. Samuel。20世纪80年代,H. Samuel被英国巨头和美国区域连锁店Ratner Jewelers吞并,后者在那一时期又收购了Sterling Jewelers。1993年,Ratner更名为Signet。如今,Kay(此前是Sterling帝国的支柱品牌)、Zales和Jared三大品牌的销售额分别占Signet总销售额的38%、22%和17%。Signet还收购了Banter by Piercing Pagoda,后者是商场里的固定摊位,也是无数美国人第一次打耳眼的地方。Signet的6%的销售额来自于英国和爱尔兰,3%来自于加拿大,剩下的则来自美国。

得益于其规模,Signet数十年来一直在市场上处于主导地位,但与众多行业领袖一样,该公司出现了僵化现象。事后来看,公司2014年对其竞争对手Zale Corp.的收购似乎成为了一个经典案例,即公司通过花钱来购买自身无法实现的有机增长。该交易为Signet带来了更多的债务,而且该连锁店存在大量需要翻修的实体店面,同时其地域分布和款式与Kay高度重合。这个战略性的问题很快便波及了销售额:Signet的总销售额在截至2016年年初的财年达到了65.5亿美元的峰值,然而在接下来的五年中不断下滑,经营利润也因此江河日下。

德罗索斯正是在这一时刻挺身而出。她自2012年便担任Signet董事,曾经在宝洁工作了25年的时间,并升任其美妆业务负责人。她随后进军生物科技初创领域,担任基因测试公司Assurex Health的首席执行官,并执掌该公司四年时间,直到其被收购。德罗索斯表示,这段经历让她更加深刻地意识到数据对决策的作用。事实证明,这一认知对于她的新岗位至关重要。

摆在她眼前的其中一个显而易见的首要解决办法就是削减Kay和Zales连锁店的数量。德罗索斯最终关闭了1,250家店面,同时在更好的地段新开了400家店面,主要涉及Kay和Zales这两个最大的品牌。总的来说,她关闭了Signet的20%的实体店面,如今其美国店面数量为2,500家。

德罗索斯还通过加大对客户的研究力度来为其改革提供指引。尽管消费者一直在告诉Signet自己已经做好了在线购物的准备,但没有得到管理层的真正重视。珠宝购买是零售行业抗拒电商最后的堡垒之一,而Signet在此前却并不怎么重视这个机会。[蒂芙尼在电商方面也是行动迟缓;自两年前收购蒂芙尼之后,路威酩轩(LVMH)的首要任务便是把这家奢华珠宝商发展成为电商业务的巨头。]

这位新首席执行官意识到,电商不仅仅是创建一个促进交易的网站,同时还要让人们能够在进店前对其产品进行甄选。她在担任首席执行官之后首先采取的一个举措便是于2017年收购了JamesAllen.com,不仅仅是因为该网站有着庞大的业务,同时还因为它拥有有望颠覆钻石行业的技术,这项技术可以生成网站上所有贩卖宝石的360度高分辨率影像,同时还能够创建一个虚拟展示厅,为买家提供数万枚钻石进行挑选。如今,这一技术也可以被用于Jared和Kay的网站。德罗索斯称:“如今,人们能够在网站上更好地观赏钻石,而且比在店面更清楚,因为我们可以将其放大,并以高分辨率图像展示。”

科技还能够通过新奇的方式发挥作用,尤其是库存管理方面。如果劳德代尔堡的店面的一枚戒指无人问津,那么明尼那波利斯的销售人员便可以将其销售给客户。所有这一切意味着商品的周转会变得更快,也就会给店面带来更多的新商品,而“新款”则会吸引客户,并维持业务的利润率。

有鉴于新冠疫情带来的巨大威胁,将电商作为业务重点最终为公司带来了好运。2020年年中,Signet一直都在应对春末关闭店面数周所带来的影响,毕竟,Zales、Kay和Jared都不是必需品零售商。Signet不顾一切的想要确保营收不会大幅下滑,并加速采用虚拟销售和路边取货等方式来迎合不愿意与其他人密切接触的消费者。公司2020年的总销售额下滑了15%,但这段经历为Signet提供了一些宝贵的新力量。2017年,Signet的线上销售额占比约为5%,如今这一比例达到了23%。

收购线上珠宝零售商James Allen的交易也反映了Signet并购策略的转变。公司长期以来一直专注于收购实体竞争对手;如今,它更关注于构建其电商业务的交易,或至少能够获得新客户的交易。这一举措的核心人物便是琼·希尔森,此前供职于维多利亚的秘密(Victoria’s Secret),自20世纪80年代开始为Signet效力,德罗索斯于2018年聘请她担任公司的策略与财务主管。

德罗索斯和希尔森的一个宏大目标就是解决Signet资产负债表存在的高杠杆问题,并通过削减Signet经营构架的成本来提振盈利能力。自2017年以来,Signet将其长期债务削减了80%,降至1.47亿美元,公司2021年的经营利润率为11.6%,是三年前的两倍多。这一更加强劲的现金流让Signet能够放心大胆地开展收购业务。希尔森说:“此举为公司带来了拓展市场的流动性,并让公司发展壮大。”

公司收购了德罗索斯关注了数年的Blue Nile。作为首个大型专业线上珠宝零售商,Blue Nile在10年前便引发了业界的轰动。然而,该品牌始终未能一飞冲天,其最高的年营收为5亿美元。Signet在2022年9月以3.6亿美元的现金收购了该公司,拿下了这个有着出众虚拟展示厅以及不俗年轻客户群的电商网站。Signet在2022年还完成了对租赁公司Rocksbox、小型专营连锁店Diamonds Direct,以及帮助Signet提供保养和估值服务的多家公司的收购。

这一系列收购交易让Signet这个巨头越发庞大。该公司旗下的零售品牌从2017年的8个增至如今的11个。这一现象也引发了一个新问题:Signet是否可以保持这些品牌不断增长,而且不会让顾客感到困惑或者引发品牌之间的内卷。零售分析师利布曼表示:“这些品牌的数量着实不少。如果不小心的话,就很有可能会导致自身业务的碎片化和相互吞噬。”不过到目前为止,公司的三大连锁品牌Kay、Jared和Zales都再次恢复增长,主要原因在于德罗索斯的团队能够下决心去关闭那些应该关闭的店面。

应对有害的公司文化

如果没有改变Signet的文化,德罗索斯也就无法实现Signet的翻身。与众多零售商一样,Signet一直都是一家以女性员工和女性客户为主的公司,但领导层大多数都是男性。在德罗索斯担任首席执行官时,这种格局变得难以为继。

在《华盛顿邮报》(Washington Post)2017年2月一则令人极为震惊的报道发布之后,转折点出现了。当时,这则报道称性骚扰在Signet已经成为一种猖獗的系统性现象,而且从上到下的男性主管皆是如此。该报道明确提到了2014年担任Signet首席执行官的Signet终身员工马克·莱特。除了其他的指控之外,报道称有人看到莱特在企业活动中与“全裸和半裸的女性雇员”待在泳池里。莱特和Signet一再否认这项指控。然而,莱特以未详细说明的健康问题为由,于2017年夏季离开了公司。与此同时,其他有牵连的经理也相继离职。2022年,Signet和解了有关起诉公司在招聘和薪酬制度中存在性别歧视的集体诉讼案,并向6.8万名现任和前雇员赔偿了1.75亿美元。

这种有害的文化并非只涉及猖獗的品行不端行为,它还滋生了业务方面的独断专行,以男性为主导的管理者们并不会倾听现场员工所反映的问题,也就是Signet以女性为主导的员工。德罗索斯称,自2012年成为公司董事以来,她一直在推动Signet员工和文化的多元化举措。她表示,在她担任首席执行官之后,董事会让其加速这一举措。

修复充满恐惧和厌恶风险的文化是一件异常困难的事情。德罗索斯说:“这也是在接受这份工作时令我感到最紧张的事情之一。”她最先采取的其中一个举措就是,将多元化和包容性目标融入每一位管理者的评估指标,并制定了性骚扰零容忍政策。她回忆道:“我打算从零开始。我不会重蹈覆辙。”如今,42%的副总裁级别以上雇员都是女性,在店面层面,76%的副经理以上职员都是女性。她指出:“这个水平的占比让所有雇员对未来的可能性充满了憧憬。”

另一个重要的拯救措施是,将更多的自主权和管理权限下放至店面。当德罗索斯开始担任首席执行官时,她让各个店面召开团队会议,甚至倾听客户服务电话,从而了解都有哪些需要真正改进的问题。德罗索斯表示:“我很快意识到,公司的文化基本上是自上而下的命令与控制。公司内部并不缺乏人才,我们需要做的就是释放其才干。”店面经理如今对于Signet连锁店的销售商品拥有更大的话语权。这一举措,结合重叠店面的关闭,帮助大幅提升了单店销售额:Signet店面平均年销售额较新冠疫情前提升了50%。

这一成功的策略反映了德罗索斯自身的历史:她称,自己在宝洁工作的25年期间,有求必应的高层给予的支持让其获益匪浅。她提到了其导师雷富礼(A.G. Lafley),这位传奇般的首席执行官曾经在21世纪初领导这家消费巨头东山再起。正是在宝洁的经历让德罗索斯懂得了对一线信息进行快速响应的重要性。她将这些洞见转化为行动,并因为领导知名护肤品牌玉兰油(Olay)重振雄风而声名鹊起。

由于深入掌握了令宝洁得以成名的市场数据,德罗索斯看到了存在于奢华高价百货店品牌与低价药店品牌之间的护肤市场。玉兰油在沃尔玛(Walmart)或者CVS的单品售价均不超过10美元。她回忆道:“这中间存在着巨大的空白。”因此,她打造了25美元的保湿霜,并称其品质可以与在尼曼百货(Neiman Marcus)售价数百美元的奢华美容品牌海蓝之谜(La Mer)媲美。这一豪赌得到了回报:在其卸任时,玉兰油的年销售额从其执掌伊始的2.5亿美元增至25亿美元。德罗索斯说:“这一切完全在于理解消费者的需求,并打造能够为自身带来竞争优势的颠覆性产品。”

起伏不定的未来经济走向

尽管Signet最近大获成功,但宏观经济一直在提醒德罗索斯及其团队他们所取得的成就有多脆弱。在最近的一个季度中,Signet同比销售或业务,不计新开设或关闭店面和业务单元的影响,下滑了7.6%。这个成绩基本上是必然的,因为在一年前,新冠疫情缓解之后,销售业绩曾经出现了大幅回弹。不管怎么样,华尔街预计未来三年该公司的销售增速将非常有限。分析师预计其年销售额届时将在80亿美元附近徘徊。

为了挺过日趋疲软的经济环境,公司将不得不继续遵循德罗索斯密切关注客户需求的策略。公司在2022年进一步提升了Jared的档次,并调高了售价,同时,Kay将更密切地关注婚礼珠宝,Zales则主打时尚。分析师称,类似举动将有助于保护其市场份额和利润率。GlobalData的董事总经理尼尔·桑德斯表示:“在调整其产品种类、服务和营销来更好地迎合消费者方面,Signet还是可圈可点的。”

德罗索斯在2022年尝试了Signet的婚礼戒指服务,她与James Allen的员工一道在2021年自己的婚礼之前设计了其订婚戒指。这枚戒指采用了20世纪30年代的意大利装饰艺术设计。她回忆道:“一开始,他们并没有找到可以让其感到足够自豪的镶嵌钻石,因此他们让我等了一段时间。”等待是值得的,她说:“我自己也算是一个前卫高调的人。”(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

Most passersby at the mall don’t realize it, but America’s big, ubiquitous jewelry store chains are designed to serve different needs. Zales, for example, is more focused on fashion and trends and gifts for oneself—the kind of jewelry you might wear to the office, or to a casual party in your neighborhood. If you were looking for something more out of the ordinary, a gift for someone to celebrate a big life event like an anniversary or an engagement, you’d probably be more likely to go to Kay. And if you were going shopping with a substantially bigger budget and dip into quasi-luxury, willing to spend, say, $3,000 or more, you might leave the mall and go to a nearby Jared, which tracks higher-end.

Another thing most shoppers don’t realize is that all three of those chains—each a national brand with hundreds of stores—are owned by the same company: Signet Jewelers, a jewelry-retail behemoth headquartered in Ohio and incorporated in Bermuda. It’s a company celebrating a resurgence, thanks in no small part to Gina Drosos, a longtime Signet board member and consumer-goods veteran who became CEO in 2017.

And for the record, the jewelry Drosos is wearing—on a Zoom call with a reporter—is Zales all the way. “I really enjoy the idea of jewelry as a fashion item, and how you stack and layer different pieces,” Drosos says, her voice revealing a slight Southern drawl. She runs her fingers across her set of three gold necklaces and explains that a Zales consultant gave her pointers on how to get the look she wanted—trendy, but still professional.

The Signet empire may not always be trendy, but it has considerably 1more momentum these days than it did when Drosos, the company’s first female CEO, took the helm. Not so long ago, it was not nearly as clear-cut what purpose each of Signet’s three biggest chains were most suitable for. Indeed, as Signet fell into a rut during the 2010s, its biggest banners cannibalized each other and started to become almost indistinguishable. Drosos recalls a time when any sales event at Zales would mean a corresponding drop in business at Kay, a problem made all the worse given that the chains often operated rival stores within yards of each other at the same tired malls. “We had all of our banners pretty much on top of each other in the middle tier,” says Drosos.

A clearer delineation between Signet’s top three brands, which together generate 77% of company sales, was just one item on the CEO’s long to-do list. Despite being the single largest jeweler in the country, Signet was dealing with a litany of major problems when Drosos took over. Zales, which Signet had acquired in 2014, turned out to be booby-trapped—a debt-laden retailer with too many terrible stores, losing favor with both customers and suppliers. Signet’s balance sheet was being dragged down by its store credit-card business; and it had all but ignored e-commerce. Overlaid on all that was the fallout from massive sexual discrimination and sexual harassment cases that culminated with the departure of Drosos’s predecessor.

So far, Drosos’s plan to reinvent Signet—a strategy shaped by her decades of experience at Procter & Gamble, as well as by a stint as CEO of a genetic-testing startup—has registered some big successes. Signet has shed hundreds of weak stores in the Kay and Zales chains and reduced its reliance on discounting. It sold off that credit-card business. And it has finally adapted to the e-commerce era, thanks to deals such as its recent acquisitions of retail site Blue Nile and the rental service Rocksbox. Drosos has also begun to change Signet’s culture—by making sure shell-shocked employees, primarily women, feel heard and included and are willing to buy into management’s vision, and by dramatically overhauling the board.

Signet sales hit $7.8 billion in 2021—up 22% from Drosos’s first year in the corner office, and up 50% from their pandemic lows—to reach a new record. In mid-December 2022, Signet reported better than expected sales and profits results for its third quarter, bolstering Drosos’s claims of success.

At the same time, there has been no shortage of reminders of Signet’s challenges. Sales have been hit by inflation as customers have pared back on jewelry, a discretionary category if ever there was one. Kay, Zales, and even Jared shoppers are not Tiffany shoppers, let alone Cartier, after all—they’re not the kinds of people likely to spend big on jewelry when times get tight. The mid- and lower tiers of the U.S. jewelry market are under enormous pressure, says Wendy Liebmann, CEO of WSL Strategic Retail: “We have come out of the pandemic and into inflation, where people are saying, ‘Do I really need it?’”

This holiday season could provide an early answer to that question: Signet typically gets 30% of annual sales in November and December. But whether jewelry shoppers show themselves to be skittish, bullish, or somewhere in between, there’s much work left to be done, all the more given that Wall Street is expecting hardly any sales growth in the next two years for Signet.

Drosos’s game plan will have to be about winning more market share by outdoing its rivals; further diversifying its businesses; and staying committed to e-commerce, lest it fall back into stagnation. “We were running an old playbook that had worked for the previous decade,” says Drosos. “We were much more about the merchandise, and working with vendors, than we were about listening to consumers.” The question is whether a new playbook and a new culture will keep Signet on an even keel in choppier waters.

The biggest jeweler, but with room to grow

Signet competes in a highly fragmented industry, where small regional chains and independent stores dominate. While it’s America’s biggest jeweler, it controls only 9.3% of a $76 billion market. It owes its size to 160 years of jewelry M&A.

The company’s portfolio dates back to the founding in 1862 of British jeweler H. Samuel. H. Samuel was absorbed in the 1980s by Ratner Jewelers, a conglomerate of U.K. and U.S. regional chains, that around the same time also absorbed Sterling Jewelers. Ratner changed its name to Signet in 1993. Today, Kay, a former anchor of the Sterling empire, generates 38% of Signet sales, while Zales accounts for 22%, and Jared 17%. Signet also owns Banter by Piercing Pagoda, the mall kiosk fixture where countless Americans had their earlobes punctured for the first time. Signet gets about 6% of sales in Britain and Ireland, 3% in Canada, and the rest in the States.

Signet’s size made it dominant for decades—but like many industry leaders, it became sclerotic. The 2014 acquisition of Zale Corp., at the time Signet’s main rival, looks in hindsight like a classic example of a company buying the growth that it couldn’t capture organically. The deal saddled Signet with more debt, along with a chain of stores that needed a big physical fix-up job, and had massive geographic and stylistic overlap with Kay. The strategic problem soon showed in the top line: Signet’s total sales peaked at $6.55 billion in the fiscal year ended in early 2016, then declined for the next five years, taking operating profitability down in the process.

That was the point at which Drosos stepped up. Drosos, a Signet director since 2012, had spent 25 years at P&G, rising to head of its beauty business. She had then detoured into biotech startup territory, becoming CEO at Assurex Health, a genetic testing company, and guiding it for four years until it got acquired. There, she says, she deepened her understanding of the power of data in decision-making—a knowledge that would prove pivotal in her new role.

Among the first obvious fixes on her plate was the need to cut stores in the Kay and Zales chains. Drosos ended up closing 1,250 stores across the company while opening 400 in better locations, with much of that change in the two biggest banners. All told, she closed 20% of Signet’s physical locations, which now number 2,500 stores in the U.S.

Drosos also turned to deeper customer research to guide her reforms. One of the things consumers were telling Signet but that management hadn’t really heard was that they were ready to shop online. Jewelry shopping was one of the last ramparts in retail to resist e-commerce, and it was an opportunity Signet had previously seemed to yawn at. (Tiffany was also late to e-commerce; LVMH, which bought Tiffany two years ago, has made turning the luxury jeweler into an e-commerce powerhouse a top priority.)

The new CEO realized that e-commerce wasn’t just about having a site that facilitates transactions, but about enabling people to conduct research before setting foot in stores. In one of her first moves as CEO, Drosos in 2017 bought JamesAllen.com—not because the site was a big business, but because it had tech that would upend the diamond industry. Its technology generates a 360-degree, high-definition image of every stone sold on the site, creating a virtual showroom in which buyers can choose from tens of thousands of diamonds. And that tech can now be used by the websites of Jared and Kay, too. “People can now see a diamond on our website better than they can see it in person, because we can blow it up and show it to them in HD,” boasts Drosos.

Tech has also been helpful in nerdy ways, specifically inventory management. If a ring is sitting unsold in a store in Fort Lauderdale, a salesperson in Minneapolis can access it for a customer. All this has meant a faster turnover of goods, meaning more fresh inventory in stores, and “newness” to draw in customers and protect profit margins.

Making e-commerce a priority turned out to be fortuitous, given the massive threat that would come from the COVID-19 pandemic. By mid-2020, Signet was dealing with the fallout of having stores closed for weeks on end in the spring—after all, Zales, Kay, and Jared were anything but essential retailers. Desperate to make sure revenue didn’t crater, the company sped the adoption of options like virtual selling and curbside pickup to accommodate shoppers wary of being in close quarters with others. Overall sales fell 15% in 2020, but the experience gave Signet some valuable new muscles. In 2017, some 5% of Signet’s sales were online; that rate now stands at 23%.

The James Allen deal also reflected a shift in Signet’s M&A strategy. The company had long been focused on buying out brick-and-mortar rivals; now, it’s more focused on deals that build up its e-commerce firepower, or at least win new customers. Central to this effort is Joan Hilson, a Victoria’s Secret alum who worked for Signet in the 1980s and whom Drosos hired in 2018 to be her strategy and finance chief.

One of Drosos and Hilson’s big goals was to fix Signet’s balance sheet, which was highly leveraged, and to bolster profitability by taking costs out of Signet’s operating structure. Since 2017, Signet has lowered its long-term debt by 80% to $147 million; and its operating profit margin was 11.6% in 2021, more than twice what it was just three years earlier. That stronger cash flow frees Signet to make bets through acquisitions. “It has generated liquidity for us to go out and grow our company,” says Hilson.

Take Blue Nile, which Drosos had been eyeing for years. Blue Nile created a sensation a decade ago as the first big online-only jewelry retailer. But the brand never truly took off, plateauing at $500 million a year in revenue. Signet bought it in September 2022 for $360 million, all cash, grabbing an e-commerce site with impressive virtual showrooms and an appealing young customer base. Other buys in 2022 include Rocksbox, a rental company; a small, specialized store chain called Diamonds Direct; and companies that help Signet offer services like maintenance and valuations.

The buying spree has made the Signet conglomerate even more sprawling: The company now has 11 retail banners under its umbrella, up from eight in 2017. That raises anew the question of whether Signet can keep the brands growing without confusing shoppers and competing against itself. “That’s an extraordinary accumulation of brands,” says Liebmann, the retail analyst. “There’s a lot of potential for fragmentation and cannibalizing your own business if you’re not careful.” But for now, the three big chains—Kay, Jared, and Zales—are growing simultaneously again, not least because Drosos’s team had the discipline to close the stores that needed to be closed.

Tackling a toxic culture

Drosos would not have been able to effect this turnaround without changing Signet’s culture. Like many retailers, Signet had long been a company with a mostly female workforce, a mostly female clientele, and mostly male leadership. By the time Drosos became CEO, that lineup had created an untenable situation.

The breaking point came after a devastating Washington Post story in February of 2017 that alleged years of systemic, rampant sexual harassment by male supervisors all the way up the chain of command. The story specifically implicated Mark Light, a Signet lifer who became CEO in 2014. Among other allegations, Light reportedly was seen in a pool with “nude and partially undressed female employees” at a corporate retreat. Light and Signet repeatedly denied the allegations. But Light left in the summer of 2017, citing unspecified health issues, and other implicated managers also departed. And in 2022, Signet settled a class action suit alleging gender bias in its hiring and compensation practices, shelling out $175 million to 68,000 current and former employees.

The toxic culture went beyond rampant misbehavior: It also took the form of a quasi-autocratic approach to business in which the bosses, disproportionately men, didn’t listen to what people in the field, the predominantly female frontline Signet workers, were seeing. Drosos, says that as a board member from 2012, she had always pushed for Signet to diversify its workforce and culture. When she became CEO, she says, the board told her to accelerate that effort.

Fixing a culture of fear and risk aversion is a tall order. “It was one of the things that made me the most nervous about taking this job,” Drosos says. Among her first moves: Making diversity and inclusion goals part of every leaders’ evaluation and creating a zero-tolerance policy for sexual harassment. “I’m going to create a clean slate. I’m not going to let history be our future,” she recalls thinking. Today, 42% of Signet employees at the vice-president level or higher are women; at the store level, 76% of assistant managers or higher are female. “Representation at that level sets a vision for all employees of what’s possible,” she said.

Another key fix: giving more autonomy and authority to store-level management. When she started as CEO, Drosos made the rounds of stores, sitting in on team meetings and even listening in on customer service calls to get a sense of what truly needed fixing. “What I realized very quickly was that it was quite a top-down culture of command and control,” she says. “We had brilliance in the organization that we just needed to unleash.” Store managers have a lot more say now in what Signet’s chains will carry. That move, combined with the closures of overlapping stores, has helped make individual stores far more productive: The average Signet store now generates 50% more in annual sales than it did pre-pandemic.

That coup reflects Drosos’s own history: She says she benefited from support from responsive higher-ups in her 25 years at Procter & Gamble. She counts among her mentors A.G. Lafley, the iconic CEO credited with leading a turnaround at the consumer giant in the early 2000s. It was at P&G that Drosos understood the importance of responding quickly to information from the front lines. She put those insights into action, and made her reputation, with her turnaround of famed skin-care brand Olay.

Armed with the in-depth market data for which P&G is famed, Drosos saw a big white space in the skin-care market between fancy, pricey department store brands, and low-price drugstore brands. Olay wasn’t selling a single product over $10 at Walmart or CVS. “There was a big gap,” she recalls. So she created a $25 moisturizer that she argued was on par with Crème de la Mer, a luxury beauty product sold at Neiman Marcus for hundreds of dollars a jar. The gambit took off: A brand that had seen $250 million in annual sales when she took it over had reached $2.5 billion a year by the time she was done with it. “It was really all about consumer understanding, and creating disruptions that would form a competitive advantage for us,” says Drosos.

A choppy economy ahead

For all of Signet’s recent success, the economy keeps reminding Drosos and her team how fragile that progress can be. In its most recent quarter, Signet’s comparable sales, or business excluding newly added or removed stores and business units, fell by 7.6%. Much of that drop was just the law of arithmetic after the dramatic sales bounce-back a year ago as the pandemic eased. Nonetheless, Wall Street is expecting very limited sales growth over the next three years, with analysts predicting that annual sales will hover at about $8 billion during that time.

To power through a softening economy, the company will have to keep following Drosos’s playbook of listening closely to what customers want. It has recently taken Jared further upscale with higher price points, and focused Kay more tightly on bridal jewelry and Zales on fashion, and analysts say moves like that could help protect its market share and margins. “Signet deserves credit for pivoting its assortment, services, and marketing to better cater to consumers,” says Neil Saunders, managing director of GlobalData.

Drosos recently got to try out Signet’s bridal-ring services, working with staff at James Allen to design her own engagement ring ahead of her marriage in 2021. The ring had an Italian Art Deco design from the 1930s. “They couldn’t find a diamond that they were proud enough of to put in the ring at first, and so they made me wait,” she recalls. The wait was well worth it, she says: “I’m a bit more of a bold statement maker myself.”