小米在印度,还能火多久?

自六年前,中国智能手机制造商小米正式进入印度市场时,就借助印度最大的宗教节日排灯节(Diwali)进行广告宣传,宣传语:“Diwali with Mi”——Mi是Xiaomi的简称。这些广告将小米与这一节日紧密结合在一起,印度人对其的期待不亚于圣诞节来临时,美国人对可口可乐北极熊广告的期待。

今年的宣传活动是将流行文化与小米的最高管理层相结合——印度首位著名的印地语说唱歌手巴巴•塞加尔,以及39岁小米全球副总裁兼印度总经理马努•库马尔•贾因一同参与制作了几段广告视频。视频里,在朗朗上口的迭句副歌“Diwali with Mi”中,两人互相调侃,谁才是更好的说唱歌手。

贾因笑着告诉《财富》杂志,这些视频“有点让人尴尬”,但它们似乎引起了印度消费者的共鸣。在系列广告视频中,最受欢迎的一段在YouTube的点击率达到了600余万次。在长达一个月的促销期间,小米卖出了900万台智能手机。

在印度,小米一个季度的手机销量一般只有1200万台,所以贾因认为,小米在排灯节(截至11月14日)的促销很成功。

这家来自北京的《财富》世界500强公司今年才刚满10岁,但其排灯节广告已经使这家公司在印度拥有了很强的影响力。小米已在印度建厂,开了几千家零售店,并努力研发印度人喜欢的手机和设备,甚至包括智能净水器。

还有像它一样成功的品牌吗?其他外国手机品牌在印度几乎已无立锥之地。

印度索波雷小米广告牌。图片来源:纳西尔•卡奇鲁——/盖蒂图片社

印度索波雷小米广告牌。图片来源:纳西尔•卡奇鲁——/盖蒂图片社印度是全球增长最快的手机市场,每天有超过30万新人加入智能手机用户群,小米连续3年成为印度最畅销的手机品牌。

2020年至今,小米已经在印度销售手机2900万台,比中国还要多200万台,在印度占有四分之一的智能手机市场。

十年前小米创建时,科技媒体称它是“中国的苹果”,因为小米手机的外观时尚、价格实惠,迎合了中国不断壮大的年轻中产阶级的需求。小米趁势大肆宣传,现已上市,成为2016年全球最具价值的私人初创公司。但这惹恼了库比蒂诺的设计师们,他们嘲笑小米手机是iPhone的廉价追随者。

到今天,小米已然成为名副其实的手机巨头,去年营收300亿美元,市值达784亿美元。据摩根士丹利统计,小米印度营收占小米总营收的20%,小米品牌已经走出苹果阴影。2020年第三季度,小米全球手机出货量冲到第三位,首次超越苹果,排名第四。

国际数据公司(IDC)科技分析师纳夫肯达尔•辛格感叹说,小米最近在印度节节高升,但它的确遇到了很强的阻力。

今年6月,中印边境爆发冲突后,印度发起了抵制中国产品运动。这也意味着,小米在印度的发展之路可能取决于小米在印度的根基是否足以证明该品牌具有足够的印度特色。

2014年,小米带着旗舰手机Mi 3闯入印度,与其它手机相比,Mi 3拥有更快的处理器、更好的摄像头、更大的内存容量,定价却只有约200美元。

辛格说,小米手机支持4G,而三星、微软、印度品牌Micromax还停留在3G。

进入印度市场标志着小米首次在国际市场大规模扩张,它在印度次大陆推行相同的“限时特卖”策略,4年之后便成为印度第一大手机制造商。(后来,这一头衔被价格更便宜的竞争对手华为夺去。)只在网上限量销售产品,致使消费者狂热追捧,避免了生产过剩成本;不开设实体店,也就节省了管理费用。

小米与印度电商创业公司Flipkart合作,作为印度的旗舰科技巨头之一的Flipkart成为了小米手机的独家经销商。

2014年7月,第一批约1万台Mi 3智能手机只用了不到半小时就销售一空。Flipkart称,就在同一个月月末,小米Mi 3再次促销,5秒售罄;8月时第三次促销,2秒售罄。

2015年,风云突变,印度政府突然将智能手机进口关税增加一倍,达到12.5%,因为印度要推行“印度制造”战略。

当时小米的供应链几乎全部放在中国,在关税压力下,小米被迫调高印度手机售价,竞争力大幅削弱。为了寻求突破,小米与富士康于2015年首次合作,在印度设立制造基地。

印度新工厂生产的小米手机属于“印度制造”,可以避开关税。有了低价作保障,小米手机在印度的市场份额迅速攀升,2015年只有3.3%,2016年猛增到13.3%。

晨星(Morningstar)资深股票分析师丹•贝克说,小米抢在中国对手之前在国外开拓市场,他还说:“从销量看,中国市场暂时处于倒退状态,但印度仍处于增长态势,所以他们在正确的时间,瞄准了正确的市场。”

小米比苹果提前五年将供应链转移到印度,而苹果去年才开始通过富士康在印度制造iPhone。

在印度开设实体店方面,小米也领先于苹果。

贾因说,小米意识到要靠实体店夺取市场份额后,于2017年放弃了在印度实行的“纯线上销售”策略。至今,印度超50%的智能手机销售为线下销售。

去年,印度政府又推行新政策,外国零售商要想在印度开店,须将30%的制造放在印度。苹果游说印度政府,希望改变这一规定,但小米选择了遵循新规则。

经过一年多与监管机构反复交涉之后,2017年小米获得许可,在印度开设了零售店。现在,小米在印度有3,000多家Mi品牌零售店。

2019年印度政府放宽了30%开店要求,苹果于2020年在印度开设了第一家苹果专卖店。

Mi专卖店在销售手机的同时,也用于展示小米在印度销售的另一重要业务:联网设备。

贝克说:“小米的物联网生活产品实际上比预想的做得更好。”

当你走进一家Mi专卖店,你会看到电饭煲、电动平衡车、磅秤、扫地机器人,所有这些产品形成了一个围绕小米手机运行的联网智能设备生态系统。例如,Mi磅秤可接入Mi健身应用程序,可以跟踪体重指数,并提供锻炼建议。

2019年,小米的全球物联网设备营收已经达到约95亿美元,同比增长41.7%,占公司总营收的30%。在印度,小米利用智能手机作为跳板,成为智能电视和可穿戴产品的市场领先者。

野村证券(Nomura)分析师唐尼•滕说道,印度Realme和中国Oppo(均属印度五大智能手机制造商)等竞争品牌也在学小米,开始关注物联网产品,但小米有先发优势。

唐尼•滕还说:“物联网产品的生命周期远比智能手机要长,时间是最佳的屏障,可以帮助小米抵抗竞争对手,不让他们进入该市场。”但由于物联网设备的生命周期很长,小米也有压力,需要不断开发新产品。就在今年,小米在印度市场推出了新款智能手表、智能灯、智能音箱。

贾因说:“对我们而言,物联网是一个巨大的机会,我们有很多事情可以做。”

今年,小米又推出一款智能剃须刀。贾因一边用手摸着他的光头一边说,这款剃须刀还可以理发,因新冠疫情实施封锁,人们不能去理发店理发,所以这款剃须刀非常受欢迎。

尽管小米多年来一直在迎合印度消费者,但小米的中国公司身份却使其易受中印长期以来的地缘政治影响。

今年9月,印度禁用了177款中国应用程序。该国电子和信息技术部称,此举意在“确保印度网络空间的安全和主权。”

同时,代表全印度7000万商家的全印度贸易商联合会(Confederation of All India Traders)发起了一场名为“印度商品——我们的骄傲”运动,以此抵制中国产品。据当地媒体报道,该组织还列出了一份包含3000种“必须立即被印度产品取代”的中国产品名单。

贾因称,有四款小米应用程序(包括其Web浏览器和视频通话平台)在此名单中,社交媒体上的“从众心理”势必会影响小米产品的销售。

贾因是印度人,对小米的“印度名片”进行了认证,他不断告诉印度媒体:小米和其它公司一样。贾因还曾在采访中表示,小米客户“非常聪明”,应该能感觉到小米的印度精神。

在一些Mi店铺内,你会看到窗户上贴有“印度制造”标志,就是在告诉大家,小米在印度建有供应链。

对位研究公司(Counterpoint Research)分析师尼尔•沙赫认为,小米经受住了考验,仍然是印度最大的手机销售商,之所以能有此成绩,是因为在这个价格点,“没有其它手机可以替代”小米产品。

在韩国三星手机潮水般地涌向印度之前,这确实是事实,但如今形势已经发生了变化。三星手机其功能和价格都可以与小米一较高下。第一季度至第二季度,三星手机在印度的份额增长了10个百分点。

据对位研究公司统计,到了第三季度,三星已经超越小米成为印度第一,而小米在此前12个季度一直居印度第一。(Canalys和IDC等其他市场分析师表示,小米仍居领先地位。)

沙赫说:“如果印度人不抵制中国产品,如果三星未扩大其业务范围,小米可以在印度手机市场拿下30%甚至更多的份额。”

小米是否能拿下30%,具体还要看印度消费者的情绪,还有就是小米能否挡住新的挑战者。

挑战小米的不只有三星,最令人生畏的新产品可能是谷歌及其新合作伙伴Jio平台(Jio Platforms)即将推出的低价智能手机。

Jio平台是印度信实工业(Reliance Industries)的科技子公司。信实工业总部位于孟买,由印度首富穆凯什•安巴尼创立,其本土品牌也许更易于让印度消费者产生好感。(财富中文网)

本文的另一个版本刊登于《财富》杂志2020年12月/2021年1月刊,标题为《“中国苹果”在印度大行其道》

翻译:郝秀

审校:汪皓

自六年前,中国智能手机制造商小米正式进入印度市场时,就借助印度最大的宗教节日排灯节(Diwali)进行广告宣传,宣传语:“Diwali with Mi”——Mi是Xiaomi的简称。这些广告将小米与这一节日紧密结合在一起,印度人对其的期待不亚于圣诞节来临时,美国人对可口可乐北极熊广告的期待。

今年的宣传活动是将流行文化与小米的最高管理层相结合——印度首位著名的印地语说唱歌手巴巴•塞加尔,以及39岁小米全球副总裁兼印度总经理马努•库马尔•贾因一同参与制作了几段广告视频。视频里,在朗朗上口的迭句副歌“Diwali with Mi”中,两人互相调侃,谁才是更好的说唱歌手。

贾因笑着告诉《财富》杂志,这些视频“有点让人尴尬”,但它们似乎引起了印度消费者的共鸣。在系列广告视频中,最受欢迎的一段在YouTube的点击率达到了600余万次。在长达一个月的促销期间,小米卖出了900万台智能手机。

在印度,小米一个季度的手机销量一般只有1200万台,所以贾因认为,小米在排灯节(截至11月14日)的促销很成功。

这家来自北京的《财富》世界500强公司今年才刚满10岁,但其排灯节广告已经使这家公司在印度拥有了很强的影响力。小米已在印度建厂,开了几千家零售店,并努力研发印度人喜欢的手机和设备,甚至包括智能净水器。

还有像它一样成功的品牌吗?其他外国手机品牌在印度几乎已无立锥之地。

印度索波雷小米广告牌。

印度是全球增长最快的手机市场,每天有超过30万新人加入智能手机用户群,小米连续3年成为印度最畅销的手机品牌。

2020年至今,小米已经在印度销售手机2900万台,比中国还要多200万台,在印度占有四分之一的智能手机市场。

十年前小米创建时,科技媒体称它是“中国的苹果”,因为小米手机的外观时尚、价格实惠,迎合了中国不断壮大的年轻中产阶级的需求。小米趁势大肆宣传,现已上市,成为2016年全球最具价值的私人初创公司。但这惹恼了库比蒂诺的设计师们,他们嘲笑小米手机是iPhone的廉价追随者。

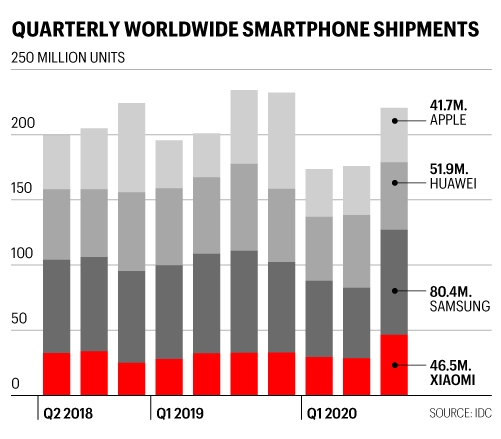

到今天,小米已然成为名副其实的手机巨头,去年营收300亿美元,市值达784亿美元。据摩根士丹利统计,小米印度营收占小米总营收的20%,小米品牌已经走出苹果阴影。2020年第三季度,小米全球手机出货量冲到第三位,首次超越苹果,排名第四。

国际数据公司(IDC)科技分析师纳夫肯达尔•辛格感叹说,小米最近在印度节节高升,但它的确遇到了很强的阻力。

今年6月,中印边境爆发冲突后,印度发起了抵制中国产品运动。这也意味着,小米在印度的发展之路可能取决于小米在印度的根基是否足以证明该品牌具有足够的印度特色。

2014年,小米带着旗舰手机Mi 3闯入印度,与其它手机相比,Mi 3拥有更快的处理器、更好的摄像头、更大的内存容量,定价却只有约200美元。

辛格说,小米手机支持4G,而三星、微软、印度品牌Micromax还停留在3G。

进入印度市场标志着小米首次在国际市场大规模扩张,它在印度次大陆推行相同的“限时特卖”策略,4年之后便成为印度第一大手机制造商。(后来,这一头衔被价格更便宜的竞争对手华为夺去。)只在网上限量销售产品,致使消费者狂热追捧,避免了生产过剩成本;不开设实体店,也就节省了管理费用。

小米与印度电商创业公司Flipkart合作,作为印度的旗舰科技巨头之一的Flipkart成为了小米手机的独家经销商。

2014年7月,第一批约1万台Mi 3智能手机只用了不到半小时就销售一空。Flipkart称,就在同一个月月末,小米Mi 3再次促销,5秒售罄;8月时第三次促销,2秒售罄。

2015年,风云突变,印度政府突然将智能手机进口关税增加一倍,达到12.5%,因为印度要推行“印度制造”战略。

当时小米的供应链几乎全部放在中国,在关税压力下,小米被迫调高印度手机售价,竞争力大幅削弱。为了寻求突破,小米与富士康于2015年首次合作,在印度设立制造基地。

印度新工厂生产的小米手机属于“印度制造”,可以避开关税。有了低价作保障,小米手机在印度的市场份额迅速攀升,2015年只有3.3%,2016年猛增到13.3%。

晨星(Morningstar)资深股票分析师丹•贝克说,小米抢在中国对手之前在国外开拓市场,他还说:“从销量看,中国市场暂时处于倒退状态,但印度仍处于增长态势,所以他们在正确的时间,瞄准了正确的市场。”

小米比苹果提前五年将供应链转移到印度,而苹果去年才开始通过富士康在印度制造iPhone。

在印度开设实体店方面,小米也领先于苹果。

贾因说,小米意识到要靠实体店夺取市场份额后,于2017年放弃了在印度实行的“纯线上销售”策略。至今,印度超50%的智能手机销售为线下销售。

去年,印度政府又推行新政策,外国零售商要想在印度开店,须将30%的制造放在印度。苹果游说印度政府,希望改变这一规定,但小米选择了遵循新规则。

经过一年多与监管机构反复交涉之后,2017年小米获得许可,在印度开设了零售店。现在,小米在印度有3,000多家Mi品牌零售店。

2019年印度政府放宽了30%开店要求,苹果于2020年在印度开设了第一家苹果专卖店。

Mi专卖店在销售手机的同时,也用于展示小米在印度销售的另一重要业务:联网设备。

贝克说:“小米的物联网生活产品实际上比预想的做得更好。”

当你走进一家Mi专卖店,你会看到电饭煲、电动平衡车、磅秤、扫地机器人,所有这些产品形成了一个围绕小米手机运行的联网智能设备生态系统。例如,Mi磅秤可接入Mi健身应用程序,可以跟踪体重指数,并提供锻炼建议。

2019年,小米的全球物联网设备营收已经达到约95亿美元,同比增长41.7%,占公司总营收的30%。在印度,小米利用智能手机作为跳板,成为智能电视和可穿戴产品的市场领先者。

野村证券(Nomura)分析师唐尼•滕说道,印度Realme和中国Oppo(均属印度五大智能手机制造商)等竞争品牌也在学小米,开始关注物联网产品,但小米有先发优势。

唐尼•滕还说:“物联网产品的生命周期远比智能手机要长,时间是最佳的屏障,可以帮助小米抵抗竞争对手,不让他们进入该市场。”但由于物联网设备的生命周期很长,小米也有压力,需要不断开发新产品。就在今年,小米在印度市场推出了新款智能手表、智能灯、智能音箱。

贾因说:“对我们而言,物联网是一个巨大的机会,我们有很多事情可以做。”

今年,小米又推出一款智能剃须刀。贾因一边用手摸着他的光头一边说,这款剃须刀还可以理发,因新冠疫情实施封锁,人们不能去理发店理发,所以这款剃须刀非常受欢迎。

尽管小米多年来一直在迎合印度消费者,但小米的中国公司身份却使其易受中印长期以来的地缘政治影响。

今年9月,印度禁用了177款中国应用程序。该国电子和信息技术部称,此举意在“确保印度网络空间的安全和主权。”

同时,代表全印度7000万商家的全印度贸易商联合会(Confederation of All India Traders)发起了一场名为“印度商品——我们的骄傲”运动,以此抵制中国产品。据当地媒体报道,该组织还列出了一份包含3000种“必须立即被印度产品取代”的中国产品名单。

贾因称,有四款小米应用程序(包括其Web浏览器和视频通话平台)在此名单中,社交媒体上的“从众心理”势必会影响小米产品的销售。

贾因是印度人,对小米的“印度名片”进行了认证,他不断告诉印度媒体:小米和其它公司一样。贾因还曾在采访中表示,小米客户“非常聪明”,应该能感觉到小米的印度精神。

在一些Mi店铺内,你会看到窗户上贴有“印度制造”标志,就是在告诉大家,小米在印度建有供应链。

全球智能手机季度季度出货量:2.5亿部。资料来源:国际数据公司(IDC)

对位研究公司(Counterpoint Research)分析师尼尔•沙赫认为,小米经受住了考验,仍然是印度最大的手机销售商,之所以能有此成绩,是因为在这个价格点,“没有其它手机可以替代”小米产品。

在韩国三星手机潮水般地涌向印度之前,这确实是事实,但如今形势已经发生了变化。三星手机其功能和价格都可以与小米一较高下。第一季度至第二季度,三星手机在印度的份额增长了10个百分点。

据对位研究公司统计,到了第三季度,三星已经超越小米成为印度第一,而小米在此前12个季度一直居印度第一。(Canalys和IDC等其他市场分析师表示,小米仍居领先地位。)

沙赫说:“如果印度人不抵制中国产品,如果三星未扩大其业务范围,小米可以在印度手机市场拿下30%甚至更多的份额。”

小米是否能拿下30%,具体还要看印度消费者的情绪,还有就是小米能否挡住新的挑战者。

挑战小米的不只有三星,最令人生畏的新产品可能是谷歌及其新合作伙伴Jio平台(Jio Platforms)即将推出的低价智能手机。

Jio平台是印度信实工业(Reliance Industries)的科技子公司。信实工业总部位于孟买,由印度首富穆凯什•安巴尼创立,其本土品牌也许更易于让印度消费者产生好感。(财富中文网)

本文的另一个版本刊登于《财富》杂志2020年12月/2021年1月刊,标题为《“中国苹果”在印度大行其道》

翻译:郝秀

审校:汪皓

Ever since Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi entered the Indian market six years ago, it has run an ad campaign targeting India’s biggest religious festival, Diwali, that features a clever tagline: “Diwali with Mi”—Mi being shorthand for Xiaomi. The ads are so closely associated with the holiday that Indians look forward to them the way Americans anticipate Coca-Cola’s polar bear ads at Christmas.

This year’s campaign was a mashup of pop culture and the C-suite, featuring Baba Sehgal, India’s first breakout Hindi rapper, and Xiaomi’s 39-year-old global vice president and managing director of India, Manu Kumar Jain—or Manu-J, for the purposes of the videos. In between a catchy refrain of “Diwali with Mi,” the two trade zingers about who’s the better rapper.

Jain tells Fortune, with a laugh, that the videos were “embarrassing,” but they seemed to strike a chord with Indian consumers. The most popular video in the series was viewed on YouTube more than 6 million times, and Xiaomi sold 9 million smartphones during the monthlong sales period. The brand usually sells 12 million phones in a single quarter in India, so Jain deemed this Diwali, which ended Nov. 14, Xiaomi’s best yet.

The Diwali ads are one way the 10-year-old Beijing-based technology company has embedded itself in India. It has also moved manufacturing to the subcontinent, earned the right to open thousands of retail stores, and developed phones and other gadgets with the Indian consumer in mind—smart water purifier, anyone? It’s gone all in where other foreign phone brands have danced around the edges.

The investment in the world’s fastest-growing mobile market, where over 300,000 people power up their first smartphone every day, has made Xiaomi India’s bestselling smartphone brand for three years running. In 2020 so far, it has sold 29 million phones, 2 million more than in China, to control a full quarter of India’s smartphone market.

After it launched a decade ago, tech journalists called Xiaomi the “Apple of China,” because of its sleek, affordable phones that catered to China’s young, growing middle class. The association fueled Xiaomi hype—the now public company was the world’s most valuable private startup in 2016—but it annoyed designers in Cupertino who derided Xiaomi’s handsets as cheap iPhone wannabes. Xiaomi is now a bona fide phone giant, with $30 billion in revenue last year and a market capitalization of $78.4 billion. And Xiaomi’s India sales—responsible for 20% of all revenue, according to Morgan Stanley—have helped pull the brand fully out of Apple’s shadow, at least by one measure: In the third quarter of 2020, Xiaomi’s worldwide phone shipments landed it in third place, ahead of Apple (No. 4) for the first time.

Navkendar Singh, a tech analyst at consultancy International Data Corporation (IDC), describes Xiaomi’s recent track record in India as “growing, growing, growing,” but it does face one strong headwind: Indian consumers’ anti-China sentiment. A border skirmish between Indian and Chinese military forces in June ignited boycotts of Chinese goods. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s nationalist government keeps stoking the backlash, which means Xiaomi’s trajectory on the subcontinent may depend on whether the roots it planted in India qualify the brand as Indian enough.

Xiaomi landed in India in 2014 with its flagship Mi 3 phone, which featured a faster processor, better camera, and more memory than other phones at its price point of roughly $200. What’s more, Singh says, Xiaomi offered 4G services, while competitors like Samsung, Microsoft, and Indian brand Micromax were stuck on 3G.

India represented Xiaomi’s first major international expansion, and it brought to the subcontinent the same “flash sale” strategy that had catapulted it briefly to No. 1 in its home market just four years after its launch. (It later lost that title to cheaper rivals as well as Beijing’s champion telecom brand, Huawei.) Selling products only online, in limited batches, created a frenzy among buyers and avoided overproduction costs; eschewing physical stores meant saving on overhead.

Xiaomi partnered with Flipkart, an Indian e-commerce startup that is now one of the nation’s flagship tech giants, as the sole distributor of its phones. The first batch of roughly 10,000 Mi 3 smartphones sold out within half an hour of launch in July 2014. A second flash sale later that same month sold out in five seconds, and a third round in August sold out in two ticks, Flipkart said.

The mania could have come to a sudden stop in 2015, when Modi’s administration doubled tariffs on smartphone imports to 12.5% as part of its “Make in India” initiative to onshore manufacturing. Had Xiaomi kept its supply chain in place—it was almost entirely based in China at the time—the tariffs would have forced it to raise prices, forfeiting a big competitive edge. Instead, it partnered with phone assembler Foxconn to set up a manufacturing site in India in 2015, a first for both companies.

The new Indian factory earned Xiaomi the all-important Made in India label and shielded it from Modi’s tariffs. With its low price point secured, Xiaomi India’s market share leaped from 3.3% in 2015 to 13.3% the next year.

Xiaomi shifted its focus beyond the mainland before many of its Chinese rivals, says Dan Baker, a senior equity analyst at Morningstar. “The Chinese market’s gone backward for a while, in terms of volumes, but India’s still been growing, so they focused on the right market at the right time.”

In moving its supply chain to India, Xiaomi was a half-decade ahead of Apple, which only started manufacturing iPhones in India—also through Foxconn—last year.

Xiaomi also beat Apple to opening up physical stores on the subcontinent. Jain says Xiaomi abandoned its online-only sales strategy in India in 2017 after realizing that stealing market share demanded a physical presence. Even now, over 50% of all smartphone sales in India are made offline.

Until last year, the Modi government kept foreign retailers from setting up their own stores, unless they sourced 30% of their manufacturing from India. Unlike Apple, which lobbied Modi’s government to change the rule, Xiaomi opted to meet it. After a year of back and forth with regulators, Xiaomi in 2017 got the green light to open its own retail outlets. Xiaomi now has more than 3,000 Mi-branded stores across India. In 2019, Modi’s government relaxed the 30% rule, and Apple is due to open its first Apple Store in India next year.

The Mi stores sell phones, yes, but they also serve as showrooms for another bright spot in Xiaomi’s India business: Internet-connected gadgets. “Probably the part of Xiaomi’s business that has done better than expected … is the Internet of Things (IoT) lifestyle products,” says Baker.

Walk into a Mi store and you’ll encounter rice cookers, electric scooters, weighing scales, and robot vacuums—an entire ecosystem of interconnected smart devices that orbit the Xiaomi mobile phone. The Mi scale, for example, connects to a Mi fitness app that can track body mass index and suggests relevant exercise regimes.

In 2019, Xiaomi’s IoT device sales globally generated roughly $9.5 billion for the company, an increase of 41.7% from the year before and about 30% of the company’s total revenue. In India, Xiaomi has parlayed its pole position in smartphones to be the market leader in smart TVs and wearable tech.

Rival brands like Indian firm Realme and China’s Oppo—both top-five smartphone makers in India—are starting to target the same IoT segments, says Nomura analyst Donnie Teng, but Xiaomi has a first-mover advantage. “The life cycle for IoT products is much longer than the one for smartphones, so time is the best barrier Xiaomi can deploy to prevent competitors from entering the market,” Teng says. But since IoT devices last for so long, Xiaomi is under pressure to keep developing new products. Just this year, Xiaomi has launched new smartwatches, smart lights, and smart speakers in the Indian market.

“We believe the Internet of Things can be a big opportunity for us because there’s so much more we can do,” Jain says. Xiaomi also launched a smart beard trimmer this year. It doubles as a hair trimmer, Jain says, running a hand over his shaved head, and it’s seen “off the chart” demand, thanks to pandemic lockdowns keeping everyone away from barbershops.

Despite years of ingratiating its brand with Indian consumers, Xiaomi’s identity as a Chinese company has left it susceptible to the whims of India and China’s long-standing geopolitical rivalry.

Modi’s government retaliated by banning 177 Chinese apps, a move the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology said was “to ensure safety, security, and sovereignty of Indian cyberspace.” Meanwhile, the Confederation of All India Traders—a union that says it represents 70 million merchants across India—called for a boycott of Chinese goods with a campaign dubbed “Indian Goods—Our Pride.” According to local media, the group identified 3,000 categories of goods that “must immediately be replaced by Indian products.”

Four Xiaomi apps, including its web browser and video-calling platform, were caught in the purge and, according to Jain, a “mob mentality” on social media threatened its sales.

Jain, himself an Indian national, responded by touting Xiaomi’s adopted Indian identity, telling local media that Xiaomi was “as Indian as any other company here.” In other interviews, he said Xiaomi customers are “very intelligent” and would be able to identify the company’s Indian “spirit.” Lest they forget, a few Mi stores plastered “Made in India” signs in their windows that pointed to Xiaomi’s local supply chain.

Initially, Xiaomi weathered the anti-China movement and remained India’s top smartphone seller because in India “there [were] no real alternatives” to Chinese phones that are still in Xiaomi’s price territory, says Neil Shah, an analyst at Counterpoint Research. (Apple, a U.S. brand, is considered higher-end; the cheapest iPhone on the Apple Store in India is $526.)

That was true, at least, until South Korea’s Samsung began flooding India with phones that could compete with Xiaomi’s features and affordability. Samsung’s phones hit the market just as anti-China attitudes were ramping up. Between the first and second quarters, Samsung’s smartphone market share in India grew 10 percentage points. By the third quarter, it had overtaken Xiaomi as No. 1, according to data from Counterpoint Research, ending Xiaomi’s streak of 12 consecutive quarters on top. (Other market analysts like Canalys and IDC show Xiaomi retaining its lead.)

“If there were no anti-China sentiments in India, and Samsung didn’t expand its portfolio, Xiaomi would have gone to 30% or more of India’s smartphone market,” says Shah.

Whether Xiaomi ever reaches that threshold will depend on it shaking the anti-China stigma for good and fending off new challengers. It’s not just Samsung; the most formidable newcomer could be the low-price smartphone that’s forthcoming from Google and its new partner, Jio Platforms.

Jio is the digital arm of Reliance Industries, a conglomerate based in Mumbai and founded by Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man, and its homegrown credentials may foster more goodwill among Indian consumers than any amount of battle rap can muster.

A version of this article appears in the December 2020/January 2021 issue of Fortune with the headline, "The 'Apple of China' goes big in India."