两位传奇投资人警告:股市飓风将至

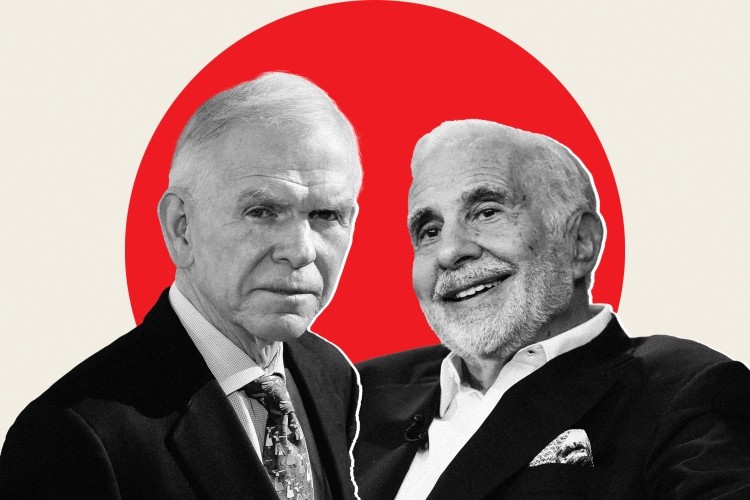

上周,史上最具洞察力的两位股市智者、从事投机热潮预测数十载的卡尔•伊坎和杰里米•格兰瑟姆公开指出,牛市已经失序,股票价格被严重高估,预计出现大幅抛售。同一周,从盲目乐观的华尔街基金经理到痴迷于当日交易的X世代投资者却无视警告,掀起了又一轮购买狂潮。1月7日,也就是上周四,标准普尔500指数、道琼斯指数和纳斯达克指数均被推至新高。

下月将满85岁高龄的伊坎和现年82岁的格兰瑟姆在市场预测和风险规避方面的经验加起来约有120年。伊坎拥有工业和投资集团公司Icahn Enterprises(市值118亿美元)90%以上的股份,还持有Cheniere Energy、Newell Brands、施乐控股(Xerox Holdings)等公司数十亿美元的股份。尽管他于2019年底将业务从曼哈顿迁到了迈阿密,但依旧和以前一样忙碌。英国人格兰瑟姆则是Grantham、Mayo、Van Otterloo、GMO的联合创始人和长期投资策略师,管理着650亿美元的资产。

如今,格兰瑟姆的兴趣主要在他的基金支持的环保事业上,并为此投入了92%的财富。虽然他已经不再遴选个别股票,但仍然密切关注市场的总体走向,乐于对各类资产的今昔状况进行对比分析,对过高或过低的资产给出预警。格兰瑟姆和伊坎的预测角度不同。本文作者曾经多次采访伊坎,但从未听到这位传奇投资者谈论市盈率、贴现率、风险溢价或其他专家在评估市场状况时常用的指标。毫无疑问,伊坎对所有数字了如指掌,但他似乎更相信直觉,直觉告诉他:我以前见过这种情况,它总是意味着麻烦。

相比之下,格兰瑟姆习惯用各种指标和数据支撑自己的观点。但此次让他和伊坎警觉的,与其说是数字,不如说是气氛。世界疯了,到处是疯狂的猜测,到处是狂热者,这些人控制了市场,任何有关股市会下跌的暗示都令他们愤怒。为何伊坎和格兰瑟姆会同时发出警告?因为在这两位久经沙场的智者看来,眼下,尤其是过去几周,股市上演的一幕堪称“疯子接管了疯人院”,而这正预示着大崩盘。

我曾经在2000年用疯狂来形容纳斯达克指数,并在2004年出现大规模房产抛售前警告房价已经过热,这证明疯狂可以持续相当长时间。在纳斯达克的例子中,很显然,多头违背现实,过度夸大了未来利润大幅增长的预期。在房地产热潮中,房价则偏离了作为定价基础的房屋和公寓租金水平,完全失控。两个案例里的买家都相信,估值已经永久性地达到了一个比过去高得多的新平台。结果,现实袭来,纳斯达克指数下跌82%,房价下跌超过50%,二者均远低于上涨前的水平。

1月4日,伊坎在与美国消费者新闻与商业频道(CNBC)的主播斯科特•瓦普纳的非直播交流中表达了自己的看法。伊坎在2020年4月25日就曾经对股价过高发出警告,当时的标普指数比现在低25%,但他显然认为,从那以后,股市已经从泡沫走向疯狂。此次,他暗示瓦普纳,市场将出现大规模抛售。“我这辈子见过很多疯狂反弹,其中不乏大量错价股票,但它们都有一个共同点,就是最终都碰了壁,陷入痛苦的大调整。没有人能够预测这种情况什么时候会发生,但当它到来时,一定要小心。”

伊坎没有具体说明他在防范可能发生的灾难方面采取了什么措施,但他提到,他已经关注一段时间了,而且“做了相当不错的防范”。伊坎最后警告说,“[过去的疯狂反弹]还有一个共同点:人们总是说‘这次不一样’,但从来没有什么不一样。”

格兰瑟姆在GMO的网站上发表了一篇题为《等待最后一支舞:在泡沫后期进行资产配置的危险》的长文,表达了自己的看法。与伊坎的笼统警告不同,格兰瑟姆的分析详细而具体,也更显紧迫,他甚至大胆预测:飓风将至。格兰瑟姆说道:“自2009年以来的长期牛市终于变成了一个成熟饱满、宏大壮观的泡泡。股市被极度高估,股价暴涨,发行疯狂,投资者的行为变得歇斯底里。我认为这一事件将成为金融史上最大的泡沫,堪比南海泡沫、1929大萧条和2000年大崩盘。”他承认,逆流而动需要勇气。“每一次心理误判,都会让投资者受到诱惑。”

格兰瑟姆列举了自己四次正确预见到危机将至并抛售股票的经历。2008年,他几近准确地预测到市场高点,并“抓住”2009年初的低点重新进入。1987年,日本股市的市盈率由25倍涨至40倍,他意识到泡沫正在生成,卖掉了所有头寸。随后三年,股价一度飙升,1990年崩盘前的市盈率甚至达到65倍。尽管如此,格兰瑟姆说自己做了正确的决定:以远低于三年前抛出时的价格抄底。1997年,他在标普指数超过1929年峰值时减持了一半美股,此后美股一路高涨直至2000年6月。但GMO在2002年末股价下跌40%时大笔买入,此举在随后几年带来的回报远胜过抱定原本的投资组合大起大落。

格兰瑟姆指出,股市陷入疯狂有两点共性。第一是股价在后期加速上涨,这预示着离崩盘越来越近。眼下的情况正是如此:标普指数继2020年8月中旬回升到2月创下的历史高点以来又涨了12.4%,纳斯达克自2020年10月底以来已经上涨20%。第二,“回顾历史,大泡沫后期总是伴随着投资者的疯狂行为,尤其是个人投资者。”他补充说,在始于2009年的这轮牛市的头10年里,股价逐步上涨,但基本没有出现过度疯狂的现象。然而现在,“价格越高就涨得越高”的说法成了新常态。格兰瑟姆以柯达(Kodak)、赫兹(Hertz)、Nikola的短暂辉煌,以及投资者对特斯拉的持久痴迷为例,认为这些都是市场陷入疯狂的标志。这位热心的环保主义者强调,尽管他很自豪地开着Model 3,但他“最津津乐道的关于特斯拉的趣闻”是,他们每卖出一辆车,市值就被推高125万美元,相比于通用汽车(GM)的9000美元高出近140倍。

投资者对IPO公司的渴望是另一个不祥的信号。格兰瑟姆指出,去年共有480家公司公开上市,其中包括248家特殊目的收购公司,大大超过2000年408家的纪录。他认为关键问题在于,此轮超级牛市与以往有很大不同。以前的牛市均具有两大特点:一是美联储(Federal Reserve)为市场提供了宽松的信贷,且保持低利率;另一个,他称为“近乎完美的经济”,即能在相当长一段时间内保持强劲、稳定的势头。“如今经济受到重创,情况完全不同。”他说。随着新冠疫情肆虐,美国经济正在面临二度探底的危险,即便危机过去,失业率也可能居高不下。令格兰瑟姆惊讶的是,与失业率处于历史低点,销售额、利润和收入激增时相比,现在的市盈率却高得多。“眼下的市盈率处于历史高峰,而经济处于最低谷。”在格兰瑟姆看来,这种悬殊绝非特殊目的收购公司的涌现可以解释,而是体现了市场的狂热。

根据过往的经验,格兰瑟姆认为这是暴风雨前的艳阳。对于看涨者的主要观点,即目前的极低利率以及美联储对未来几年保持低利率的承诺能够保证股价长期高企,他表示怀疑。“2020年时人们都认为精心设计的低利率始终可以防止资产价格下跌”,但低利率和超宽松货币政策并未在2000年阻止股市崩盘。

我同意格兰瑟姆的观点,低利率并不能够保证高估值。考虑了通胀的“实际”利率反映出对资本的需求,且往往与经济增长挂钩。经济增速越快,新投资的利润就越高,争夺投资资金的公司也越多。竞争拉高了利率。如果利率可以长时间保持在低位,可能意味着对资本的需求较弱,因为企业是在原地踏步,而不是迅速扩张,整体经济亦是如此。所以低利率通常意味着低增长和低利润。看涨者用年复一年快速增长的收益为眼下这些超级昂贵的短跑健儿堆出了庞大的市值。他们以为未来利率将处于超低水平,利润增长则将达到前所未有的超高水平。

然而历史经验并不支持“低利率可以作为助推剂”的看法。监管着1450亿美元ETFs和共同基金投资策略的Research Affiliates的董事长罗布•阿诺特指出,20世纪50年代,十年期美国国债的收益率为1.0%至1.5%,但市盈倍数还不到目前的三分之一。格兰瑟姆还提到,曾经预报了2009年房价崩盘和2000年科技泡沫的耶鲁大学经济学家罗伯特•希勒说,按照10年平均收益计算,尽管现在的市盈倍数比1929年和2007年的高,但目前的高价位在某种程度上可能是合理的。理由是:眼下股票的可能回报和债券的可能收益之间的差距较之于那两个时期要大。格兰瑟姆和阿诺特都不认同“股票比债券好得多,因此仍然不错”的解读。阿诺特认为,“希勒真正的意思是,债券太糟了,相比较而言,股票还没有那么糟。”对此,格兰瑟姆赞同道:“从历史角度来看,债券甚至比股票还贵。天啊!”

格兰瑟姆承认,准确预测峰值是不可能的。事实上,他常常在触顶前就撤出价格过高的市场。但他强烈暗示,音乐将停,舞蹈将止,一切很快就会结束。他给出了两个理由:多头的热情日益高涨,标志着狂热的临终剧痛的股价加速攀升。格兰瑟姆说,自2020年夏天以来一直在观望、错过了股市大幅上涨的投资者做出了正确的决定,这意味着他们能够在即将到来的灾难之后以更低的价格大量买入。这些话,多头一定不爱听。但事实证明,格兰瑟姆和伊坎数十载的成功策略就是在事态疯狂时果断退出,然后在投资者纷纷恐慌之际,趁着股价跳水的低点大笔买入。这才是这些传奇人物渴望的疯狂。(财富中文网)

译者:胡萌琦

上周,史上最具洞察力的两位股市智者、从事投机热潮预测数十载的卡尔•伊坎和杰里米•格兰瑟姆公开指出,牛市已经失序,股票价格被严重高估,预计出现大幅抛售。同一周,从盲目乐观的华尔街基金经理到痴迷于当日交易的X世代投资者却无视警告,掀起了又一轮购买狂潮。1月7日,也就是上周四,标准普尔500指数、道琼斯指数和纳斯达克指数均被推至新高。

下月将满85岁高龄的伊坎和现年82岁的格兰瑟姆在市场预测和风险规避方面的经验加起来约有120年。伊坎拥有工业和投资集团公司Icahn Enterprises(市值118亿美元)90%以上的股份,还持有Cheniere Energy、Newell Brands、施乐控股(Xerox Holdings)等公司数十亿美元的股份。尽管他于2019年底将业务从曼哈顿迁到了迈阿密,但依旧和以前一样忙碌。英国人格兰瑟姆则是Grantham、Mayo、Van Otterloo、GMO的联合创始人和长期投资策略师,管理着650亿美元的资产。

如今,格兰瑟姆的兴趣主要在他的基金支持的环保事业上,并为此投入了92%的财富。虽然他已经不再遴选个别股票,但仍然密切关注市场的总体走向,乐于对各类资产的今昔状况进行对比分析,对过高或过低的资产给出预警。格兰瑟姆和伊坎的预测角度不同。本文作者曾经多次采访伊坎,但从未听到这位传奇投资者谈论市盈率、贴现率、风险溢价或其他专家在评估市场状况时常用的指标。毫无疑问,伊坎对所有数字了如指掌,但他似乎更相信直觉,直觉告诉他:我以前见过这种情况,它总是意味着麻烦。

相比之下,格兰瑟姆习惯用各种指标和数据支撑自己的观点。但此次让他和伊坎警觉的,与其说是数字,不如说是气氛。世界疯了,到处是疯狂的猜测,到处是狂热者,这些人控制了市场,任何有关股市会下跌的暗示都令他们愤怒。为何伊坎和格兰瑟姆会同时发出警告?因为在这两位久经沙场的智者看来,眼下,尤其是过去几周,股市上演的一幕堪称“疯子接管了疯人院”,而这正预示着大崩盘。

我曾经在2000年用疯狂来形容纳斯达克指数,并在2004年出现大规模房产抛售前警告房价已经过热,这证明疯狂可以持续相当长时间。在纳斯达克的例子中,很显然,多头违背现实,过度夸大了未来利润大幅增长的预期。在房地产热潮中,房价则偏离了作为定价基础的房屋和公寓租金水平,完全失控。两个案例里的买家都相信,估值已经永久性地达到了一个比过去高得多的新平台。结果,现实袭来,纳斯达克指数下跌82%,房价下跌超过50%,二者均远低于上涨前的水平。

1月4日,伊坎在与美国消费者新闻与商业频道(CNBC)的主播斯科特•瓦普纳的非直播交流中表达了自己的看法。伊坎在2020年4月25日就曾经对股价过高发出警告,当时的标普指数比现在低25%,但他显然认为,从那以后,股市已经从泡沫走向疯狂。此次,他暗示瓦普纳,市场将出现大规模抛售。“我这辈子见过很多疯狂反弹,其中不乏大量错价股票,但它们都有一个共同点,就是最终都碰了壁,陷入痛苦的大调整。没有人能够预测这种情况什么时候会发生,但当它到来时,一定要小心。”

伊坎没有具体说明他在防范可能发生的灾难方面采取了什么措施,但他提到,他已经关注一段时间了,而且“做了相当不错的防范”。伊坎最后警告说,“[过去的疯狂反弹]还有一个共同点:人们总是说‘这次不一样’,但从来没有什么不一样。”

格兰瑟姆在GMO的网站上发表了一篇题为《等待最后一支舞:在泡沫后期进行资产配置的危险》的长文,表达了自己的看法。与伊坎的笼统警告不同,格兰瑟姆的分析详细而具体,也更显紧迫,他甚至大胆预测:飓风将至。格兰瑟姆说道:“自2009年以来的长期牛市终于变成了一个成熟饱满、宏大壮观的泡泡。股市被极度高估,股价暴涨,发行疯狂,投资者的行为变得歇斯底里。我认为这一事件将成为金融史上最大的泡沫,堪比南海泡沫、1929大萧条和2000年大崩盘。”他承认,逆流而动需要勇气。“每一次心理误判,都会让投资者受到诱惑。”

格兰瑟姆列举了自己四次正确预见到危机将至并抛售股票的经历。2008年,他几近准确地预测到市场高点,并“抓住”2009年初的低点重新进入。1987年,日本股市的市盈率由25倍涨至40倍,他意识到泡沫正在生成,卖掉了所有头寸。随后三年,股价一度飙升,1990年崩盘前的市盈率甚至达到65倍。尽管如此,格兰瑟姆说自己做了正确的决定:以远低于三年前抛出时的价格抄底。1997年,他在标普指数超过1929年峰值时减持了一半美股,此后美股一路高涨直至2000年6月。但GMO在2002年末股价下跌40%时大笔买入,此举在随后几年带来的回报远胜过抱定原本的投资组合大起大落。

格兰瑟姆指出,股市陷入疯狂有两点共性。第一是股价在后期加速上涨,这预示着离崩盘越来越近。眼下的情况正是如此:标普指数继2020年8月中旬回升到2月创下的历史高点以来又涨了12.4%,纳斯达克自2020年10月底以来已经上涨20%。第二,“回顾历史,大泡沫后期总是伴随着投资者的疯狂行为,尤其是个人投资者。”他补充说,在始于2009年的这轮牛市的头10年里,股价逐步上涨,但基本没有出现过度疯狂的现象。然而现在,“价格越高就涨得越高”的说法成了新常态。格兰瑟姆以柯达(Kodak)、赫兹(Hertz)、Nikola的短暂辉煌,以及投资者对特斯拉的持久痴迷为例,认为这些都是市场陷入疯狂的标志。这位热心的环保主义者强调,尽管他很自豪地开着Model 3,但他“最津津乐道的关于特斯拉的趣闻”是,他们每卖出一辆车,市值就被推高125万美元,相比于通用汽车(GM)的9000美元高出近140倍。

投资者对IPO公司的渴望是另一个不祥的信号。格兰瑟姆指出,去年共有480家公司公开上市,其中包括248家特殊目的收购公司,大大超过2000年408家的纪录。他认为关键问题在于,此轮超级牛市与以往有很大不同。以前的牛市均具有两大特点:一是美联储(Federal Reserve)为市场提供了宽松的信贷,且保持低利率;另一个,他称为“近乎完美的经济”,即能在相当长一段时间内保持强劲、稳定的势头。“如今经济受到重创,情况完全不同。”他说。随着新冠疫情肆虐,美国经济正在面临二度探底的危险,即便危机过去,失业率也可能居高不下。令格兰瑟姆惊讶的是,与失业率处于历史低点,销售额、利润和收入激增时相比,现在的市盈率却高得多。“眼下的市盈率处于历史高峰,而经济处于最低谷。”在格兰瑟姆看来,这种悬殊绝非特殊目的收购公司的涌现可以解释,而是体现了市场的狂热。

根据过往的经验,格兰瑟姆认为这是暴风雨前的艳阳。对于看涨者的主要观点,即目前的极低利率以及美联储对未来几年保持低利率的承诺能够保证股价长期高企,他表示怀疑。“2020年时人们都认为精心设计的低利率始终可以防止资产价格下跌”,但低利率和超宽松货币政策并未在2000年阻止股市崩盘。

我同意格兰瑟姆的观点,低利率并不能够保证高估值。考虑了通胀的“实际”利率反映出对资本的需求,且往往与经济增长挂钩。经济增速越快,新投资的利润就越高,争夺投资资金的公司也越多。竞争拉高了利率。如果利率可以长时间保持在低位,可能意味着对资本的需求较弱,因为企业是在原地踏步,而不是迅速扩张,整体经济亦是如此。所以低利率通常意味着低增长和低利润。看涨者用年复一年快速增长的收益为眼下这些超级昂贵的短跑健儿堆出了庞大的市值。他们以为未来利率将处于超低水平,利润增长则将达到前所未有的超高水平。

然而历史经验并不支持“低利率可以作为助推剂”的看法。监管着1450亿美元ETFs和共同基金投资策略的Research Affiliates的董事长罗布•阿诺特指出,20世纪50年代,十年期美国国债的收益率为1.0%至1.5%,但市盈倍数还不到目前的三分之一。格兰瑟姆还提到,曾经预报了2009年房价崩盘和2000年科技泡沫的耶鲁大学经济学家罗伯特•希勒说,按照10年平均收益计算,尽管现在的市盈倍数比1929年和2007年的高,但目前的高价位在某种程度上可能是合理的。理由是:眼下股票的可能回报和债券的可能收益之间的差距较之于那两个时期要大。格兰瑟姆和阿诺特都不认同“股票比债券好得多,因此仍然不错”的解读。阿诺特认为,“希勒真正的意思是,债券太糟了,相比较而言,股票还没有那么糟。”对此,格兰瑟姆赞同道:“从历史角度来看,债券甚至比股票还贵。天啊!”

格兰瑟姆承认,准确预测峰值是不可能的。事实上,他常常在触顶前就撤出价格过高的市场。但他强烈暗示,音乐将停,舞蹈将止,一切很快就会结束。他给出了两个理由:多头的热情日益高涨,标志着狂热的临终剧痛的股价加速攀升。格兰瑟姆说,自2020年夏天以来一直在观望、错过了股市大幅上涨的投资者做出了正确的决定,这意味着他们能够在即将到来的灾难之后以更低的价格大量买入。这些话,多头一定不爱听。但事实证明,格兰瑟姆和伊坎数十载的成功策略就是在事态疯狂时果断退出,然后在投资者纷纷恐慌之际,趁着股价跳水的低点大笔买入。这才是这些传奇人物渴望的疯狂。(财富中文网)

译者:胡萌琦

During the week of Jan. 4, two of the all-time great stock market sages—who've been expert at calling speculative crazes for decades—charged that the bulls had lost their marbles. Carl Icahn and Jeremy Grantham went public claiming that equities are vastly overpriced and due for a steep selloff. The same week, the cockeyed optimists from Wall Street money managers to Gen Xers hooked on day trading ignored their warning, staging still another buying frenzy that on last Thursday, Jan. 7, pushed the S&P 500, Dow, and Nasdaq to fresh records.

Between them, Icahn, who'll turn 85 next month, and Grantham, at 82, have a total of around 120 years of experience navigating the markets and skirting just the kinds of disasters they see coming. Icahn owns over 90% of industrial conglomerate and investment vehicle Icahn Enterprises (market cap: $11.8 billion), and holds billions more in shares of companies as diverse as Cheniere Energy, Newell Brands, and Xerox Holdings. Though Icahn moved his operations from Manhattan to Miami in late 2019, he remains as busy an activist as ever. Grantham, a native of Britain, is cofounder and long-term investment strategist at Grantham, Mayo, Van Otterloo, or GMO, the $65 billion asset management stalwart.

Today, Grantham’s interests center on his foundation supporting environmental causes, the institution he's backed with 92% of his wealth. But though he's no longer picking individual stocks, Grantham follows the market's overall trajectory closely, and he prides himself on calling when types of assets are excessively cheap or pricey compared with past periods. Grantham and Icahn come at their forecasts from different angles. This writer has interviewed Icahn many times, and he's never heard the storied investor talk about price-to-earnings multiples, discount rates, risk premiums, or any of the other metrics the experts typically cite in assessing where the market stands. I have no doubt Icahn knows all the numbers, but he appears to rely on instincts that tell him, I've seen this scenario before, and it always spells trouble.

By contrast, Grantham summons sundry metrics and data to support his case. But what sounds the alarm for Grantham, as for Icahn, isn't so much the numbers as the atmospherics, the sense of a world gone mad, of wild speculation, of zealots—outraged at any suggestion stocks will drop—taking charge. What prompted Icahn and Grantham to issue their warnings at the same time? The veterans both see the same "lunatics are taking over the asylum" script taking hold, especially in the last few weeks, that presaged past meltdowns.

This reporter called the Nasdaq frenzy in 2000 and warned that housing prices had gone nuts in 2004, two years before the giant selloff: proof the craziness can last a long time. In the case of the Nasdaq, it was clear that bulls had wildly overblown expectations for huge future growth in profits that couldn't happen. In the housing craze, prices had become totally detached from the force that governs them, the level of rents on homes and apartments. In both cases, the bulls bought the notion that valuations had permanently reached a new, much higher plateau than in the past. When reality struck, the Nasdaq dropped 82%, and housing prices retreated over 50%. The falls took prices well below their levels when the run-ups began.

Icahn made his comments on Jan. 4 in an off-air conversation with CNBC anchor Scott Wapner. Icahn had warned that equities were overvalued on April 25, 2020, when the S&P was 25% cheaper than today, but he clearly believed things had tilted from frothy to crazy since. This time, he suggested to Wapner that a major selloff is looming. "In my day, I've seen a lot of wild rallies with a lot of mis-priced stocks, but there's always one thing they all have in common," declared Icahn. “Eventually they hit a wall and go into a major painful correction, and nobody can predict when it will happen. But when it does, look out below."

Icahn didn't specify any bets he's making to guard against a possible cataclysm, but he did note that he's been concerned for some time and is "pretty well-hedged." In conclusion, Icahn cautioned, "Another thing [these wild rallies] have in common: It's always said ‘It's different this time,’ but it never turns out to be the truth."

Grantham delivered his salvo in a long essay on GMO's website titled "Waiting for the Last Dance: The Hazards of Asset Allocation in the Late Stages of a Bubble." While Icahn's warning is general, Grantham is extremely specific, detailed, and even more dire—he even dares predicting that the hurricane could strike soon. "The long, long bull market since 2009 has finally matured into a full-fledged, epic bubble," writes Grantham. "Featuring extreme overvaluation, explosive price increases, frenzied issuance, and hysterically speculative investor behavior. I believe this event will be recorded as one of the great bubbles in financial history, right along with the South Sea bubble, 1929, and 2000." He acknowledges that going against the crowd will take courage. "Every fault of human psychology will be pulling investors in," he cautions.

Grantham cites four occasions when he correctly saw trouble brewing and dumped stocks. In 2008, he came close to calling the market top, and also "nailed" the lows of early 2009, when he jumped back in. In 1987, he saw a bubble building in Japan when its market P/E hit 40, dwarfing the previous high of 25. Grantham sold all of his positions but was three years early. Shares soared for a while, driving multiples to 65 before the market collapsed in 1990. Still, Grantham says he made the right call: He scooped up bargains at prices far below where he had bailed out three years before. He also lowered his U.S. holdings by half in 1997 when the S&P multiple surpassed its 1929 peak, only to soar until June 2000. But GMO grabbed shares during the 40% drop through late 2002, a coup that produced much better returns in future years than holding the same portfolio through the roller-coaster ride.

Grantham notes two factors that are common to these crazes. The first is that prices spike at an accelerating pace in the late stages, signaling that we're getting closer and closer to a crash. That's precisely what's happening now: Since regaining its all-time high set in February by mid-August, the S&P has vaulted another 12.4%, and since late October, the Nasdaq has jumped 20%. Second, as Grantham writes, "The single most dependable feature of the late stages of the great bubbles of history has been really crazy investor behavior, especially on the part of individuals." He adds that for the first 10 years of this bull market, which began in 2009, stocks gradually ground higher, and were getting more and more expensive, but wild excesses were mainly absent. Now the mantra that “the higher prices go, the higher they'll go from there” is the new normal. Grantham cites the fleeting embrace of Kodak, Hertz, and Nikola, and especially enduring infatuation with Tesla, as hallmarks of a market gone loco. The ardent environmentalist stresses that though he proudly drives the Model 3, his "favorite Tesla tidbit" is that it boasts a market cap of $1.25 million for every car it sells, 140 times the GM figure of $9,000.

Investors' craving for IPOs is another bad sign. Grantham notes that last year saw 480 public offerings, including 248 SPACs (special purpose acquisition companies), easily eclipsing the record 408 IPOs in 2000. In one key respect, he says, this over-the-top bull market is vastly different from the others. Its predecessors shared two main features: a lenient Federal Reserve that flooded markets with easy credit and held interest rates low, and what he calls a "near-perfect economy" boasting strong, steady growth that looked like it would last a long time. "Today's wounded economy is totally different," he says. America's facing the danger of a double dip as the COVID-19 pandemic rages on, and unemployment is likely to remain stubbornly high even when the crisis ends. Grantham marvels that prices relative to earnings are now much higher than when the jobless rate was at historic lows and sales, profits, and incomes were surging. "Today's P/E ratio is in the top few percent of the historical range, and the economy is in the worst few percent," he says. For Grantham, that divergence tells us more about the raging market fever than the rash of new SPACs.

Based on what he's seen in the sunny preludes to past storms, Grantham doesn't buy the bulls' main argument: that extremely low interest rates, and the Fed's pledge to keep them down for a couple of years to come, justify permanently high prices for stocks. "The mantra for 2020 was that engineered low interest rates can prevent a decline in asset prices. Forever!" he observes. But low rates and super-loose money didn't prevent stocks from cratering in 2000, he notes.

I agree with Grantham's view that low rates don't guarantee high valuations. "Real" rates, adjusted for inflation, reflect demand for capital, and they tend to track economic growth. The faster the economy is waxing, the more profitable new investments become, and the more companies compete for the capital needed to fund those investments. That competition drives up rates. If rates may remain low for a long time, it probably means demand for capital is weak because companies, and hence the economy, are running in place instead of briskly expanding. So low rates generally mean low growth and low profits. And the bulls are banking years and years of fast-rising earnings for today's ultra-pricey sprinters to grow into their gigantic market caps. They're predicting a future of both ultralow rates and ultrahigh profit growth that's never reigned in the past.

History doesn't support the "low rates as rocket fuel" view. Rob Arnott, chief of Research Affiliates, the firm that oversees investment strategies for $145 billion in ETFs and mutual funds, points out that in the 1950s, the 10-year Treasury yielded 1.0% to 1.5%, yet multiples were less than one-third of today's levels. Grantham also observes that Yale economist Robert Shiller, who called the housing collapse of 2009 and tech bubble of 2000, now says that although multiples, using an average of 10 years of earnings, are even higher than in 1929 and 2007, today's lofty prices may be somewhat justified. The reason: The spread between the probable return on stocks and what you can get from bonds is better than in either of those two periods. Both Grantham and Arnott reject the view "stocks are still good ’cause they're so much better than bonds." "What Shiller's really saying is that bonds are terrible, and stocks are slightly less terrible," says Arnott. Grantham agrees: "Bonds are even more spectacularly expensive by historical comparison than stocks. Oh my!"

Grantham acknowledges that it's impossible to call a top. Indeed, he often fled overpriced markets well before the peak. But he strongly implies, as he puts it, that the music will stop, and the dance end, fairly soon. He cites two reasons: the intensifying of enthusiasm for the bulls, and the acceleration in prices that marks a mania's death throes. Grantham says that investors who've been sitting out since the summer of 2020, and missed the big run-up, made the right decision, implying they'll be able to buy shares a lot cheaper in the aftermath of the coming catastrophe. Those are words the bulls will hate. But getting out when things were getting crazy proved a winning strategy for Grantham, and Icahn, for decades. Then they'll do what has always made them successful—feast on the bargains when investors panic and prices go irrationally, crazily low. That's the kind of craziness these legends crave.