硅谷造肉记

|

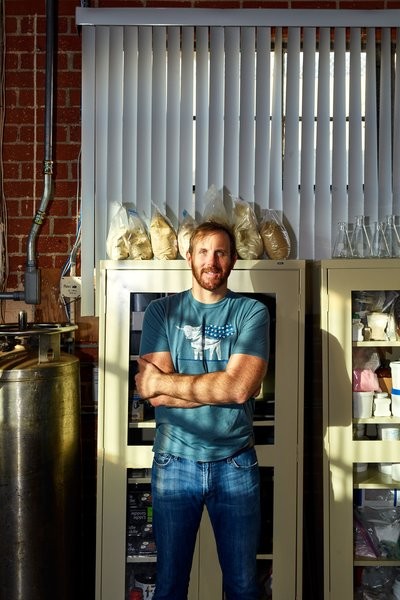

去年8月,硅谷最热门的创业公司完成了一轮1700万美元融资。虽然只是A轮,但引来不少科技界大佬。“我没抢过理查德·布兰森和比尔·盖茨,所以败下阵来,”一家没机会投资的天使基金管理受托人乔迪·拉希哀叹道。曾投资特斯拉和SpaceX等知名企业的风险投资公司德丰杰领投,一位合伙人称这家公司的产品是“巨大的技术革新”。 这家初创公司技术领先的产品到底是什么?是肉——仅在美国的销售额就超过2000亿美元,也是西方饮食里的重要元素。但这家公司的产品之所以具有革新性,关键在于其研究内容不是肉能制成哪些食物,而是如何生产肉。这家让投资界垂涎不已的公司名叫Memphis Meats, 目标是不用动物生产肉。 这种拯救世界的创意立刻引发硅谷关注,因为科技从业者相信只有技术才能解决当前的大问题:养活增长迅速急需蛋白质供应的人口,又不能引发全球动荡。畜牧业在全球温室气体排放中占比高达14.5%,所以不靠畜牧业生产肉类是关键。谷歌创始人是这么描述无动物成分肉类前景的:“可以改变我们看待世界的方式”,谷歌联合创始人谢尔盖·布林说。“我想寻找即将可行的技术,一旦成功就是革新性的。” 实际上在很多硅谷工程师看来,制造肉类的流程效率太低,已经到了颠覆的时候。看起来,通过动物转化为肌肉组织非常不合适。每获得一磅可供使用的牛肉,要消耗26磅饲料。在崇尚高效的文化里,如此浪费简直让人不可容忍。 |

In August one of Silicon Valley’s hottest startups closed a $17 million round of funding. The Series A had attracted some of the biggest names in tech. “I got closed out because of Richard Branson and Bill Gates,” bemoaned Jody Rasch, the managing trustee of an angel fund that wasn’t able to buy in. Venture capital firm DFJ—which has backed the likes of Tesla and SpaceX—led the round, with one of its then-partners calling the nascent company’s work an “enormous technological shift.” The cutting-edge product the startup was trying to develop? Meat—the food whose more than $200 billion in U.S. sales has come to be the defining element of the Western diet. But what made this company’s work so revolutionary was not what it was trying to make so much as how it was attempting to do it. Memphis Meats, the brainchild that had the startup-investor class salivating, was aiming to remove animals from the process of meat production altogether. It’s the type of world-saving vision that has oft captured the imagination of Silicon Valley—the kind of entrenched problem that technologists believe only technology can solve: feeding a fast-growing, protein-hungry global population in a way that doesn’t blow up the planet. Conjuring up meat without livestock—whose emissions are responsible for 14.5% of global greenhouse gases—is core to that effort. Just listen to how the progenitor of Googleyness itself describes the prospect of animal-free meat: “It has the capability to transform how we view our world,” Google cofounder Sergey Brin has said. “I like to look at technology opportunities where the technology seems like it’s on the cusp of viability, and if it succeeds there, it can be really transformative.” Indeed, in the eyes of many Silicon Valley engineers, meatmaking is a process that’s so inefficient it’s ripe for disruption. Animals, it seems, are lousy tools for converting matter into muscle tissue. Cows require a whopping 26 pounds of feed for every one pound of edible meat produced. In a culture obsessed with high performance, that is maddeningly wasteful. |

|

为什么不另辟蹊径呢?这就是Memphis Meats和其他一些初创公司努力的方向。Memphis Meats代表了一种可能,叫私包农业,科学家通过动物细胞研究“人工”或“干净”的肉。还有些公司则努力让植物口感接近肉质。他们的目标不是做出素食主义者喜欢的蔬菜肉饼,而是高级素肉饼,肉食爱好者带着参加邻居的烧烤聚会也毫无问题。(当然只是基本上没问题。)这类公司包括Beyond Meat和竞争对手Impossible Foods,其中Impossible Foods从盖茨和科拉斯创投等处融资多达2.75亿美元。在克罗格之类主流商场的肉制品区域,已经能找到植物肉饼,从名厨David Chang执掌的Momofuku Nishi到TGI Fridays餐厅,今年1月开始菜单上也都开始出现植物肉饼。 细胞农业和植物制肉公司目标是一致的,只是实现的路径很不一样。推崇植物肉饼的人认为人工制成的肉无法规模化;而Memphis Meats和其他反对者认为,不管怎么处理植物制品,吃起来永远是植物味道。但两伙人最终目标是一致的:打造无动物肉制品的未来,人们不用再牺牲动物,不用充满愧疚和妥协。 替代肉厂商指出,植物奶制品已呈爆发性增长,占美国零售市场份额近10%,可见市场潜力。“我想说,人们不用非要选择吃什么,” Memphis首席执行官兼联合创始人乌玛·瓦莱蒂表示,“但可以选择加工上桌的过程。” 为了让选择更轻松,新一代农业创业家首先要澄清几点,首先是说清楚“肉类”意味着什么。Beyond Meat首席执行官伊森·布朗表示,希望人们认为“从组成成分”看待肉类,而不是只看来源。这种转变不仅限于认知层面,更是科学意义上的,是将肉类拆分到细胞层面理解。 但要让人们接受并不容易,抵制者也不少。其中有些人似乎对干扰自然很生气。“这伙人就是想重新定义肉类,都是些不吃肉的人,”家族从事肉类行业超过150年的苏珊娜·斯特拉斯堡说。“真正的问题是,他们是想养活人类,还是纯粹为了满足自我需求。” 价值2400美元的肉饼 在培养皿里培养细胞听起来像科幻小说情节,但这种技术的基础早已出现,已经几十年了,基本上跟医学上培养人类细胞和组织差不多。Memphis Meats的瓦莱蒂在梅奥诊所接受培训当心脏病专家时就开始想,能不能用同样方法培养肉类。之后他在双子城执业,病人心脏病发就往心脏注射干细胞。 麻烦在于要降低成本,要降到能做肉饼,而不是治疗心脏病的成本。Memphis Meats制出一磅约2400美元的人工肉饼,进展相当显著。去年成本还是一磅18000美元,2013年荷兰科学家马克·珀斯特制成的第一个人工肉饼花费超过30万美元。 降低成本最大的障碍是细胞介质,也即细胞的食物。Finless Foods首席执行官麦克·塞尔顿告诉我,公司做出第一份鱼肉炸丸子(价格:一磅19000美元)时,相关材料占成本99%。动物细胞标准介质重要组成部分是胎牛血清(FBS),提取自牛胚胎的心脏,母牛怀胎时宰杀获得。即便不是动物权益保护者,也能看出为什么这种方法很难令行业接受。所以现在研发的重点是寻找替代手段。塞尔顿表示Finless已经将FBS的使用减少一半,方法是将血清中关键成分通过发酵增加产量,Memphis表示已经找到不需要FBS的方式,但不愿透露具体使用材料,因为涉及专利问题。 即便科学家发誓不用FBS,有一种顾客可能还是不会接受人工肉,即严格素食主义者,因为制作过程中不可能彻底放弃动物。人工肉制造商还是得首先从动物身上提取细胞,哪怕只是活体切片,不必再用宰杀方式。 不过珀斯特表示,没想让素食主义者和严格素食者接受人工肉。他相信如果强制推广只会适得其反。“选择植物食品还是更有效率,”60岁的创业家珀斯特表示。 为什么不放弃细胞培养的途径,用豆类或胡萝卜之类制作更美味的肉饼呢?“植物制肉产品已经出现40年了,”他表示,“但基本上还是替代品,跟真实的肉差别还很大。我们相信选用植物产品不会有多大改变。” 我还没尝过细胞农业做出的肉类产品,其实真正尝过的人极少,因为市面上还没有。一方面,推动此类产品进入商场还要通过严格的监管流程,另一方面,制造商如何获得许可继续在该科学领域继续探索也不明确。美国食品药品管理局监督通过发酵制成的产品,这也是生化领域的关键过程,同时美国农业部负责监管肉类质量和安全。在杜邦公司监管合规部门工作的文森特·西瓦尔特表示,如果相关公司现在申请许可,最顺利的情况下也要两年才能通过。 “大部分公司都太乐观了,” MosaMeat联合创始人马克·珀斯特说。 从2008年开始,珀斯特就在研究人工肉,现在从他的公司MosaMeat发展情况,加上过去九年的经验来看,他对破除障碍扩大规模有些悲观。挑战在于找到FBS的替代品,大幅降低成本,提升细胞生长速度,还有找到合适的监管路径,各领域互相交织。科学方面还有个障碍:让细胞按照固定的结构生长,因为未来目标显然不只是制作肉馅。想让培养皿里的动物细胞长成牛排的样子?没那么容易。 关于新产品多久能真正进入市场,珀斯特不愿多猜测。但在写本篇文章过程中,我听过各种对日期的推断,从明年到超过十年都有。“大部分公司都太乐观了,”珀斯特有些沮丧地说。“他们很理想化。”少数几位采访对象甚至将人工肉跟太空探索相提并论;他们认为,人类建立火星殖民地需要这项技术。几乎所有从事该领域的科学家都会陷入宏大的概念中,即科学可以借鉴世界上最大的问题。“我不愿叫自己理想主义者,”珀斯特说,“但我努力的目标是产生社会影响。我猜这也是种理想主义。” 血色将至 如果对细胞农业来说扩大规模是限制因素,那么植物肉遇到的挑战更严峻:如何让高粱口感像西冷牛排。“制造完美植物肉的道路上不是非黑即白,”塞尔顿表示。即便你能让园林乳液看起来像肉,甚至放进嘴里尝起来像肉,这么说吧,想尝起来像真正的肉还是完全不一样。 Beyond Meat的研究在名叫“曼哈顿海滩计划”的实验室中进行,就在离加州埃尔塞贡多总部不远的街上。“我希望人们能明白这件事对全球的重要意义,”首席执行官伊森·布朗说。“我们有最聪明的科学家,也会提供这项工作需要的资金,”他补充说。“这是全球面临的问题,不只关乎饮食选择。” Beyond Meat从植物中提取蛋白,通过加热、冷却和加压等方式改变蛋白的性状,模仿动物肌肉。“如果不需要动物或动物器官,为什么还非要吃动物呢,”布朗表示。“动物只是从植物中吸取所有材料,按照特定方式重新组合而已。” 布朗承认团队还有很多事要做。“我比其他人更挑剔,”他说,“我认为前方还有很长的路要走。”布朗总在提醒有很多事要做,他办公室里挂着一幅海报,上面写着“不过是味道好点的素火鸡”——来自2015年一位评论家的严厉批评。 对研究替代肉类的人们来说,第一步就是充分理解想要取代的是什么,不只是味道和口感,还有为何会产生特定的声音,烹制过程中为何会变色,一位科学家向我描述说,烹饪就像“肉类的戏剧”。 |

So why not take them out of the equation? That’s precisely what Memphis Meats and a cohort of other startups are trying to do. Memphis represents one possible path called cellular agriculture, in which scientists are trying to grow what has become known as “cultured” or “clean” meat from animal cells. Others are trying to make plants taste like meat. The goal here is not to create your vegan cousin’s Boca Burger of yore, but instead a veggie patty that a hard-core carnivore wouldn’t be ashamed to bring to a neighborhood barbecue. (In principle, anyway.) Companies in this camp include Beyond Meat and its rival Impossible Foods—which has raised an eye-popping $275 million from the likes of Gates and Khosla Ventures. These more convincing plant burgers can already be found in the meat aisle of mainstream grocery stores like Kroger and are on the menus of restaurants ranging from famed chef David Chang’s Momofuku Nishi to TGI Fridays starting in January. Both cellular ag and plant-based meat companies have the same goal—but their paths to get there couldn’t be more different. The plant-burger boosters don’t believe cultured meat will ever be able to scale; Memphis Meats and its brethren counter that plants—no matter what you do to them—will always taste like plants. But both groups share the same ultimate vision: to create the post-animal economy—a world free of consumer sacrifice, guilt, and compromise. As a sign of the market’s potential, alternative meat producers point to the explosive growth plant-based milk has made in the dairy aisle, now capturing almost 10% of U.S. retail sales by volume. “I want to be able to say you don’t have to make a choice in what you’re eating,” Memphis CEO and cofounder Uma Valeti says, “but you can make a choice on the process of how it goes to the table.” Hoping to make that choice easier, the new agripreneurs are tackling semantics first—redefining what “meat” means. Beyond Meat CEO Ethan Brown says he’d like to get people to think about meat “in terms of its composition” rather than its origin. The reframing isn’t just an epistemological one, but also a scientific one, reducing meat to its molecules. That won’t be an easy sell, and the movement has its detractors—some of whom seem miffed by the notion that anyone would try to mess with Mother Nature. “They want to make up their own dictionary version of what meat is, and these are people who do not eat meat,” says Suzanne Strassburger, whose family has been in the meat business for more than 150 years. “The real question is, are they feeding people or are they feeding egos.” The $2,400 Meatball Growing cells in Petri dishes sounds like the stuff of science fiction, but the basic elements of the science are actually decades old. It’s essentially the same process used in medicine to cultivate human cells and tissues. Memphis Meats’ Valeti started thinking about growing meat when he was training as a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic. Later, at his own practice in the Twin Cities, he began injecting stem cells into patients’ hearts to regrow muscle after a heart attack. The trouble is getting the economics to work for a hamburger, not a human heart. Memphis Meats created a cultured meatball that costs about $2,400 a pound to produce, and that was notable progress. The cost last year was $18,000 a pound—down from the more than $300,000 spent on the first cultured burger made in 2013 by Dutch scientist Mark Post. The biggest hurdle to lowering the cost is the cellular medium, the stuff the cells feed on. Mike Selden, CEO of Finless Foods, told me that this substrate contributed 99% of the cost of growing the company’s first fish croquettes (price tag: $19,000 per pound). A critical part of the standard medium that works across animal cell types is fetal bovine serum (FBS), which is extracted from the heart of a calf fetus when its mother is pregnant at slaughter. One does not have to be an animal rights activist to see why this is not an acceptable option for the industry. As a result, much of the R&D focus right now is on finding an alternative. Selden says Finless has cut its FBS use down by half by reproducing the essential components of the serum through fermentation, and Memphis says it has come up with an FBS-free medium but won’t reveal what it’s using instead because it’s proprietary. But even if scientists forswear FBS, cultured meat may not be wholly acceptable to one group of potential customers—vegans—because the animal can never be completely removed from the process. Cultured meat producers still have to source the first set of cells from an animal—even if it’s just a small biopsy that doesn’t require slaughter. Post, however, says he’s not trying to turn vegetarians and vegans into cultured meat consumers anyway. In fact, he believes, it would be counterproductive. “Eating a plant-based diet is always going to be more efficient,” says the 60-year-old entrepreneur. Then why not forget the cell-culture route and try to make better burgers from the likes of peas and carrots? “We’ve seen plant-based products for 40 years,” he says, “but they are basically still substitutes that are very different from the real thing. We believe plant-based options alone are not going to make a big difference.” I never got to taste a meat product made from cellular agriculture—very few people ever have—because none are on the market. For one thing, there are significant regulatory challenges to getting them to grocery store shelves, and it’s unclear how a manufacturer seeking approval would even proceed in this uncharted area of science. The FDA oversees products made through fermentation—a key process used in the biotech sector—but the USDA is responsible for regulating meat quality and safety. Vincent Sewalt, who works in regulatory compliance at DuPont, has said if a company started the approval process today it would take two years to get through in the very best-case scenario. “Most of the companies are overly optimistic,” says MosaMeat cofounder Mark Post. Post has been working on cultured meat since 2008, now through his company MosaMeat, and his experiences over the past nine years have made him somewhat cynical about the hurdles to scaling. The challenges of finding an alternative to FBS, bringing costs down massively, speeding up cell growth, and finding an appropriate regulatory pathway, have compounded one another. And there’s another scientific roadblock too: getting the cells to adhere to a certain fixed structure—assuming, that is, the aim is to produce more than ground chuck. Want your Petri-dish animal cells to end up shaped like a porterhouse? Not so easy. Post won’t put a timeline on how long the quest to get to market will take, but during my reporting I heard people throw out dates ranging from next year to more than a decade hence. “Most of the companies are overly optimistic,” Post says, ruefully. “They’re very idealistic.” A few sources even spoke of cultured meat in the context of space exploration; we need this technology to colonize Mars, they contend. For nearly all of these scientists, it has been hard not to get sucked into the grand notion that science can solve the world’s big problems. “I wouldn’t call myself an idealist,” says Post, “but I’m driven by the societal impact this can have. I guess that is idealism.” There Will Be Blood If scaling up is the limiting factor for cellular ag, the key challenge in making viable plant-based meat is more rudimentary: getting ingredients like sorghum to taste like sirloin. “There’s no black-and-white path to creating the perfect plant-based burger,” says Selden. Even if you can get a garden emulsion to look like meat, and even feel like meat in your mouth, it’s a whole different animal, so to speak, to get it to taste like the real thing. Beyond Meat’s research takes place at a lab dubbed the Manhattan Beach Project, down the street from its headquarters in El Segundo, Calif. “I wanted people to understand the global significance,” says CEO Ethan Brown. “We have the brightest scientists and we’re going to fund them at a level that this work deserves,” he adds. “This is a global problem, not a culinary choice.” Beyond Meat is taking the proteins from plant matter and resetting their bonds using heating, cooling, and pressure, so they mimic animal muscle. “Why go through all the trouble of using the animal or any organism if you don’t need to,” says Brown. “The animal is just taking all of that material from the plant and organizing it in a certain way.” Brown admits that his team still has a ways to go. “I’m more critical than others,” he says, “and I say we’re pretty far away.” As a constant reminder of the work that still needs to be done, Brown has a poster hanging in his office that reads “Slightly better Tofurky”—a harsh line from a critic in 2015. For anyone working on alternative meat, the first step is fully understanding what it is you are trying to replace—not just its taste and texture but why it makes that certain sound and changes color when it cooks, what one scientist described to me as the “theater of meat.” |

|

“刚开始我们在想肉类为什么能做到这样,即肉类的原理,” Impossible Foods首席执行官兼创始人帕特·布朗(跟同做植物肉的对手伊森·布朗没有关系)解释说。帕特·布朗在斯坦福大学担任生化专业荣誉教授,他开始研究肉类的时候跟研究疾病差不多。“科研人员不会说我想治好癌症,”他表示。“首先得了解普通细胞的工作原理。”他补充说,“这才是生物医学研究解决问题的方式。食品行业不会这么想问题。” Impossible的突破之处在于发现肉类本质在于原血红素——即血液中携带氧气的含铁分子,也是肉质呈红色的主要原因。原血红素也在豆科植物中存在,可将氮变为肥料。布朗花了一年多思考,以为能从大豆根瘤中提取出原血红素,但他错了。首先用覆盖泥土的植物就会影响食品安全,翻土收割过程中也会将碳释放到大气中对环境产生负面影响,而这是布朗极力避免的。 |

“We started out by basically asking how does meat do what it does—how does meat work,” explains Pat Brown, CEO and founder of Impossible Foods (and no relation to plant-based-meat rival Ethan Brown). Pat Brown, a professor emeritus of biochemistry at Stanford, started by studying meat in the way a researcher would study disease. “You don’t just say I want to cure this cancer,” he says. “You have to understand how normal cells work.” He adds, “That’s the way you solve a problem in biomedical research. And really that is not the mindset in the food world at all.” Impossible’s breakthrough was in discovering that meat’s essence comes from heme—the iron-rich molecule in blood that carries oxygen and is responsible for the deep-red color. Heme also exists in the roots of plants like legumes that turn nitrogen into fertilizer. Brown spent a little over a year thinking, incorrectly, that he could source heme by harvesting the root nodules of soybeans. But using the dirt-covered plants would be a food safety disaster—and turning the soil to harvest them would release carbon into the atmosphere, creating the kind of negative impact on the environment Brown is trying to offset. |

|

他再次从根本上寻找答案。三十年前他曾设计一种细菌菌株产生HIV酶,研究HIV病毒如何入侵人类细胞。“那是分子生物学家的绝招,”他说。所以几年前他试着用同样的方式制造原血红素,用蛋白质的植物基因注入酵母,然后将改良的酵母糖和营养物质刺激发酵。过程中,大部分酵母过滤掉,剩下原血红素。 在旧金山外的Impossible实验室,我尝了尝原血红素。有点像金属,一点也不美味,有点像狠咬嘴唇之后的味道。那股味道在我口中萦绕挺久,还很奇怪地让我想起酱油。我参观的那天,一个工程师团队正在处理生产过程中的问题,白色实验室外套上溅满了植物血液,看起来像惨案现场。“平常不是这样的,”Impossible研发总监克里斯·戴维斯连连道歉。五年前戴维斯接到布朗的电话时,还在同一个办公园区另一家公司研究生物燃料。 “我当时说,你知道我是做什么的,对吧?”戴维斯回忆说。而布朗只是解释说“牛是一种技术,将植物转变为人类喜欢的食物”。 |

He again went back to his roots for an answer. Thirty years ago he engineered a bacterial strain to produce an HIV enzyme so he could study how it enables HIV to infect human cells. “That’s the go-to move of a molecular biologist,” he says. So several years ago he tried the same approach for producing heme. He took the plant gene for the protein and inserted it into yeast, then fed the modified yeast sugars and nutrients to stimulate fermentation. In that process, most of the yeast is filtered out, leaving behind heme. At Impossible’s lab just outside San Francisco I try heme in its pure form. It was far from delicious, with a metallic quality that tastes like the aftermath of biting down hard on your lip. Its flavors lingered for a long time in my mouth and oddly reminded me of soy sauce. A team of engineers was sorting out a production problem the day I visited and their white lab coats, splattered with plant blood, made it appear like an especially horrific crime had just taken place. “This is not normal,” apologizes Chris Davis, Impossible’s director of R&D. Davis had been working on biofuels at a company in the same office park when he got a call from Brown five years ago. “I said you do know what I do, right?” Davis recalls telling him. Brown, says Davis, simply explained the “idea that the cow was just a technology to turn plants into something you want to eat.” |

|

研发团队主要工作是研究肉的味道,味道一小部分通过舌头感知,其他部分主要通过气味。肉类味道成分不是单一分子,因此Impossible的科学家要努力确定其中数百种化合物成分。戴维斯带着我从气相色谱质谱系统旁边走过,该系统能将气味分子分离出来,就像烹制真正的肉时一样。一位年轻的研究人员坐在机器旁边,记录下不同气味。例如,最近有位测试人员辨认出香菜、麦片、塑料和生马铃薯的香味。(嗯,好香。) 如果原血红素是Impossible肉饼的血,椰子油就是脂肪。小麦蛋白和马铃薯蛋白凝胶组成了肉的“肌肉” ——这是一种强壮的纤维,加入胶质凝胶后变得可塑。研发团队不断使用各种成分调整气味和质地,每天都有几次样品供员工品尝。让布朗尝时有时候可能会麻烦。这位创始人尝起味道来反应极其慢。“他一直是素食主义者,所以发挥不了什么作用,”戴维斯说,“他不知道肉什么味。” 戴维斯说,第一次制成的肉特别像腐臭的玉米粥。“很糟糕,”他说, “但比起之前的产品已经很好。”戴维斯解释说,实验室的规矩是,“不能毒死朋友,味道差点还能忍受。” |

Much of the work the R&D team focuses on is developing meat flavor, a minor fraction of which we perceive by way of our tongues and the rest via aroma. No single molecule makes up the smell of meat, so Impossible’s scientists are trying to identify the hundreds of compounds involved. Davis walks me by its gas chromatography mass spectrometry system, which separates out those molecules as a slab of real meat is cooking. A young researcher sits by the machine marking down notes about the varying aromas. One recent tester, for example, had identified the scents of cilantro, Cheerios, plastic, and raw potato. (Yum.) If heme is the Impossible Burger’s blood, then coconut oil is its fat. Wheat protein and potato protein gel make up the meat’s “muscle”—its sinewy fiber—and then gum gel is added to make the whole concoction moldable. The R&D team constantly plays with those ingredients to adjust smell and texture. A couple of times a day the team comes around with samples for employees to taste. That can sometimes hit a snag when they come around to Brown. The startup’s founder is a notoriously slow taste tester. “He’s been a vegan for so long that he doesn’t actually do a very good job,” Davis says. “He doesn’t know what meat tastes like.” Davis says the best description of the company’s first successful meat analog was rancid polenta. “It was still terrible,” he says. “And yet it was so much better than anything we’d made to that point.” The rule of the lab, explains Davis, is that, “it’s very bad manners to poison your friends, but you’re allowed to make it taste bad.” |

|

在食品行业,如果产品不成熟公司一般不会推出。但Impossible Foods 和Beyond Meat等公司在模仿科技行业,总在推出改进版本,用硅谷行话说就是“迭代”。 Impossible肉饼每次重大改版都用鸟类名字命名,蛇鸟、蓝脚布比鸟、秃鹰,还有渡渡鸟。不断的改进也代表了布朗的终极目标,即造出比牛还要美味的东西,而不只是像牛。布朗说,付出这么多努力不只是为了好吃的肉饼。“我们的使命就是食品生产环节中完全不用动物,”我们在纽约的高档餐厅Saxon + Parole里一边吃Impossible肉饼,他一边这么告诉我。公司内部叫这款肉饼黄鹂2.0版。 “不能毒死朋友,味道差点还能忍受。” Impossible Foods研发总监克里斯·戴维斯表示。 但事实上,公司技术方面还有个重要的决定方,就是美国食品药品管理局。虽然Impossible Foods不用申请便可在美国推广肉饼,但还是主动申请FDA确认其用来携带原血红素的蛋白质“通常比较安全”,简称GRAS。但FDA反馈了一些后续问题。(2015年,Impossible撤回了GRAS申请,去年10月增加一些安全数据后已重新提交。) 更让某些人担心的是,研究证明红肉中的原血红素会推动合成名叫N-亚硝基化合物的化学物质,或简称NOCs。该物质已证实有致癌作用。戴维斯并不相信。“现在有很多流行病学数据表明,吃肉不利于健康,”他表示, “看起来很清楚。但肉类哪一部分导致这种结果,数据里并没有显示。” 素食主义黑手党 对一些动物权益保护组织来说,替代肉类方面的努力也意味着帮他们在实现最终目标上取得了一些进展。保罗·夏皮罗在美国人道协会担任主管政策的副总裁,也是即将出版的《干净肉类》一书作者,他总结道:“从事该领域的人可能会真正保护到动物,比我努力一辈子还有成效。” 随着该领域获得进展,可能已经救了一些猪,也救了一些鸡,但用最重要的目标评判的话仍然失败:所谓最重要的目标,是让人们停止杀戮和食用动物。过去30年里,素食者的百分比基本保持不变。许多动物权益保护者提出,如果大部分美国人不会出于道德原因停止食用动物肉,也许应该提供更好的选择。 “我们应该注重研发各方面都更加创新的产品,而不是天天劝人们妥协。”凯尔·沃格特表示。 沃格特就是人们开玩笑时常说的素食黑手党之一,素食黑手党是一群富有的投资者,主要目标是避免动物成为食物。沃格特跟很多千禧一代一样,在Netflix上看过一系列类似题材的纪录片后开始对保护动物权益感兴趣。但跟很多同龄人不一样,2016年沃格特将无人驾驶汽车初创公司Cruise卖给了通用汽车,售价10亿美元,所以有钱投资。他和妻子特雷西·沃格特开设了一处农场动物庇护所,后来变成严格素食者,投资了Memphis Meats。对沃格特来说这是一次简单的思想实验:对100年后的人们来说,“哪些行为比较原始,令人讨厌,或完全错误?” |

In the food industry, companies traditionally don’t launch a product until they think it’s ready for prime time. But the likes of Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat are emulating the tech world by constantly rolling out improved versions—or in Valleyspeak, “iterations.” Every major reformulation of the Impossible Burger gets named after a bird—anhinga, blue-footed booby, condor, dodo. The updates represent Brown’s ultimate goal of making something superior to a cow rather than something identical to one. The effort is about far more than making a great burger, says Brown. “Our mission is to develop the technology that makes animals obsolete as a food production technology,” he tells me as we each chow down on an Impossible Burger—the version known internally as Oriole 2.0—at New York’s sleek Saxon + Parole restaurant. “It’s very bad manners to poison your friends, but you’re allowed to make it taste bad,” says Impossible Foods R&D Director Chris Davis. But as it turns out, there’s one rather important player who has some questions about the company’s technology. And that’s the FDA. While Impossible Foods doesn’t need the agency’s approval to market its burgers in the U.S., the company voluntarily asked the regulator to confirm the designation of the protein it uses to carry heme as something “generally recognized as safe,” or GRAS. But the FDA responded with some follow-up questions instead. (In November 2015, Impossible withdrew its GRAS submission but refiled this October with additional safety data.) More troubling to some is that studies have shown that heme found in red meat facilitates the production of chemicals called N-nitroso-compounds, or NOCs, that have been shown to be carcinogenic. Davis, for his part, is not convinced by the science. “Right now there’s good epidemiological data that eating meat is bad for you,” he says. “That’s pretty much clear. But which part of meat is causing that—the data just isn’t there.” The Vegan Mafia For some animal rights groups, the alt-meat effort marks a chance to finally make some progress on their ultimate aim. Or as Paul Shapiro, vice president of policy at the Humane Society of the United States and author of the forthcoming book Clean Meat, sums up: “It’s possible that folks in this field might end up doing more good for animals than what I’ve done with my life.” While the movement may have persuaded industry to free some pigs from gestation crates and hens from cages, it has so far pretty much failed in the goal many view as paramount: getting people to stop killing and consuming animals. The percentage of people who identify as vegetarians in the U.S. has remained essentially unchanged over the last three decades. If mainstream Americans won’t stop eating animal flesh for ethical reasons, suggest many animal rights advocates, then perhaps they will if they’re given a tastier alternative. “Rather than presenting people with tradeoffs, we should focus on making new products that are better than the status quo in every way,” says Kyle Vogt. Vogt is part of what several people jokingly refer to as the Vegan Mafia, a group of wealthy investors whose main motivation is to remove animals from the food system. Like a surprisingly large number of millennials, it seems, Vogt in part got interested in animal welfare after binge-watching a series of Netflix documentaries on the topic. But unlike many others in his age cohort, Vogt sold his self-driving-car startup Cruise to General Motors (GM, -0.27%) for $1 billion in 2016—and therefore has the money to do something about it. He and his wife, Tracy Vogt, who opened a farm animal sanctuary, subsequently became vegan and invested in Memphis Meats. For him it’s a straightforward thought experiment: For people living 100 years from now, “what are they going to see that seems barbaric or abhorrent or just completely wrong?” |

|

随着硅谷资本逐渐失去耐心,有些人开始议论。MosaMeat的珀斯特在2013年第一次用人工动物细胞制成汉堡,当时由谷歌亿万富翁布林支持。珀斯特认为有些竞争者计划进入市场的时间表不切实际,部分原因是为了迎合投资者。“整个硅谷的节奏都是迅速发展,”珀斯特告诉我。“可能不切实际,但硅谷的魅力和神话还有个特点,就是没人关心真相。” 行业的影响也能从公司选择语言中看出来,一些公司的描述中简单将生物描述为蛋白质转化技术。我写这篇报道的几个月里,经常听到类似描述。总是听起来很刺耳,而且有时候显得毫无灵魂。 “在大多数人类涉及的领域,技术是一件好事,”41岁的Modern Meadow联合创始人兼首席执行官安德拉斯·福佳科思说,该公司在新泽西州纳特利市的一个小校园里。“食物是人类存有怀疑的领域之一。”刚开始Modern Meadow就决定主要皮革材料,而不是肉类,因为公司认为皮革材料的影响更大。福佳科思还担心产品需要多长时间才能上市以及消费者能否接受。他解释说,所有食物都涉及技术,但是再有名的食品公司也不想提技术,他们想称之为烹饪艺术。不过,“如果想吸引投资者,而且产品看起来有创新性,就得用技术术语包装。”他表示,“对消费者来说不一定有吸引力。” 更显讽刺的是,替代肉行业真正获得信任是因为食品巨头加入。这一幕可谓峰回路转。之前传统包装食品公司吞并天然食品初创公司时,新生公司往往会销声匿迹。但这次肉类食品创新的情况相反:食品巨头在支持新生行业。 我跟泰森食品和嘉吉食品高管聊过,两家公司分别投资了Beyond Meat 和Memphis Meats,也许未来会出现动物肉、人工肉和植物肉在超市货架上并排摆着的一天。“为了养活90亿人,每个人都要贡献,”嘉吉食品成长型风投部门总裁索尼娅·麦卡隆姆·罗伯茨表示。“新行业对我们来说不是威胁,而是机会。” 但替代肉行业也不是所有人都想跟大佬们合作。Impossible首席执行官帕特·布朗就想不通,怎么可能找到跟传统肉类制造商相符的利益诉求。“这么说吧,”他表示。“我不敢想象,一旦那些公司能稍微掌控我们之后会发生什么。他们可不希望我们在未来15年颠覆传统行业。” 嘉吉食品的罗伯茨对此表示:“我听过一些类似说法。让人有点伤心。” 通过小测验 10月,300人左右在布鲁克林红钩一处改造过的仓库里聚会,此处正在举办第二届细胞农业新收获年度峰会。这种讨论替代肉的论坛上,午餐通常都是素食。(想找真正的牛奶加进咖啡?祝你好运。) 虽然行业太小,几乎人人都彼此认识,但也有不和谐的时候。尤其是很多初创公司鼓吹自家技术比同行先进时,明显引发了担心。受丑闻困扰的素食者,也是梅奥创始人汉普顿·克里克最近表示,明年人工肉产品就能面世,这番表态的真实性立刻引发争论。而且看来没有定论。(该公司在声明中称,“我们的目标是2018年底前推出第一款可量产的干净肉。”) 关于公司描述自家产品的方式,也能让人感觉到剑拔弩张的气息。对阵一方是享受古怪科技的乐趣(技术爱好者比较注重),另一方则是担心太古怪会吓跑消费者。 |

With Silicon Valley’s dollars has also come impatience, say some. Post, of MosaMeat, who created the first hamburger from cultured animal cells in 2013 with backing from Google billionaire Brin, believes some of his competitors have set unrealistic timelines to market in part because that’s what tech investors want to hear. “The whole Silicon Valley rhythm is imposed on this development,” Post tells me. “That may not be realistic, but part of the charm and myth of Silicon Valley is that nobody cares.” Its influence can also be seen in the language of the enterprise—one that casually refers to living creatures as protein conversion technologies. In the months I spent reporting this story, I heard those kinds of descriptions regularly. It was always jarring—and at times, came across as a bit soulless. “In most realms of human endeavor, technology is a positive thing,” says Andras Forgacs, the 41-year-old cofounder and CEO of Modern Meadow, which operates on a nondescript campus in Nutley, N.J. “Food is the one realm where we’re very suspicious about it.” Early on, Modern Meadow decided to focus on leather materials rather than meat because that’s where it thought it could have the most impact. Forgacs also had some concerns about how long it would take a food product to get to market as well as consumer acceptance. All food involves technology, he explains, but the most established food companies don’t want to call it that—they want to call it the art of cooking. Still, “if you want to attract investors and seem like you’re the revolutionary new thing, you have to robe yourself in the language of technology,” he says. “That doesn’t necessarily appeal to consumers.” In one of the stranger ironies, what has given real credence to the alt-meat realm is Big Food’s arrival on the scene. It’s an odd turn of events. When legacy packaged food companies began gobbling up natural food startups, the latter lost much of their street cred. But the opposite has happened with meat nouveau: Big Food’s backing has helped validate the burgeoning industry. The executives I spoke with at Tyson and Cargill, which have invested in Beyond Meat and Memphis Meats, respectively, laid out a future in which meat from animals, cultured meat, and plant-based meat all sit side by side in the supermarket. “To feed 9 billion people we’re going to need everybody,” says Sonya McCullum Roberts, president of growth ventures at Cargill. “It’s not a threat to us, it’s an opportunity.” Not everybody in the alt-meat crowd is willing to partner with the big guys. Pat Brown, Impossible’s CEO, can’t imagine how his interests could possibly align with those of a meat producer. “Let’s put it this way,” he says. “I don’t have any illusions about what would happen if one of those companies had any measure of control over us. They would not want us to completely replace their industry in 15 years.” Says Cargill’s Roberts: “I have heard some of those comments. And they hurt a little bit.” Passing the Smell Test In October some 300 people gather in a converted warehouse in Red Hook, Brooklyn, for the second annual New Harvest conference on cellular agriculture. As is typical of alt-meat confabs, the lunch is vegan. (And good luck finding any real milk for your coffee.) Despite the niceties that come in an industry where everyone knows everyone else, there are still plenty of moments of discord. One clear point of angst is how candid the various startups are being with one another about the advancements of their technology. Scandal-plagued vegan mayo maker Hampton Creek had recently said it would have a cultured meat product on the market next year, and questions abound about how realistic the pronouncement really is. Not very, seems to be the consensus. (“We aim to make our first commercial sale of a clean meat product by the end of 2018,” the company said in a statement.) One can sense another underlying tension in the way companies are describing their products in the first place. The battle lines seem drawn between the joys of weird science (which the techies cherish) and those who fear consumers will run from that. |

|

International Flavors and Fragrances的杰西·沃尔夫显然属于第一阵营。第二天会议刚开始,他就发表了“声味并茂”的演讲:他让大家打开每人座位上的小玻璃瓶,闻一下味道。他介绍说,瓶子里62种成分,组合起来会形成有机素食烤鸡香味。他告诉众人,制成香味需要很多科学。(我把小瓶带回办公室给同事们闻,大部分人都觉得像多力多滋玉米片。) 两小时后,一场名叫“推动细胞农业进入真实世界”的讨论环节中,芝加哥咨询公司Hyde Park Group食品创新负责人玛丽·哈德莱茵提到一种奇怪的现象,现在有几十种容易让人上瘾的添加剂,然而购物者都希望越简单越好。她对参会者说,少添加剂、未加工食物和干净的食品标签会很有发展前景。“另一方面我们又有了实验室出产的新型肉。应该好好关注各种矛盾的想法。” 关于细胞农业制出的肉应该叫什么名字也存在争议,凸显了该问题的复杂性。之前叫“实验室肉”、“试管肉”和“人工肉”,听起来都令人作呕,现在行业倾向于叫“干净肉”。但干净肉好像也不太合适。首先,消费者往往认为干净食品是没有人工添加剂的,这点就不太一样。“听起来像给生物工程制造的肉类产品取了个怪名字,”哈德莱茵告诉我。但更麻烦的在于,干净肉这个名字暗示普通的传统肉类肮脏,仿佛不该吃。“这个名字很有攻击性,而且毫不在意农民的感受,” Food + Tech Connect创始人兼首席执行官丹妮尔·古尔德表示,这家公司为食品行业创业者和投资人提供资源并打造社区。妖魔化潜在顾客,带着批判眼光且让其产生愧疚情绪,这种推广策略不太可能奏效。 “真正的问题是,他们是想养活人类,还是纯粹为了满足自我需求,”一位长期从事肉类行业的人问道。 素食肉支持者也难免遭遇矛盾。去年夏天,加州大学伯克利分校组建了替代肉类实验室,学生可以进行植物食品研究。项目非常受欢迎,后来扩大规模才能多容纳十几个人。但第一学期之后学生们很不满意,因为制成产品跟加工食品的配方一样复杂。新实验室联系主席理查多·圣马丁表示,学生们想改变当前的食品行业,而不是全盘复制。即便做植物肉饼,看起来也没太创新。“他们不相信未来想继续这么做,”圣马丁表示。“学生们觉得这样只是满足了保护动物的愿望,但在解决食物问题上作用不大。” 写这篇报道过程中,我几乎问所有人是不是素食者。我很吃惊地发现很多从事该行业的人并非素食者。MosaMeat的珀斯特说,他应该当素食者但并不是。“有些说不出的因素,让我们感觉很难跨出那一步,全面接受植物食品,”他承认。“感觉像后退一大步。我不太愿意。”替代肉实验室等等圣马丁表示,每次看到动物受虐待的消息都很难受,“但我走进超市吃汉堡时,跟之前看到的消息联系不到一起。就是做不到彻底不吃。” 我也能感觉到很多人的纠结。大多数时候我是素食者,基本上不吃红肉。在我写这篇报道的几个月里,对人们为何不该吃牛肉、鸡肉和猪肉的原因也加深了了解。 但11月初我在北加州高速公路上开车,看到前方有家速食汉堡连锁店。我抵不过内心纠结,停下车进去吃了个汉堡。那天的汉堡真是美味至极。(财富中文网) 本文另一版本发表于12月15日出版的《财富》杂志,标题是《牛肉都去哪了?》 译者:Pessy 审校:夏林 |

Jesse Wolff of International Flavors and Fragrances is clearly in the first camp. He kicks off day two with a presentation that includes show and smell: He instructs us to open a vial that’s been placed on the back of every chair, and then take a whiff. Inside are 62 components that make up organic vegan roast chicken aroma, he says. There’s a lot of science behind the flavor, he tells the crowd. (When I take the vial back to my office, most of my colleagues think it smells like Doritos.) Two hours later, during a session called “Getting Cellular Agriculture Into the Real World,” Mary Haderlein, principal of Chicago consulting firm Hyde Park Group Food Innovation, alludes to the strangeness of an additive with more than five dozen ingredients in an era when shoppers say they want simplicity. There’s a big push for fewer ingredients, unprocessed foods, and clean labels, she tells the same conference-goers. “And then on the other hand we have lab meat. Those are conflicting thoughts that have to come into focus.” Embodying this issue is the debate over what to even call meat made from cellular ag. The industry has landed on “clean meat,” after deciding that terms like “lab-grown meat,” “in vitro meat,” and “cultured meat” all have too much of an ick factor. But clean meat has its own baggage. For one thing, it has a different meaning to consumers who think of clean food as something free of artificial ingredients. “It seems like a weird term to attach to a bioengineered meat product,” Haderlein tells me. But even more problematic is that clean meat suggests that the alternative—plain, old regular meat—is dirty and wrong. “The term is offensive and insensitive to farmers,” says Danielle Gould, founder and CEO of Food + Tech Connect, a resource hub and community for food entrepreneurs and investors. And making potential consumers feel demonized, judged, or guilty is unlikely to be an effective marketing strategy. “The real question is, are they feeding people or are they feeding egos,” asks a meat industry veteran. The veggie meat cohort is not immune to the tension. This summer, the University of California at Berkeley launched an alt-meat lab for students to do plant-based food research. The program was so popular it was expanded to accommodate about a dozen extra people. But the students rebelled after the first semester, disheartened by how many of the products had the same heavy formulation as processed foods. They wanted to change the current food system, not replicate it, says Ricardo San Martin, cochair for the new lab. Somehow making a burger, even one made of plants, didn’t seem quite so innovative. “They were not convinced that this was the route they want to take,” San Martin says. “They feel it fulfills their ethical concerns with animals, but it doesn’t fulfill the kind of food they want to eat.” Over the course of reporting this story I asked pretty much everyone I talked to whether they were vegetarian or vegan. It was surprising to me how many of those engaged in this movement weren’t. Post, of MosaMeat, said that he should be but that he wasn’t. “There is something in us that makes it inherently difficult to take that step to a plant-based diet,” he admits. “It feels like a step back. And something in me resists that.” San Martin of the alt-meat lab offered that he feels horrible whenever he sees any information on the mistreatment of animals, “but when I go to the supermarket and eat ham, I don’t see the connection. I just can’t make it.” I felt their confusion. Most days I eat vegetarian, and I rarely eat any red meat at all. In fact, for months, as I’ve reported this story, I’ve been acutely aware of all the reasons why we probably shouldn’t eat beef, chicken, or pork. But in early November, as I was driving on the highway in Northern California, I saw an In-N-Out Burger up ahead. I pulled off the highway, and gave into the cognitive dissonance. It was the best hamburger I can remember. A version of this article appears in the Dec. 15, 2017 issue of Fortune with the headline “Where’s the Beef?” |