拉里·萨默斯谈抗通胀:美国加息远未到位,衰退仍然是大概率

今年8月,美国参议院里的民主党人正在为一场关键投票而努力,这场投票事关美国总统乔·拜登的一项重要国内施政方针——《通胀削减法案》(Inflation Reduction Act),如果得到通过,它就将为绿色能源和其他国内支出提供巨量投资。由于参议院的政治立场基本上势均力敌,所以民主党人还得说服一位重要人士,他就是西弗吉尼亚州民主党籍参议员乔·曼钦,他希望得到提案方的保证,即任何新支出法案都不会引发通胀。

民主党动用了一门重量级武器——他们没有求助于内阁成员,也没有去找任何知名的政界人士,而是找到了哈佛大学的经济学教授、美国财政部的前部长拉里·萨默斯。他自2010年以来就没有在政府中担任过任何正式职务了。弗吉尼亚州民主党籍参议员马克·沃纳回忆道:“当时我一边从地下通道里赶回哈特大厦,一边对还在巴西开会的萨默斯说:‘你必须给乔·曼钦打电话,你必须现在就打,而且你必须说服他这个法案是没有问题的。’”

几个星期后,萨默斯在布鲁克莱恩的家中接受《财富》杂志采访时证实,他确实打了那个电话——当然,有了曼钦的投票,这项法案也顺利得以通过。萨默斯不愿意透露过多细节,不过他表示:“我确实在后期参与了不少政治活动,我敢说这项法案不会引发通胀,几位参议员也鼓励我利用自己的信誉给这个法案背书,而我也确实这样做了。”

正因为他是研究通胀的大师,我们才会在夏末的一天亲自登门拜访他。萨默斯曾经担任美国前总统比尔·克林顿政府的财政部部长和前总统贝拉克·奥巴马的首席经济顾问。正因为见多识广,所以他从不害怕做大胆的预测,特别是最近他还发表了一项惊人的预言——他指出,美国政府在已经拿出巨额的抗疫支出和宽松货币政策后,又拟拿出1.9万亿美元的“美国拯救计划”(American Rescue Plan),这很可能会带来“一代人都未曾见过的通胀压力”。他愿意跟我们谈谈美国经济为何会陷入这种岌岌可危的状态,以及我们如何才可以摆脱这种状态。换句话说,他对当前的经济形势很不乐观。他警告道:“如果我们想要降低通胀,就需要比当前市场或者美联储所预期的更严格的政策。目前美联储还是太乐观了。”

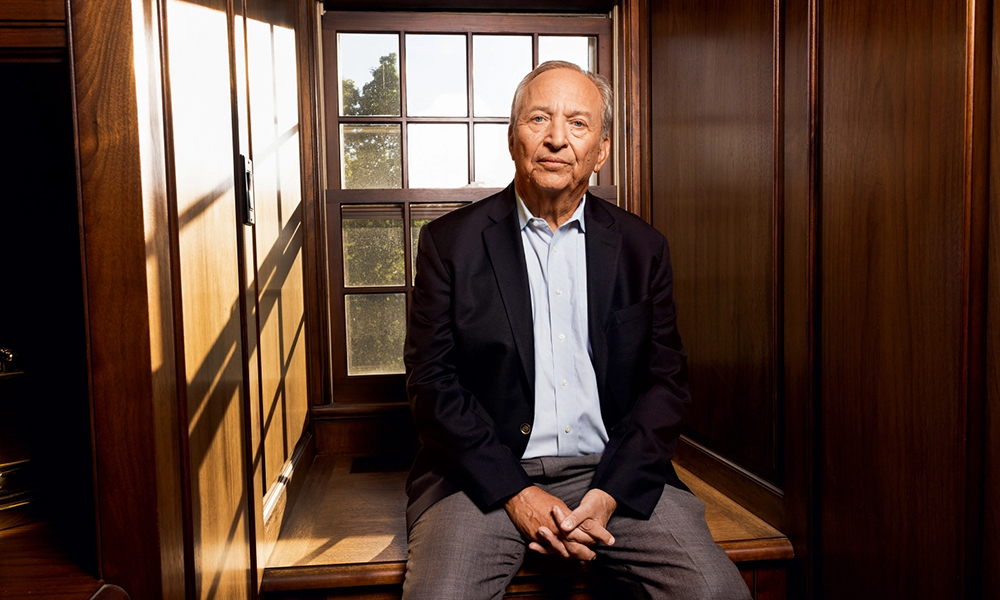

现在,这位著名经济学家每天都往返于哈佛大学和布鲁克莱恩之间。我们见面那天,他刚从科德角的避暑别墅回来。虽然坐拥哈佛大学的最高教职,但第二天他还要亲自上两堂政治经济学讲座,出席一场高级研讨会,总共要给400多个学生上课。他的黄色三层别墅坐落在一个山坡上的小区里,被掩映在一片有半个世纪树龄的美国梧桐中。这座房子的历史能够追溯到1901年,他在2006年卸任哈佛大学的校长一职后便一直居住在这里。房子的橡木地板上铺着东方风格的地毯,书架上陈列着他在政府任职期间的许多纪念品,其中包括一份手写的1999年参议院投票记录,当时参议院以97票赞成、2票反对的结果任命他为财政部部长。

《通胀削减法案》的通过让拜登获得了一场巨大的胜利,但它对萨默斯来说也是一场胜利。经过几十年的风风雨雨,萨默斯已经从一位杰出的经济学家,变成了美国政治经济界一位举足轻重的运筹帷幄者。该法案避免了抗疫期间的那种“大撒币”式的纾困支出——萨默斯对此是很反对的,而是支持对绿色能源进行长期投资,同时允许联邦医保(Medicare)开展处方药成本谈判,这两项政策的目的都是为了抑制通胀。另外,萨默斯还同意开放公共土地和水域开采油气,这也使他成了今年少数几位可以在对立政治阵营之间成功搭桥的人物。但另一方面,这种折衷的做法既没有取悦想要增加支出的激进派,也没有让想要减少支出的保守派满意。

不过由于当前的通胀仍然高得吓人——今年8月的美国通胀率达到了8.3%,因此两大阵营中认同萨默斯的观点,觉得形势很不乐观的人也越来越多。在萨默斯看来,目前最大的担忧,就是美国本来能够在接下来的几个月来个“长痛不如短痛”,但是美联储迄今尚未下定一步加息到位的决心,这可能导致最终解决方案所需付出的成本也要高得多。

在布鲁克莱恩的家中,萨默斯穿着灰色休闲裤、蓝色上衣和一双休闲鞋,打开了一罐原味可乐,开始侃侃而谈。

通胀是怎样一步步失控的

有一种论调称,美国当前的通胀是暂时性现象,是由于供应链瓶颈和防疫封控措施导致的。但萨默斯压根不认同这种看法。

在萨默斯看来,当今通胀严重的主要原因是需求被夸大了,是因为过多的货币追逐过少的商品导致的。因此,为了遏制不断上涨的消费者物价指数(CPI),美联储必须持续收紧货币政策,直至需求大幅下降。那么,萨默斯认为美联储还得在加息的路上走多远呢?

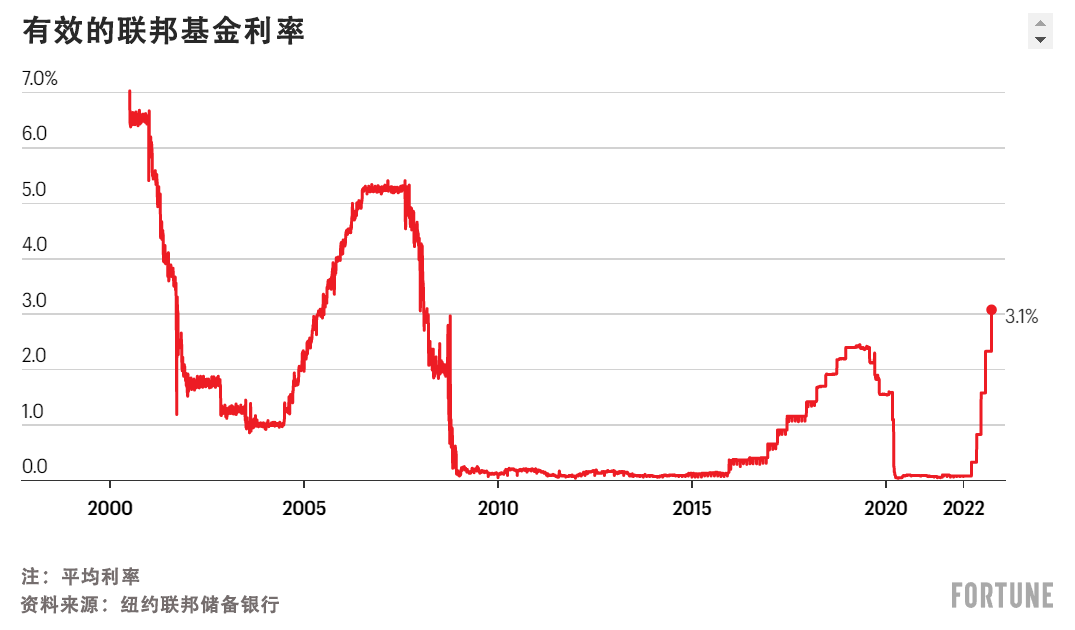

在萨默斯看来,经济学的核心是数学,这些问题的答案简直就是经济学的入门课程。据他估算,美国的“底层通胀”,也就是不包括食品和能源在内的通胀,大概是在4%到4.5%之间,与美联储拿来作参考的PCEPI指数非常接近。[PCEPI又称“个人消费支出价格指数”,由美国经济分析局(Bureau of Economic Analysis)计算,是一个被联邦政府广泛使用的指数,包括用于调整社保支出。]根据萨默斯的剧本,要抑制通胀,就需要一个“实际”的联邦基金利率,它要比基础通胀率高1.0%到1.5%。

根据萨默斯计算,这个实际利率的正确数字应该在5.0%到5.5%之间,这要远远高于当前联邦基金利率的中间值(3.1%)。当然,市场和大多数观察人士都预计,美联储还会在接下来几次会议上有大动作。但是调查显示,联邦基金期货市场和公开市场委员会(Open Market Committee)的成员普遍预计,这个数值明年最高也只能够达到4.6%左右。因此,萨默斯呼吁美联储进一步加大加息和紧缩力度,而且他呼吁的这个力度要比美联储和投资者的预期大得多。

房地产是一个对利率波动比较敏感的行业,最近的几轮加息已经给房市造成了很大冲击。美国企业研究所的住房中心的主任埃德·平托指出,如果基准利率达到5%或5.5%,“可能当我们达到这个数字时,经济已经陷入衰退了。”9月20日,美国的30年期抵押贷款利率已经达到6.4%,与一年前相比有了大幅上升,这已经使美国的住房销量比2021年同期低了三分之一,回落到了2015年的水平。据平托预计,从现在开始起一年内,美联储的大幅加息将美国房价平均下降8%到10%。

萨默斯认为,要使通胀率回落到美联储的2%的目标,就要抑制过度膨胀的需求。但收入的快速上涨正在削弱美联储的抗通胀努力。目前美国的个人收入增长率超过了5%,失业率在3.5%左右,达到了20世纪60年代末以来的最低的失业率水平。而只有当人们感到手头拮据,大幅减少了支出时,通胀压力才会缓解。萨默斯认为,经济现实决定了这种情况只会在失业率上升的时候发生,失业率一旦上升,每个空缺职位就会有更多人竞争。只有就业市场的热度冷下来,才会抑制工资的急剧上涨。

萨默斯指出:“现在每一个就业者背后,几乎都有两个空缺的招聘岗位。可以看出,目前的失业率处于十分罕见的水平。我不确定在失业率重回5%之前,你能否有效抑制通胀。而且你可能需要失业率一定时间内保持在6%。当然,我最希望的是这个计算出了错。”萨默斯最不希望看到老百姓的工作机会被毁掉。但他认为,只有短期内坚决遏制愈演愈烈的灾难性通胀,才能够确保未来的就业市场更加稳健发展。

萨默斯认为,目前美国陷入经济衰退的可能性为75%。他表示:“历史告诉我们,软着陆就代表着希望战胜了经验。而在通胀率高于4%且失业率低于4%的情况下,还没有经济能够实现软着陆的先例。因此如果经济不显著放缓,我们就不太可能达到美联储的抑制通胀目标。”

如果美联储按照萨默斯的剧本,采取坚定立场,美国需要多久才可以使通胀率回落到2%的目标?作为美国财政部前部长,萨默斯抨击了华尔街普遍存在的一种观点,即美联储能够迅速遏制通胀,然后在不久的将来再次开始放松政策。萨默斯称:“我认为这会需要好几年的时间,这一切都要取决于实体经济的情况,如果失业率上升到6%或7%,那么通胀回落的速度要比失业率在5%到5.5%时快得多。但有观点认为,美联储会在明年年中放松政策,而且这与我们让通胀率重回2%的路径一致。实际上,这种观点真的不太可能。”

亿万富翁、生物能源与下次疫情

当然,通货膨胀并不是目前萨默斯唯一关心的问题。我们在布鲁克莱恩采访时发现,他的想法简直是层出不穷,甚至在我们给他拍照的时候都谈兴甚浓。临走的时候,我忍不住还是问了这位大师对股价有什么看法。他说:“总的来看,股市似乎没有出现可能与严重衰退相关的那种利润下降,因此在我看来,股市还是很富裕的。而且我对股市的任何看法都是非常初步的。”他还引用了哈佛捐赠基金负责人、传奇投资者杰克·迈耶的故事:“在被问到他的成功秘诀时,他说他从不听信一个学经济学的。”

萨默斯认为,美国保持自由的创业文化是十分重要的,这种文化缔造了很多亿万富翁,但这些亿万富翁也创造了大量的就业机会。但同时这些亿万富翁的价值也被低估了。“如我们有更多像杰夫·贝佐斯、比尔·盖茨和史蒂夫·乔布斯这样既打造了庞大的企业,也赚到了巨额财富的人……那对美国就是有好处的。”同时萨默斯也支持“进行一系列税收改革,让他们交更多的税,同时防止这些大企业从商业帝国发展成代代相传的商业王朝。如果富人能够轻易将财富传给继承人,这就将是对机会均等的美国梦的侮辱。”

他还支持用水力压裂技术开采更多油气,以及增加油气管道取代危险的卡车运输。“最重要的是加快对能源和电力的运输审批流程。环保界对所有碳氢能源本能地一刀切地反对,这不仅对经济没有好处,也不符合他们自己的目标。”

从这一点上也可以看出,萨默斯对政府是不是应该干预、何时应该干预经济的问题上也有着自己的看法。“我一直认为,最好的将军是那些最不愿意发动战争,最不愿意将军事和暴力手段当成工具的人,他们虽然不好战,但是如果必要的时候也愿意战斗。”

他继续说道:“长期以来,我们一直在进行一场无结果的辩论,一方是在意识形态上反对任何扭曲完全自由市场政策的人,另一方则坚持政府必须要在商品和服务生产中发挥作用。而我们真正需要的,就是政府扮演一个‘避战而能战’的角色,以促进特定行业和政策。”

萨默斯还建议,联邦政府应该制定一个类似“马歇尔计划”的计划,以应对下一次疫情——他认为最多10年到15年,我们就会迎来下一次疫情。“疫情风险与气候风险在同一个量级上,但它没有得到应有的重视。相比于疫情造成的几十万亿美元的损失,我们如果在这上面花上一些钱,就可以在下次疫情时更加从容地应对。”萨默斯希望联邦政府设立一个疫情应对项目,资助疫苗厂商建造工厂,尽管这些工厂可能闲置很多年。同时要建立“快速生产疫苗的科研能力”,并且大量囤积口罩、注射器和其他设备,并且研发相关筛查设施。

在个人爱好上,萨默斯表示,他经常去布鲁克莱恩的乡村俱乐部打高尔夫球。尽管技术并不高明,但他打趣道:“我在高尔夫球场上唯一擅长的就是做概率分析,看是在小溪上方还是在小溪周围击球更好。可惜我不太擅长挥杆,而这项技能在球场上更重要。”另外他还会打网球,小时候他经常练习对墙打网球,所以练就了不错的击球技能。“在经过年龄和体能调整后,我其实是一个很好的网球运动员,如果从绝对的年龄调整来看,我真的是还不错的。”

当然,萨默斯还有一个任何经济学家都避免不了的爱好——为未来担忧。他批评了美国政府数万亿美元的抗疫纾困支出。他认为,这笔钱“可能会限制为抗击长期经济停滞所能调配的公共资源。我们就好比一个宁可借钱度假,也不愿意修缮屋顶或者扩建房子的家庭。我们借了这么多钱,但是我们只记得开派对。”所有这些鲁莽行为的后果,就是萨默斯预见到的大通胀。现在他又给出了另一个警告,而我们都要明白,要修复这个问题,我们需要付出多少牺牲。(财富中文网)

译者:朴成奎

今年8月,美国参议院里的民主党人正在为一场关键投票而努力,这场投票事关美国总统乔·拜登的一项重要国内施政方针——《通胀削减法案》(Inflation Reduction Act),如果得到通过,它就将为绿色能源和其他国内支出提供巨量投资。由于参议院的政治立场基本上势均力敌,所以民主党人还得说服一位重要人士,他就是西弗吉尼亚州民主党籍参议员乔·曼钦,他希望得到提案方的保证,即任何新支出法案都不会引发通胀。

民主党动用了一门重量级武器——他们没有求助于内阁成员,也没有去找任何知名的政界人士,而是找到了哈佛大学的经济学教授、美国财政部的前部长拉里·萨默斯。他自2010年以来就没有在政府中担任过任何正式职务了。弗吉尼亚州民主党籍参议员马克·沃纳回忆道:“当时我一边从地下通道里赶回哈特大厦,一边对还在巴西开会的萨默斯说:‘你必须给乔·曼钦打电话,你必须现在就打,而且你必须说服他这个法案是没有问题的。’”

几个星期后,萨默斯在布鲁克莱恩的家中接受《财富》杂志采访时证实,他确实打了那个电话——当然,有了曼钦的投票,这项法案也顺利得以通过。萨默斯不愿意透露过多细节,不过他表示:“我确实在后期参与了不少政治活动,我敢说这项法案不会引发通胀,几位参议员也鼓励我利用自己的信誉给这个法案背书,而我也确实这样做了。”

正因为他是研究通胀的大师,我们才会在夏末的一天亲自登门拜访他。萨默斯曾经担任美国前总统比尔·克林顿政府的财政部部长和前总统贝拉克·奥巴马的首席经济顾问。正因为见多识广,所以他从不害怕做大胆的预测,特别是最近他还发表了一项惊人的预言——他指出,美国政府在已经拿出巨额的抗疫支出和宽松货币政策后,又拟拿出1.9万亿美元的“美国拯救计划”(American Rescue Plan),这很可能会带来“一代人都未曾见过的通胀压力”。他愿意跟我们谈谈美国经济为何会陷入这种岌岌可危的状态,以及我们如何才可以摆脱这种状态。换句话说,他对当前的经济形势很不乐观。他警告道:“如果我们想要降低通胀,就需要比当前市场或者美联储所预期的更严格的政策。目前美联储还是太乐观了。”

现在,这位著名经济学家每天都往返于哈佛大学和布鲁克莱恩之间。我们见面那天,他刚从科德角的避暑别墅回来。虽然坐拥哈佛大学的最高教职,但第二天他还要亲自上两堂政治经济学讲座,出席一场高级研讨会,总共要给400多个学生上课。他的黄色三层别墅坐落在一个山坡上的小区里,被掩映在一片有半个世纪树龄的美国梧桐中。这座房子的历史能够追溯到1901年,他在2006年卸任哈佛大学的校长一职后便一直居住在这里。房子的橡木地板上铺着东方风格的地毯,书架上陈列着他在政府任职期间的许多纪念品,其中包括一份手写的1999年参议院投票记录,当时参议院以97票赞成、2票反对的结果任命他为财政部部长。

《通胀削减法案》的通过让拜登获得了一场巨大的胜利,但它对萨默斯来说也是一场胜利。经过几十年的风风雨雨,萨默斯已经从一位杰出的经济学家,变成了美国政治经济界一位举足轻重的运筹帷幄者。该法案避免了抗疫期间的那种“大撒币”式的纾困支出——萨默斯对此是很反对的,而是支持对绿色能源进行长期投资,同时允许联邦医保(Medicare)开展处方药成本谈判,这两项政策的目的都是为了抑制通胀。另外,萨默斯还同意开放公共土地和水域开采油气,这也使他成了今年少数几位可以在对立政治阵营之间成功搭桥的人物。但另一方面,这种折衷的做法既没有取悦想要增加支出的激进派,也没有让想要减少支出的保守派满意。

不过由于当前的通胀仍然高得吓人——今年8月的美国通胀率达到了8.3%,因此两大阵营中认同萨默斯的观点,觉得形势很不乐观的人也越来越多。在萨默斯看来,目前最大的担忧,就是美国本来能够在接下来的几个月来个“长痛不如短痛”,但是美联储迄今尚未下定一步加息到位的决心,这可能导致最终解决方案所需付出的成本也要高得多。

在布鲁克莱恩的家中,萨默斯穿着灰色休闲裤、蓝色上衣和一双休闲鞋,打开了一罐原味可乐,开始侃侃而谈。

通胀是怎样一步步失控的

有一种论调称,美国当前的通胀是暂时性现象,是由于供应链瓶颈和防疫封控措施导致的。但萨默斯压根不认同这种看法。

在萨默斯看来,当今通胀严重的主要原因是需求被夸大了,是因为过多的货币追逐过少的商品导致的。因此,为了遏制不断上涨的消费者物价指数(CPI),美联储必须持续收紧货币政策,直至需求大幅下降。那么,萨默斯认为美联储还得在加息的路上走多远呢?

在萨默斯看来,经济学的核心是数学,这些问题的答案简直就是经济学的入门课程。据他估算,美国的“底层通胀”,也就是不包括食品和能源在内的通胀,大概是在4%到4.5%之间,与美联储拿来作参考的PCEPI指数非常接近。[PCEPI又称“个人消费支出价格指数”,由美国经济分析局(Bureau of Economic Analysis)计算,是一个被联邦政府广泛使用的指数,包括用于调整社保支出。]根据萨默斯的剧本,要抑制通胀,就需要一个“实际”的联邦基金利率,它要比基础通胀率高1.0%到1.5%。

根据萨默斯计算,这个实际利率的正确数字应该在5.0%到5.5%之间,这要远远高于当前联邦基金利率的中间值(3.1%)。当然,市场和大多数观察人士都预计,美联储还会在接下来几次会议上有大动作。但是调查显示,联邦基金期货市场和公开市场委员会(Open Market Committee)的成员普遍预计,这个数值明年最高也只能够达到4.6%左右。因此,萨默斯呼吁美联储进一步加大加息和紧缩力度,而且他呼吁的这个力度要比美联储和投资者的预期大得多。

房地产是一个对利率波动比较敏感的行业,最近的几轮加息已经给房市造成了很大冲击。美国企业研究所的住房中心的主任埃德·平托指出,如果基准利率达到5%或5.5%,“可能当我们达到这个数字时,经济已经陷入衰退了。”9月20日,美国的30年期抵押贷款利率已经达到6.4%,与一年前相比有了大幅上升,这已经使美国的住房销量比2021年同期低了三分之一,回落到了2015年的水平。据平托预计,从现在开始起一年内,美联储的大幅加息将美国房价平均下降8%到10%。

萨默斯认为,要使通胀率回落到美联储的2%的目标,就要抑制过度膨胀的需求。但收入的快速上涨正在削弱美联储的抗通胀努力。目前美国的个人收入增长率超过了5%,失业率在3.5%左右,达到了20世纪60年代末以来的最低的失业率水平。而只有当人们感到手头拮据,大幅减少了支出时,通胀压力才会缓解。萨默斯认为,经济现实决定了这种情况只会在失业率上升的时候发生,失业率一旦上升,每个空缺职位就会有更多人竞争。只有就业市场的热度冷下来,才会抑制工资的急剧上涨。

萨默斯指出:“现在每一个就业者背后,几乎都有两个空缺的招聘岗位。可以看出,目前的失业率处于十分罕见的水平。我不确定在失业率重回5%之前,你能否有效抑制通胀。而且你可能需要失业率一定时间内保持在6%。当然,我最希望的是这个计算出了错。”萨默斯最不希望看到老百姓的工作机会被毁掉。但他认为,只有短期内坚决遏制愈演愈烈的灾难性通胀,才能够确保未来的就业市场更加稳健发展。

萨默斯认为,目前美国陷入经济衰退的可能性为75%。他表示:“历史告诉我们,软着陆就代表着希望战胜了经验。而在通胀率高于4%且失业率低于4%的情况下,还没有经济能够实现软着陆的先例。因此如果经济不显著放缓,我们就不太可能达到美联储的抑制通胀目标。”

如果美联储按照萨默斯的剧本,采取坚定立场,美国需要多久才可以使通胀率回落到2%的目标?作为美国财政部前部长,萨默斯抨击了华尔街普遍存在的一种观点,即美联储能够迅速遏制通胀,然后在不久的将来再次开始放松政策。萨默斯称:“我认为这会需要好几年的时间,这一切都要取决于实体经济的情况,如果失业率上升到6%或7%,那么通胀回落的速度要比失业率在5%到5.5%时快得多。但有观点认为,美联储会在明年年中放松政策,而且这与我们让通胀率重回2%的路径一致。实际上,这种观点真的不太可能。”

亿万富翁、生物能源与下次疫情

当然,通货膨胀并不是目前萨默斯唯一关心的问题。我们在布鲁克莱恩采访时发现,他的想法简直是层出不穷,甚至在我们给他拍照的时候都谈兴甚浓。临走的时候,我忍不住还是问了这位大师对股价有什么看法。他说:“总的来看,股市似乎没有出现可能与严重衰退相关的那种利润下降,因此在我看来,股市还是很富裕的。而且我对股市的任何看法都是非常初步的。”他还引用了哈佛捐赠基金负责人、传奇投资者杰克·迈耶的故事:“在被问到他的成功秘诀时,他说他从不听信一个学经济学的。”

萨默斯认为,美国保持自由的创业文化是十分重要的,这种文化缔造了很多亿万富翁,但这些亿万富翁也创造了大量的就业机会。但同时这些亿万富翁的价值也被低估了。“如我们有更多像杰夫·贝佐斯、比尔·盖茨和史蒂夫·乔布斯这样既打造了庞大的企业,也赚到了巨额财富的人……那对美国就是有好处的。”同时萨默斯也支持“进行一系列税收改革,让他们交更多的税,同时防止这些大企业从商业帝国发展成代代相传的商业王朝。如果富人能够轻易将财富传给继承人,这就将是对机会均等的美国梦的侮辱。”

他还支持用水力压裂技术开采更多油气,以及增加油气管道取代危险的卡车运输。“最重要的是加快对能源和电力的运输审批流程。环保界对所有碳氢能源本能地一刀切地反对,这不仅对经济没有好处,也不符合他们自己的目标。”

从这一点上也可以看出,萨默斯对政府是不是应该干预、何时应该干预经济的问题上也有着自己的看法。“我一直认为,最好的将军是那些最不愿意发动战争,最不愿意将军事和暴力手段当成工具的人,他们虽然不好战,但是如果必要的时候也愿意战斗。”

他继续说道:“长期以来,我们一直在进行一场无结果的辩论,一方是在意识形态上反对任何扭曲完全自由市场政策的人,另一方则坚持政府必须要在商品和服务生产中发挥作用。而我们真正需要的,就是政府扮演一个‘避战而能战’的角色,以促进特定行业和政策。”

萨默斯还建议,联邦政府应该制定一个类似“马歇尔计划”的计划,以应对下一次疫情——他认为最多10年到15年,我们就会迎来下一次疫情。“疫情风险与气候风险在同一个量级上,但它没有得到应有的重视。相比于疫情造成的几十万亿美元的损失,我们如果在这上面花上一些钱,就可以在下次疫情时更加从容地应对。”萨默斯希望联邦政府设立一个疫情应对项目,资助疫苗厂商建造工厂,尽管这些工厂可能闲置很多年。同时要建立“快速生产疫苗的科研能力”,并且大量囤积口罩、注射器和其他设备,并且研发相关筛查设施。

在个人爱好上,萨默斯表示,他经常去布鲁克莱恩的乡村俱乐部打高尔夫球。尽管技术并不高明,但他打趣道:“我在高尔夫球场上唯一擅长的就是做概率分析,看是在小溪上方还是在小溪周围击球更好。可惜我不太擅长挥杆,而这项技能在球场上更重要。”另外他还会打网球,小时候他经常练习对墙打网球,所以练就了不错的击球技能。“在经过年龄和体能调整后,我其实是一个很好的网球运动员,如果从绝对的年龄调整来看,我真的是还不错的。”

当然,萨默斯还有一个任何经济学家都避免不了的爱好——为未来担忧。他批评了美国政府数万亿美元的抗疫纾困支出。他认为,这笔钱“可能会限制为抗击长期经济停滞所能调配的公共资源。我们就好比一个宁可借钱度假,也不愿意修缮屋顶或者扩建房子的家庭。我们借了这么多钱,但是我们只记得开派对。”所有这些鲁莽行为的后果,就是萨默斯预见到的大通胀。现在他又给出了另一个警告,而我们都要明白,要修复这个问题,我们需要付出多少牺牲。(财富中文网)

译者:朴成奎

Senate Democrats were careening toward a pivotal vote this August—one that could either resuscitate President Biden’s domestic agenda, or pull the plug on it. They wanted to pass the Inflation Reduction Act, a huge bill that would fund dramatic green energy investments and other domestic spending. The Dems needed to flip one senator to squeeze the legislation through the evenly divided chamber—that of their own colleague, Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.), who wanted assurances that any new spending bill wouldn’t be inflationary.

The Dems called in the heavy artillery—but they didn’t turn to a cabinet member, or a big-name lobbyist, or any current political headliner. They called on Larry Summers, the rumpled, cerebral Harvard economics professor and former Treasury secretary who hasn’t held a formal role in government since 2010. Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.) recalled the frenetic home stretch in a press report: “I was walking the tunnels back to the Hart Building and saying to Larry, who was at some conference in Brazil at the time, ‘You gotta call Joe Manchin, and you gotta do it right now and convince him this is all cool.’”

A few weeks later, visiting with Fortune in his living room in tony Brookline, Summers confirms it: He placed the call. (The bill passed, of course, with Manchin’s vote.) Summers won’t go into specifics, but says, “I was quite involved in the politics in the late stages.” He adds: “I had credibility to say that [this bill] would not be inflationary. Several senators encouraged me to deploy that credibility, and I did.”

That credibility is the reason we’re talking in his parlor on a late summer day. Larry Summers has never been one to shy away from bold predictions, and recently he has stood out for one particular pronouncement. Summers—Treasury secretary under Bill Clinton, and chief economic adviser to Barack Obama—strenuously warned that the proposed $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, following already gigantic COVID relief spending and loose monetary policy, could “set off inflationary pressures … unseen for a generation.” He’s agreed to meet with us to discuss how the economy got into its current shaky state—and how we might get out of it. He is, to say the least, not very upbeat. “If we’re going to bring down inflation, you likely need a policy more restrictive than the policy that’s contemplated by the markets or the Fed,” he warns. “The Fed continues to be excessively optimistic.”

Today, the noted economist commutes from Brookline to Harvard, where he holds the highest faculty rank, as university professor. When we met, he’d just returned from his summer house in Cape Cod; the next day, he would teach more than 400 students, at two political economics lectures and an advanced seminar. His yellow, columned three-story house, in a hilly neighborhood shaded by half-century-old sycamores, dates from 1901—he’s lived here since leaving the Harvard presidency in 2006. Oriental rugs cover the oak floors, and the shelves feature a number of trophies from his time in government—including a handwritten record of the Senate roll call from 1999 that confirmed him as Treasury secretary by a vote of 97 to two.

The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act gave Biden a huge win. But it was a win for Summers, too, who has risen over the decades from a brilliant economist (if prone to foot-in-mouth moments) to an éminence grise in the economic and political realms. The bill eschewed the COVID-style stimulus checks Summers railed against in favor of longer-term investments in green energy and a provision that allows Medicare to negotiate prescription drug costs, both aimed at lowering inflation. With nods toward opening up public lands and waters to drilling and fracking, it also solidified Summers’ status as a rare public figure in 2022 who is able to build bridges between opposing camps. On the flip side, this meet-in-the-middle approach manages to please neither progressives who want more spending nor conservatives who want less.

Still, as inflation remains worryingly high—clocking in at 8.3% in the latest August reading—a growing number of people in both camps now share Summers’ view that things are not, exactly, cool. For Summers, the greatest worry is that the Fed won’t have the resolve to raise rates high enough, and that the eventual cure will be far more costly than shouldering what could be a shorter, shallower downturn in the months ahead.

Back in Brookline, Summers—wearing gray slacks, a blue blazer and loafers sans visible socks—cracks open a can of Coke Original and starts talking.

How inflation spiraled out of control

Summers never bought the “transitory” argument, that inflation was a passing phenomenon caused by supply-chain bottlenecks and COVID-related shutdowns.

For Summers, the chief source of today’s heavy inflation is over-the-top demand caused by too much money chasing too few goods. So to throttle a runaway consumer price index, the Fed must keep tightening monetary policy to the point where demand falls—sharply. Just how far does Summers think the Fed needs to go?

Getting to the answers is a primer in Summers’ view that the heart of economics is arithmetic. He reckons that “underlying inflation,” excluding food and energy, is running at 4% to 4.5%, pretty close to the PCEPI (personal consumption expenditure price index) numbers that guide the Fed. (The PCEPI is calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis and widely used by the federal government, including to adjust Social Security payments.) In the Summers playbook, taming inflation requires a “real,” Fed funds rate that’s 1.0% to 1.5% higher than the pace of bedrock inflation.

By his reckoning, the right number is 5.0% to 5.5%. That’s far above the current Fed funds benchmark which is at a midpoint of 3.1%. Of course, the markets and most observers expect the Fed to go big again at the next several meetings. But the Fed funds futures markets, and the members of the Open Market Committee in their most recent poll, expect the number to max out at 4.6% next year. So Summers is calling for much higher Fed funds rate, and tighter policies, than investors or the Fed itself are anticipating.

Rising rates are already pummeling the giant industry most influenced by their fluctuations: housing. According to Ed Pinto, director of the American Enterprise Institute’s Housing Center, at 5% or 5.5%, “it’s likely that by the time we’d get to that number, the economy would already be in recession.” 30-year mortgage rates clocked in at 6.4% on Sept. 20—a collossal jump from just a year ago, and one that has already pushed home sales volumes one-third below 2021 numbers to where they stood in 2015. Pinto projects that by a year from now, the campaign of rates hikes will have pushed home values down an average of 8-10% across the board.

Wrestling inflation to near the Fed’s 2% target, Summers reckons, means crushing overblown demand. But fast-rising incomes are blunting the Fed’s campaign to fight inflation. Personal incomes are growing at over 5%, driven by a jobless rate in the mid-3% range that’s the lowest since the late 1960s. Inflationary pressures will only ease when Americans are feeling the pinch, when they’re spending a lot less money. Summers believes that economic reality dictates that will only happen when joblessness rises, so that more workers are available for each open job. Creating slack in the super-cramped labor market would curb the steep rise in wages.

“We’re seeing two vacancies for every employed person,” says Summers. “That number and the unemployment rate are at extraordinary levels. I’m not sure you’re restraining inflation until you get the unemployment rate close to 5%, and to significantly restrain inflation you’re likely to need unemployment for some period at 6%. I’d like nothing better than to be wrong in that calculation.” Job destruction is the last thing Summers wants to see. But he thinks that a tough campaign to contain the outbreak that costs jobs in the short run will ensure a much stronger job market in the future than the catastrophic choice of allowing inflation to keep bubbling.

Summers puts the chance of a recession at 75%. “History teaches us that soft landings represent the triumph of hope over experience,” he says. “There are no examples when inflation was above 4% and unemployment was below 4% that the economy achieved a soft landing. We are unlikely to achieve a reduction of inflation to something like the Fed’s target without a significant slowing of the economy.”

How long will it take for the Fed to push inflation back to the 2% goal, providing the central bank maintains the resolute stance Summers recommends? Here, the former Treasury secretary punctures the idea widespread on Wall Street that the central bank can quickly corral inflation, then start easing again in the not-too-distant future. “I suspect [it will take] several years,” he says. “It all depends on what happens in the real economy. If unemployment spikes to 6% or 7%, it will happen more quickly than if it stays at 5% or 5.5%. But the view that the Fed will be in a position to start easing in the middle of next year, and that that is consistent with the path to get us back to 2% inflation, really seems to me quite unlikely.”

Billionaires, biofuels, and the next pandemic

Of course inflation is hardly the only thing on Summers’ mind these days. During our interview in Brookline he was brimming with so many ideas that he wanted to keep talking during a picture-taking session in his top-floor study, a kind of book-lined, paneled aerie overlooking the rolling hills and cupolas of the surrounding suburb. I couldn’t leave without asking the great sage what he thought of today’s stock prices. “In general, it seems that the stock market is not pricing in the kind of decline in profits that would be associated with a meaningful recession, and therefore has looked rich to me,” he noted. “I hold any opinion on the level of the stock market very tentatively.” And he cited Jack Meyer, the legendary investor who headed Harvard’s endowment, “who, when asked the secret of his success, said that he never listened to a member of the economics department.”

Broadly speaking he thinks it’s crucial for America to keep the freewheeling entrepreneurial culture that spawns so many mega-billionaires because they’re also mega-job-creators. But he also believes they’re under-taxed: “If we had more people like Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates and Steve Jobs who built spectacular enterprises and made inordinate fortunes … that would be good for America.” But he also favors “a whole set of tax changes that would make them pay more and complicate any efforts to form intergenerational dynasties. The ease with which the wealthy can pass on their wealth to their heirs is an affront to the American ideal of equal opportunity.”

He also supports more fracking and adding pipelines to replace the dangerous shipping of oil and gas on trucks: “What is most important is accelerating approvals for transmission and of both fuels and electricity. Reflex opposition to anything involving hydrocarbons in the environmental community is counterproductive, not only to the economy but to their own objectives.”

This plays into his nuanced view about when and how much governments should intervene in capitalism: “I’ve always believed the best generals are the ones that are most troubled by war and most skeptical about the military and violence as a tool. They’re reluctant warriors, but willing to fight if necessary.”

He adds: “For too long, we’ve had a sterile debate between those who ideologically oppose any policies that distort the perfectly free market and the Curtis LeMays of industrial policy who rush to seize on any argument for the government to take a role in the production of goods and services. What we need is a reluctant warrior approach on policies that promote specific industries and policies.”

Summers is furthermore championing a kind of federal Marshall Plan for countering the next pandemic, which he sees arriving within 10 to 15 years: “The pandemic risk is on the same order of magnitude as climate risk, but it’s not getting nearly the level of attention that it should,” he told me. “For pittances of tens of billions of dollars, relative to the tens of trillions that COVID has cost, we could be in a better position to act next time.” Summers wants a federal program that pays vaccine makers to build plants prepared for an outbreak that could sit idle for years; supports “scientific capacity to make vaccines quickly”; amasses big stockpiles of masks, syringes, and other equipment; and develops an infrastructure for screening.

As for his hobbies, Summers says he’s a frequent golfer at the Country Club in Brookline. Though he sports a 19 handicap, he quips: “The only aspect of the golf game I’m good at is doing a probabilistic analysis of whether it’s better to shoot over the creek or around the creek. Unfortunately, I’m not very good at swinging a golf club, which is a rather more important skill.” As for tennis, hours spent pounding balls against a backboard as a kid forged the reliable baseline game that he marshals at the famed Longwood Cricket Club. “On a physique and age-adjusted basis, I’m actually a very good tennis player, based on those reliable groundstrokes,” he declares. “On an absolute age-adjusted basis, I’m not bad.”

And of course, there’s one hobby that no economist can fully give up: worrying about the future. Summers frets that the legacy from the trillions in COVID relief spending he was so foresighted in criticizing, “may limit the resources available for the public investment needed for fighting secular stagnation. We’re like a family that borrowed a lot for its vacation rather than to fix its roof or expand its house. We have our debt and only memories of the party we had.” The aftermath of all that recklessness is the big inflation that Summers presciently saw coming. Now he’s making another contrarian call we should all heed on the sacrifices needed to fix it.