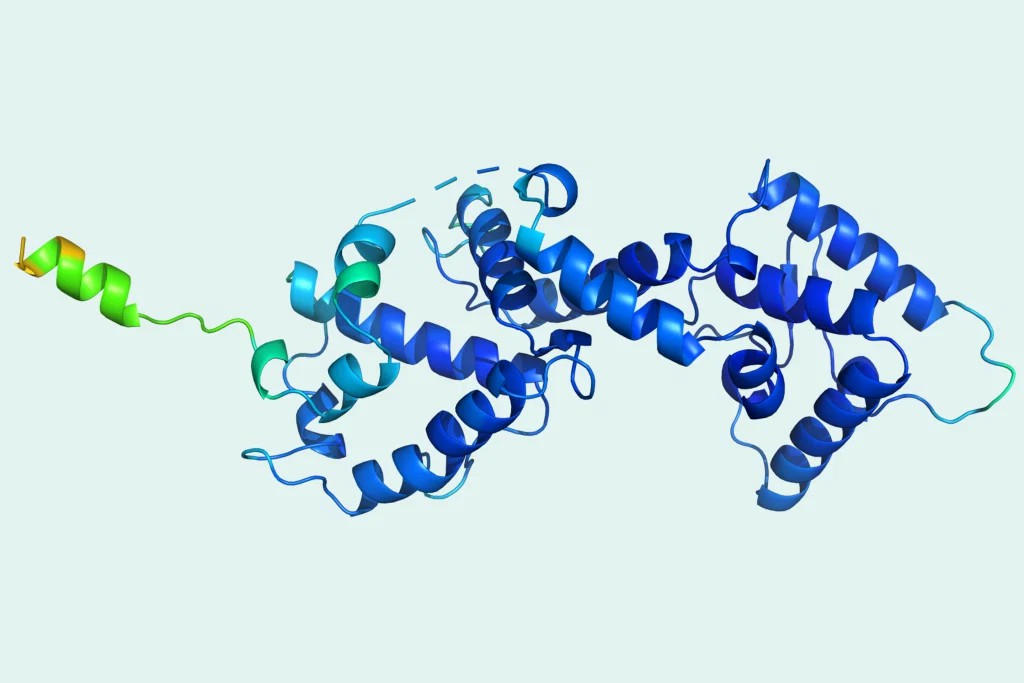

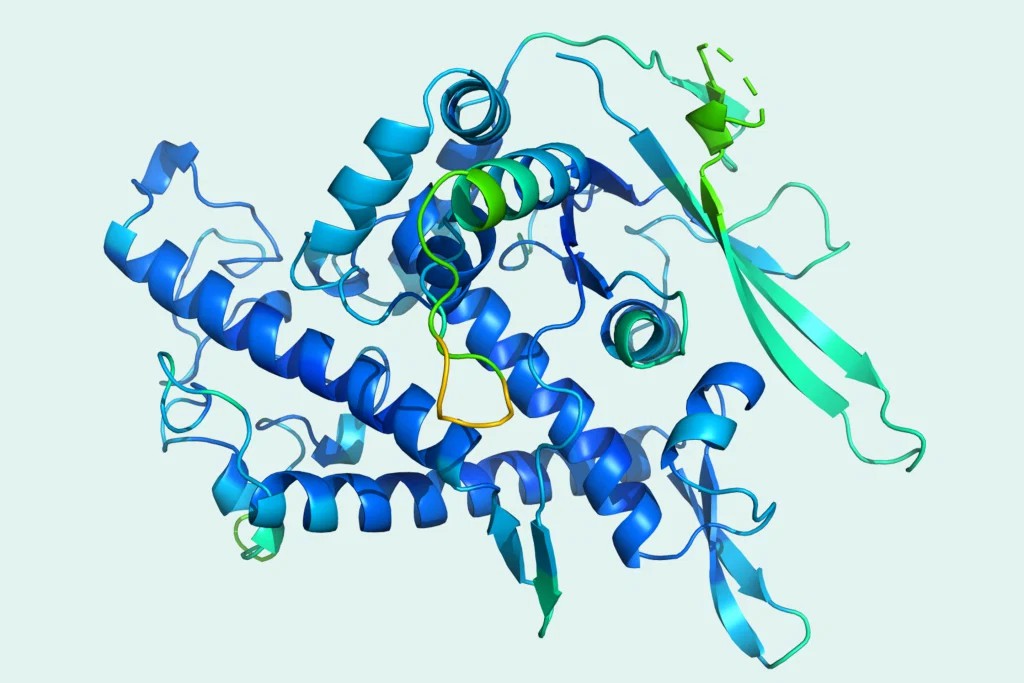

计算机生成与新冠病毒相关的蛋白质ORF8图像。图像由DeepMind开发的人工智能系统支持绘制。图片来源:COURTESY OF DEEPMIND

计算机生成与新冠病毒相关的蛋白质ORF8图像。图像由DeepMind开发的人工智能系统支持绘制。图片来源:COURTESY OF DEEPMIND2016年3月13日深夜,气温相当寒冷,两名男子头戴羊毛帽,身穿厚厚的外套,并肩走过韩国首尔市中心拥挤的街道。二人热烈地交谈,似乎完全忽视了周围饺子馆和烧烤店霓虹灯的诱惑。他们此行韩国肩负重任,多年的努力终于能够看到结果。最棒的是,他们刚刚成功了。

这次散步是为了庆祝。他们取得的成就将进一步巩固他们在计算机史上的地位。在古老的战略游戏围棋领域里,他们开发的人工智能软件已经充分掌握了个中奥秘,而且轻松击败了全球顶尖选手李世石。如今,两人开始讨论下一个目标,身后跟踪的纪录片摄制组捕捉到了当时的谈话。

“告诉你,我们可以解决蛋白质折叠问题。”德米斯•哈萨比斯对同伴大卫•西尔弗说。“那才是大成就。我相信现在能够去做了。以前我只是想过,现在肯定可以做成。”哈萨比斯是总部位于伦敦的人工智能公司DeepMind的联合创始人及首席执行官,正是该公司开发出了AlphaGo(阿尔法狗)。西尔弗则是DeepMind的计算机科学家,负责领导AlphaGo团队。

四年后,DeepMind实现了当年哈萨比斯在首尔散步时的设想。公司开发出了人工智能系统,能够根据基因序列来预测蛋白质的复杂形状,精确到单个原子宽度。靠着这项成就,DeepMind完成了需要近50年才能完成的科学探索。1972年,化学家克里斯蒂安•安芬森在诺贝尔奖获奖演说中提出,只有DNA才可以完全决定蛋白质的最终结构。这是惊人的猜想。当时连一个基因组都未完成测序。安芬森的理论开创了计算生物学的分支,目标是用复杂的数学模拟蛋白质结构,而不是实验。

DeepMind在围棋方面取得的成就确实很重要,但在围棋和计算机科学这两个相对偏僻的领域之外,几乎没有产生什么具体影响。解决蛋白质折叠问题则完全不同,对大多数人来说都有变革意义。蛋白质是生命的基本组成部分,也是大多数生物过程背后的运行机制。如果能够预测蛋白质的结构,将彻底改变人们对疾病的理解,还可以为癌症到老年痴呆症等各种疾病开发全新也更具针对性的药物。新药上市时间有望加快,药物研发成本减少数年时间,成本也节约数亿美元,还可能会拯救很多生命。

DeepMind首创的新方法在抗击SARS-CoV-2(也就是新冠病毒)的斗争中已经取得成果。以下是以游戏知名的公司如何揭开生物学最大秘密的故事。

形状莫测的积木

“蛋白质是细胞的主要机器。”加州大学伯克利分校的生物工程教授伊恩•霍姆斯表示。蛋白质的结构和形状对其工作方式至关重要,构成蛋白质分子晶格的小“口袋”是发生各种化学反应的地方。如果能够找到某种化学物质与其中一个口袋结合,这种物质就可以作为药物阻止或加速生物过程。生物工程师还能够创造出自然界中从未出现的全新蛋白质,而且具有独特的疗效。“如果我们可以利用蛋白质的力量,合理地设计用途,就能够制造出神奇的自我组装机器,发挥一些作用。”霍姆斯说。

但为了确保蛋白质达到想要的效果,把握其形状很重要。

蛋白质由氨基酸链组成,常被比作细绳上的珠子。至于珠子按照什么顺序穿起来,信息都存储在DNA里。但是,根据简单的基因指令很难预测完整的链条会形成多复杂的物理形状。氨基酸链根据分子间吸引和排斥的电化学规则折叠成某种结构。形状常常类似绳索和丝带缠绕而成的抽象雕塑:褶皱的带状物加上莫比乌斯带,就像卷曲环状的螺旋。20世纪60年代,物理学家和分子生物学家塞勒斯•列文塔尔发现,一种蛋白质的形状有太多可能性。如果想通过随机尝试组合找出蛋白质的准确结构,花的时间比已知宇宙的年龄还长。而且,几毫秒内蛋白质就会完成折叠。该观察被称为列文塔尔悖论。

到目前为止,只有通过所谓X射线晶体衍射才可以接近准确了解蛋白质的结构。顾名思义,首先需要将含有数百万蛋白质的溶液转化为晶体,本身就是很复杂的化学过程。然后,X射线发射到晶体上,科学家从获得的衍射图逆向工作,从而建立蛋白质图像。而且,还不是随便什么X射线都可以。要想获得很多蛋白质的结构,要由圆形的,大小堪比体育场的同步加速器发射X射线。

过程既昂贵又耗时。根据多伦多大学(University of Toronto)的研究人员估计,用X射线晶体衍射法测定单个蛋白质的结构需要约12个月,花费约12万美元。已知的蛋白质超过2亿种,每年大约能够发现3000万种,但其中只有不到20万种蛋白质通过X射线晶体衍射或其他实验方法绘制出了结构图。“人类的无知程度正在迅速增长。”计算物理学家约翰•乔普说,现在他担任DeepMind的高级研究员,负责领导蛋白质折叠团队。

过去50年里,自从克里斯蒂安•安芬森发表著名演讲以来,科学家们一直努力使用高性能计算机上运行的复杂数学模型加速分析蛋白质结构。“基本上就是尝试在计算机里创建蛋白质的数字双胞胎,然后尝试操作。”马里兰大学的细胞生物学和分子遗传学教授约翰•穆尔特说,他也是用数学算法通过DNA序列预测蛋白质结构的先驱。问题是,预测出的折叠模式经常有误,与科学家通过X射线晶体衍射发现的结构并不一致。事实上大约10年前,很少有模型预测大蛋白质形状时准确率可以超过三分之一。

蛋白质折叠模拟要占用庞大的算力。2000年,研究人员创建了名叫Fold@home的“公民科学”项目,人们能够捐出个人电脑和游戏机的闲置处理能力运行蛋白质折叠模拟。所有设备通过互联网连接在一起,从而打造全世界最强大的虚拟超级计算机之一。大家都希望帮研究人员摆脱列文塔尔悖论,通过随机实验和试错准确判断蛋白质的结构。目前该项目仍然在进行中,已经为超过225篇论文提供了数据,研究内容是与多种疾病相关的蛋白质。

尽管拥有强大的处理能力,Fold@home仍然深陷列文塔尔悖论,因为算法试图搜索所有可能的排列,从而找到蛋白质结构。破解蛋白质折叠的关键在于跳过艰苦搜索的过程,发现蛋白质DNA序列与结构联系的神秘模式,从而让计算机踏上全新捷径,直接从遗传学领域转到准确绘制形状。

严肃的游戏

德米斯•哈萨比斯对蛋白质折叠的兴趣始于一场游戏,他对很多事都是这样。哈萨比斯曾经是国际象棋天才,13岁时已经成为大师,一度在同年龄里排名世界第二。他对象棋的热爱后来转向对两件事感兴趣:一是游戏设计,二是研究自身意识的内在机制。他高中时开始为电子游戏公司工作,在剑桥大学(University of Cambridge)学习计算机科学后,1998年创立了电脑游戏初创公司Elixir Studios。

尽管曾经研发出两款获奖游戏,最终Elixir还是卖掉知识产权并关闭公司,哈萨比斯从伦敦大学学院(University College London)获得了认知神经科学博士学位。彼时他已经开始踏上漫漫征途,后来2010年联合创立了DeepMind。他开始研发通用人工智能软件,不仅可以学习执行很多任务,有些甚至比人类完成得更好。哈萨比斯曾经说过,DeepMind的远大目标是“解决智能问题,然后解决所有其他问题。”哈萨比斯也曾经暗示,蛋白质折叠可能就是“其他问题”里的第一批。

2009年,哈萨比斯在麻省理工学院(Massachusetts Institute of Technology)攻读博士后时,听说了一款名为Foldit的在线游戏。Foldit是由华盛顿大学(University of Washington)的研究人员设计,跟Fold@home类似,也是有关蛋白质折叠的“公民科学”项目。但Foldit并不是整合闲置的微芯片,而是利用闲置的大脑。

Foldit是类似益智游戏的游戏,并不掌握生物学领域知识的人类玩家比赛折叠蛋白质,如果能够得到合理的形状就可以获得积分。然后,研究人员分析得分最高的设计,看是否有助于破解蛋白质结构问题。游戏已经吸引成千上万玩家,并且一些记录案例中得到的蛋白质结构比研究蛋白质折叠的计算机算法更准确。“从这个角度来看,我觉得游戏很有趣,想着能不能利用游戏的上瘾性和游戏的乐趣,不仅让人们玩得开心,也做一些对科学有用的事情。”哈萨比斯说。

Foldit能够抓住哈萨比斯的想象力还有另一个原因。其实游戏是一种强化学习行为,特别适合训练人工智能。软件可以通过试验和试错从经验中学习,从而更好地完成任务。在游戏里软件能够无休止地试验,反复地玩,逐步改进,不对现实世界造成伤害的情况下提升技能水平,直到超过人类。游戏也有现成的方法判断某个特定的动作或某组动作是否有效,即积分和胜利。种种指标可以提供非常明确的标准衡量表现,在现实世界很多问题里则无法如此处理。现实世界遇到问题时,最有效的方法可能比较模糊,“获胜”的概念也可能不适用。

DeepMind的基础主要是将强化学习与称为深度学习的人工智能相结合。深度学习是基于神经网络的人工智能,所谓神经网络是大致基于人脑工作原理的软件。这种情况下,软件没有实际的神经细胞网络,而是一堆虚拟神经元分层排列,初始输入层接收数据,按照权重分配后传递到中间层,中间层依次执行相同操作,最终传递到输出层,输出层汇总各项加权值并算出结果。网络能够调整各项权重,直到产生理想的结果,例如准确识别猫的照片或国际象棋获胜。之所以被称为“深度学习”,并不是因为产生的结果一定深刻,当然也有可能深刻,但主要原因是网络由许多层构成,所以可以说具有深度。

DeepMind最初成功是用“深度强化学习”创建软件,自学玩经典的雅达利电脑游戏,如《乒乓球》(Pong)、《突围》(Breakout)和《太空入侵者》(Space Invaders)等,而且水平超过人类。正是这一成就让DeepMind受到谷歌(Google)等科技巨头的关注,据报道,2014年谷歌以4亿英镑(当时超过6亿美元)收购了DeepMind。之后公司主攻围棋并开发了AlphaGo系统,2016年击败了李世石。DeepMind接着开发了名叫AlphaZero的更通用系统版本,几乎能够学会所有两玩家回合制游戏,在这种游戏中,玩家都可以获得充分信息(没有机会隐藏信息,例如牌面朝下放置或隐藏位置)。去年,公司开发的系统还在高度复杂的即时战略游戏《星际争霸2》(Starcraft 2)中击败了顶尖的人类职业电竞玩家。

但哈萨比斯表示,一直认为公司在游戏方面的探索是完善人工智能系统的方式,之后能够应用于现实世界挑战,尤其是科学领域。“比赛只是训练场,但训练到底为了什么?最终是为了创造新知识。”他说。

DeepMind并非具有产品和客户的传统业务,本质上是推动人工智能前沿的研究实验室。公司的很多开发方法都已经公开,供所有人使用或借鉴。不过某些方面的进步对姊妹公司谷歌也颇有帮助。

DeepMind团队由工程师和科学家组成,帮助谷歌将尖端的人工智能技术融入产品。DeepMind的技术已经渗透各处,从谷歌地图(Google Maps)到数字助理,再到协助管理安卓手机电池电量的系统。谷歌为此向DeepMind支付费用,母公司Alphabet继续承担DeepMind带来的额外亏损。亏损规模并不小,2018年,公司亏损4.7亿英镑(当时约合5.1亿美元),这也是通过英国的商业注册机构公司登记局(Companies House)可以查到的最新一年公开记录。

不过如今员工超过1000人的DeepMind,还有一整个部门只负责人工智能的科学应用。该部门的负责人为39岁的印度人普什米•科里,他加入DeepMind之前曾经在微软从事人工智能研究。他表示,DeepMind的目标是解决“根节点”问题,这是数据科学家的惯用语,意思是希望解决能够解锁很多科学路径的基础问题。蛋白质折叠就是根节点之一,科里说。

“蛋白质折叠的奥运会”

1994年,当很多科学家刚开始使用复杂的计算机算法预测蛋白质折叠方式时,马里兰大学的生物学家墨尔特决定开办竞赛,用公正的方法评估哪种算法最好。他把比赛称为蛋白质结构预测关键评估(简称为CASP),之后每两年举办一次。

赛事具体如下,美国国立卫生研究院资助的蛋白质结构预测中心主办CASP,并说服从事X射线晶体衍射和其他实证研究的研究人员提供尚未公布的蛋白质结构,要求在CASP竞赛结束之前不公开相关结构。然后CASP将蛋白质DNA序列发给参赛者,参赛者用算法预测蛋白质结构。CASP判断预测与X射线晶体学家和实验学家发现的实际结构接近程度,然后根据算法对各种蛋白质预测的平均得分排名。“我称之为蛋白质折叠界的奥运会。”哈萨比斯说。2016年AlphaGo击败李世石后不久,DeepMind就打算赢得金牌。

DeepMind组建了小规模精干的团队,由六名机器学习研究人员和工程师组成。“让‘通才’入手是我们的理念。”哈萨比斯说。公司里并不缺乏人才。“前物理学家、前生物学家,大家都四处闲逛。”哈萨比斯有点啼笑皆非。“他们永远不知道之前的专业知识什么时候可以突然发挥作用。”最后团队成员增加到20人左右。

不过,DeepMind还是认为团队里至少要有一位真正的蛋白质折叠专家,后来选中了约翰•乔普。35岁的乔普像个大男孩,瘦得皮包骨,一头蓬乱斜梳的棕色头发,有点像20世纪90年代末高中车库乐队的低音吉他手。他在剑桥大学获得理论凝聚态物理硕士学位,之后在纽约由对冲基金亿万富翁大卫•肖创立的独立研究实验室D.E.Shaw Research工作。实验室专门研究计算生物学,包括蛋白质模拟。后来乔普在芝加哥大学获得了计算生物物理学博士学位,导师为卡尔•弗里德和托宾•索斯尼克,两位科学家皆因推动蛋白质折叠模型进步出名。“我曾经听说DeepMind对解决蛋白质结构有兴趣。”他说。于是他申请并顺利加入。

哈萨比斯和DeepMind团队的第一直觉是,蛋白质折叠能够用与围棋完全相同的方式解决,即深度强化学习。事实证明存在问题。首先,蛋白质折叠结构的可能性比围棋的步数还要多。更重要的是,DeepMind让工智能系统AlphaGo与自己对弈就可以掌握围棋的玩法。“所以可比性并不高,因为蛋白质折叠不是双人游戏。”哈萨比斯说,“有点违背自然。”

DeepMind很快发现,如果使用所谓监督式深度学习的人工智能培训方法,就能够更简便地取得进步。这是大多数商业应用里使用的人工智能,神经网络通过一组既定数据输入和相应输出,可以学习如何将给定的输入与给定输出相匹配。具体到蛋白质结构,DeepMind已经掌握约170000个蛋白质结构,能够作为训练数据。蛋白质数据库(PDB)是已知三维蛋白质形状及遗传序列的公共存储库,可以公开查询相关结构。

一些生物学家已经使用监督式深度学习预测蛋白质如何折叠。但此类人工智能系统表现最佳的正确率也只有50%,对生物学家或医学研究人员没有什么帮助,尤其是对结构未知的蛋白质,因为无法确定某次特定预测是否正确。

有种技术很有希望,其理念是基于蛋白质的进化史划分为不同的家族。各种家族里可能在一个DNA序列中找到相距遥远但似乎会同时突变的氨基酸对。此类所谓“共同进化”的现象很有帮助,因为共同进化的蛋白质很可能在蛋白质折叠结构中有联系。位于芝加哥的丰田技术研究所(Toyota Technological Institute)的科学家徐金波(音译)率先利用深入学习共同进化数据预测氨基酸联系。这种方法有点像是在连接点游戏里寻找点。科学家仍然要用其他软件找出点之间的线,过程中经常出错。有时候连点都找不准。

在2018年的CASP竞赛中,DeepMind应用了共同进化和预测联系的基本思想,但增加了两个重要的转折点。首先,系统没有试图确定两个氨基酸是否有联系,也就是二进制输出(即两个氨基酸可能有联系,也可能没有联系),而是决定让算法预测蛋白质里所有氨基酸对之间的距离。

在多数分子生物学家看来,这种方法似乎违反直觉,不过值得称赞的是,徐金波也独立提出了类似方法。毕竟,联系才是最重要的。对于DeepMind的深度学习专家来说,很明显距离是让神经网络发挥作用更好的指标,科里表示。“这只是深度学习的基础部分,如果与决策相关存在不确定性,最好是让神经网络整合不确定性,并决定如何应对。”他说。与联系不一样,距离包含了神经网络可调整和使用的丰富信息。

DeepMind另一项让人意外之处是引入第二个神经网络,用于预测氨基酸对之间的角度。有了距离和角度两个因素,DeepMind的算法就能够算出蛋白质结构的大致轮廓。然后,系统使用另一种非人工智能算法改进结构。DeepMind将相关组件整合到名为AlphaFold的系统中,横扫了2018年CASP(又称为第13届CASP,因为是两年一度比赛举办第13次。)比赛里结构最复杂的43种蛋白质中,AlphaFold在25种蛋白质中得分最高。第二名仅在三种蛋白质里得到高分。研究结果震惊了全行业。如果说之前还有人怀疑深度学习究竟是不是解决蛋白质折叠问题最有希望的方法,AlphaFold让所有人再无疑问。

回到白板

尽管如此,DeepMind还远没有达到哈萨比斯的目标,即完全解决蛋白质折叠问题。AlphaFold准确率只有一半,第13届CASP的104个蛋白质中,准确度可以达到X射线晶体衍射水平的只有三个。“我们不只想在CASP竞赛中夺魁,而是想真正解决问题。我们想打造对生物学家很重要的系统。”乔普说。

2018年CASP的结果公布后不久,DeepMind就开始加倍努力。乔普负责扩大的团队。团队并未简单地在AlphaFold基础上改进,而是返回原点,集思广益寻找完全不同的想法,他们希望新创意能够帮软件将精确度提升到更接近X射线晶体衍射级别。

乔普表示,接下来是整个项目中最可怕也最令人沮丧的时期之一,因为什么办法都没有。“我们花了三个月,结果都达不到第13届CASP的水平,开始真正感觉到恐慌。”他说。不过当时研究人员的尝试出现了一些改进,没到6个月系统已经比最初的AlphaFold有了明显改进。之后两年里一直延续该模式,乔普说。先是三个月一无所获,接下来三个月快速发展,接着又是平台期。

哈萨比斯说,DeepMind以前的项目也出现过类似模式,包括围棋项目,还有复杂的即时战略游戏《星际争霸2》项目。他说,公司克服问题的管理策略就是交替采取两种不同的工作方式。第一种哈萨比斯称之为“攻击模式”,尽可能推动团队,追求当前系统可以达到的极致表现。然后,全力以赴努力的效果似乎耗尽时,他就开始转向所谓的“创新模式”。期间哈萨比斯不再对团队施加压力,容忍甚至期待出现暂时性的后退,从而为研究人员和工程师提供修补新想法和尝试新手段的空间。他说:“要鼓励人们提出尽可能多的疯狂想法,还要头脑风暴。”该模式通常能够推动性能出现新飞跃,让团队切换回攻击模式。

生日大礼

2019年11月21日,DeepMind蛋白质折叠团队的研究员凯萨伦•图雅苏那科年满30岁。这一天也会因为另一个原因值得纪念。图雅苏那科拥有牛津大学(University of Oxford)计算生物学博士学位,在团队里负责为蛋白质折叠人工智能开发新测试集,新款人工智能叫AlphaFold 2,是DeepMind为2020年的CASP竞赛新开发的系统。那天早上她打开办公电脑时,收到系统对一批大约50个蛋白质序列预测的评估,所有序列均为最近才添加到蛋白质数据库中。她愣了一下,然后大吃一惊。AlphaFold 2确实一直在改进,但对该组蛋白质的预测结果惊人地准确。系统对好几个蛋白质结构结构预测误差在1.5埃以内,埃的距离单位相当于十分之一纳米,或大约一个原子的宽度。

自称“团队悲观主义者”的图雅苏那科说,第一反应并不是高兴而是有点想吐。“我当时很害怕。”她说。结果实在太好,她以为是自己犯了错,可能准备测试集时无意中把人工智能在训练数据里见过的几个蛋白质加了进来。如此一来AlphaFold 2基本上就可以作弊,轻易预测出准确的结构。图雅苏那科回忆说,当时坐在DeepMind自助餐厅俯瞰伦敦的圣潘克拉斯车站(St. Pancras Station),一杯接一杯地喝茶努力平复心情。随后,她和其他团队成员花了一整天,直到深夜才下班,之后几天也是如此,他们坐在工作站旁埋头梳理AlphaFold 2的训练数据,希望找出错误所在。

然而一个错误也没有。事实是,新系统在预测表现方面实现了巨大飞跃。AlphaFold 2与之前版本完全不同。人工智能不再只是各成分组合,一个用来预测氨基酸之间的距离,另一个预测角度,然后用第三个软件联系起来。现在的人工智能用单一的神经网络直接从DNA序列进行推理。虽然系统仍然接受进化信息,从而确定研究的蛋白质是否与以前见过的蛋白质有共同的祖先,并仔细检查目标蛋白质的DNA序列与其他已知序列之间的一致性,但不再需要哪些氨基酸对共同进化的明确数据。“我们并未提供更多信息,反而减少了信息。”乔普说。系统可以自由地得出见解,即祖先何时可能决定蛋白质的部分形状,以及何时可能彻底偏离。换句话说,系统根据经验培养出直觉,就像老练的人类科学家一样。

新系统的核心是“注意力”机制,顾名思义,注意力是让深度学习系统专注于某组输入,并对相关输入加大权重。举例来说,在识别猫的系统里,系统可能学会注意耳朵的形状,也会学习在鼻子附近寻找胡须。乔普比较了AlphaFold 2的功能与玩拼图游戏,过程中“能够将某些部分拼凑在一起而且非常确定,得到不同的本地解决方案,然后想办法将相关问题连接起来。”乔普说,神经网络的中层已经学会根据对DNA序列的分析推理几何和空间排列,以及氨基酸对如何连接。

DeepMind曾经在128个“张量处理核心”上训练AlphaFold 2,张量处理核心是在16块专门用于深度学习的计算机芯片上创建的数字运算大脑,芯片由谷歌设计并在数据中心使用,公司称连续运行了数周。(128个专用的人工智能核心大约相当于100到200块强大的图形处理芯片,可以在Xbox或PlayStation上呈现极其炫目的动画效果。)公司表示,经过训练的系统提取DNA序列后“几天内”就能够完成整个结构预测。

AlphaFold 2与前一代相比有个优势,就是提供可信程度,即系统对结构里每种氨基酸的预测都有信心分数。如果说AlphaFold 2可以切实帮到生物学家和医学研究人员,这项指标至关重要,因为研究者需要清楚何时能够合理依赖模型,以及何时需要更加谨慎。

尽管测试结果惊人,DeepMind仍然不能确定AlphaFold 2的预测效果。新冠病毒来袭时,公司才得到重要的线索。今年3月,AlphaFold 2可以预测出六种与SARS-CoV-2(引发疫情的病毒)相关但未被研究的蛋白质结构,后来科学家使用所谓低温电子显微镜的经验方法证实了其中一种。由此能够充分看出AlphaFold 2对现实世界的影响力。

惊人的结果

CASP比赛在5月到8月之间举行。蛋白质结构预测中心发布多批目标蛋白质,之后参赛方提交结构预测进行评估。今年比赛排名于11月30日公布。

每次预测均可以得到“全球距离测试总分”,简称GDT的指标评分,该指标实际上看预测结果与通过实证方法(如X射线晶体衍射或电子显微镜)得到的结构接近程度,单位为埃。CASP的主席穆尔特表示,满分是100分,如果得分能够达到90分或以上,说明与实证方法相当。根据CASP组织者判断的结构难度,蛋白质也会划分不同的组。

穆尔特看到AlphaFold 2的结果时简直不敢相信。他就像几个月前的图雅苏那科一样,刚开始的想法是出错了。也许比赛中一些蛋白质序列以前发表过?又或者DeepMind也许设法获得了未发布数据的缓存?

为了核实,他请位于德国图宾的根马克斯•普朗克发展生物学研究所(Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology)的蛋白质进化系主任安德烈•卢帕斯帮忙验证。卢帕斯让AlphaFold 2预测一个自己确信没有见过的结构,因为卢帕斯利用X射线结晶衍射从未成功观测到该蛋白质的关键部分。近十年来,卢帕斯一直因为该部分缺失而伤脑筋,但就是观测不到准确的形状。卢帕斯说,利用AlphaFold的预测后,他重新查看X射线数据。“没到半小时就得出了正确结构。”他说,“太令人吃惊了!”

2018年DeepMind在CASP中获得成功以来,诸多学术研究人员纷纷涌向深度学习技术。结果,该领域其他方面的表现都有所提高。在中等难度目标方面,其他竞争对手的平均最佳预测GDT得分为75,比两年前提高了10分。不过还是完全追不上AlphaFold 2,因为该系统预测蛋白质结构平均得分高达92,就算面对最复杂的蛋白质平均得分也有87。穆尔特表示AlphaFold 2的预测“与实证方法不相上下”,比如X射线晶体衍射。得出该结论后,11月30日星期一CASP发表了重大声明:50年前的蛋白质折叠问题已经解决。

诺贝尔奖获得者、英国最负盛名的科学机构皇家学会(The Royal Society)现任主席文基•拉马克里希南表示,AlphaFold 2在蛋白质折叠方面“取得了惊人的进步”。有AlphaFold 2相助,X射线晶体衍射和电子显微镜之类既昂贵又耗时的实证方法可能都会变成过去式。

蛋白质结构专家、曾任欧洲分子生物学实验室欧洲生物信息学研究所(European Molecular Biology Laboratory’s European Bioinformatics Institute)主任的珍妮特•桑顿表示,DeepMind的突破可以帮助科学家绘制出整个人类“蛋白质组”,即人体内所有蛋白质。目前人体蛋白质中只有四分之一被用作药物靶点,如果能够掌握其余蛋白质结构,就可以为研发新疗法创造巨大的机会。她还表示,人工智能软件还能够推动蛋白质工程发展,从而推动可持续发展,帮科学家创造新作物品种,提升每英亩种植土地出产的营养价值,还可能研究出可以消化塑料的酶。

不过,当前的问题仍然是DeepMind如何应用AlphaFold 2。哈萨比斯表示,公司将努力确保软件“最大程度发挥积极的社会影响”,他也承认公司尚未决定如何实现,只说明年某个时候将宣布。哈萨比斯还告诉《财富》杂志,DeepMind正在考虑如何围绕系统开发商业产品或建立合作伙伴关系。“系统对药物研发以及制药巨头作用都非常大。”不过他表示,商业产品的具体形式也尚未决定。

对于DeepMind来说,如果尝试商业化就意味着踏上新征程,而此前出售给Alphabet后公司还从来没有担心过收入。公司简单成立了名叫DeepMind Health的部门,正在与英国国家医疗服务体系(U.K.’s National Health Service)合作开发应用程序,该应用程序能够识别出存在患急性肾损伤风险的医院患者。但新闻报道称DeepMind的医院合作伙伴违反英国的数据保护法向其提供数百万患者的医疗记录后,合作陷入了争论。2019年,DeepMind Health正式并入新的谷歌健康部门。当时DeepMind表示,剥离健康业务可以专注自身的研究基础,而不必分心在谷歌已然很擅长的领域(如数据安全和客户支持)成立商业部门。

当然了,即便DeepMind要推出商业产品,也不会是第一家尝试商业化的人工智能研究公司。总部位于旧金山的OpenAI可能是最接近DeepMind的竞争对手,如今越发商业化。去年,OpenAI发布的第一个商业产品,企业能够使用人工智能界面将简短的手写提示组成连贯的长文本。该人工智能被称为GPT,商业价值尚未得到证实,而DeepMind的AlphaFold 2可能对制药公司或生物技术初创企业产生根本性的影响。在反垄断监管者调查Alphabet之际,拥有商业上可行的产品可能是很好的保险,以防将来拆分Googleplex时DeepMind失去财大气粗的母公司无条件支持。

有一点可以肯定,DeepMind在蛋白质折叠领域的探索并未结束。CASP竞争只是围绕预测单个蛋白质的结构。在生物学和医学领域,研究人员真正关心的通常是蛋白质如何相互作用。一种蛋白质是如何与另一种蛋白质或与某种特定的小分子结合?酶如何分解蛋白质?莫尔特说,预测相互作用和结合很可能成为未来CASP竞争的主要关注点。乔普表示,下一步DeepMind打算应对相关挑战。

而在蛋白质折叠以外的领域,AlphaFold 2的成功肯定也会发挥影响,将鼓励其他人在重大科学问题中应用深入学习。比如发现新的亚原子粒子,探索暗物质的奥秘,掌握核聚变或创造室温超导体。科里表示,在天体物理学方面,DeepMind已经发挥了积极的作用。Facebook的人工智能研究人员刚刚启动了深度学习项目,希望寻找新的化学催化剂。蛋白质折叠是基础科学当中第一个由人工智能解决的谜团,但肯定不会是最后一个。(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

2016年3月13日深夜,气温相当寒冷,两名男子头戴羊毛帽,身穿厚厚的外套,并肩走过韩国首尔市中心拥挤的街道。二人热烈地交谈,似乎完全忽视了周围饺子馆和烧烤店霓虹灯的诱惑。他们此行韩国肩负重任,多年的努力终于能够看到结果。最棒的是,他们刚刚成功了。

这次散步是为了庆祝。他们取得的成就将进一步巩固他们在计算机史上的地位。在古老的战略游戏围棋领域里,他们开发的人工智能软件已经充分掌握了个中奥秘,而且轻松击败了全球顶尖选手李世石。如今,两人开始讨论下一个目标,身后跟踪的纪录片摄制组捕捉到了当时的谈话。

“告诉你,我们可以解决蛋白质折叠问题。”德米斯•哈萨比斯对同伴大卫•西尔弗说。“那才是大成就。我相信现在能够去做了。以前我只是想过,现在肯定可以做成。”哈萨比斯是总部位于伦敦的人工智能公司DeepMind的联合创始人及首席执行官,正是该公司开发出了AlphaGo(阿尔法狗)。西尔弗则是DeepMind的计算机科学家,负责领导AlphaGo团队。

四年后,DeepMind实现了当年哈萨比斯在首尔散步时的设想。公司开发出了人工智能系统,能够根据基因序列来预测蛋白质的复杂形状,精确到单个原子宽度。靠着这项成就,DeepMind完成了需要近50年才能完成的科学探索。1972年,化学家克里斯蒂安•安芬森在诺贝尔奖获奖演说中提出,只有DNA才可以完全决定蛋白质的最终结构。这是惊人的猜想。当时连一个基因组都未完成测序。安芬森的理论开创了计算生物学的分支,目标是用复杂的数学模拟蛋白质结构,而不是实验。

DeepMind在围棋方面取得的成就确实很重要,但在围棋和计算机科学这两个相对偏僻的领域之外,几乎没有产生什么具体影响。解决蛋白质折叠问题则完全不同,对大多数人来说都有变革意义。蛋白质是生命的基本组成部分,也是大多数生物过程背后的运行机制。如果能够预测蛋白质的结构,将彻底改变人们对疾病的理解,还可以为癌症到老年痴呆症等各种疾病开发全新也更具针对性的药物。新药上市时间有望加快,药物研发成本减少数年时间,成本也节约数亿美元,还可能会拯救很多生命。

DeepMind首创的新方法在抗击SARS-CoV-2(也就是新冠病毒)的斗争中已经取得成果。以下是以游戏知名的公司如何揭开生物学最大秘密的故事。

形状莫测的积木

“蛋白质是细胞的主要机器。”加州大学伯克利分校的生物工程教授伊恩•霍姆斯表示。蛋白质的结构和形状对其工作方式至关重要,构成蛋白质分子晶格的小“口袋”是发生各种化学反应的地方。如果能够找到某种化学物质与其中一个口袋结合,这种物质就可以作为药物阻止或加速生物过程。生物工程师还能够创造出自然界中从未出现的全新蛋白质,而且具有独特的疗效。“如果我们可以利用蛋白质的力量,合理地设计用途,就能够制造出神奇的自我组装机器,发挥一些作用。”霍姆斯说。

但为了确保蛋白质达到想要的效果,把握其形状很重要。

蛋白质由氨基酸链组成,常被比作细绳上的珠子。至于珠子按照什么顺序穿起来,信息都存储在DNA里。但是,根据简单的基因指令很难预测完整的链条会形成多复杂的物理形状。氨基酸链根据分子间吸引和排斥的电化学规则折叠成某种结构。形状常常类似绳索和丝带缠绕而成的抽象雕塑:褶皱的带状物加上莫比乌斯带,就像卷曲环状的螺旋。20世纪60年代,物理学家和分子生物学家塞勒斯•列文塔尔发现,一种蛋白质的形状有太多可能性。如果想通过随机尝试组合找出蛋白质的准确结构,花的时间比已知宇宙的年龄还长。而且,几毫秒内蛋白质就会完成折叠。该观察被称为列文塔尔悖论。

到目前为止,只有通过所谓X射线晶体衍射才可以接近准确了解蛋白质的结构。顾名思义,首先需要将含有数百万蛋白质的溶液转化为晶体,本身就是很复杂的化学过程。然后,X射线发射到晶体上,科学家从获得的衍射图逆向工作,从而建立蛋白质图像。而且,还不是随便什么X射线都可以。要想获得很多蛋白质的结构,要由圆形的,大小堪比体育场的同步加速器发射X射线。

过程既昂贵又耗时。根据多伦多大学(University of Toronto)的研究人员估计,用X射线晶体衍射法测定单个蛋白质的结构需要约12个月,花费约12万美元。已知的蛋白质超过2亿种,每年大约能够发现3000万种,但其中只有不到20万种蛋白质通过X射线晶体衍射或其他实验方法绘制出了结构图。“人类的无知程度正在迅速增长。”计算物理学家约翰•乔普说,现在他担任DeepMind的高级研究员,负责领导蛋白质折叠团队。

过去50年里,自从克里斯蒂安•安芬森发表著名演讲以来,科学家们一直努力使用高性能计算机上运行的复杂数学模型加速分析蛋白质结构。“基本上就是尝试在计算机里创建蛋白质的数字双胞胎,然后尝试操作。”马里兰大学的细胞生物学和分子遗传学教授约翰•穆尔特说,他也是用数学算法通过DNA序列预测蛋白质结构的先驱。问题是,预测出的折叠模式经常有误,与科学家通过X射线晶体衍射发现的结构并不一致。事实上大约10年前,很少有模型预测大蛋白质形状时准确率可以超过三分之一。

蛋白质折叠模拟要占用庞大的算力。2000年,研究人员创建了名叫Fold@home的“公民科学”项目,人们能够捐出个人电脑和游戏机的闲置处理能力运行蛋白质折叠模拟。所有设备通过互联网连接在一起,从而打造全世界最强大的虚拟超级计算机之一。大家都希望帮研究人员摆脱列文塔尔悖论,通过随机实验和试错准确判断蛋白质的结构。目前该项目仍然在进行中,已经为超过225篇论文提供了数据,研究内容是与多种疾病相关的蛋白质。

尽管拥有强大的处理能力,Fold@home仍然深陷列文塔尔悖论,因为算法试图搜索所有可能的排列,从而找到蛋白质结构。破解蛋白质折叠的关键在于跳过艰苦搜索的过程,发现蛋白质DNA序列与结构联系的神秘模式,从而让计算机踏上全新捷径,直接从遗传学领域转到准确绘制形状。

严肃的游戏

德米斯•哈萨比斯对蛋白质折叠的兴趣始于一场游戏,他对很多事都是这样。哈萨比斯曾经是国际象棋天才,13岁时已经成为大师,一度在同年龄里排名世界第二。他对象棋的热爱后来转向对两件事感兴趣:一是游戏设计,二是研究自身意识的内在机制。他高中时开始为电子游戏公司工作,在剑桥大学(University of Cambridge)学习计算机科学后,1998年创立了电脑游戏初创公司Elixir Studios。

尽管曾经研发出两款获奖游戏,最终Elixir还是卖掉知识产权并关闭公司,哈萨比斯从伦敦大学学院(University College London)获得了认知神经科学博士学位。彼时他已经开始踏上漫漫征途,后来2010年联合创立了DeepMind。他开始研发通用人工智能软件,不仅可以学习执行很多任务,有些甚至比人类完成得更好。哈萨比斯曾经说过,DeepMind的远大目标是“解决智能问题,然后解决所有其他问题。”哈萨比斯也曾经暗示,蛋白质折叠可能就是“其他问题”里的第一批。

2009年,哈萨比斯在麻省理工学院(Massachusetts Institute of Technology)攻读博士后时,听说了一款名为Foldit的在线游戏。Foldit是由华盛顿大学(University of Washington)的研究人员设计,跟Fold@home类似,也是有关蛋白质折叠的“公民科学”项目。但Foldit并不是整合闲置的微芯片,而是利用闲置的大脑。

Foldit是类似益智游戏的游戏,并不掌握生物学领域知识的人类玩家比赛折叠蛋白质,如果能够得到合理的形状就可以获得积分。然后,研究人员分析得分最高的设计,看是否有助于破解蛋白质结构问题。游戏已经吸引成千上万玩家,并且一些记录案例中得到的蛋白质结构比研究蛋白质折叠的计算机算法更准确。“从这个角度来看,我觉得游戏很有趣,想着能不能利用游戏的上瘾性和游戏的乐趣,不仅让人们玩得开心,也做一些对科学有用的事情。”哈萨比斯说。

Foldit能够抓住哈萨比斯的想象力还有另一个原因。其实游戏是一种强化学习行为,特别适合训练人工智能。软件可以通过试验和试错从经验中学习,从而更好地完成任务。在游戏里软件能够无休止地试验,反复地玩,逐步改进,不对现实世界造成伤害的情况下提升技能水平,直到超过人类。游戏也有现成的方法判断某个特定的动作或某组动作是否有效,即积分和胜利。种种指标可以提供非常明确的标准衡量表现,在现实世界很多问题里则无法如此处理。现实世界遇到问题时,最有效的方法可能比较模糊,“获胜”的概念也可能不适用。

DeepMind的基础主要是将强化学习与称为深度学习的人工智能相结合。深度学习是基于神经网络的人工智能,所谓神经网络是大致基于人脑工作原理的软件。这种情况下,软件没有实际的神经细胞网络,而是一堆虚拟神经元分层排列,初始输入层接收数据,按照权重分配后传递到中间层,中间层依次执行相同操作,最终传递到输出层,输出层汇总各项加权值并算出结果。网络能够调整各项权重,直到产生理想的结果,例如准确识别猫的照片或国际象棋获胜。之所以被称为“深度学习”,并不是因为产生的结果一定深刻,当然也有可能深刻,但主要原因是网络由许多层构成,所以可以说具有深度。

DeepMind最初成功是用“深度强化学习”创建软件,自学玩经典的雅达利电脑游戏,如《乒乓球》(Pong)、《突围》(Breakout)和《太空入侵者》(Space Invaders)等,而且水平超过人类。正是这一成就让DeepMind受到谷歌(Google)等科技巨头的关注,据报道,2014年谷歌以4亿英镑(当时超过6亿美元)收购了DeepMind。之后公司主攻围棋并开发了AlphaGo系统,2016年击败了李世石。DeepMind接着开发了名叫AlphaZero的更通用系统版本,几乎能够学会所有两玩家回合制游戏,在这种游戏中,玩家都可以获得充分信息(没有机会隐藏信息,例如牌面朝下放置或隐藏位置)。去年,公司开发的系统还在高度复杂的即时战略游戏《星际争霸2》(Starcraft 2)中击败了顶尖的人类职业电竞玩家。

但哈萨比斯表示,一直认为公司在游戏方面的探索是完善人工智能系统的方式,之后能够应用于现实世界挑战,尤其是科学领域。“比赛只是训练场,但训练到底为了什么?最终是为了创造新知识。”他说。

DeepMind并非具有产品和客户的传统业务,本质上是推动人工智能前沿的研究实验室。公司的很多开发方法都已经公开,供所有人使用或借鉴。不过某些方面的进步对姊妹公司谷歌也颇有帮助。

DeepMind团队由工程师和科学家组成,帮助谷歌将尖端的人工智能技术融入产品。DeepMind的技术已经渗透各处,从谷歌地图(Google Maps)到数字助理,再到协助管理安卓手机电池电量的系统。谷歌为此向DeepMind支付费用,母公司Alphabet继续承担DeepMind带来的额外亏损。亏损规模并不小,2018年,公司亏损4.7亿英镑(当时约合5.1亿美元),这也是通过英国的商业注册机构公司登记局(Companies House)可以查到的最新一年公开记录。

不过如今员工超过1000人的DeepMind,还有一整个部门只负责人工智能的科学应用。该部门的负责人为39岁的印度人普什米•科里,他加入DeepMind之前曾经在微软从事人工智能研究。他表示,DeepMind的目标是解决“根节点”问题,这是数据科学家的惯用语,意思是希望解决能够解锁很多科学路径的基础问题。蛋白质折叠就是根节点之一,科里说。

“蛋白质折叠的奥运会”

1994年,当很多科学家刚开始使用复杂的计算机算法预测蛋白质折叠方式时,马里兰大学的生物学家墨尔特决定开办竞赛,用公正的方法评估哪种算法最好。他把比赛称为蛋白质结构预测关键评估(简称为CASP),之后每两年举办一次。

赛事具体如下,美国国立卫生研究院资助的蛋白质结构预测中心主办CASP,并说服从事X射线晶体衍射和其他实证研究的研究人员提供尚未公布的蛋白质结构,要求在CASP竞赛结束之前不公开相关结构。然后CASP将蛋白质DNA序列发给参赛者,参赛者用算法预测蛋白质结构。CASP判断预测与X射线晶体学家和实验学家发现的实际结构接近程度,然后根据算法对各种蛋白质预测的平均得分排名。“我称之为蛋白质折叠界的奥运会。”哈萨比斯说。2016年AlphaGo击败李世石后不久,DeepMind就打算赢得金牌。

DeepMind组建了小规模精干的团队,由六名机器学习研究人员和工程师组成。“让‘通才’入手是我们的理念。”哈萨比斯说。公司里并不缺乏人才。“前物理学家、前生物学家,大家都四处闲逛。”哈萨比斯有点啼笑皆非。“他们永远不知道之前的专业知识什么时候可以突然发挥作用。”最后团队成员增加到20人左右。

不过,DeepMind还是认为团队里至少要有一位真正的蛋白质折叠专家,后来选中了约翰•乔普。35岁的乔普像个大男孩,瘦得皮包骨,一头蓬乱斜梳的棕色头发,有点像20世纪90年代末高中车库乐队的低音吉他手。他在剑桥大学获得理论凝聚态物理硕士学位,之后在纽约由对冲基金亿万富翁大卫•肖创立的独立研究实验室D.E.Shaw Research工作。实验室专门研究计算生物学,包括蛋白质模拟。后来乔普在芝加哥大学获得了计算生物物理学博士学位,导师为卡尔•弗里德和托宾•索斯尼克,两位科学家皆因推动蛋白质折叠模型进步出名。“我曾经听说DeepMind对解决蛋白质结构有兴趣。”他说。于是他申请并顺利加入。

哈萨比斯和DeepMind团队的第一直觉是,蛋白质折叠能够用与围棋完全相同的方式解决,即深度强化学习。事实证明存在问题。首先,蛋白质折叠结构的可能性比围棋的步数还要多。更重要的是,DeepMind让工智能系统AlphaGo与自己对弈就可以掌握围棋的玩法。“所以可比性并不高,因为蛋白质折叠不是双人游戏。”哈萨比斯说,“有点违背自然。”

DeepMind很快发现,如果使用所谓监督式深度学习的人工智能培训方法,就能够更简便地取得进步。这是大多数商业应用里使用的人工智能,神经网络通过一组既定数据输入和相应输出,可以学习如何将给定的输入与给定输出相匹配。具体到蛋白质结构,DeepMind已经掌握约170000个蛋白质结构,能够作为训练数据。蛋白质数据库(PDB)是已知三维蛋白质形状及遗传序列的公共存储库,可以公开查询相关结构。

一些生物学家已经使用监督式深度学习预测蛋白质如何折叠。但此类人工智能系统表现最佳的正确率也只有50%,对生物学家或医学研究人员没有什么帮助,尤其是对结构未知的蛋白质,因为无法确定某次特定预测是否正确。

有种技术很有希望,其理念是基于蛋白质的进化史划分为不同的家族。各种家族里可能在一个DNA序列中找到相距遥远但似乎会同时突变的氨基酸对。此类所谓“共同进化”的现象很有帮助,因为共同进化的蛋白质很可能在蛋白质折叠结构中有联系。位于芝加哥的丰田技术研究所(Toyota Technological Institute)的科学家徐金波(音译)率先利用深入学习共同进化数据预测氨基酸联系。这种方法有点像是在连接点游戏里寻找点。科学家仍然要用其他软件找出点之间的线,过程中经常出错。有时候连点都找不准。

在2018年的CASP竞赛中,DeepMind应用了共同进化和预测联系的基本思想,但增加了两个重要的转折点。首先,系统没有试图确定两个氨基酸是否有联系,也就是二进制输出(即两个氨基酸可能有联系,也可能没有联系),而是决定让算法预测蛋白质里所有氨基酸对之间的距离。

在多数分子生物学家看来,这种方法似乎违反直觉,不过值得称赞的是,徐金波也独立提出了类似方法。毕竟,联系才是最重要的。对于DeepMind的深度学习专家来说,很明显距离是让神经网络发挥作用更好的指标,科里表示。“这只是深度学习的基础部分,如果与决策相关存在不确定性,最好是让神经网络整合不确定性,并决定如何应对。”他说。与联系不一样,距离包含了神经网络可调整和使用的丰富信息。

DeepMind另一项让人意外之处是引入第二个神经网络,用于预测氨基酸对之间的角度。有了距离和角度两个因素,DeepMind的算法就能够算出蛋白质结构的大致轮廓。然后,系统使用另一种非人工智能算法改进结构。DeepMind将相关组件整合到名为AlphaFold的系统中,横扫了2018年CASP(又称为第13届CASP,因为是两年一度比赛举办第13次。)比赛里结构最复杂的43种蛋白质中,AlphaFold在25种蛋白质中得分最高。第二名仅在三种蛋白质里得到高分。研究结果震惊了全行业。如果说之前还有人怀疑深度学习究竟是不是解决蛋白质折叠问题最有希望的方法,AlphaFold让所有人再无疑问。

回到白板

尽管如此,DeepMind还远没有达到哈萨比斯的目标,即完全解决蛋白质折叠问题。AlphaFold准确率只有一半,第13届CASP的104个蛋白质中,准确度可以达到X射线晶体衍射水平的只有三个。“我们不只想在CASP竞赛中夺魁,而是想真正解决问题。我们想打造对生物学家很重要的系统。”乔普说。

2018年CASP的结果公布后不久,DeepMind就开始加倍努力。乔普负责扩大的团队。团队并未简单地在AlphaFold基础上改进,而是返回原点,集思广益寻找完全不同的想法,他们希望新创意能够帮软件将精确度提升到更接近X射线晶体衍射级别。

乔普表示,接下来是整个项目中最可怕也最令人沮丧的时期之一,因为什么办法都没有。“我们花了三个月,结果都达不到第13届CASP的水平,开始真正感觉到恐慌。”他说。不过当时研究人员的尝试出现了一些改进,没到6个月系统已经比最初的AlphaFold有了明显改进。之后两年里一直延续该模式,乔普说。先是三个月一无所获,接下来三个月快速发展,接着又是平台期。

哈萨比斯说,DeepMind以前的项目也出现过类似模式,包括围棋项目,还有复杂的即时战略游戏《星际争霸2》项目。他说,公司克服问题的管理策略就是交替采取两种不同的工作方式。第一种哈萨比斯称之为“攻击模式”,尽可能推动团队,追求当前系统可以达到的极致表现。然后,全力以赴努力的效果似乎耗尽时,他就开始转向所谓的“创新模式”。期间哈萨比斯不再对团队施加压力,容忍甚至期待出现暂时性的后退,从而为研究人员和工程师提供修补新想法和尝试新手段的空间。他说:“要鼓励人们提出尽可能多的疯狂想法,还要头脑风暴。”该模式通常能够推动性能出现新飞跃,让团队切换回攻击模式。

生日大礼

2019年11月21日,DeepMind蛋白质折叠团队的研究员凯萨伦•图雅苏那科年满30岁。这一天也会因为另一个原因值得纪念。图雅苏那科拥有牛津大学(University of Oxford)计算生物学博士学位,在团队里负责为蛋白质折叠人工智能开发新测试集,新款人工智能叫AlphaFold 2,是DeepMind为2020年的CASP竞赛新开发的系统。那天早上她打开办公电脑时,收到系统对一批大约50个蛋白质序列预测的评估,所有序列均为最近才添加到蛋白质数据库中。她愣了一下,然后大吃一惊。AlphaFold 2确实一直在改进,但对该组蛋白质的预测结果惊人地准确。系统对好几个蛋白质结构结构预测误差在1.5埃以内,埃的距离单位相当于十分之一纳米,或大约一个原子的宽度。

自称“团队悲观主义者”的图雅苏那科说,第一反应并不是高兴而是有点想吐。“我当时很害怕。”她说。结果实在太好,她以为是自己犯了错,可能准备测试集时无意中把人工智能在训练数据里见过的几个蛋白质加了进来。如此一来AlphaFold 2基本上就可以作弊,轻易预测出准确的结构。图雅苏那科回忆说,当时坐在DeepMind自助餐厅俯瞰伦敦的圣潘克拉斯车站(St. Pancras Station),一杯接一杯地喝茶努力平复心情。随后,她和其他团队成员花了一整天,直到深夜才下班,之后几天也是如此,他们坐在工作站旁埋头梳理AlphaFold 2的训练数据,希望找出错误所在。

然而一个错误也没有。事实是,新系统在预测表现方面实现了巨大飞跃。AlphaFold 2与之前版本完全不同。人工智能不再只是各成分组合,一个用来预测氨基酸之间的距离,另一个预测角度,然后用第三个软件联系起来。现在的人工智能用单一的神经网络直接从DNA序列进行推理。虽然系统仍然接受进化信息,从而确定研究的蛋白质是否与以前见过的蛋白质有共同的祖先,并仔细检查目标蛋白质的DNA序列与其他已知序列之间的一致性,但不再需要哪些氨基酸对共同进化的明确数据。“我们并未提供更多信息,反而减少了信息。”乔普说。系统可以自由地得出见解,即祖先何时可能决定蛋白质的部分形状,以及何时可能彻底偏离。换句话说,系统根据经验培养出直觉,就像老练的人类科学家一样。

新系统的核心是“注意力”机制,顾名思义,注意力是让深度学习系统专注于某组输入,并对相关输入加大权重。举例来说,在识别猫的系统里,系统可能学会注意耳朵的形状,也会学习在鼻子附近寻找胡须。乔普比较了AlphaFold 2的功能与玩拼图游戏,过程中“能够将某些部分拼凑在一起而且非常确定,得到不同的本地解决方案,然后想办法将相关问题连接起来。”乔普说,神经网络的中层已经学会根据对DNA序列的分析推理几何和空间排列,以及氨基酸对如何连接。

DeepMind曾经在128个“张量处理核心”上训练AlphaFold 2,张量处理核心是在16块专门用于深度学习的计算机芯片上创建的数字运算大脑,芯片由谷歌设计并在数据中心使用,公司称连续运行了数周。(128个专用的人工智能核心大约相当于100到200块强大的图形处理芯片,可以在Xbox或PlayStation上呈现极其炫目的动画效果。)公司表示,经过训练的系统提取DNA序列后“几天内”就能够完成整个结构预测。

AlphaFold 2与前一代相比有个优势,就是提供可信程度,即系统对结构里每种氨基酸的预测都有信心分数。如果说AlphaFold 2可以切实帮到生物学家和医学研究人员,这项指标至关重要,因为研究者需要清楚何时能够合理依赖模型,以及何时需要更加谨慎。

尽管测试结果惊人,DeepMind仍然不能确定AlphaFold 2的预测效果。新冠病毒来袭时,公司才得到重要的线索。今年3月,AlphaFold 2可以预测出六种与SARS-CoV-2(引发疫情的病毒)相关但未被研究的蛋白质结构,后来科学家使用所谓低温电子显微镜的经验方法证实了其中一种。由此能够充分看出AlphaFold 2对现实世界的影响力。

惊人的结果

CASP比赛在5月到8月之间举行。蛋白质结构预测中心发布多批目标蛋白质,之后参赛方提交结构预测进行评估。今年比赛排名于11月30日公布。

每次预测均可以得到“全球距离测试总分”,简称GDT的指标评分,该指标实际上看预测结果与通过实证方法(如X射线晶体衍射或电子显微镜)得到的结构接近程度,单位为埃。CASP的主席穆尔特表示,满分是100分,如果得分能够达到90分或以上,说明与实证方法相当。根据CASP组织者判断的结构难度,蛋白质也会划分不同的组。

穆尔特看到AlphaFold 2的结果时简直不敢相信。他就像几个月前的图雅苏那科一样,刚开始的想法是出错了。也许比赛中一些蛋白质序列以前发表过?又或者DeepMind也许设法获得了未发布数据的缓存?

为了核实,他请位于德国图宾的根马克斯•普朗克发展生物学研究所(Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology)的蛋白质进化系主任安德烈•卢帕斯帮忙验证。卢帕斯让AlphaFold 2预测一个自己确信没有见过的结构,因为卢帕斯利用X射线结晶衍射从未成功观测到该蛋白质的关键部分。近十年来,卢帕斯一直因为该部分缺失而伤脑筋,但就是观测不到准确的形状。卢帕斯说,利用AlphaFold的预测后,他重新查看X射线数据。“没到半小时就得出了正确结构。”他说,“太令人吃惊了!”

2018年DeepMind在CASP中获得成功以来,诸多学术研究人员纷纷涌向深度学习技术。结果,该领域其他方面的表现都有所提高。在中等难度目标方面,其他竞争对手的平均最佳预测GDT得分为75,比两年前提高了10分。不过还是完全追不上AlphaFold 2,因为该系统预测蛋白质结构平均得分高达92,就算面对最复杂的蛋白质平均得分也有87。穆尔特表示AlphaFold 2的预测“与实证方法不相上下”,比如X射线晶体衍射。得出该结论后,11月30日星期一CASP发表了重大声明:50年前的蛋白质折叠问题已经解决。

诺贝尔奖获得者、英国最负盛名的科学机构皇家学会(The Royal Society)现任主席文基•拉马克里希南表示,AlphaFold 2在蛋白质折叠方面“取得了惊人的进步”。有AlphaFold 2相助,X射线晶体衍射和电子显微镜之类既昂贵又耗时的实证方法可能都会变成过去式。

蛋白质结构专家、曾任欧洲分子生物学实验室欧洲生物信息学研究所(European Molecular Biology Laboratory’s European Bioinformatics Institute)主任的珍妮特•桑顿表示,DeepMind的突破可以帮助科学家绘制出整个人类“蛋白质组”,即人体内所有蛋白质。目前人体蛋白质中只有四分之一被用作药物靶点,如果能够掌握其余蛋白质结构,就可以为研发新疗法创造巨大的机会。她还表示,人工智能软件还能够推动蛋白质工程发展,从而推动可持续发展,帮科学家创造新作物品种,提升每英亩种植土地出产的营养价值,还可能研究出可以消化塑料的酶。

不过,当前的问题仍然是DeepMind如何应用AlphaFold 2。哈萨比斯表示,公司将努力确保软件“最大程度发挥积极的社会影响”,他也承认公司尚未决定如何实现,只说明年某个时候将宣布。哈萨比斯还告诉《财富》杂志,DeepMind正在考虑如何围绕系统开发商业产品或建立合作伙伴关系。“系统对药物研发以及制药巨头作用都非常大。”不过他表示,商业产品的具体形式也尚未决定。

对于DeepMind来说,如果尝试商业化就意味着踏上新征程,而此前出售给Alphabet后公司还从来没有担心过收入。公司简单成立了名叫DeepMind Health的部门,正在与英国国家医疗服务体系(U.K.’s National Health Service)合作开发应用程序,该应用程序能够识别出存在患急性肾损伤风险的医院患者。但新闻报道称DeepMind的医院合作伙伴违反英国的数据保护法向其提供数百万患者的医疗记录后,合作陷入了争论。2019年,DeepMind Health正式并入新的谷歌健康部门。当时DeepMind表示,剥离健康业务可以专注自身的研究基础,而不必分心在谷歌已然很擅长的领域(如数据安全和客户支持)成立商业部门。

当然了,即便DeepMind要推出商业产品,也不会是第一家尝试商业化的人工智能研究公司。总部位于旧金山的OpenAI可能是最接近DeepMind的竞争对手,如今越发商业化。去年,OpenAI发布的第一个商业产品,企业能够使用人工智能界面将简短的手写提示组成连贯的长文本。该人工智能被称为GPT,商业价值尚未得到证实,而DeepMind的AlphaFold 2可能对制药公司或生物技术初创企业产生根本性的影响。在反垄断监管者调查Alphabet之际,拥有商业上可行的产品可能是很好的保险,以防将来拆分Googleplex时DeepMind失去财大气粗的母公司无条件支持。

有一点可以肯定,DeepMind在蛋白质折叠领域的探索并未结束。CASP竞争只是围绕预测单个蛋白质的结构。在生物学和医学领域,研究人员真正关心的通常是蛋白质如何相互作用。一种蛋白质是如何与另一种蛋白质或与某种特定的小分子结合?酶如何分解蛋白质?莫尔特说,预测相互作用和结合很可能成为未来CASP竞争的主要关注点。乔普表示,下一步DeepMind打算应对相关挑战。

而在蛋白质折叠以外的领域,AlphaFold 2的成功肯定也会发挥影响,将鼓励其他人在重大科学问题中应用深入学习。比如发现新的亚原子粒子,探索暗物质的奥秘,掌握核聚变或创造室温超导体。科里表示,在天体物理学方面,DeepMind已经发挥了积极的作用。Facebook的人工智能研究人员刚刚启动了深度学习项目,希望寻找新的化学催化剂。蛋白质折叠是基础科学当中第一个由人工智能解决的谜团,但肯定不会是最后一个。(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

It is March 13, 2016. Two men, dressed in winter coats and woolen hats to defend against the frigid night air, walk side by side through the crowded streets of downtown Seoul. Locked in animated conversation, they seem oblivious to the pulsating neon enticements of the surrounding dumpling houses and barbecue joints. They are visitors, having come to South Korea on a mission, the culmination of years of effort—and they have just succeeded.

This is a celebratory stroll. What they have achieved will cement their places in the annals of computer science: They have built a piece of artificial intelligence software able to play the ancient strategy game Go so expertly that it handily defeated the world’s top player, Lee Sedol. Now the two men are discussing their next goal, their conversation captured by a documentary film crew shadowing them.

“I’m telling you, we can solve protein folding,” Demis Hassabis says to his walking companion, David Silver. “That’s like, I mean, it’s just huge. I am sure we can do that now. I thought we could do that before, but now we definitely can do it.” Hassabis is the cofounder and chief executive officer of DeepMind, the London-based A.I. company that built AlphaGo. Silver is the DeepMind computer scientist who led the AlphaGo team.

Four years later, DeepMind has just accomplished what Hassabis broached in that nocturnal amble: It has created an A.I. system that can predict the complex shapes of proteins down to an atom’s-width accuracy from the genetic sequences that encode them. With this achievement, DeepMind has completed an almost 50-year-old scientific quest. In 1972, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, chemist Christian Anfinsen postulated that DNA alone should fully determine the final structure a protein takes. It was a remarkable conjecture. At the time, not a single genome had been sequenced yet. But Anfinsen’s theory launched an entire subfield of computational biology with the goal of using complex mathematics, instead of empirical experiments, to model proteins.

DeepMind’s achievement with Go was important—but it had little concrete impact outside the relatively cliquish worlds of Go and computer science. Solving protein folding is different: It could prove transformative for much of humanity. Proteins are the basic building blocks of life and the mechanism behind most biological processes. Being able to predict their structure could revolutionize our understanding of disease and lead to new, more targeted pharmaceuticals for disorders from cancer to Alzheimer’s disease. It will likely accelerate the time it takes to bring new medicines to market, potentially shaving years and hundreds of millions of dollars in costs from drug development, and potentially saving lives as a result.

The new method pioneered by DeepMind is already yielding results in the fight against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. What follows is the story of how a company best known for playing games came to unlock one of biology’s greatest secrets.

Building blocks with elusive shapes

“Proteins are the main machines of the cell,” Ian Holmes, a professor of bioengineering at the University of California at Berkeley, says. “And the structure and shape of them is crucial to how they operate.” Small “pockets” within the lattice of molecules that make up the protein are where various chemical reactions take place. If you can find a chemical that will bind to one of these pockets, then that substance can be used as a drug—to either disable or accelerate a biological process. Bioengineers can also create entirely new proteins never before seen in nature with unique therapeutic properties. “If we could tap into the power of proteins and rationally engineer them to any purpose, then we could build these remarkable self-assembling machines that could do things for us,” Holmes says.

But to be sure the protein will do what you want, it’s important to know its shape.

Proteins consist of chains of amino acids, often compared to beads on a string. The recipe for which beads to string in what order is encoded in DNA. But the complex physical shape the completed chain will take is extremely difficult to predict from those simple genetic instructions. Amino acid chains collapse—or fold—into a structure based on electrochemical rules of attraction and repulsion between molecules. The resulting shapes frequently resemble abstract sculptures formed from tangles of cord and ribbon: pleated banderoles joined to Möbius strip–like curlicues and looping helixes. In the 1960s, Cyrus Levinthal, a physicist and molecular biologist, determined that there were so many plausible shapes a protein might assume that it would take longer than the known age of the universe to arrive at the correct structure by randomly trying combinations—and yet, the protein folds itself in milliseconds. This observation has become known as Levinthal’s Paradox.

Until now, the only way to know a protein’s structure with near certainty was through a method known as X-ray crystallography. As the name implies, this involves turning solutions of millions of proteins into crystals, a chemical process that is itself tricky. X-rays are then fired at these crystals, allowing a scientist to work backward from the diffraction patterns they make to build up a picture of the protein itself. Oh, and not just any X-rays: For many proteins, the X-rays need to be produced by a massive, stadium-size circular particle accelerator called a synchrotron.

The process is expensive and time-consuming: It takes about 12 months and approximately $120,000 to determine a single protein’s structure with X-ray crystallography, according to one estimate from researchers at the University of Toronto. There are over 200 million known proteins, with about 30 million more being discovered every year, and yet fewer than 200,000 of these have had their structures mapped with X-ray crystallography or other experimental methods. “Our level of ignorance is growing rapidly,” says John Jumper, a computational physicist who is now a senior researcher at DeepMind and leads its protein-folding team.

Over the past 50 years, ever since Christian Anfinsen’s famous speech, scientists have tried speed up the analysis of protein structure by using complex mathematical models run on high-powered computers. “What you do is essentially try to create a digital twin of the protein in your computer, and then try to manipulate it,” says John Moult, a professor of cell biology and molecular genetics at the University of Maryland and a pioneer in using mathematical algorithms to predict protein structures from their DNA sequences. The problem is, these predicted folding patterns were frequently wrong, failing to match the structures scientists found through X-ray crystallography. In fact, until about 10 years ago, few models were able to accurately predict more than about a third of a large protein’s shape.

Some protein-folding simulations also take up tremendous amounts of computing power. In the year 2000, researchers created a “citizens science” project called Fold@home in which people could donate the idle processing capacity of their personal computers and game consoles to run a protein-folding simulation. All those devices, chained together through the Internet, created one of the world’s most powerful virtual supercomputers. The hope was that this would allow researchers to escape Levinthal’s Paradox—to speed up the time it would take to hit upon the accurate protein structures through random trial and error. The project, which is still running, has provided data for more than 225 scientific papers on proteins implicated in a number of diseases.

But despite having access to so much processing power, Fold@home is still mired in Levinthal's Paradox: It is trying to find a protein structure by searching through all possible permutations. The holy grail of protein folding is to skip this laborious search and to instead discover elusive patterns that link a protein’s DNA sequence to its structure—allowing a computer to take a radical shortcut, leaping directly from genetics to the correct shape.

Games with a serious purpose

Demis Hassabis’s interest in protein folding began, as many of Hassabis’s passions do, with a game. Hassabis is a former chess prodigy, a master by the time he was 13 and at one time ranked second in the world for his age. His love of chess fed a fascination with two things: game design and the inner mechanisms of his own mind. He began working for a video games company while still in high school and, after studying computer science at the University of Cambridge, founded his own computer games startup, Elixir Studios, in 1998.

Despite producing two award-winning games, Elixir eventually sold off its intellectual property and shut down, and Hassabis went on to get a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience from University College London. By then, he had already embarked on the crusade that would lead him to cofound DeepMind in 2010: the creation of artificial general intelligence—software capable of learning to perform many disparate tasks as well or better than people. DeepMind’s lofty goal, Hassabis once said, was “to solve intelligence, and then use it to solve everything else.” Hassabis already had an inkling that protein folding just might be one of those first “everything elses.”

Hassabis was doing a postdoc at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2009 when he heard about an online game called Foldit. Foldit was designed by researchers at the University of Washington and, like Fold@home, it was a “citizens science” project for protein folding. But instead of yoking together idle microchips, Foldit was designed to harness idle brains.

Foldit is a puzzle-like game in which human players, without any knowledge of biology, compete to fold proteins, earning points for creating shapes that are plausible. Researchers then analyze the highest-scoring designs to see if they can help complete unsolved protein structures. The game has attracted tens of thousands of players and, in a number of documented cases, produced better protein structures than protein-folding computer algorithms. “I thought it was fascinating from the standpoint of, can we use the addictiveness of games and the joy of them, and in the background not only are they having fun, but they are doing something useful for science,” Hassabis says.

But there was another reason Foldit would continue to capture Hassabis’s imagination. Games are a particularly good arena for a kind of A.I. training called reinforcement learning. This is where software learns from experience, essentially by trial and error, to get better at a task. In a computer game, software can experiment endlessly, playing over and over again, improving gradually until it reaches superhuman skill, without causing any real-world harm. Games also have ready-made and unambiguous ways to tell if a particular action or set of actions is effective: points and wins. Those metrics provide a very clear way to benchmark performance—something that doesn’t exist for many real-world problems, where the most effective move may be far more ambiguous and the entire concept of “winning” may not apply.

DeepMind was founded largely on the promise of combining reinforcement learning with a kind of A.I. called deep learning. Deep learning is A.I. based on neural networks—a kind of software loosely based on how the human brain works. In this case, instead of networks of actual nerve cells, the software has a bunch of virtual neurons, arranged in a hierarchy where an initial input layer takes in some data, applies a weighting to it, and passes it along to the middle layers, which do the same in turn, until it is eventually passed to an output layer that sums up all the weighted signals and uses that to produce a result. The network adjusts these weights until it can produce a desired outcome—such as accurately identifying photos of cats or winning a game of chess. It’s called “deep learning” not because the insights it produces are necessarily profound—although they can be—but because the network consists of many layers and so can be said to have depth.

DeepMind’s initial success came in using this “deep reinforcement learning” to create software that taught itself to play classic Atari computer games, such as Pong, Breakout, and Space Invaders, at superhuman levels. It was this achievement that helped get DeepMind noticed by big technology firms, including Google, which bought it for a reported £400 million (more than $600 million at the time) in 2014. It then turned its attention to Go, eventually creating the system AlphaGo, which defeated Sedol in 2016. DeepMind went on to create a more general version of that system, called AlphaZero, that could learn to play almost any two-player, turn-based game in which players have perfect information (so there is no element of chance or hidden information, such as face-down cards or hidden positions) at superhuman levels. Last year, it also built a system that could beat top human professional e-sports players at the highly complex real-time strategy game Starcraft 2.

But Hassabis says he always saw the company’s work with games as a way to perfect A.I. methods so they could be applied to real-world challenges—especially in science. “Games are just a training ground, but a training ground for what exactly? For creating new knowledge,” he says.

DeepMind is not a traditional business, with products and customers. Instead, it is essentially a research lab that tries to advance the frontiers of artificial intelligence. Many of the methods it develops, it publishes openly for anyone to use or build upon. But some of its advances are useful for its sister company, Google.

DeepMind has a whole team of engineers and scientists that help Google incorporate cutting-edge A.I. into its products. DeepMind’s technology has found its way into everything from Google Maps to the company’s digital assistant to the system that helps manage battery power on Android phones. Google pays DeepMind for this help, and Alphabet, its parent company, continues to absorb the additional losses that DeepMind generates. Those are not insignificant: The company lost £470 million in 2018 (about $510 million at the time), the last year for which its annual financial statements are publicly available through the U.K. business registry Companies House.

But DeepMind, which now employs more than 1,000 people, also has a whole other division that works only on scientific applications of A.I. It is headed by Pushmeet Kohli, a 39-year-old native of India, who worked on A.I. research for Microsoft before joining DeepMind. He says that DeepMind’s aim is to try to solve “root node” problems—data science-speak for saying it wants to take on issues that are fundamental to unlocking many different scientific avenues. Protein folding is one of these root nodes, Kohli says.

“The Olympics of protein folding”

In 1994, at a time when many scientists were first starting to use sophisticated computer algorithms to try to predict how proteins would fold, Moult, the University of Maryland biologist, decided to create a competition that could provide an unbiased way of assessing which of these algorithms was best. He called this competition the Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP, for short), and it has been held biennially ever since.

It works like this: The Protein Structure Prediction Center, the organization that runs CASP and which is funded through the U.S. National Institute of General Medical Sciences, persuades researchers who do X-ray crystallography and other empirical studies to provide it with protein structures that have not yet been published anywhere, asking them to refrain from making the structures public until after the CASP competition. CASP then gives the DNA sequences of these proteins to the contestants, who use their algorithms to predict the protein’s structure. CASP then judges how close the predictions are to the actual structure the X-ray crystallographers and experimentalists found. The algorithms are then ranked by their average performance across all the proteins. “I call it the Olympics of protein folding,” Hassabis says. And, in 2016, shortly after AlphaGo beat Sedol, DeepMind set out to win the gold medal.

DeepMind established a small, crack team of a half-dozen machine learning researchers and engineers to work on the problem. “It’s part of our philosophy that we start with generalists,” Hassabis says. The company does not suffer from a lack of brain power. “Ex-physicists, ex-biologists, we just have them lying around generally,” Hassabis says with a wry smile. “They never know when their previous expertise suddenly is going to become useful.” Eventually the team grew to about 20 people.

Still, DeepMind decided it would be helpful to have at least one true protein-folding expert onboard. It found one in John Jumper. Skinny, with a mop of asymmetrically styled brown hair, Jumper is a boyish 35 and looks a bit like the bass guitarist in a late-1990s high school garage band. He earned a master’s degree in theoretical condensed matter physics from Cambridge before going on to work at D.E. Shaw Research in New York City, an independent research lab founded by hedge fund billionaire David Shaw. The lab specializes in computational biology, including the simulation of proteins. Jumper later got his Ph.D. in computational biophysics from the University of Chicago, studying under Karl Freed and Tobin Sosnick, two scientists known for advances in protein-fold modeling. “I had heard this rumor that DeepMind was interested in protein problems,” he says. He applied and got the job.

Hassabis’s and the DeepMind team’s first instinct was that protein folding could be solved in exactly the same way as Go—with deep reinforcement learning. But this proved problematic: For one thing, there were even more possible fold configurations than there are moves in Go. More importantly, DeepMind had mastered Go in large part by getting its A.I. system, AlphaGo, to play games against itself. “There isn’t quite the right analogy for that because protein folding is not a two-player game,” Hassabis says. “You’re sort of playing against Nature.”

DeepMind soon established that there was a simpler way of making progress using a kind of A.I. training known as supervised deep learning. This is the sort of A.I. used in most business applications: From an established set of data inputs and corresponding outputs, a neural network learns how to match a given input to a given output. In this case, DeepMind had the protein structures—currently about 170,000 of them—that are publicly available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), a public repository of all known three-dimensional protein shapes and their genetic sequences, to use as training data.

Some biologists had already used supervised deep learning to predict how proteins would fold. But the best of these A.I. systems were right only about 50% of the time, which wasn’t particularly helpful to biologists or medical researchers—especially since, for a protein whose structure was unknown, they had no way of determining whether a particular prediction was correct.

One promising technique rested on the idea that proteins can be grouped into families based on their evolutionary history. And within these families, it is possible to find pairs of amino acids that are distant from one another in a DNA sequence, yet seem to mutate at the same time. This phenomenon, which is called “coevolution,” is helpful because coevolved proteins are likely to be in contact within the protein’s folded structure. Jinbo Xu, a scientist at the Toyota Technological Institute in Chicago, pioneered using deep learning on this coevolutionary data to predict amino acid contacts. The approach is a bit like finding just the dots in a connect-the-dots game. Scientists still had to use other software to try to figure out the lines between those dots—and often they got this wrong. Sometimes they didn’t even get the dots right.

For the 2018 CASP competition, DeepMind took these basic ideas about coevolution and contact prediction but added two important twists. First, rather than trying to determine if two amino acids were in contact, a binary output (either the pair is in contact or isn’t), it decided to ask the algorithm to predict the distance between all the amino acid pairs in the protein.

To most molecular biologists, such an approach seemed counterintuitive—although Xu, to his credit, had independently proposed a similar method. After all, it was contact that mattered most. But to DeepMind’s deep learning experts it was immediately obvious that distance was a much better metric for a neural network to work on, Kohli says. “It is just a fundamental part of deep learning that if you have some uncertainty associated with a decision, it is much better to have the neural network incorporate that uncertainty and decide what to do about it,” he says. Distance, unlike contact, was a richer piece of information the network could adjust and play with.

The other twist DeepMind came up with was a second neural network that predicted the angles between amino acid pairs. With these two factors—distance and angles—DeepMind’s algorithm was able to work out a rough outline of a protein’s likely structure. It then used a different, non-A.I. algorithm to refine this structure. Putting these components together into a system it called AlphaFold, DeepMind crushed the competition in the 2018 CASP (called CASP13 because it was the 13th of the biennial contests). On the hardest set of 43 proteins in the competition, AlphaFold got the highest score on 25 of them. The next closest team scored highest on just three. The results shook the entire field: If there had been any doubt about whether deep learning methods were the most promising way to crack the protein-folding problem, AlphaFold ended them.

Going back to the whiteboard

Still, DeepMind was nowhere close to Hassabis’s goal: solving the protein-folding problem. AlphaFold was fairly inaccurate almost half the time. And, of the 104 protein targets in CASP13, it achieved results that were as good as X-ray crystallography in only about three cases. “We didn’t just want to be the best at this according to CASP, we wanted to be good at this. We actually want a system that matters to biologists,” Jumper says.

No sooner had the CASP 2018 results been announced than DeepMind redoubled its efforts: Jumper was put in charge of the expanded team. Rather than simply trying to build on AlphaFold, making incremental improvements, the team went back to the whiteboard and started to brainstorm radically different ideas that they hoped would be able to bring the software closer to the kind of accuracy X-ray crystallography yielded.

What followed, Jumper says, was one of scariest and most depressing periods of the entire project: nothing worked. “We spent three months not getting any better than our CASP13 results and starting to really panic,” he says. But then, a few of the things the researchers were trying produced a slight improvement—and within six months the system was notably better than the original AlphaFold. This pattern would continue throughout the next two years, Jumper says: three months of nothing, followed by three months of rapid progress, followed by yet another plateau.

Hassabis says a similar pattern had occurred with previous DeepMind projects, including its work on Go and the complex, real-time strategy video game Starcraft 2. The company’s management strategy for overcoming this, he says, is to alternate between two different ways of working. The first, which Hassabis calls “strike mode,” involves pushing the team as hard as possible to wring every ounce of performance out of an existing system. Then, when the gains from the all-out effort seem to be exhausted, he shifts gears into what he calls “creative mode.” During this period, Hassabis no longer presses the team on performance—in fact, he tolerates and even expects some temporary declines—in order to give the researchers and engineers the space to tinker with new ideas and try novel approaches. “You want to encourage as many crazy ideas as possible, brainstorming,” he says. This often leads to another leap forward in performance, allowing the team to switch back into strike mode.

A big birthday present

On Nov. 21 of 2019, Kathryn Tunyasuvunakool, a researcher at DeepMind who works on the protein folding team, turned 30. The day would prove to be memorable for another reason too. Tunyasuvunakool, who has a Ph.D. in computational biology from the University of Oxford, was the person on the team in charge of developing new test sets for the protein-folding A.I., now dubbed AlphaFold 2, that DeepMind was developing for the 2020 CASP competition. That morning, when she turned on her office computer, she received an assessment of the system’s predictions on a batch of about 50 protein sequences—all of them only recently added to the Protein Data Bank. She did a double take. AlphaFold 2 had been improving, but on this set of proteins the results were startlingly good—predicting the structure in many cases to within 1.5 angstroms, a distance equivalent to a tenth of a nanometer, or about the width of an atom.

Tunyasuvunakool, who calls herself “the team’s pessimist,” says her first response was not elation, but nausea. “I was feeling quite scared,” she says. The results were so good she was certain she had made a mistake—that when she was preparing the test set, she must have inadvertently allowed several proteins that the A.I. had already seen in the training data to slip in. That would have allowed AlphaFold 2 to essentially cheat, easily predicting the exact structure. Tunyasuvunakool recalls sitting in DeepMind’s cafeteria overlooking London’s St. Pancras Station and drinking cup after cup of herbal tea in an effort to calm herself. She and other team members then spent the rest of that day and late into the evening, and several days more, sitting at their workstations, painstakingly combing through AlphaFold 2’s training data to try to find the mistake.

There wasn’t one. In fact, the new system had made a giant leap forward in performance. AlphaFold 2 was completely different from its predecessor. Rather than an assemblage of components—one to predict the distance between amino acids and another to forecast the angles, with a third piece of software to tie them together —the A.I. now used a single neural network to reason directly from the DNA sequence. While the system still took in evolutionary information—figuring out if the protein in question had a likely common ancestor to others it had seen before, and scrutinizing the alignment between the target protein’s DNA sequence and other known sequences—it no longer needed explicit data about which amino acid pairs evolved together. “Instead of providing more information, we actually provided less,” Jumper says. The system was free to draw its own insights about when ancestry might determine a portion of the protein’s shape and when it might depart more radically from that heritage. In other words, it developed a kind of intuition based on its experience, in much the same way a veteran human scientist might.

At the heart of the new system was a mechanism called "attention." Attention, as the name implies, is a way to get a deep learning system to focus on a certain set of inputs and weigh those more heavily. For a cat identification system, for instance, the system might learn to pay attention to the shape of the ears and also learn to look for evidence of whiskers near the nose. Jumper compares what AlphaFold 2 does to the process of solving a jigsaw puzzle where “you can snap together certain pieces and be pretty sure of it, and then what you end up with are different local islands of solution, and then you figure out how to join these up.” The middle of the network, Jumper says, has learned to reason about geometry and space and how to join up those amino acid pairs it thinks are close together based on its analysis of the DNA sequences.

DeepMind trained AlphaFold 2 on 128 “tensor processing cores,” the number-crunching brains found on 16 special computer chips engineered for deep learning that Google designed and uses in its data centers, running continuously for what the company says was a few weeks. (These 128 specialized A.I. cores are about equivalent to 100 to 200 of the powerful graphics processing chips that deliver eye-popping animation on an Xbox or PlayStation.) Once trained, the system can take a DNA sequence and spit out a complete structure prediction “in a matter of days,” the company says.

Among AlphaFold 2’s advantages over its predecessor is a confidence gauge: The system produces a score for how sure it is of its own predictions for each amino acid in a structure. This metric is crucial if AlphaFold 2 is going to be useful to biologists and medical researchers who will need to know when they can reasonably rely on the model and when to have more caution.

Despite the stunning test results, DeepMind was still not certain how good AlphaFold 2 was. But they got an important clue when the coronavirus pandemic struck. In March of this year, AlphaFold 2 was able to predict the structure for six understudied proteins associated with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, one of which scientists have since confirmed using an empirical method called cryogenic electron microscopy. It was a powerful glimpse of the kind of real-world impact DeepMind hopes AlphaFold 2 will soon have.

An astonishing result

The CASP competition takes place between May and August. The Protein Structure Prediction Center releases batches of target proteins, and contestants then submit their structure predictions for evaluation. The rankings for this year’s competition were announced on Nov. 30.

Each prediction is scored using a metric called “global distance test total score,” or GDT for short, that in effect looks at how close, in angstroms, it is to a structure obtained by empirical methods such as X-ray crystallography or electron microscope. A score of 100 is perfect, but anything at 90 or above is considered equivalent to the empirical methods, Moult, the CASP director, says. The proteins are also classed into groups based on how difficult the CASP organizers think it is to get the structure.

When Moult saw AlphaFold 2’s results he was incredulous. Like Tunyasuvunakool months earlier, his initial thought was that there might be a mistake. Maybe some of the protein sequences in the competition had been published before? Or maybe DeepMind had somehow managed to get hold of a cache of unpublished data?

As a test, he asked Andrei Lupas, director of the department of protein evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tuebingen, Germany, to conduct an experiment. Lupas would ask AlphaFold 2 to predict a structure that he knew for certain had never been seen before because Lupas had never been able to work out from X-ray crystallography what a key piece of the protein looked like. For almost a decade, Lupas had puzzled over this missing link, but the correct shape had eluded him. Now, with AlphaFold’s prediction as a guide, Lupas says, he went back to the X-ray data. “The correct structure just fell out within half an hour,” he says. “It was astonishing.”

Since DeepMind’s success in 2018’s CASP, many academic researchers have flocked to deep learning techniques. As a result, the rest of the field’s performance has improved: On a median difficulty target, the other competitors now have an average best prediction GDT of 75, up 10 points from two years ago. But there was no comparison to AlphaFold 2: It scored a median 92 GDT across all proteins, and even on the most difficult proteins it achieved a median score of 87 GDT. Moult says AlphaFold 2’s predictions are “on par with empirical methods,” such as X-ray crystallography. That conclusion lead CASP to make a momentous declaration on Monday, Nov. 30: The 50-year-old protein-folding problem had been solved.

Venki Ramakrishnan, a Nobel Prize–winning structural biologist who is also the current president of The Royal Society, Britain’s most prestigious scientific body, says AlphaFold 2 “represents a stunning advance” in protein folding. With AlphaFold 2, expensive and time-consuming empirical analysis with methods like X-ray crystallography and electron microscopes may become a thing of the past.

Janet Thornton, an expert in protein structure and former director of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory’s European Bioinformatics Institute, says that DeepMind’s breakthrough will allow scientists to map the entire human “proteome”—all the proteins found within the human body. Currently only a quarter of these proteins have been used as targets for drugs, but having the structure for the rest would create vast opportunities for the development of new therapies. She also says the A.I. software could enable protein engineering that might aid in sustainability efforts, allowing scientists to potentially create new crop strains that provide more nutritional value per acre of land planted, and also possibly allowing for the advent of enzymes that could digest plastic.

For now, though, the question remains about how exactly DeepMind will make AlphaFold 2 available. Hassabis says the company is committed to ensuring the software can “make the maximal positive societal impact.” But he says it has not yet determined how to do that, saying only that it will make an announcement sometime next year. Hassabis also tells Fortune that DeepMind is considering how it might be able to build a commercial product or partnership around the system. “This should be hugely useful for the drug discovery process and therefore Big Pharma,” he says. But exactly what form this commercial offering will take, he says, has not yet been decided either.

A commercial venture would be marked departure for DeepMind, which, since its sale to Alphabet, has not had to worry about generating revenue. The company briefly set up a division called DeepMind Health that was working with the U.K.’s National Health Service on an app that could identify hospital patients who were at risk of developing acute kidney injury. But the effort became embroiled in a controversy after news reports revealed DeepMind's hospital partner had violated the U.K. data protection laws by giving the company access to millions of patients’ medical records. In 2019, DeepMind Health was formally absorbed into a new Google health division. At the time, DeepMind said cleaving off its health effort would allow it to remain true to its research roots without the distraction of having to build a commercial unit that might replicate areas, such as data security and customer support, where Google already had expertise.

Of course, if DeepMind were to launch a commercial product, it would not be the first A.I. research company to do so: OpenAI, the San Francisco–based research company that is perhaps DeepMind’s closest rival, has become increasingly business-oriented. Last year, OpenAI launched its first commercial product, an interface that lets companies use an A.I. that composes long passages of coherent text from a short, human-written prompt. The business value of that A.I., called GPT-3, remains unproven, while DeepMind’s AlphaFold 2 could have an immediate bottom-line impact for a pharmaceutical company or biotechnology startup. At a time when antitrust regulators are probing Alphabet, having a viable commercial product could be a good insurance policy for DeepMind in the event it ever loses the unconditional support of its deep-pocketed parent in some future breakup of the Googleplex.

One thing is certain: DeepMind isn’t done with protein folding. The CASP competition was set up around predicting the structure of single proteins. But in biology and medicine, it is usually protein interactions that researchers really care about. How does one protein bind with another or with a particular small molecule? Exactly how does an enzyme break a protein apart? The problem of predicting these interactions and bindings will likely become the primary focus of future CASP competitions, Moult says. And Jumper says DeepMind plans to work on those challenges next.

Reverberations from AlphaFold 2’s success are certain to be felt in areas far removed from protein folding, too, encouraging others to apply deep learning to big scientific questions: finding new subatomic particles, probing the secrets of dark matter, mastering nuclear fusion, or creating room-temperature superconductors. DeepMind has an active effort already underway on astrophysics, Kohli says. Facebook’s A.I. researchers just launched a deep learning project aimed at finding new chemical catalysts. Protein folding is the first foundational scientific mystery to fall to the power of artificial intelligence. It won’t be the last.