Z 世代是每个人都想弄清楚的谜。他们什么都想要:目标!工作与生活的平衡!灵活性!如果他们不能得到这些,他们可能会选择离开。

如果这种说法听起来有点老套,那就可能是因为你第一次听到它是在15年前千禧一代进入职场的时候。他们也什么都想要,但却面临批评,因为他们换了一份又一份工作,以追求他们热爱却仍然可以给他们带来喘息空间的职业。

那么,这些职场优先事项实际上是代际转变,还是仅仅是年轻员工在第一份工作中典型的心血来潮?这个问题引发了关于代际合法性的古老争论。长期以来,研究人员、人口统计学家和经济学家一直使用群组标签来分析历史和各种观点。但许多人认为,除了在我们的想象中,世代实际上并不存在,十年前的研究甚至发现,职场态度中并没有多少有意义的代际差异。

“[世代]不是自然规律,它们只是我们理解事物的方式。”克拉克大学(Clark University)的心理学家及高级研究学者杰弗里·阿内特说。“它们在某些方面是有用的。但重要的是不要认为它们是固定不变的。”

毕竟,用粗线条来大笔描绘一个群体的画像能够对个体进行分类。但我们也不应该对Z世代的行为不屑一顾,认为这是年轻人的愚蠢行为。这个问题很微妙。

阿内特的研究,以及职场专家的见解和数十年的研究给出了答案:Z世代的工作态度是代际身份和人生阶段的结果。是的,新冠疫情加速了过去几代人累积的愿望,并鼓励Z世代大胆说出这些愿望。尽管如此,这些20多岁的理想主义者眼中还有星星,但经济危机也让他们黯然失色。千禧一代以前就走过这条路。有些人甚至认为,这种职场理想主义始于30年前的X世代。

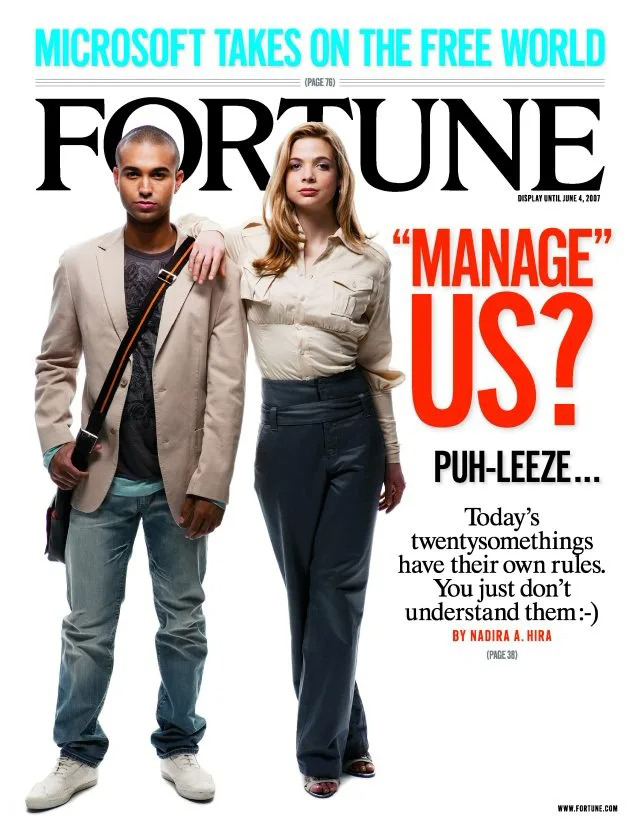

2007年7月《财富》杂志的一篇封面文章探讨了老板们在管理20多岁的年轻人时所面临的挑战。

将激情和灵活性理想化是20多岁年轻人的人生阶段的一部分,不分年代

今天理想主义的工作观源于经济在20世纪60年代开始从制造业转向信息服务和技术,由于自动化的兴起和几次经济衰退,这种理想主义的工作观在接下来的几十年里持续存在。

这造就了一种文化愿望,即寻找一份令人愉快的工作,而不仅仅是一份可以获得薪水的工作。阿内特说:“在那种经济环境下,你更有可能找到真正有趣的工作。”

阿内特在20世纪90年代开始研究年轻人,即在互联网泡沫时期开始职业生涯的X世代。他发现,许多人渴望基于身份的工作:一份不仅仅是一般意义上的工作,而是他们醒来后期待的工作。这与他们看待爱情的方式类似,他们将灵魂伴侣理想化,而不仅仅是寻找婚姻伴侣。他说,这是他们父母看待工作和爱情的代际转变,但他认为这一转变将成为未来几代18至25岁年轻人的常态——他后来将这一人生阶段定义为初成年期。

他说:“这些变化今天仍然存在,我们的研究对象已经从X世代变成了千禧一代,又从千禧一代变成了Z世代。”

大量的研究着重指出了20多岁的年轻人对令人愉快的工作的重视程度——工作被定义为“意义”、“目标”或“激情”,这支持了阿内特的观点。正如Quartz所引用的,《夏洛特观察家报》(Charlotte Observer)1999年的一篇文章报道说,X世代渴望在工作中获得乐趣。LinkedIn在2017年的一项研究发现,千禧一代将这种渴望提升到了一个新的水平,他们往往更看重激情而不是薪酬。如今,Z世代是最有可能说自己希望实现兴趣和价值观与职业匹配的一代人。

研究还显示,另一个受年轻员工欢迎的优先事项也有类似的记录:灵活性和随之而来的工作与生活的平衡。《夏洛特观察家报》的同一篇文章还报道说,X世代希望弹性工作制。《Inc.》在2015年将千禧一代描述为“极度渴望”灵活性的一代。快进到21世纪20年代,Z世代正在以同样的需求引领潮流。

阿内特发现,随着年龄的增长,拥有一份自己热爱的工作的浪漫欲望也会逐渐减弱。即使在2017年,年龄最大的36岁千禧一代已经开始重视稳定而不是激情。“在20岁出头的时候,人们仍然有远大的梦想。”阿内特说。“人们有这些理想,但他们最终必须让自己适应更容易实现的现实。”

新冠疫情让Z世代的职场欲望更加强烈

由于每一代人通常比上一代人更激进,20多岁的年轻人梦想得到能够实现目标又有灵活性的工作,这一现象随着新一代的出现变得更加明显。Z世代尤其如此,他们中的许多人是在远程工作和“大辞职潮”(Great Resignation)时代进入职场的。

这就是为什么工作与生活的融合需求是人口结构巨变的一部分,Rikleen Institute for Strategic Leadership的所长、《你们养育了我们,现在与我们一起工作:千禧一代、职业成功和组建强大的工作团队》(You Raised Us, Now Work With Us: Millennials, Career Success, and Building Strong Workplace Teams)一书的作者劳伦·斯蒂勒·里克林说。她解释说,婴儿潮一代更专注于如何在缺乏指导和培训的职场中生存,但随着时间的推移,更多的工作场所支持年轻员工将他们的价值观带到办公室。

里克林对《财富》杂志表示:“这不仅意味着你可以实现弹性工作,养家糊口,还意味着你能够过上更完整的生活,并更好地考虑健康和福祉。”

但她说,围绕这些工作与生活变化的代际趋势线发生的速度还不够快,没有跟得上如今千禧一代和Z世代的要求,而Z世代在更积极主动地推动这些变化。

千禧一代和Z世代根据他们的经济经历以不同的方式来实现他们相似的愿望:在大萧条时期(Great Recession)毕业的千禧一代不太愿意提出要求,从而获得他们想要的东西,因为他们觉得有一份工作就很幸运了,而在新冠疫情时期毕业的Z世代能够提出自主要求。

Z世代专家、代际动力学中心(The Center for Generational Kinetics)的创始人杰森·多尔西表示,与过去几代人相比,Z世代在职业规划被打乱并经历失业后,更注重追求激情和工作与生活的平衡。

当Z世代从不愿满足他们要求的雇主处辞职时,他们找一份新工作不成问题。因此,他们以反资本主义和反工作而闻名,这似乎与阿内特关于20多岁年轻人基于身份的工作原则的理论不一致。但这里也存在着另一个代际转变:千禧一代通常将职业视为自己身份的核心,而Z世代则认为有意义的工作只是他们身份的一部分。

多尔西告诉《财富》杂志:“其他几代人认为自己的身份从早上9点开始,到下午5点结束,而Z世代往往觉得自己的身份始于工作之外。这就减轻了他们通过目前的工作来定义自己的压力。”

但无论人生处于什么阶段或是哪个时代出生,许多人都喜欢疫情给他们带来的工作与生活的平衡。即使在新冠疫情之前,婴儿潮一代也渴望更多的非结构化日程安排。阿内特认为,年长的员工会喜欢选择自己的日程安排,但这对他们来说通常是不可能的。

“新冠疫情真的让事情发生了翻天覆地的变化。”他说。“看看这些年轻员工能否维持这种局面,将是一件有趣的事情。”(财富中文网)

译者:中慧言-王芳

Z 世代是每个人都想弄清楚的谜。他们什么都想要:目标!工作与生活的平衡!灵活性!如果他们不能得到这些,他们可能会选择离开。

如果这种说法听起来有点老套,那就可能是因为你第一次听到它是在15年前千禧一代进入职场的时候。他们也什么都想要,但却面临批评,因为他们换了一份又一份工作,以追求他们热爱却仍然可以给他们带来喘息空间的职业。

那么,这些职场优先事项实际上是代际转变,还是仅仅是年轻员工在第一份工作中典型的心血来潮?这个问题引发了关于代际合法性的古老争论。长期以来,研究人员、人口统计学家和经济学家一直使用群组标签来分析历史和各种观点。但许多人认为,除了在我们的想象中,世代实际上并不存在,十年前的研究甚至发现,职场态度中并没有多少有意义的代际差异。

“[世代]不是自然规律,它们只是我们理解事物的方式。”克拉克大学(Clark University)的心理学家及高级研究学者杰弗里·阿内特说。“它们在某些方面是有用的。但重要的是不要认为它们是固定不变的。”

毕竟,用粗线条来大笔描绘一个群体的画像能够对个体进行分类。但我们也不应该对Z世代的行为不屑一顾,认为这是年轻人的愚蠢行为。这个问题很微妙。

阿内特的研究,以及职场专家的见解和数十年的研究给出了答案:Z世代的工作态度是代际身份和人生阶段的结果。是的,新冠疫情加速了过去几代人累积的愿望,并鼓励Z世代大胆说出这些愿望。尽管如此,这些20多岁的理想主义者眼中还有星星,但经济危机也让他们黯然失色。千禧一代以前就走过这条路。有些人甚至认为,这种职场理想主义始于30年前的X世代。

2007年7月《财富》杂志的一篇封面文章探讨了老板们在管理20多岁的年轻人时所面临的挑战。

将激情和灵活性理想化是20多岁年轻人的人生阶段的一部分,不分年代

今天理想主义的工作观源于经济在20世纪60年代开始从制造业转向信息服务和技术,由于自动化的兴起和几次经济衰退,这种理想主义的工作观在接下来的几十年里持续存在。

这造就了一种文化愿望,即寻找一份令人愉快的工作,而不仅仅是一份可以获得薪水的工作。阿内特说:“在那种经济环境下,你更有可能找到真正有趣的工作。”

阿内特在20世纪90年代开始研究年轻人,即在互联网泡沫时期开始职业生涯的X世代。他发现,许多人渴望基于身份的工作:一份不仅仅是一般意义上的工作,而是他们醒来后期待的工作。这与他们看待爱情的方式类似,他们将灵魂伴侣理想化,而不仅仅是寻找婚姻伴侣。他说,这是他们父母看待工作和爱情的代际转变,但他认为这一转变将成为未来几代18至25岁年轻人的常态——他后来将这一人生阶段定义为初成年期。

他说:“这些变化今天仍然存在,我们的研究对象已经从X世代变成了千禧一代,又从千禧一代变成了Z世代。”

大量的研究着重指出了20多岁的年轻人对令人愉快的工作的重视程度——工作被定义为“意义”、“目标”或“激情”,这支持了阿内特的观点。正如Quartz所引用的,《夏洛特观察家报》(Charlotte Observer)1999年的一篇文章报道说,X世代渴望在工作中获得乐趣。LinkedIn在2017年的一项研究发现,千禧一代将这种渴望提升到了一个新的水平,他们往往更看重激情而不是薪酬。如今,Z世代是最有可能说自己希望实现兴趣和价值观与职业匹配的一代人。

研究还显示,另一个受年轻员工欢迎的优先事项也有类似的记录:灵活性和随之而来的工作与生活的平衡。《夏洛特观察家报》的同一篇文章还报道说,X世代希望弹性工作制。《Inc.》在2015年将千禧一代描述为“极度渴望”灵活性的一代。快进到21世纪20年代,Z世代正在以同样的需求引领潮流。

阿内特发现,随着年龄的增长,拥有一份自己热爱的工作的浪漫欲望也会逐渐减弱。即使在2017年,年龄最大的36岁千禧一代已经开始重视稳定而不是激情。“在20岁出头的时候,人们仍然有远大的梦想。”阿内特说。“人们有这些理想,但他们最终必须让自己适应更容易实现的现实。”

新冠疫情让Z世代的职场欲望更加强烈

由于每一代人通常比上一代人更激进,20多岁的年轻人梦想得到能够实现目标又有灵活性的工作,这一现象随着新一代的出现变得更加明显。Z世代尤其如此,他们中的许多人是在远程工作和“大辞职潮”(Great Resignation)时代进入职场的。

这就是为什么工作与生活的融合需求是人口结构巨变的一部分,Rikleen Institute for Strategic Leadership的所长、《你们养育了我们,现在与我们一起工作:千禧一代、职业成功和组建强大的工作团队》(You Raised Us, Now Work With Us: Millennials, Career Success, and Building Strong Workplace Teams)一书的作者劳伦·斯蒂勒·里克林说。她解释说,婴儿潮一代更专注于如何在缺乏指导和培训的职场中生存,但随着时间的推移,更多的工作场所支持年轻员工将他们的价值观带到办公室。

里克林对《财富》杂志表示:“这不仅意味着你可以实现弹性工作,养家糊口,还意味着你能够过上更完整的生活,并更好地考虑健康和福祉。”

但她说,围绕这些工作与生活变化的代际趋势线发生的速度还不够快,没有跟得上如今千禧一代和Z世代的要求,而Z世代在更积极主动地推动这些变化。

千禧一代和Z世代根据他们的经济经历以不同的方式来实现他们相似的愿望:在大萧条时期(Great Recession)毕业的千禧一代不太愿意提出要求,从而获得他们想要的东西,因为他们觉得有一份工作就很幸运了,而在新冠疫情时期毕业的Z世代能够提出自主要求。

Z世代专家、代际动力学中心(The Center for Generational Kinetics)的创始人杰森·多尔西表示,与过去几代人相比,Z世代在职业规划被打乱并经历失业后,更注重追求激情和工作与生活的平衡。

当Z世代从不愿满足他们要求的雇主处辞职时,他们找一份新工作不成问题。因此,他们以反资本主义和反工作而闻名,这似乎与阿内特关于20多岁年轻人基于身份的工作原则的理论不一致。但这里也存在着另一个代际转变:千禧一代通常将职业视为自己身份的核心,而Z世代则认为有意义的工作只是他们身份的一部分。

多尔西告诉《财富》杂志:“其他几代人认为自己的身份从早上9点开始,到下午5点结束,而Z世代往往觉得自己的身份始于工作之外。这就减轻了他们通过目前的工作来定义自己的压力。”

但无论人生处于什么阶段或是哪个时代出生,许多人都喜欢疫情给他们带来的工作与生活的平衡。即使在新冠疫情之前,婴儿潮一代也渴望更多的非结构化日程安排。阿内特认为,年长的员工会喜欢选择自己的日程安排,但这对他们来说通常是不可能的。

“新冠疫情真的让事情发生了翻天覆地的变化。”他说。“看看这些年轻员工能否维持这种局面,将是一件有趣的事情。”(财富中文网)

译者:中慧言-王芳

Gen Z is a puzzle everyone’s trying to figure out at work. They want it all: Purpose! Work-life balance! Flexibility! And if they don’t get it, they’ll leave the door swinging on their way out.

If that narrative sounds a little tired, it’s likely because you first heard it when millennials entered the workforce 15 years ago. They wanted it all, too, facing criticism for jumping from one job to the next in pursuit of a career they loved that still gave them room to breathe.

So are these workplace priorities actually a generational shift, or merely the typical whims of young workers in their first jobs? The question brings up an age-old debate on the legitimacy of generations. Labels for cohorts have long been used by researchers, demographers, and economists to analyze history and perspectives. But many have argued that generations don’t actually exist except in our imaginations, and research from a decade ago has even found that there aren’t many meaningful generational distinctions in workplace attitudes.

“[Generations are] not natural laws, they're just ways we have of understanding things,” says Jeffrey Arnett, psychologist and senior research scholar at Clark University. “They can be useful in some ways. But it's important not to view them as fixed.”

After all, using broad strokes to paint a picture of a cohort can pigeonhole individuals. But we also shouldn't just shrug off Gen Z's behaviors as a folly of youth. The question is nuanced.

Arnett’s research, along with additional insights from workplace experts and decades of studies, point to the answer: Gen Z’s attitudes about work are the result of both generational identity and life stage. Yes, the pandemic accelerated desires past generations set into motion and emboldened Gen Z to speak up about them. But still, these are idealistic 20-somethings who have stars in their eyes, who are also eclipsed by economic crises. Millennials have trod this ground before. And some even argue that this workplace idealism began with Gen X 30 years ago.

Idealizing passion and flexibility is part of the 20-something life stage, regardless of generation

Today’s idealistic view of work has roots in an economy that began to shift from manufacturing industries to information services and technology in the 1960s, continuing through the next several decades thanks to the rise of automation and a few recessions.

It created a cultural aspiration to find enjoyable work that’s more than just a paycheck, Arnett says: “In that kind of economy, you have a better chance of finding some kind of work that will actually be fun.”

Arnett began studying young adults in the 1990s—Gen Xers beginning their careers during the dot-com bubble. He found that many craved identity-based work: A job that wasn’t just a job, but something they looked forward to when waking up. It was similar to how they viewed love, idealizing a soulmate rather than just a marriage partner. It was a generational shift from how their parents viewed work and love, he says, but one he thought would become the norm for 18- to 25-year-olds in future generations—a life stage he then defined as emerging adulthood.

“Those changes we still have with us today now that we've gone from Gen X to millennials and from millennials to Gen Z,” he says.

There's plenty of research emphasizing how much 20-somethings value enjoyable work—which has variously been defined as “meaning,” “purpose,” or “passion”— to back up Arnett. As cited by Quartz, a 1999 article from the Charlotte Observer reported that Gen X craved fun at work. Millennials took that desire to the next level, a 2017 LinkedIn study found, often picking passion over pay. Now, Gen Z is the generation most likely to say they want better career alignment in their interests and values.

Studies also show a similar track record for another popular young worker priority: flexibility and the work-life balance that comes with it. The same Charlotte Observer article also reported that Gen X wanted flexible schedules. Inc. described millennials as “hell-bent” on flexibility in 2015. Fast forward to the 2020s, and Gen Z is leading the pack with the same demands.

Arnett finds that the romanticized desire for having a job you’re passionate about wanes as we age. Even in 2017, millennials, the oldest of whom were 36, were already starting to value stability over passion. “In their early 20s, people still dream big,” Arnett says. “People have these ideals, but they eventually have to accommodate themselves to a more accessible reality.”

The pandemic has made these workplace desires stronger for Gen Z

Since each generation is typically more progressive than the last, the 20-something dreams of purposeful and flexible work have become even more pronounced with each new cohort. That’s especially so with Gen Z, many of whom entered the workforce during the era of remote work and The Great Resignation.

That’s why work-life integration demands are part of a demographic sea change, says Lauren Stiller Rikleen, president at Rikleen Institute for Strategic Leadership and author of You Raised Us, Now Work With Us: Millennials, Career Success, and Building Strong Workplace Teams. Boomers were more focused on surviving in a workforce that lacked guidance and training, she explains, but more workplace support over time has enabled young workers to take their values into the office.

“That means not only the ability to have flexibility around raising a family, but to live a more complete life and think about health and wellness,” Rikleen tells Fortune.

But the generational trendline around some of these work-life changes isn’t happening fast enough for where millennials and Gen Z are today, she says, and Gen Z is more proactive in getting these changes across the line.

Millennials and Gen Z approached their similar desires differently based on their economic experiences: Graduating into the Great Recession made millennials less inclined to ask for the things they wanted because they just felt lucky to have a job, whereas graduating into the pandemic empowered Gen Z to make autonomous demands.

Gen Z is placing higher priority on pursuing their passions and work-life balance than past generations did at their age after having their career plans upended and experiencing job loss, says Jason Dorsey, Gen Z expert and founder of The Center for Generational Kinetics.

When Gen Z doesn't work for an employer willing to meet their demands, they have no problem finding a new job. As a result, they have a reputation for being anti-capitalist and anti-work, which may seem at odds with Arnett’s theory of the 20-something’s identity-based work tenet. But herein lies another generational shift: While millennials often view their career as central to their identity, Gen Z feels meaningful work is just one part of who they are.

“Whereas other generations thought that their identity started at 9 a.m. and ended at 5 p.m., Gen Z often feels that their identity starts outside of work,” Dorsey tells Fortune. “That puts less pressure on them to define themselves through their current employment.”

But regardless of life stage or generation, many people have loved the taste of work-life balance the pandemic has given them. Even pre-COVID, Boomers yearned for more unstructured schedules. Arnett believes that older workers would love to choose their own schedules, but that it hasn’t often been possible for them.

“COVID has really shaken things up,” he says. “It'll be interesting to see if these younger workers are able to sustain that.”